Finnish heraldry

Finnish heraldry has a common past with Swedish heraldry until 1809 and it belongs to German heraldric tradition.

Official Heraldry

Arms of the historical provinces of Finland originated in the early Vasa era. Arms of the Grand Duchy of Finland were created in 1581.

Between 1950 and 1970, heraldry in Finland enjoyed an unprecedented increase in popularity. Within a brief period, coats of arms were assigned to all Finnish municipalities. Arms were designed to high standards. Notable heraldists (heraldric designers) included Gustaf von Numers, Ahti Hammar, and Olof Eriksson; the Danish heraldist Sven Tito Achen esteemed them the best in the world at the time.

Samples

-

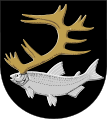

Inari, arms combines local fauna, reindeer and Common whitefish

-

Tervo, arms describing timber floating

-

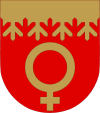

Kerava, refers to furniture industry

-

Kihniö, municipality dominated by sawmills

-

Pielavesi, charges are birch bark horns

-

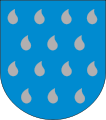

Sumiainen, canting arms, Sumiainen meaning "foggy"

Private Heraldry

The oldest known coat of arms in Finland is in the seal of Bertold, vouti (sheriff) of Häme Castle (1297).

The coats of arms of the Finnish nobility are recorded by the Finnish House of Nobility. The last ennoblement was 1912. Coronets of rank are the same as in Swedish heraldry.

After the renaissance of municipal heraldry, burgher arms also became popular. Burgher arms were used in Finland in the 17th and 18th centuries by wealthy merchants, priests, officers and magistrates, but in many cases by one generation only and they became rare after a royal statute against “use of ‘noble shield and open helmet’ by burghers, 1762”. In fact, non-noble family heraldry does not have roots in Finland, but in Finnish nonheraldic housemarks and in the tradition of burgher arms in Continental Europe. The Heraldic Society of Finland began to keep an unofficial register of burgher arms, which was published in 2006 as an armorial, containing 1356 arms. The Swedish edict against “use of ‘noble shield and open helmet’ by burghers" is still respected and The Heraldic Society of Finland does take in its register burgher arms only with tilting helmet. Each President of Finland needs a coat of arms as a member of Order of the Seraphim in Sweden and for Order of the Elephant in Denmark.

Private flying heraldry is common in Finland and is employed more often than shields or achievements. The use of Household pennants at detached homes and summer houses is common. Private associations often have their own heraldic banners. Table-top pennants of associations are highly valued and often given only to commendable members and affiliates. Even though some of these symbols are fine examples of Finnish heraldry, in spite of clear ambition, many designs lack in heraldic merit.

Finnish heraldry is a very vivid interest amongst the practitioners of historical re-enactment, LARP and living history.

Characteristics

Finnish heraldry is generally quite high quality, which can be seen from the "Ten Commandments for a Designer of Finnish Heraldry", drawn up by Jukka Suvisaari and amended by a committee set up by the Heraldic Society of Finland in April 1990. The committee consisted of Kimmo Kara, Juhani Vepsäläinen and Jukka Suvisaari.

- Only heraldic tinctures are used. These are the metals, gold (Or) and silver (Argent); and the colors, red (Gules), blue (Azure), black (Sable) and green (Vert). In heraldic drawings yellow can be used in place of gold and white in place of silver. In flags and pennants this is almost always done nowadays. Heraldic colours are bright and clean; tones of the colours are picked from center of the scale.

- The use of only two tinctures, of which one is a metal, is preferred. The use of a third tincture requires good reasons, but a fourth is definitely bad heraldry.

- According to the tincture rule, one must not place colour on or next to colour or metal on or next to metal, unless the line of contact is very short.

- Letters, numbers or texts do not belong on a heraldic emblem.

- Figures (charges) must be as big as possible and fill the space intended for them as completely as possible.

- In figures natural presentation is not important, but characteristic is (e.g. the ferocity of the lion, majesty of the eagle, gracefulness of the deer).

- In principle the charges should be two dimensional. At a minimum they must be recognisable even when presented as coloured flat surfaces, without shading or extra borderlines.

- A heraldic emblem must be easy to remember. It should not be crowded with too many symbols, only the essential. The ideal is only one charge.

- It is forbidden to be repetitive in heraldry: one idea should not be symbolized with two or more charges. On the other hand, if one charge suffices to symbolize two or more ideas, it only strengthens the symbolism of the charge, and therefore the whole emblem.

- The charges and the whole emblem must be such that they can be redrawn according to a written description (blazon) of the coat of arms or flag without a model. This means that the charge must be a general presentation of its kind. For example, a castle cannot be a specific castle, but only a stylized heraldic castle (although it can be explained as referring to, say, Korela Fortress). In other words, the description of the charge should not require the use of a proper noun.[1]

Finnish heraldry has introduced some new lines of partition, such as "Fir twig partition" (havukoro) and "Fir tree top partition" (kuusikoro). For example the arms of Outokumpu, designed by Olof Eriksson in 1953, has a fir-twigged chief. Finnish heraldry has also had some influence on South African heraldry.

Vocabulary

| Tincture | Heraldic name | Finnish name |

|---|---|---|

| Metals | ||

| Gold/Yellow | Or | kulta/keltainen |

| Silver/White | Argent | hopea/valkoinen |

| Colours | ||

| Blue | Azure | sininen |

| Red | Gules | punainen |

| Black | Sable | musta |

| Green | Vert | vihreä |

- Heraldry = Heraldiikka

- Coat of arms = Vaakuna

- Coat of arms of a noble family = Aatelisvaakuna

- Burgher arms = Porvarisvaakuna

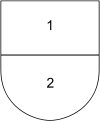

| Example |  |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

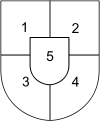

| English name | Parted per fess | Parted per pale | Parted per bend sinister | Parted quarterly | Parted quarterly with a heart |

| Finnish name | katkoinen | halkoinen | vastalohkoinen | nelijakoinen | nelijakoinen ja sydänkilpi |

See also

References

- ↑ Suvisaari, Kruunattu hevosenkenkä Hästsko med krona, 2005. pages 21-23.

- Sven Tito Achen: The Modern Civic Heraldry of Finland – The World’s Best. Report of The XVIth International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Helsinki 16–21 August 1984, Edited by Tom C. Bergroth. Printed by Gummerus Oy 1986. ISBN 951-99640-4-5

- Bo Tennberg: The Renaissance of Heraldry in Finland. Report of The XVIth International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Helsinki 16–21 August 1984, Edited by Tom C. Bergroth. Printed by Gummerus Oy 1986. ISBN 951-99640-4-5

External links

- Municipal coats of arms of Finland (Finnish)

- Heraldic Society of Finland (Finnish)

- Finnish nobility arms (Swedish) at the House of Nobility