First Marx cabinet

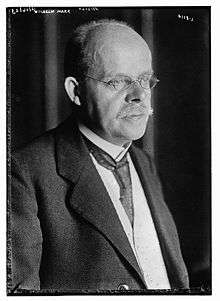

The First Marx cabinet (German: Erstes Kabinett Marx) was the tenth democratically elected Reichsregierung of the German Reich, during the period in which it is now usually referred to as the Weimar Republic. The cabinet was named after Reichskanzler (chancellor) Wilhelm Marx and took office on 30 November 1923 when it replaced the Second Stresemann cabinet which had resigned on 23 November. Marx' first cabinet resigned on 26 May 1924 and was replaced on 3 June by another cabinet under his chancellorship.

Establishment

After the second cabinet of Gustav Stresemann had resigned on 23 November 1923, the situation of the Reich was too critical to be dealt with for long by a mere caretaker government: the Occupation of the Ruhr, a military state of ermergency (in place since 26 September 1923), implementation of the currency reform and the dire state of the public finances. Nevertheless, attempts to create a new coalition turned out to be difficult. A restoration of the "Grand Coalition" including the Social Democrats seemed hopeless. The focus was thus on a new "bourgeois" cabinet based on Zentrum, DVP, DDP and possibly DNVP. Although among the coalition parties the DVP was most amenable to inclusion of the DNVP, the other two parties also tacked to the right in these discussions.[1]

Initially, the Zentrum (including Marx personally) refused to nominate a chancellor and to take the lead in coalition negotiations. Siegfried von Kardorff of the DVP was recommended by DDP and Zentrum on 24 November. Kardoff contacted the DNVP but was rebuffed. Stresemann then suggested to president Friedrich Ebert to hand the task to form a cabinet to the DNVP, but their political demands were unacceptable to Ebert. On 25 November, the president asked Heinrich Albert to form an independent cabinet, but this was vetoed by the parties. A possible chancellorship for Karl Jarres (DVP) was dropped due to opposition from Zentrum and DDP.[1]

The next attempt was made under Adam Stegerwald of the Zentrum and on 27 November negotiations with the DNVP started. Although the right-wing DNVP was ready for some concessions, they demanded that ministers from their party must be included not just in the Reich cabinet but also in the Prussian government. However, the other parties refused to end their coalition with the SPD in Prussia as would have been necessary to make that possible.[1]

Stegerwald gave up on 29 November and asked Ebert to find a less controversial person for the job than himself. This was Wilhelm Marx, chairman of the Zentrum, who by the next day had managed to put together a DVP, DDP and Zentrum coalition. The Bavarian People's Party (BVP) sent one of their Reichstag delegates, Erich Emminger, to serve as Minister of Justice, but as an independent minister, "without party affiliation". No formal coalition agreement was taken.[1]

The new cabinet showed much continuity with the previous one. Zentrum, DVP and DDP agreed that Stresemann should keep the foreign portfolio which he had already held as chancellor. Jarres remained at Interior and also became Vice-Chancellor. Hans Luther, one of the architects of the currency reform, stayed on as Minister of Finance. Otto Gessler and Heinrich Brauns had held their posts since 1920. Rudolf Oeser and Anton Höfle stayed on, with the latter also taking over the Ministry for the Occupied Territories, recently created under Stresemann. Gerhard Graf von Kanitz, a former DNVP member, also remained in the cabinet after Georg Schiele (DNVP) had refused the position at Agriculture. The only new ministers were Eduard Hamm, a former Bavarian Minister of Trade and Staatssekretär at the Reich chancellery of Wilhelm Cuno and Emminger of the BVP. The latter appointment was intended to build a bridge to the Bavarian state government, at the time in more or less open rebellion against the Berlin government.[1]

Overview of the members

The members of the cabinet were as follows:[2]

| First Marx cabinet 30 November 1923 to 26 May/3 June 1924 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reichskanzler | Wilhelm Marx | Zentrum |

| Reichsministerium des Innern (Interior) and Vice-Chancellor |

Karl Jarres | DVP |

| Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) | Gustav Stresemann | DVP |

| Reichsministerium der Finanzen (Finance) | Hans Luther | independent |

| Reichsministerium für Wirtschaft (Economic Affairs) | Eduard Hamm | DDP |

| Reichsministerium für Arbeit (Labour) | Heinrich Brauns | Zentrum |

| Reichsministerium der Justiz (Justice) | Erich Emminger (through 15 April 1924) | BVP |

| Reichswehrministerium (Defence) | Otto Gessler | DDP |

| Reichsministerium für das Postwesen (Mail) and Reichsministerium für die besetzten Gebiete (Occupied Territories) |

Anton Höfle | Zentrum |

| Reichsministerium für Verkehr (Transport) | Rudolf Oeser | DDP |

| Reichsministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (Food and Agriculture) | Gerhard Graf von Kanitz | independent |

Notes: Emminger left office on 15 April 1924. At that point his Staatssekretär (secretary of state), Curt Joël, became acting head of the ministry. The Reichsministerium für Wiederaufbau (reconstruction) was dissolved on 11 May 1924. Previously, it had been led by secretary of state Gustav Müller.[3]

Achievements

Economic policy

The Ermächtigungsgesetz (enabling act) of 8 December 1923 gave the cabinet wide-ranging powers. This made it possible for Marx to implement the currency reform prepared under Stresemann's chancellorship. It required massive adjustments to the public fiscal balance. Earlier large deficits financed by printing money had been a major cause of hyperinflation. Among the measures introduced by the cabinet were a 25% cut in the number of civil servants and various significant tax hikes. With the help of these unpopular decrees, the Marx government achieved the "Miracle of the Rentenmark" of stabilizing the currency.[4]

Domestic security

Marx followed a cautious course in dealing with rebellious state governments. He secretly met Eugen von Knilling, Minister President of Bavaria, on 18 January 1924 and convinced him to drop Gustav von Kahr and Otto von Lossow, two key figures in the right-wing movement in the state. Knilling also agreed to disband the illegal Volksgerichte ("people's courts") and to give up control of the railway (to be reorganised as Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft). In compensation, Marx ordered the high command of the Reichswehr to appoint and dismiss the Landeskommandant for Bavaria in agreement with the state government.[4]

In the west, Marx helped to defuse the situation by promising additional Reich subsidies to the occupied territories on 6 December 1923. Improving economic circumstances soon boosted industrial output and resulted in falling unemployment in that region.[4]

Thus, maintaining the Einheit der Nation (inegritity of the nation) as expressed in the government statement of 4 December 1923, by dealing with Bavaria, the occupied territories and the left-wing uprisings in Thuringia and Saxony was the second main achievement of the first Marx cabinet.[4]

Resignation

On 15 February 1924, the enabling act lapsed and there was no prospect of the Reichstag granting an extension. The parliament met on 20 February and several draft laws were tabled, aimed at undoing some of the government's decrees, notably on taxes, working hours and cuts to the public workforce. The government decided to fight to keep these in place as it saw them as corner stones of its economic and fiscal policies. The opposition parties refused to withdraw their motions. Marx thus asked for the Reichstag to be dissolved on 13 March, arguing that "vital" decrees would otherwise be revoked. The elections of 4 May weakened the parties of the political center and strengthened the extremes of the spectrum. DDP and DVP in particular lost votes. The DNVP (in conjunction with the Landbund) now had the largest parliamentary group and demanded to be included in the government in a leading role.[5]

Since the implementation of the Dawes Plan required a government able to act with decision, the cabinet tried to stay on as caretaker until the new Reichstag assembled. This resulted in criticism both from the DNVP, which called for the cabinet's resignation on 15 May, and from within the coalition parties. Coalition talks started on 21 May, but the DNVP refused to agree to the Dawes Plan (which they had labelled a "second Versailles" during the election campaign). Moreover, their preferred candidate for the chancellorship, Alfred von Tirpitz proved very controversial.[5]

On 26 May, the DVP forced the cabinet to resign. Ebert asked Marx to form a new government. The DNVP demanded a change in foreign policy, the dismissal of Stresemann as foreign minister and a firm pledge regarding a reshuffling of the Prussian government. On 3 June, Marx broke off the negotiations and that same day all the ministers were confirmed in their posts. The BVP was not a part of the new coalition. Zentrum, DDP and DVP thus formed the coalition on which the second Marx cabinet was based.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Die Bildung des ersten Kabinetts Marx (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ "Kabinette von 1919 bis 1933 (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ "Die Kabinette Marx I und II (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Biografie Wilhelm Marx (German)". Bayerische Nationalbibliothek. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Innenpolitische Entwicklung vom ersten zum zweiten Kabinett Marx (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 15 July 2015.