Five Races Under One Union

| Five Races Under One Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The center flag is the Five-Colored Flag of the Republic of China. Underneath the three flags is the message: "Long live the union" (共和萬歲) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 五族共和 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | five races (ethnic groups) living together in mutual harmony | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Five races under one union was one of the major principles upon which the Republic of China was founded in 1911 at the time of the Xinhai Revolution.[1][2][3][4]

.svg.png) | |

| Name | Five-coloured flag (五色旗) |

|---|---|

| Use |

Civil and state flag |

| Proportion | 5:8 |

| Adopted | January 10, 1912 |

| Design | Five horizontal bands of red, yellow, blue, white and black. |

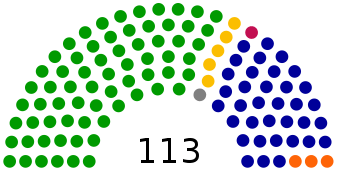

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

| Commonly known as Taiwan |

|

Leadership |

|

|

|

Other branches

|

|

Related topics |

|

Taiwan portal |

Description

This principle emphasized the harmony of the five major ethnic groups in China as represented by the colored stripes of the Five-Colored Flag of the Republic: the Han (red); the Manchus (yellow); the Mongols (blue); the "Hui" (Muslim Chinese) (white); and the Tibetans (black).[5]

The term "Muslim" in this context (including the term 回, huí, in Chinese) primarily referred to the Muslim Turkic peoples in Western China, since the term "Muslim Territory" (回疆; "Huijiang") was an older name for Xinjiang during the Qing dynasty.[6] The meaning of the term "Hui people" gradually shifted to its current sense—a group distinguished from the Han Chinese by little other than their Muslim faith and distant foreign ancestry during the period of roughly 1911–49 in the Republic of China.

History

During the Sui Dynasty, there were historical records of a system of military banners using the colors red (fire), blue (wood), yellow (earth), white (metal), and black (water) representing the five elements. Tang Dynasty inherited this system, and has arranged the colors in a united flag according to the above order of elements for military use.[7] In subsequent historical periods, this "flag of the five united elements" were altered and readapted for military or official uses. In the Qing Dynasty painting which records the Manchu victory over the Muslim Du Wenxiu rebellion in Yunnan, a Qing military flag with the five elements arranged in the order of yellow, white, black, green and red can be seen.[8]

After the Wuchang Uprising, the Qing dynasty made the transition to the Republic of China. There were a number of competing flags that could have been used by the revolutionaries. The military units of Wuchang wanted the 9-star flag with Taijitu.[5] Sun Yat-sen preferred the Blue Sky and White Sun flag to honor Lu Haodong.[5]

Despite the general target of the uprisings to be the Manchus, Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren and Huang Xing unanimously advocated racial integration to be carried out on the frontiers; hence the different colors used for the flag.[9] The general idea is that all of the non-Han races were Chinese also, despite the non-Han portion making up a relatively small percentage of the population.[10]

The "five ethnic groups under one union" flag was no longer used after the Northern Expedition.

A variation of this flag was adopted by Yuan Shikai's empire and the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (Flag of Manchukuo). In Manchukuo, similar slogan (五族協和) was used, but the five races are changed into Japanese (red), Han Chinese (blue), Mongols (white), Koreans (black) and Manchus (yellow).

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the flag was used by several Japanese puppet governments, including the Provisional Government of the Republic of China in the northern part of the country and the Reformed Government of the Republic of China in the central regions.

Gallery

-

Military insignia based on the flag

-

Air force roundel

-

.svg.png)

National flag 1912–1928

-

National flag of Empire of China 1916

-

National flag of Empire of China 1916

-

National flag of Manchukuo 1932–1945

-

Flag of the Reformed Government of the Republic of China (1938–1940)

See also

References

- ↑ Murray A. Rubinstein (1994). Murray A. Rubinstein, ed. The Other Taiwan: 1945 to the present (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 416. ISBN 1-56324-193-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-231-13924-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Paul Hibbert Clyde, Burton F. Beers (1971). The Far East: a history of the Western impact and the Eastern response (1830–1970) (5, illustrated ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 409. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Making of America Project (1949). Harper's magazine, Volume 198. Harper's Magazine Co. p. 104. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- 1 2 3 Fitzgerald, John. [1998] (1998). Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution. Stanford University Press publishing. ISBN 0-8047-3337-6, ISBN 978-0-8047-3337-3. pg 180.

- ↑ Suisheng Zhao (2004). A nation-state by construction: dynamics of modern Chinese nationalism (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-8047-5001-7. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ↑ http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_624ff32c0101ency.html

- ↑ http://5039.bokee.com/991761.html

- ↑ Hsiao-ting Lin. [2010] (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Taylor & Francis publishing. ISBN 0-415-58264-4, ISBN 978-0-415-58264-3. pg 7.

- ↑ Chow, Peter C. Y. [2008] (2008). The "one China" dilemma. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 1-4039-8394-1, ISBN 978-1-4039-8394-7. pg 31.