Fort Le Boeuf

| Fort Le Boeuf | |

|---|---|

| Waterford, Pennsylvania, USA | |

|

Fort Le Boeuf in 1754 | |

| Coordinates | 41°56′22″N 79°58′57″W / 41.939510°N 79.982452°W |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by |

|

| Site history | |

| Built | 1753 |

| In use | 1753–1763 |

| Demolished | 1763-06-18 |

| Battles/wars |

French and Indian War Pontiac's Rebellion |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre |

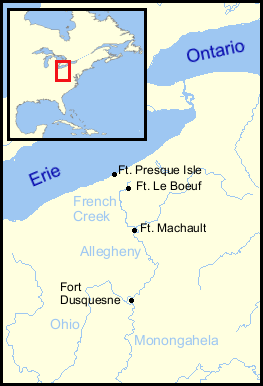

Fort Le Boeuf, (often referred to as Fort de la Rivière au Bœuf), was a fort established by the French in 1753 on a fork of French Creek, in present-day Waterford, in northwest Pennsylvania. The fort was part of a line that included Fort Presque Isle, Fort Machault, and Fort Duquesne.

The fort was located about 15 miles (24 km) from the shores of Lake Erie, on the banks of LeBoeuf Creek, which the fort was named for. The French portaged trade goods, materiel, and supplies from Lake Erie overland to Fort Le Boeuf. From there they traveled by raft and canoe down French Creek to the Allegheny River, the Ohio and the Mississippi.

History

Captain Francois Le Mercier began construction on 11 July 1753; Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre took command of the fort on 3 December 1753. This fort was the second in a series of posts that the French built between spring 1753 and summer 1754 to assert their possession of the Ohio Country. These four posts Fort Presque Isle, Fort LeBoeuf, Fort Machault, and Fort Duquesne ran from Lake Erie to the Forks of the Ohio; they represented the last links in France's effort to connect its dominions in Canada with those in the Illinois Country and Louisiana. The English trading post of John Frazier, at Venango at the junction of French Creek and the Allegheny River (where Franklin is now located) was seized and occupied. Leaving a force to garrison the new posts, the French command returned to Canada for the winter.[1]

Fort LeBoeuf (modern Waterford, Pennsylvania) guarded the southern end of the portage road between Lake Erie and French Creek, which ran to the Allegheny River. It served as a French trading post and garrison until 1759, when the fall of Fort Niagara forced the French to abandon the Ohio Country.[2]

Washington's mission

Robert Dinwiddie, the governor of Virginia, sent the 21-year-old George Washington to Fort Le Boeuf with seven escorts, in order to deliver a message to the French demanding that they leave the Ohio Country. Dinwiddie's initiative was in response to the French building forts in the Ohio Country. Washington took Christopher Gist along as his guide; during the trip, Gist earned his place in history by saving the young Washington's life on two separate occasions. Washington and Gist arrived at Fort Le Boeuf on 11 December 1753. Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, commandant at Fort Le Boeuf, a tough veteran of the west, received Washington politely, but contemptuously rejected his blustering ultimatum.[3]

Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre gave Washington three days hospitality at the fort, and then gave Washington a letter for him to deliver to Dinwiddie. The letter ordered the Governor of Virginia to deliver his demand to the Major General of New France in the capital, Quebec City.[4]

During his stay, Washington noted that the fort had one hundred men, a large number of officers, 50 birch canoes and 70 pine canoes, many unfinished. He described the fort as on a south or west fork of French creek, near the water, and almost surrounded by it. Four houses composed the sides. The bastions were made of piles driven into the ground, standing more than 12 feet (3.7 m) high, and sharpened at the top. Port holes for cannon and loop-holes for small-arms were cut into the bastions. Each bastion mounted eight six-pound cannon and one four-pound cannon guarded the gate. Inside the bastions stood a guard-house, chapel, doctor's lodging and the commander's private stores. Outside the fort were several log barracks, some covered with bark, others with boards. In addition, there were stables, a smithy and other buildings.

War

The French and Indian War began on 28 May 1754 with the Battle of Great Meadows. Some four years later, on 25 July 1759, the French surrendered Fort Niagara. In August 1759, the commander of Fort Presque Isle sent word to Fort Machault and Fort Le Boeuf to abandon their positions. After the French had complied, the British took possession of their sites. It is unclear whether the French burned down Fort Le Boeuf when they abandoned it. If so, the British rebuilt it.

During Pontiac's Rebellion, on 18 June 1763, a war party of Native Americans burned down Fort Le Boeuf. The survivors escaped to Fort Venango, but it too was burned, so they continued to Fort Pitt.

On 1 August 1794, Major Ebenezer Denny reported to Governor Thomas Mifflin from Le Boeuf. He described a fortification with four blockhouses, manned by riflemen. The two rear blockhouses had a six-pound cannon on the second floor, as well as swivel guns over the gates.

When Judge Vincent settled in Waterford in 1797, he wrote, "There are no remains of the old French fort excepting the traces on the ground..."

References

- ↑ National Park Service

- ↑ Fort Le Boeuf Historical Marker

- ↑ "France in America, Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, p. 181

- ↑ Nos racines, l'histoire vivante des Québécois, Éditions Comémorative, Livre-Loisir Ltée. p457

Sources

- "The Journal of Major George Washington, of His Journey to the French Forces on Ohio," George Washington, 1754.

- "The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania," Albert, George Dallas, C. M. Busch, state printer, Harrisburg, 1896. Sketch of the site on pg. 556a shows Fort Le Boeuf at the intersection of Water Street and High Street (present-day Route 97). Caption reads, "Fort Le Boeuf built by the French in 1753 Burned in 1763." Description of fort by Washington, pg. 572. Descriptions of the fort, pgs. 566 - 581.

- Stotz, Charles Morse (2005). Outposts Of The War For Empire: The French And English In Western Pennsylvania: Their Armies, Their Forts, Their People 1749-1764. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-4262-3.