Five Dynasties

| Five Dynasties | |||||||

| |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 五代 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 五代 | ||||||

| |||||||

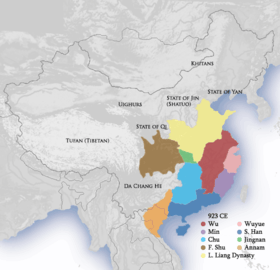

The Five Dynasties was an era of political upheaval in 10th-century China. Five states succeeded one another in the Central Plain. More than a dozen states, referred to as the Ten Kingdoms, were established elsewhere, mainly in south China.

The Later Liang, the first of the five dynasties, was established upon the fall of the Tang dynasty in 907. The era ended with the founding of the Song dynasty in 960. Many states were had military governors who were effectively independent long before 907. The Northern Han survived until 979. Poetry and wood-block printing flowered in this period. The block printing edition of Five Classics were published by Feng Dao, the Chinese Gutenberg. The canal and dam system of northern China fell into disrepair, leading to extensive flooding and famine.

Background

Towards the end of the Tang, the growing threat of barbarian incursions led the imperial government to delegate more authority to regional military governors. The Huang Chao peasant uprising (881-884) massacred many members of the gentry class and forced others to ally with the Turks, weakening the central government. The revival of the money economy increased commerce and prosperity, but strained traditional feudal ties. By the early 10th century, many governors exercised de facto independence. Several governorships evolved into the Ten Kingdoms.

The name "Five Dynasties" was coined by Song dynasty historians and reflects the view that the successive regimes based in Kaifeng possessed the Mandate of Heaven. Yet three of these dynasties were founded by barbarian Turks, and South generally had more stable and effective government in this period.[1]

The states

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | |||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BCE | |||||||

| Xia dynasty c. 2070 – c. 1600 BCE | |||||||

| Shang dynasty c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE | |||||||

| Zhou dynasty c. 1046 – 256 BCE | |||||||

| Western Zhou | |||||||

| Eastern Zhou | |||||||

| Spring and Autumn | |||||||

| Warring States | |||||||

| IMPERIAL | |||||||

| Qin dynasty 221–206 BCE | |||||||

| Han dynasty 206 BCE – 220 CE | |||||||

| Western Han | |||||||

| Xin dynasty | |||||||

| Eastern Han | |||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | |||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | |||||||

| Jin dynasty 265–420 | |||||||

| Western Jin | |||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | ||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | |||||||

| Sui dynasty 581–618 | |||||||

| Tang dynasty 618–907 | |||||||

| (Second Zhou dynasty 690–705) | |||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–960 |

Liao dynasty 907–1125 | ||||||

| Song dynasty 960–1279 |

|||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | ||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | ||||||

| Yuan dynasty 1271–1368 | |||||||

| Ming dynasty 1368–1644 | |||||||

| Qing dynasty 1644–1911 | |||||||

| MODERN | |||||||

| Republic of China 1912–1949 | |||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present |

Republic of China (Taiwan) 1949–present | ||||||

The Five Dynasties were:

- Later Liang (June 1, 907–23)

- Later Tang (923–36)

- Later Jin (936–47)

- Later Han (947–51 or 979, depending on whether Northern Han is considered part of the dynasty)

- Later Zhou (951–60).

Later Liang

During the Liang dynasty, the warlord Zhu Wen held the most power in northern China. Although he was originally a member of Huang Chao's rebel army, he took on a crucial role in suppressing the Huang Chao Rebellion. For this function, he was awarded the Xuanwu Jiedushi title. Within a few years, he had consolidated his power by destroying neighbours and forcing the move of the imperial capital to Luoyang, which was within his region of influence. In 904, he executed Emperor Zhaozong of Tang and made his 13-year-old son a subordinate ruler. Three years later, he induced the boy emperor to abdicate in his favour. He then proclaimed himself emperor, thus beginning the Later Liang.

Later Tang

During the Tang Dynasty, rival warlords declared independence in their governing provinces—not all of whom recognized the emperor's authority. Li Cunxu and Liu Shouguang (劉守光) fiercely fought the regime forces to conquer northern China; Li Cunxu succeeded. He defeated Liu Shouguang (who had proclaimed a Yan Empire in 911) in 915, and declared himself emperor in 923; within a few months, he brought down the Later Liang regime. Thus began the Later Tang—the first in a long line of conquest dynasties. After reuniting much of northern China, Cunxu conquered Former Shu in 925, a regime that had been set up in Sichuan.

Later Jin

The Later Tang had a few years of relative calm, followed by unrest. In 934, Sichuan again asserted independence. In 936, Shi Jingtang, a Shatuo jiedushi from Taiyuan, was aided by the Liao dynasty in a rebellion against the dynasty. In return for their aid, Shi Jingtang promised annual tribute and the Sixteen Prefectures (modern northern Hebei and Beijing) to the Khitans. The rebellion succeeded; Shi Jingtang became emperor in this same year.

Not long after the founding of the Later Jin, the Khitans regarded the emperor as a proxy ruler for China proper. In 943, the Khitans declared war and within three years seized the capital, Kaifeng, marking the end of Later Jin. But while they had conquered vast regions of China, the Khitans were unable or unwilling to control those regions and retreated from them early in the next year.

Later Han

To fill the power vacuum, the jiedushi Liu Zhiyuan entered the imperial capital in 947 and proclaimed the advent of the Later Han, establishing a third successive Shatuo reign. This was the shortest of the five dynasties. Following a coup in 951, General Guo Wei, a Han Chinese, was enthroned, thus beginning the Later Zhou. However, Liu Chong, a member of the Later Han imperial family, established a rival Northern Han regime in Taiyuan and requested Khitan aid to defeat the Later Zhou.

Later Zhou

After the death of Guo Wei in 951, his adopted son Chai Rong succeeded the throne and began a policy of expansion and reunification. In 954, his army defeated combined Khitan and Northern Han forces, ending their ambition of toppling the Later Zhou. Between 956 and 958, forces of Later Zhou conquered much of Southern Tang, the most powerful regime in southern China, which ceded all the territory north of the Yangtze in defeat. In 959, Chai Rong attacked the Liao in an attempt to recover territories ceded during the Later Jin. After many victories, he succumbed to illness.

In 960, the general Zhao Kuangyin staged a coup and took the throne for himself, founding the Northern Song Dynasty. This is the official end of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. During the next two decades, Zhao Kuangyin and his successor Zhao Kuangyi defeated the other remaining regimes in China proper, conquering Northern Han in 979, and reunifying China completely in 982.

Northern Han

Though considered one of the ten kingdoms, the Northern Han was based in the traditional Shatuo stronghold of Shanxi. It was created after the last of three dynasties created by Shatuo Turks fell to the Han-governed Later Zhou in 951. With the protection of the powerful Liao, the Northern Han maintained nominal independence until the Song Dynasty wrested it from the Khitan in 979.

Law

In later tradition, the Five Dynasties is viewed as a period of judicial abuse and excessive punishment. This view reflects both actual problems with the administration of justice and the bias of Confucian historians, who disapproved of the decentralization and militarization that characterized this period. While Tang procedure called for the delaying executions until appeals were exhausted, this was not generally the case in the Five Dynasties.[2]

Other abuses included the use of severe torture. The Later Han was the most notorious dynasty in this regard. Suspects could be tortured to death with long knives and nails. The military officer in charge of security of the capital is said to have executed suspects without inquiry.[2]

The Tang code of 737 was the basic statutory law for this period, together supplemental edicts and collections.[2] The Later Liang promulgated a code in 909.[2] This code was blamed for delays in the administration of justice and said to be excessively harsh with respect to economic crimes. The Later Tang, Later Jin, and Later Zhou also produced recompilations. The Later Han was in power too briefly to make a mark on the legal system[2]

See also

- Annam (Chinese province)

- Family trees of the emperors of the Five Dynasties

- Chinese sovereign

- Liao dynasty

- Conquest of Southern Tang by Song

- Zizhi Tongjian

Further reading

- Dudbridge, Glen (2013). A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880-956). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199670680.

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011). China's Southern Tang Dynasty (937-976). Routledge. ISBN -9780415454964.

- Lorge, Peter, ed. (2011). Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. The Chinese University Press. ISBN 962996418X.

- Ouyang Xiu (2004) [1077]. Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. (transl. Richard L. Davis). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12826-6.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1954). Empire of Min: A South China Kingdom of the Tenth Century. Tuttle Publishing.

- Wang Gungwu (1963). The Structure of Power in North China During the Five Dynasties. Stanford University Press.

- Wang Hongjie (2011). Power and Politics in Tenth-Century China: The Former Shu Regime. Cambria Press. ISBN 1604977647.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. |

| Preceded by Tang dynasty |

Dynasties in Chinese history 907–960 |

Succeeded by Song dynasty Liao dynasty |

References

- ↑ Eberhard, Wolfram, A History of China (1977), "Chapter IX: The Epoch of the Second Division of China."

- 1 2 3 4 5 John W. Chaffee, Denis Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China: Volume 5, The Five Dynasties and Sung China, 960–1279 AD, Part 2, Cambridge University Press, 5 Mar 2015, McKnight, Brian, "Chapter 4: Chinese law and the legal system"