First Indochina War

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

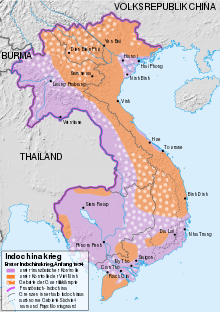

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in contemporary Vietnam) began in French Indochina on 19 December 1946 and lasted until 1 August 1954. Fighting between French forces and their Viet Minh opponents in the South dated from September 1945. The conflict pitted a range of forces, including the French Union's French Far East Expeditionary Corps, led by France and supported by Emperor Bảo Đại's Vietnamese National Army against the Viet Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh and its People's Army of Vietnam led by Vo Nguyen Giap. Most of the fighting took place in Tonkin in Northern Vietnam, although the conflict engulfed the entire country and also extended into the neighboring French Indochina protectorates of Laos and Cambodia.

At the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, the Combined Chiefs of Staff decided that Indochina south of latitude 16° North was to be included in the Southeast Asia Command under British Admiral Mountbatten. Japanese forces located south of that line surrendered to him and those to the north surrendered to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. In September 1945, Chinese forces entered Tonkin and a small British task force landed at Saigon. The Chinese accepted the Vietnamese government under Ho Chi Minh, created by resistance forces of the Viet Minh, then in power in Hanoi. The British refused to do likewise in Saigon, and deferred to the French there from the outset, against the ostensible support of the Viet Minh by American OSS representatives. On V-J Day, September 2, Ho Chi Minh had proclaimed in Hanoi the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). The DRV ruled as the only civil government in all of Vietnam for a period of about 20 days, after the abdication of Emperor Bảo Đại, who had governed under Japanese rule and thus was considered by Vietminh a "Japanese puppet". On 23 September 1945, with the knowledge of the British Commander in Saigon, French forces overthrew the local DRV government, and declared French authority restored in Cochinchina. Guerrilla warfare began around Saigon immediately.[22]

The first few years of the war involved a low-level rural insurgency against French authority. However, after the Chinese communists reached the northern border of Vietnam in 1949, the conflict turned into a conventional war between two armies equipped with modern weapons supplied by the United States and the Soviet Union.[23] French Union forces included colonial troops from the whole former empire (Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities), French professional troops and units of the French Foreign Legion. The use of metropolitan recruits was forbidden by the government to prevent the war from becoming even more unpopular at home. It was called the "dirty war" (la sale guerre) by the Leftist intellectuals in France.[24]

The strategy of pushing the Viet Minh into attacking a well-defended base in a remote part of the country at the end of their logistical trail was validated at the Battle of Nà Sản. However this base was relatively weak by the lack of construction materials like concrete and steel, limited usefulness of armored tanks in a jungle environment, lack of strong air forces for air cover and carpet bombing and use of recruited foreign forces from other French colonies (mainly from Algeria, Morocco and even Vietnam), caused by the unpopularity of this war in France which proscribed the use of regular French recruits. On the other hand, Giap used efficient and novel tactics of direct fire artillery, convoy ambushes and amassed anti-aircraft guns to impede land or air supply deliveries together with a strategy based on recruiting a sizable regular army facilitated by wide popular support, a guerrilla warfare doctrine and instruction developed in China and the use of simple and reliable war material provided by the Soviet Union. This combination proved fatal for this base defenses, culminating in a decisive French defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.[25]

At the International Geneva Conference on July 21, 1954 the new socialist French government and the Viet Minh made an agreement that was denounced by the government of Vietnam and by the United States, but which effectively gave the Communists control of North Vietnam above the 17th parallel. Control of the north was given to the Viet Minh under Ho Chi Minh, and the south continued under Emperor Bảo Đại. A year later, Bảo Đại would be deposed by his prime minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, creating the Republic of Vietnam. Soon an insurgency backed by the North developed against Diệm's government. The conflict gradually escalated into the Vietnam War.

Background

.jpg)

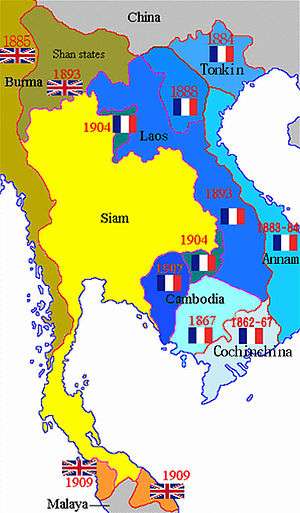

Vietnam was absorbed into French Indochina in stages between 1858 and 1887 with European influence and education. Nationalism grew until World War II provided a break in French control. Early Vietnamese resistance centered on the intellectual Phan Bội Châu. Châu looked to Japan, which had modernized and was one of the few Asian nations to resist European colonization. With Prince Cường Để, Châu started two organizations in Japan, the Duy Tân hội (Modernistic Association) and Vietnam Cong Hien Hoi.

Due to French pressure, Japan deported Phan Bội Châu to China. Witnessing Sun Yat-sen's 1911 nationalist revolution, Châu was inspired to commence the Viet Nam Quang Phục Hội movement in Guangzhou. From 1914 to 1917, he was imprisoned by Yuan Shikai's counterrevolutionary government. In 1925, he was captured by French agents in Shanghai and spirited to Vietnam. Due to his popularity, Châu was spared from execution and placed under house arrest until his death in 1940.

In September 1940, shortly after Phan Bội Châu's death, Japan launched its invasion of French Indochina, mirroring its ally Germany's conquest of metropolitan France. Keeping the French colonial administration, the Japanese ruled from behind the scenes in a parallel of Vichy France. As far as Vietnamese nationalists were concerned, this was a double-puppet government. Emperor Bảo Đại collaborated with the Japanese, just as he had with the French, ensuring his lifestyle could continue.

From October 1940 to May 1941, during the Franco-Thai War, the Vichy French in Indochina were involved with defending their colony in a border conflict which saw the forces of Thailand invade, while the Japanese sat on the sidelines. Thai military successes were limited to the Cambodian border area, and in January 1941 Vichy France's modern naval forces soundly defeated the inferior Thai naval forces in the Battle of Ko Chang. The war ended in May, with the French agreeing to minor territorial revisions which restored formerly Thai areas to Thailand.

In March 1945, Japan launched the Second French Indochina Campaign and ousted the Vichy French and formally installed Emperor Bảo Đại in the short-lived Empire of Vietnam.

Japanese forces surrender (August 1945)

On August 22, 1945, OSS agents Archimedes Patti and Carleton B. Swift Jr. arrived in Hanoi on a mercy mission to liberate allied POWs and were accompanied by Jean Sainteny, a French government official.[26] The Japanese forces informally surrendered (the official surrender was to take place on September 2, 1945, in Tokyo Bay), but being the only force capable of maintaining law and order, the Japanese Imperial Army remained in power while keeping French colonial troops and Sainteny detained.[27]

Japanese forces allowed the Viet Minh and other nationalist groups to take over public buildings and weapons without resistance, which began the August Revolution. After their defeat, the Japanese Army gave weapons to the Viet Minh. In order to further help the nationalists, the Japanese kept Vichy French officials and military officers imprisoned for a month after the surrender. OSS officers met repeatedly with Ho Chi Minh and other Viet Minh officers during this period and on September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared independence from France for Vietnam.[28]

The Viet Minh had recruited more than 600 Japanese soldiers and given them roles to train or command Vietnamese soldiers.[29][30]

In September 1945, Ho Chi Minh claimed in a speech that, due to a combination of ruthless Japanese exploitation and poor weather, a famine occurred in which approximately two million Vietnamese died. The Viet Minh arranged a relief effort in the north and won wide support there as a result.

American President Franklin D. Roosevelt and General Joseph Stilwell privately made it adamantly clear that the French were not to reacquire French Indochina (modern day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) after the war was over. Roosevelt offered Chiang Kai-shek to place all of Indochina under Chinese rule. Chiang Kai-shek supposedly replied: "Under no circumstances!"[31] Roosevelt died shortly thereafter and U.S. resistance to French rule weakened, eventually capitulating to intense pressure from Charles de Gaulle.[32]

In mid-September 1945, 200,000 troops of the Chinese 1st Army arrived in what would become North Vietnam (Indochina above the 16th parallel). They had been sent by Chiang Kai-shek under General Lu Han to accept the surrender of Japanese forces occupying that area which had been designated to Chiang Kai-Shek under Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers "General Order no. One".[33][34] The Chinese forces remained there until 1946[35] and initially kept the French Colonial soldiers interned with the acquiescence of the Americans.[27] The Chinese used the VNQDĐ, the Vietnamese branch of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in Indochina and put pressure on their opponents.[36]

Chiang Kai-shek threatened the French with war in response to manoeuvering by the French and Ho Chi Minh against each other, forcing them to come to a peace agreement, and in February 1946 he also forced the French to surrender all of their concessions in China and renounce their extraterritorial privileges in exchange for withdrawing from northern Indochina and allowing French troops to reoccupy the region starting in March 1946.[37][38][39][40]

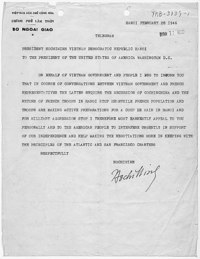

Ho Chi Minh was able to persuade Emperor Bảo Đại to abdicate on August 25, 1945. Bảo Đại was appointed "supreme advisor" to the new Vietminh-led government in Hanoi, which asserted independence on September 2. Deliberately borrowing from the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed on September 2:

"We hold the truth that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among them life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."[41]

With the fall of the short-lived Japanese colony of the Empire of Vietnam, the Provisional Government of the French Republic wanted to restore its colonial rule in French Indochina as the final step of the Liberation of France. An armistice was signed between Japan and the United States on August 20, 1945. CEFEO Expeditionary Corps leader General Leclerc signed the armistice with Japan on board the USS Missouri on behalf of France, on September 2.

On September 13, 1945, a Franco-British task force landed in Java, main island of the Dutch East Indies (for which independence was being sought by Sukarno), and Saigon, capital of Cochinchina (southern part of French Indochina), both being occupied by the Japanese and ruled by Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, Commander-in-Chief of Japan's Southern Expeditionary Army Group based in Saigon.[42] Allied troops in Saigon were an airborne detachment, two British companies of the Indian 20th Infantry Division and the French 5th Colonial Infantry Regiment, with British General Sir Douglas Gracey as supreme commander. The latter proclaimed martial law on September 21. The following night the Franco-British troops took control of Saigon.[43]

Almost immediately afterward, the Chinese Government, as agreed to at the Potsdam Conference, occupied French Indochina as far south as the 16th parallel in order to supervise the disarming and repatriation of the Japanese Army. This effectively ended Ho Chi Minh's nominal government in Hanoi.

On October 9, 1945, General Leclerc arrived in Saigon, accompanied by French Colonel Massu's March Group (Groupement de marche). Leclerc's primary objectives were to restore public order in south Vietnam and to militarize Tonkin (north Vietnam). Secondary objectives were to wait for French backup in view to take back Chinese-occupied Hanoi, then to negotiate with the Viet Minh officials.[43]

Timeline

1946

Fighting broke out in Haiphong after a conflict of interest in import duty at the port between the Viet Minh government and the French.[44] On November 23, 1946, the French fleet began a naval bombardment of the Vietnamese sections of the city that killed over 6,000 Vietnamese civilians in one afternoon.[45][46][47] The Viet Minh quickly agreed to a cease-fire and left the cities. This is known as the Haiphong incident.

There was never any intention among the Vietnamese to give up, as General Võ Nguyên Giáp soon brought up 30,000 men to attack the city. Although the French were outnumbered, their superior weaponry and naval support made any Viet Minh attack unsuccessful. In December, hostilities also broke out in Hanoi between the Viet Minh and the French, and Ho Chi Minh was forced to evacuate the capital in favor of remote mountain areas. Guerrilla warfare ensued, with the French controlling most of the country except far-flung areas.

1947

In 1947, General Võ Nguyên Giáp retreated his command to Tan Trao deep in the hills of Tuyên Quang Province. The French sent military expeditions to attack his bases, but Giap refused to meet them head-on in battle. Wherever the French troops went, the Viet Minh disappeared. Late in the year the French launched Operation Lea to take out the Viet Minh communications center at Bắc Kạn. They failed to capture Ho Chi Minh and his key lieutenants as intended. The French claimed 9,000 Viet Minh soldiers KIA during the campaign which, if true, would represent a major blow for the insurgency.

1948

In 1948, France started looking for means of opposing the Viet Minh politically, with an alternative government in Saigon. They began negotiations with the former emperor Bảo Đại to lead an "autonomous" government within the French Union of nations, the State of Vietnam. Two years before, the French had refused Ho's proposal of a similar status, albeit with some restrictions on French power and the latter's eventual withdrawal from Vietnam.

However, they were willing to give it to Bảo Đại as he had freely collaborated with French rule of Vietnam in the past and was in no position to seriously negotiate or impose demands (Bảo Đại had no military of his own, but soon he would have one).

1949

In 1949, France officially recognized the "independence" of the State of Vietnam as an associated state within the French Union under Bảo Đại. However, France still controlled all foreign relations and every defense issue as Vietnam was only nominally an independent state within the French Union. The Viet Minh quickly denounced the government and stated that they wanted "real independence, not Bảo Đại independence". Later on, as a concession to this new government and a way to increase their numbers, France agreed to the formation of the Vietnamese National Army to be commanded by Vietnamese officers.

These troops were used mostly to garrison quiet sectors so French forces would be available for combat. Private Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo and the Bình Xuyên gangster armies were used in the same way. The Vietnamese Communists in return obtained outside support in 1949 when Chairman Mao Zedong succeeded in taking control of China by defeating the Kuomintang, thus gaining a major political ally and supply area just across the border. In the same year, the French also granted independence (within the framework of the French Union) to the other two nations in Indochina, the Kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia.

The United States began to give military aid to France in the form of weaponry and military observers. Chinese assistance to the Viet Minh began after the communist victory in China. Giap re-organized his local irregular forces into five full conventional infantry divisions, the 304th, 308th, 312th, 316th and the 320th. The war began to intensify when Giap went on the offensive, attacking isolated French bases along the Chinese border.

1950

In February 1950, Giap seized the vulnerable 150-strong French garrison at Lai Khê in Tonkin just south of the border with China. Major general Thái attacked Đông Khê on September 15.[48] Đông Khê fell on September 18, and Cao Bằng finally fell on October 3.

Lạng Sơn, with its 4,000-strong French Foreign Legion garrison, was attacked immediately after. The retreating French on Route 4, together with the relief force coming from That Khe, were attacked all the way by ambushing Viet Minh forces. The French air-dropped a paratroop battalion south of Cao Bằng to act as diversion only to see it quickly surrounded and destroyed. On October 17, Lạng Sơn, after a week of intense fighting, finally fell.

By the time the remains of the garrisons reached the safety of the Red River Delta, 4,800 French troops had been killed, captured or missing in action and 2,000 wounded out of a total garrison force of over 10,000. Also lost were 13 artillery pieces, 125 mortars, 450 trucks, 940 machine guns, 1,200 submachine guns and 8,000 rifles destroyed or captured during the fighting. China and the Soviet Union recognized Ho Chi Minh as the legitimate ruler of Vietnam and sent him more and more supplies and material aid. The year 1950 also marked the first time that napalm was ever used in Vietnam (this type of weapon was supplied by the U.S. for the use of the French Aéronavale at the time).

The military situation improved for France when its new commander, General Jean Marie de Lattre de Tassigny, built a fortified line from Hanoi to the Gulf of Tonkin, across the Red River Delta, to hold the Viet Minh in place and use his troops to smash them against this barricade, which became known as the De Lattre Line. This led to a period of success for the French.

1951

On January 13, 1951, Giáp moved the 308th and 312th Divisions, made up of over 20,000 men, to attack Vĩnh Yên, 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Hanoi, which was manned by the 6,000-strong 9th Foreign Legion Brigade. The Viet Minh entered a trap. Caught for the first time in the open and actually forced to fight the French head-on, without the ability to quickly hide and retreat, they were mown down by concentrated French artillery and machine gun fire. By January 16, the Battle of Vĩnh Yên ended as Giáp was forced to withdraw, with over 6,000 of his troops killed, 8,000 wounded and 500 captured.

On March 23, Giáp tried again, launching an attack against Mạo Khê, 20 miles (32 km) north of Haiphong. The 316th Division, composed of 11,000 men, with the partly rebuilt 308th and 312th Divisions in reserve, went forward and were beaten in bitter hand-to-hand fighting against French troops. Giap, having lost over 3,000 (French estimation) / ~500 (Viet Minh information) dead and wounded by March 28, withdrew.

Giáp launched yet another attack, the Battle of the Day River, on May 29 with the 304th Division at Phủ Lý, the 308th Division at Ninh Bình, and the main attack delivered by the 320th Division at Phat Diem south of Hanoi. The attacks fared no better and the three divisions lost heavily. Taking advantage of this, de Lattre mounted his counteroffensive against the demoralized Viet Minh, driving them back into the jungle and eliminating the enemy pockets in the Red River Delta by June 18, costing the Viet Minh over 10,000 killed.[49]

Every effort by Võ Nguyên Giáp to break the De Lattre Line failed and every attack he made was answered by a French counter-attack that destroyed his forces. Viet Minh casualties rose alarmingly during this period, leading some to question the leadership of the Communist government, even within the party. However, any benefit this may have reaped for France was negated by the increasing domestic opposition to the war in France.

On July 31, French General Charles Chanson was assassinated during a propaganda suicide attack at Sa Đéc in South Vietnam that was blamed on the Viet Minh although it was argued in some quarters that Cao Đài nationalist Trình Minh Thế could have been involved in its planning.

On November 14, 1951, the French seized Hòa Bình, 25 miles (40 km) west of the De Lattre Line, by a parachute drop and extended their perimeter.

1952

In January, General de Lattre fell ill from cancer and had to return to France for treatment. He died there shortly thereafter and was replaced by General Raoul Salan as the overall commander of French forces in Indochina. Viet Minh launched attacks on Hòa Bình, forcing the French to withdraw back to their main positions on the De Lattre line by February 22, 1952. Each side lost nearly 5,000 men in this campaign, and it showed that the war was far from over.

Throughout the war theater, the Viet Minh cut French supply lines and began to seriously wear down the resolve of the French forces. There were continued raids, skirmishes and guerrilla attacks, but through most of the rest of the year each side withdrew to prepare itself for larger operations. Starting on October 2, the Battle of Nà Sản saw the first use of the French commanders’ "hedgehog" tactics consisting in setting up a well-defended outpost to get the Viet Minh out of the jungle and force it to fight a conventional battle instead of ambushes. At first this strategy was successful for the French Union but it ended with a fiasco in 1954.

On October 17, 1952, Giáp launched attacks against the French garrisons along Nghĩa Lộ, northwest of Hanoi, and overran much of the Black River valley, except for the airfield of Nà Sản where a strong French garrison entrenched. Giáp by now had control over most of Tonkin beyond the De Lattre line. Raoul Salan, seeing the situation as critical, launched Operation Lorraine along the Clear River to force Giáp to relieve pressure on the Nghĩa Lộ outposts.

On October 29, 1952, in the largest operation in Indochina to date, 30,000 French Union soldiers moved out from the De Lattre line to attack the Viet Minh supply dumps at Phú Yên. Salan took Phú Thọ on November 5, and Phu Doan on November 9 by a parachute drop, and finally Phú Yên on November 13. Giáp at first did not react to the French offensive. He planned to wait until their supply lines were overextended and then cut them off from the Red River Delta.

Salan correctly guessed what the Viet Minh were up to and cancelled the operation on November 14, beginning to withdraw back to the De Lattre Line. The only major fighting during the operation came during the withdrawal, when the Viet Minh ambushed the French column at Chan Muong on November 17. The road was cleared after a bayonet charge by the Indochinese March Battalion, and the withdrawal could continue. The French lost around 1,200 men during the whole operation, most of them during the Chan Muong ambush. The operation was partially successful, proving that the French could strike out at targets outside the De Lattre Line. However, it failed to divert the Viet Minh offensive or seriously damage its logistical network.

1953

On April 9, 1953, Giáp, after having failed repeatedly in direct attacks on French positions in Vietnam, changed strategy and began to pressure the French by invading Laos, surrounding and defeating several French outposts such as Muong Khoua. In May, General Henri Navarre replaced Salan as supreme commander of French forces in Indochina. He reported to the French government "... that there was no possibility of winning the war in Indo-China," saying that the best the French could hope for was a stalemate.

Navarre, in response to the Viet Minh attacking Laos, concluded that "hedgehog" centers of defense were the best plan. Looking at a map of the area, Navarre chose the small town of Điện Biên Phủ, located about 10 miles (16 km) north of the Lao border and 175 miles (282 km) west of Hanoi as a target to block the Viet Minh from invading Laos. Điện Biên Phủ had a number of advantages: it was on a Viet Minh supply route into Laos on the Nam Yum River, it had an old airstrip for supply, and it was situated in the Tai hills where the Tai tribesmen, still loyal to the French, operated.

Operation Castor was launched on November 20, 1953, with 1,800 men of the French 1st and 2nd Airborne Battalions dropping into the valley of Điện Biên Phủ and sweeping aside the local Viet Minh garrison. The paratroopers gained control of a heart-shaped valley 12 miles (19 km) long and 8 miles (13 km) wide surrounded by heavily wooded hills. Encountering little opposition, the French and Tai units operating from Lai Châu to the north patrolled the hills.

The operation was a tactical success for the French. However, Giáp, seeing the weakness of the French position, started moving most of his forces from the De Lattre line to Điện Biên Phủ. By mid-December, most of the French and Tai patrols in the hills around the town were wiped out by Viet Minh ambushes. The fight for control of this position would be the longest and hardest battle for the French Far East Expeditionary Corps and would be remembered by the veterans as "57 Days of Hell".

1954

By 1954, despite official propaganda presenting the war as a "crusade against communism",[50][51] the war in Indochina was still growing unpopular with the French public. The political stagnation of the Fourth Republic meant that France was unable to extract itself from the conflict. The United States initially sought to remain neutral, viewing the conflict as chiefly a decolonization war.

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu occurred in 1954 between Viet Minh forces under Võ Nguyên Giáp, supported by China and the Soviet Union, and the French Union's French Far East Expeditionary Corps, supported by US financing and Indochinese allies. The battle was fought near the village of Điện Biên Phủ in northern Vietnam and became the last major battle between the French and the Vietnamese in the First Indochina War.

The battle began on March 13 when a preemptive Viet Minh attack surprised the French with heavy artillery. The artillery damaged both the main and secondary airfields that the French were using to fly in supplies. The only road into Điện Biên Phủ, already difficult to traverse, was also knocked out by Viet Minh forces. With French supply lines interrupted, the French position became untenable, particularly when the advent of the monsoon season made dropping supplies and reinforcements by parachute difficult. With defeat imminent, the French sought to hold on until the opening of the Geneva peace meeting on April 26. The last French offensive took place on May 4, but it was ineffective. The Viet Minh then began to hammer the outpost with newly supplied Soviet Katyusha rockets and other weaponry provided by Communist allies.

The final fall took two days, May 6 and 7, during which the French fought on but were eventually overrun by a huge frontal assault. General Cogny, based in Hanoi, ordered General de Castries, who was commanding the outpost, to cease fire at 5:30 pm and to destroy all materiél (weapons, transmissions, etc.) to deny their use to the enemy. A formal order was given to not use the white flag so that the action would be considered a ceasefire instead of a surrender. Much of the fighting ended on May 7; however, the ceasefire was not respected on Isabelle, the isolated southern position, where the battle lasted until May 8, 1:00 am.[52]

At least 2,200 members of the 20,000-strong French forces died, and another 1,729 were reported missing after the battle, and 11,721 were captured. Of the 50,000 or so Vietnamese soldiers thought to be involved, there were an estimated 4,800 to 8,000 killed and another 9,000–15,000 wounded. The prisoners taken at Điện Biên Phủ were the greatest number the Viet Minh had ever captured: one-third of the total captured during the entire war.

One month after Điện Biên Phủ, the composite Groupe Mobile 100 (GM100) of the French Union forces evacuated the An Khê outpost and was ambushed by a larger Viet Minh force at the Battle of Mang Yang Pass from June 24 to July 17. At the same time, Giap launched some offensives against the delta, but they all failed. The Viet Minh victory at Điện Biên Phủ heavily influenced the outcome of the 1954 Geneva accords that took place on July 21. In August Operation Passage to Freedom began, consisting of the evacuation of Catholic and loyalist Vietnamese civilians from communist North Vietnamese persecution.

Ethnic minorities

The French were backed by the Nung minority while Viet Minh were backed by the Tay minority.[53]

Geneva Conference and Partition

Negotiations between France and the Viet Minh started in Geneva in April 1954 at the Geneva Conference, during which time the French Union and the Viet Minh were fighting a battle at Điện Biên Phủ. In France, Pierre Mendès France, opponent of the war since 1950, had been invested as Prime Minister on June 17, 1954, on a promise to put an end to the war, reaching a ceasefire in four months:

"Today it seems we can be reunited in a will for peace that may express the aspirations of our country ... Since already several years, a compromise peace, a peace negotiated with the opponent seemed to me commanded by the facts, while it commanded, in return, to put back in order our finances, the recovery of our economy and its expansion. Because this war placed on our country an unbearable burden. And here appears today a new and formidable threat: if the Indochina conflict is not resolved — and settled very fast — it is the risk of war, of international war and maybe atomic, that we must foresee. It is because I wanted a better peace that I wanted it earlier, when we had more assets. But even now there is some renouncings or abandons that the situation does not comprise. France does not have to accept and will not accept settlement which would be incompatible with its more vital interests [applauding on certain seats of the Assembly on the left and at the extreme right]. France will remain present in Far-Orient. Neither our allies, nor our opponents must conserve the least doubt on the signification of our determination. A negotiation has been engaged in Geneva ... I have longly studied the report ... consulted the most qualified military and diplomatic experts. My conviction that a pacific settlement of the conflict is possible has been confirmed. A "cease-fire" must henceforth intervene quickly. The government which I will form will fix itself — and will fix to its opponents — a delay of 4 weeks to reach it. We are today on 17th of June. I will present myself before you before the 20th of July ... If no satisfying solution has been reached at this date, you will be freed from the contract which would have tied us together, and my government will give its dismissal to the President of the Republic."[54]

The Geneva Conference on July 21, 1954, recognized the 17th parallel north as a "provisional military demarcation line," temporarily dividing the country into two zones, Communist North Vietnam and pro-Western South Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords promised elections in 1956 to determine a national government for a united Vietnam. Neither the United States government nor Ngo Dinh Diem's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. With respect to the question of reunification, the non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam, but lost out when the French accepted the proposal of Viet Minh delegate Pham Van Dong,[55] who proposed that Vietnam eventually be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".[56] The United States countered with what became known as the "American Plan", with the support of South Vietnam and the United Kingdom.[57] It provided for unification elections under the supervision of the United Nations, but was rejected by the Soviet delegation.[57] From his home in France, Emperor Bảo Đại appointed Ngô Đình Diệm as Prime Minister of South Vietnam. With American support, in 1955 Diem used a referendum to remove the former Emperor and declare himself the president of the Republic of Vietnam.

When the elections failed to occur, Viet Minh cadres who stayed behind in South Vietnam were activated and started to fight the government. North Vietnam also invaded and occupied portions of Laos to assist in supplying the guerilla fighting National Liberation Front in South Vietnam. The war gradually escalated into the Second Indochina War, more commonly known as the Vietnam War in the West and the American War in Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh

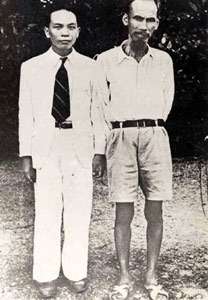

In 1923, Ho Chi Minh moved to Guangzhou, China. In 1925–26, he organized the 'Youth Education Classes' and occasionally gave lectures at the famous Whampoa Military Academy on the revolutionary movement in Indochina. He stayed there in Hong Kong as a representative of the Communist International organization. In June 1931, he was arrested and incarcerated by British police until his release in 1933. He then made his way back to the Soviet Union, where he spent several years recovering from tuberculosis. In 1938, he returned to China and served as an adviser with the Chinese Communist armed forces.

In 1941, Ho Chi Minh, seeing communist revolution as the path to freedom, returned to Vietnam and formed the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi (League for the Independence of Vietnam), better known as the Viet Minh. He spent many years in Moscow and participated in the International Comintern. At the direction of Moscow, he combined the various Vietnamese communist groups into the Indochinese Communist Party in Hong Kong in 1930. Ho created the Viet Minh as an umbrella organization for all the nationalist resistance movements, de-emphasizing his communist social revolutionary background.

Late in the war, the Japanese created a nominally independent government of Vietnam under the overall leadership of Bảo Đại. Around the same time, the Japanese arrested and imprisoned most of the French officials and military officers left in the country. After the French army and other officials were freed from Japanese prisons in Vietnam, they began reasserting their authority over parts of the country. At the same time, the French government began negotiations with both the Viet Minh and the Chinese for a return of the French army to Vietnam north of the 16th parallel.

The Viet Minh were willing to accept French rule to end Chinese occupation. Ho and others had fears of the Chinese, based on China's historic domination and occupation of Vietnam. The French negotiated a deal with the Chinese where pre-war French concessions in Chinese ports such as Shanghai were traded for Chinese cooperation in Vietnam. The French landed a military force at Haiphong in early 1946. Negotiations then took place about the future for Vietnam as a state within the French Union. These talks eventually failed and the Viet Minh fled into the countryside to wage guerrilla war. In 1946, Vietnam created its first constitution.

The British had supported the French in fighting the Viet Minh, armed militias from the religious Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo sects and the Bình Xuyên organized crime groups, which were all individually seeking power in the country. In 1948, as part of a post-colonial solution, the French re-installed Bao Dai as head of state of Vietnam under the French Union. The Viet Minh were militarily ineffective in the first few years of the war and could do little more than harass the French in remote areas of Indochina.

In 1949, the war changed with the triumph of the communists in China on Vietnam's northern border. China was able to give almost unlimited support in terms of weapons and supplies to the Viet Minh, which transformed itself into a conventional army. After World War II, the United States and the USSR entered into the Cold War. The Korean War broke out in 1950 between communist North Korea (DPRK) supported by China and the Soviet Union, and South Korea (ROK) supported by the United States and its allies in the UN.

The Cold War was now turning 'hot' in East Asia, and the American government feared communist domination of the entire region would have deep implications for American interests. The US became strongly opposed to the government of Ho Chi Minh, in part, because it was supported and supplied by China. Ho's government gained recognition from China and the Soviet Union by January 1950 in response to Western support for the State of Vietnam that the French had proposed as an associate state within the French Union. In the French-controlled areas of Vietnam, in the same year, the government of Bao Dai gained recognition by the United States and the United Kingdom.

French domestic situation

The 1946 Constitution creating the Fourth Republic (1946–1958) made France a Parliamentary republic. Because of the political context, it could find stability only by an alliance between the three dominant parties: the Christian Democratic Popular Republican Movement (MRP), the French Communist Party (PCF) and the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). Known as tripartisme, this alliance briefly lasted until the May 1947 crisis, with the expulsion from Paul Ramadier's SFIO government of the PCF ministers, marking the official start of the Cold War in France. This had the effect of weakening the regime, with the two most significant movements of this period, Communism and Gaullism, in opposition.

Unlikely alliances had to be made between left- and right-wing parties in order to form a government invested by the National Assembly, which resulted in strong parliamentary instability. Hence, France had fourteen prime ministers in succession between the creation of the Fourth Republic in 1947 and the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The rapid turnover of governments (there were 17 different governments during the war) left France unable to prosecute the war with any consistent policy according to veteran General René de Biré (who was a lieutenant at Dien Bien Phu).[58] France was increasingly unable to afford the costly conflict in Indochina and, by 1954, the United States was paying 80% of France's war effort, which was $3,000,000 per day in 1952.[59][60]

A strong anti-war movement came into existence in France driven mostly by the then-powerful French Communist Party (outpowering the socialists) and its young militant associations, major trade unions such as the General Confederation of Labour, and notable leftist intellectuals.[61][62] The first occurrence was probably at the National Assembly on March 21, 1947, when the communist deputees refused to back the military credits for Indochina. The following year a pacifist event was organized, the "1st Worldwide Congress of Peace Partisans" (1er Congrès Mondial des Partisans de la Paix, the World Peace Council's predecessor), which took place March 25–28, 1948, in Paris, with the French communist Nobel laureate atomic physicist Frédéric Joliot-Curie as president. Later, on April 28, 1950, Joliot-Curie would be dismissed from the military and civilian Atomic Energy Commission for political reasons.[63]

Young communist militants (UJRF) were also accused of sabotage actions like the famous Henri Martin affair and the case of Raymonde Dien, who was jailed one year for having blocked an ammunition train, with the help of other militants, in order to prevent the supply of French forces in Indochina in February 1950.[58][61] Similar actions against trains occurred in Roanne, Charleville, Marseille, and Paris. Even ammunition sabotage by PCF agents has been reported, such as grenades exploding in the hands of legionaries.[58] These actions became such a cause for concern by 1950 that the French Assembly voted a law against sabotage between March 2–8. At this session tension was so high between politicians that fighting ensued in the assembly following communist deputees’ speeches against the Indochinese policy.[63] This month saw the French navy mariner and communist militant Henri Martin arrested by military police and jailed for five years for sabotage and propaganda operations in Toulon's arsenal. On May 5 communist Ministers were dismissed from the government, marking the end of Tripartism.[63] A few months later on November 11, 1950, the French Communist Party leader Maurice Thorez went to Moscow.

Some military officers involved in the Revers Report scandal (Rapport Revers) such as Salan were pessimistic about the way the war was being conducted,[64] with multiple political-military scandals all happening during the war, starting with the Generals' Affair (Affaire des Généraux) from September 1949 to November 1950. As a result, General Georges Revers was dismissed in December 1949 and socialist Defense Ministry Jules Moch (SFIO) was brought on court by the National Assembly on November 28, 1950. Emerging media played their role. The scandal started the commercial success of the first French news magazine, L'Express, created in 1953.[65] The third scandal was financial-political, concerning military corruption, money and arms trading involving both the French Union army and the Viet Minh, known as the Piastres affair. The war ended in 1954 but its sequel started in French Algeria where the French Communist Party played an even stronger role by supplying the National Liberation Front (FLN) rebels with intelligence documents and financial aid. They were called "the suitcase carriers" (les porteurs de valises).

In the French news, the Indochina War was presented as a direct continuation of the Korean War, where France had fought: a UN French battalion, incorporated in a U.S. unit in Korea, was later involved in the Battle of Mang Yang Pass of June and July 1954.[50] In an interview taped in May 2004, General Marcel Bigeard (6th BPC) argues that "one of the deepest mistakes done by the French during the war was the propaganda telling you are fighting for Freedom, you are fighting against Communism",[51] hence the sacrifice of volunteers during the climactic battle of Dien Bien Phu. In the latest days of the siege, 652 non-paratrooper soldiers from all army corps from cavalry to infantry to artillery dropped for the first and last time of their life to support their comrades. The Cold War excuse was later used by General Maurice Challe through his famous "Do you want Mers El Kébir and Algiers to become Soviet bases as soon as tomorrow?", during the Generals' putsch (Algerian War) of 1961, with limited effect though.[66]

A few hours after the French Union defeat at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, United States Secretary of State John Foster Dulles made an official speech depicting the "tragic event" and "its defense for fifty seven days and nights will remain in History as one of the most heroic of all time." Later on, he denounced Chinese aid to the Viet Minh, explained that the United States could not act openly because of international pressure, and concluded with the call to "all concerned nations" concerning the necessity of "a collective defense" against "the communist aggression".[9]

War crimes and re-education camps

- The Boudarel Affair. Georges Boudarel was a French communist militant who used brainwashing and torture against French Union POWs in Viet Minh reeducation camps.[67] The French national association of POWs brought Boudarel to court for a war crime charge. Most of the French Union prisoners died in the Viet Minh camps and many POWs from the Vietnamese National Army were missing.

- Passage to Freedom was a Franco-American operation to evacuate refugees. Loyal Indochinese evacuated to metropolitan France were kept in detention camps.[68]

- In 1957, the French Chief of Staff with Raoul Salan would use the POWs’ experience with the Viet Minh reeducation camps to create two "Instruction Center for Pacification and Counter-Insurgency" (Centre d'Instruction à la Pacification et à la Contre-Guérilla aka CIPCG) and train thousands of officers during the Algerian War.

- According to Arthur J. Dommen, the Viet Minh assassinated between 100,000 and 150,000 civilians during the war; total civilian deaths are estimated at 400,000.[21][69]

- The French Army tortured Viet Minh prisoners[70]

Other countries' involvement

By 1946, France headed the French Union. As successive governments had forbidden the sending of metropolitan troops, the French Far East Expeditionary Corps (CEFEO) was created in March 1945. The Union gathered combatants from almost all French territories made of colonies, protectorates and associated states (Madagascar, Senegal, Tunisia, etc.) to fight in French Indochina, which was then occupied by the Japanese. About 325,000 of the 500,000 French troops were Indochinese, almost all of whom were used in conventional units.[71]

The Afrique Occidentale Française (AOF) was a federation of African colonies. Senegalese and other African troops were sent to fight in Indochina. Some African alumni were trained in the Infantry Instruction Center no.2 (Centre d'Instruction de l'Infanterie no.2) located in southern Vietnam. Senegalese of the Colonial Artillery fought at the siege of Dien Bien Phu. As a French colony (later a full province), French Algeria sent local troops to Indochina including several RTA (Régiment de Tirailleurs Algériens) light infantry battalions. Morocco was a French protectorate and sent troops to support the French effort in Indochina. Moroccan troops were part of light infantry RTMs (Régiment de Tirailleurs Marocains) for the "Moroccan Sharpshooters Regiment".

As a French protectorate, Bizerte, Tunisia, was a major French base. Tunisian troops, mostly RTT (Régiment de Tirailleurs Tunisiens), were sent to Indochina. Part of French Indochina, then part of the French Union and later an associated state, Laos fought the communists along with French forces. The role played by Laotian troops in the conflict was depicted by veteran Pierre Schoendoerffer's famous 317th Platoon released in 1964.[72] The French Indochina state of Cambodia played a significant role during the Indochina War through its infantrymen and paratroopers.

While Bảo Đại's State of Vietnam (formerly Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina) had the Vietnamese National Army supporting the French forces, some minorities were trained and organized as regular battalions (mostly infantry tirailleurs) that fought with French forces against the Viet Minh. The Tai Battalion 2 (BT2, 2e Bataillon Thai) is infamous for its desertion during the siege of Dien Bien Phu. Propaganda leaflets written in Tai and French sent by the Viet Minh were found in the deserted positions and trenches. Such deserters were called the Nam Yum rats by Bigeard during the siege, as they hid close to the Nam Yum river during the day and searched at night for supply drops.[73] Another allied minority was the Muong people (Mường). The 1st Muong Battalion (1er Bataillon Muong) was awarded the Croix de guerre des théâtres d'opérations extérieures after the victorious Battle of Vinh Yen in 1951.[74]

In the 1950s, the French established secret commando groups based on loyal Montagnard ethnic minorities referred to as "partisans" or "maquisards", called the Groupement de Commandos Mixtes Aéroportés (Composite Airborne Commando Group or GCMA), later renamed Groupement Mixte d'Intervention (GMI, or Mixed Intervention Group), directed by the SDECE counter-intelligence service. The SDECE's "Service Action" GCMA used both commando and guerrilla techniques and operated in intelligence and secret missions from 1950 to 1955.[75][76] Declassified information about the GCMA includes the name of its commander, famous Colonel Roger Trinquier, and a mission on April 30, 1954, when Jedburgh veteran Captain Sassi led the Meo partisans of the GCMA Malo-Servan in Operation Condor during the siege of Dien Bien Phu.[77]

In 1951, Adjutant-Chief Vandenberghe from the 6th Colonial Infantry Regiment (6e RIC) created the "Commando Vanden" (aka "Black Tigers", aka "North Vietnam Commando #24") based in Nam Định. Recruits were volunteers from the Thổ people, Nùng people and Miao people. This commando unit wore Viet Minh black uniforms to confuse the enemy and used techniques of the experienced Bo doi (Bộ đội, regular army) and Du Kich (guerrilla unit). Viet Minh prisoners were recruited in POW camps. The commando was awarded the Croix de guerre des TOE with palm in July 1951; however, Vandenberghe was betrayed by a Viet Minh recruit, commander Nguien Tinh Khoi (308th Division's 56th Regiment), who assassinated him (and his Vietnamese fiancee) with external help on the night of January 5, 1952.[78][79][80] Coolies and POWs known as PIM (Prisonniers Internés Militaires, which is basically the same as POW) were civilians used by the army as logistical support personnel. During the battle of Dien Bien Phu, coolies were in charge of burying the corpses—during the first days only, after they were abandoned, hence giving off a terrible smell, according to veterans—and they had the dangerous job of gathering supply packets delivered in drop zones while the Viet Minh artillery was firing hard to destroy the crates. The Viet Minh also used thousands of coolies to carry the Chu-Luc (regional units) supplies and ammunition during assaults. The PIM were civilian males old enough to join Bảo Đại's army. They were captured in enemy-controlled villages, and those who refused to join the State of Vietnam's army were considered prisoners or used as coolies to support a given regiment.[81]

_Lublin-51.jpg)

One point that the French had a major problem with was the concept of sanctuary. As long as the revolutionaries who are fighting a guerilla war have a sanctuary, in which they can hide out, recoup after losses, and store supplies, it is almost impossible for any foreign enemy to ever destroy them. In the early 1950s, southern China was used as a sanctuary by Viet Minh guerrillas. Several hit and run ambushes were successfully operated against French Union convoys along the neighboring Route Coloniale 4 (RC 4), which was a major supply way in Tonkin (northern Vietnam). One of the most famous attacks of this kind was the battle of Cao Bằng. China supplied the Viet Minh guerrillas with food (thousands of tons of rice), money, medics, arms, ammunition, artillery (24 guns were used at Dien Bien Phu) and other military equipment including a large part of material captured from Chiang Kai-shek's National Revolutionary Army during the Chinese Civil War. Evidences of the Chinese secret aid were found in caves during Operation Hirondelle in July 1953.[82][83] 2,000 Chinese and Soviet Union military advisors trained the Viet Minh guerrilla force to turn it into a full range army.[58] On top of this China sent two artillery battalions at the siege of Dien Bien Phu on May 6, 1954. One operated 12 x 6 Katyusha rockets[84] China and the Soviet Union were the first nations to recognize North Vietnam.

The Soviet Union was the other ally of the Viet Minh, supplying GAZ trucks, truck engines, fuel, tires, arms (thousands of Skoda light machine guns), all kind of ammunitions, anti-aircraft guns (4 x 37 mm type) and cigarettes. During Operation Hirondelle, the French Union paratroopers captured and destroyed tons of Soviet supplies in the Ky Lua area.[82][85] According to General Giap, the Viet Minh used 400 GAZ-51 soviet-built trucks at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Because the trucks were using highly effective camouflage, the French Union reconnaissance planes were not able to notice them. On May 6, 1954, during the siege, Katyusha were successfully used against the outpost. Together with China, the Soviet Union sent 2,000 military advisors to train the Viet Minh and turn it into a fully organized army.[58]

Mutual Defense Assistance Act (1950–1954)

At the beginning of the war, the U.S. was neutral in the conflict because of opposition to European colonialism, because the Viet Minh had recently been their allies, and because most of its attention was focused on Europe where Winston Churchill argued an Iron Curtain had fallen.

Then the U.S. government gradually began supporting the French in their war effort, primarily through the Mutual Defense Assistance Act, as a means of stabilizing the French Fourth Republic in which the French Communist Party was a significant political force. A dramatic shift occurred in American policy after the victory of Mao Zedong's Communist Party of China in the Chinese Civil War. By 1949, however, the United States became concerned about the spread of communism in Asia, particularly following the end of the Chinese Civil War, and began to strongly support the French as the two countries were bound by the Cold War Mutual Defense Programme.[86]

After the Moch–Marshall meeting of September 23, 1950, in Washington, the United States started to support the French Union effort politically, logistically and financially. Officially, US involvement did not include use of armed force. However, recently it has been discovered that undercover (CAT)—or not—US Air Force pilots flew to support the French during Operation Castor in November 1953. Two US pilots were killed in action during the siege at Dien Bien Phu the following year. These facts were declassified and made public more than 50 years after the events, in 2005 during the Légion d'honneur award ceremony by the French ambassador in Washington.[87]

In May 1950, after the capture of Hainan island by Chinese Communist forces, U.S. President Harry S. Truman began covertly authorizing direct financial assistance to the French, and on June 27, 1950, after the outbreak of the Korean War, announced publicly that the U.S. was doing so. It was feared in Washington that if Ho were to win the war, with his ties to the Soviet Union, he would establish a puppet state with Moscow with the Soviets ultimately controlling Vietnamese affairs. The prospect of a communist-dominated Southeast Asia was enough to spur the U.S. to support France, so that the spread of Soviet-allied communism could be contained.

On June 30, 1950, the first U.S. supplies for Indochina were delivered. In September, Truman sent the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to Indochina to assist the French. Later, in 1954, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower explained the escalation risk, introducing what he referred to as the "domino principle", which eventually became the concept of domino theory. During the Korean War, the conflict in Vietnam was also seen as part of a broader proxy war with China and the USSR in Asia.

US Navy assistance (1951–1954)

The USS Windham Bay delivered Grumman F8F Bearcat fighter aircraft to Saigon on January 26, 1951.[88]

On March 2 of that year, the United States Navy transferred the USS Agenor (ARL-3) (LST 490) to the French Navy in Indochina in accordance with the MAAG-led MAP. Renamed RFS Vulcain (A-656), she was used in Operation Hirondelle in 1953. The USS Sitkoh Bay carrier delivered Grumman F8F Bearcat aircraft to Saigon on March 26, 1951. During September 1953, the USS Belleau Wood (renamed Bois Belleau) was lent to France and sent to French Indochina to replace the Arromanches. She was used to support delta defenders in the Hạ Long Bay operation in May 1954. In August, she joined the Franco-American evacuation operation called "Passage to Freedom".

The same month, the United States delivered additional aircraft, again using the USS Windham Bay.[89] On April 18, 1954, during the siege of Dien Bien Phu, the USS Saipan delivered 25 Korean War AU-1 Corsair aircraft for use by the French Aeronavale in supporting the besieged garrison.

US Air Force assistance (1952–1954)

A total of 94 F4U-7s were built for the Aéronavale in 1952, with the last of the batch, the final Corsair built, rolled out in December 1952. The F4U-7s were actually purchased by the U.S. Navy and passed on to the Aéronavale through the U.S. Military Assistance Program (MAP). They were supplemented by 25 ex-U.S.MC AU-1s (previously used in the Korean War) and moved from Yokosuka, Japan, to Tourane Air Base (Da Nang), Vietnam, in April 1952. US Air Force assistance followed in November 1953 when the French commander in Indochina, General Henri Navarre, asked General Chester E. McCarty, commander of the Combat Cargo Division, for 12 Fairchild C-119s for Operation Castor at Dien Bien Phu. The USAF also provided C-124 Globemasters to transport French paratroop reinforcements to Indochina.

Under the codename Project Swivel Chair,[90] on March 3, 1954, twelve C-119s of the 483rd Troop Carrier Wing ("Packet Rats") based at Ashiya, Japan, were painted with France's insignia and loaned to France with 24 CIA pilots for short-term use. Maintenance was carried out by the US Air Force and airlift operations were commanded by McCarty.[87]

Central Intelligence Agency covert operations (1954)

Twenty four Central Intelligence Agency (Civil Air Transport) pilots supplied the French Union garrison during the siege of Dien Bien Phu by airlifting paratroopers, ammunition, artillery pieces, tons of barbed wire, medics and other military materiel. With the reducing Drop zone areas, night operations and anti-aircraft artillery assaults, many of the "packets" fell into Viet Minh hands. The 37 CIA pilots completed 682 airdrops under anti-aircraft fire between March 13 and May 6. Two CAT pilots, Wallace Bufford and James B. McGovern, Jr. were killed in action when their Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar was shot down on May 6, 1954 .[87] On February 25, 2005, the French ambassador to the United States, Jean-David Levitte, awarded the seven remaining CIA pilots the Légion d'honneur.[87]

Operation Passage to Freedom (1954)

In August 1954, in support to the French navy and the merchant navy, the U.S. Navy launched Operation Passage to Freedom and sent hundreds of ships, including USS Montague, in order to evacuate non-communist—especially Catholic—Vietnamese refugees from North Vietnam following the July 20, 1954, armistice and partition of Vietnam. Up to 1 million Vietnamese civilians were transported from North to South during this period,[91] with around one tenth of that number moving in the opposite direction.

Popular culture

Although a kind of taboo in France, "the dirty war" has been featured in various films, books and songs. Since its declasification in the 2000s, television documentaries have been released using new perspectives about the U.S. covert involvement and open critics about the French propaganda used during wartime.

Famous Communist propagandist Roman Karmen was in charge of the media exploitation of the battle of Dien Bien Phu. In his documentary, Vietnam (Вьетнам, 1955), he staged the famous scene with the raising of the Viet Minh flag over de Castries' bunker which is similar to the one he staged over the Berlin Reichstag roof during World War II (Берлин, 1945) and the "S"-shaped POW column marching after the battle, where he used the same optical technique he experimented with before when he staged the German prisoners after the Siege of Leningrad (Ленинград в борьбе, 1942) and the Battle of Moscow (Разгром немецких войск под Москвой, 1942).[92][93]

Hollywood made a film about Dien Bien Phu in 1955, Jump into Hell, directed by David Butler and scripted by Irving Wallace, before his fame as a bestselling novelist. Hollywood also made several films about the war, Robert Florey's Rogues' Regiment (1948). Samuel Fuller's China Gate (1957). and James Clavell's Five Gates to Hell (1959).

The first French movie about the war, Shock Patrol (Patrouille de Choc) aka Patrol Without Hope (Patrouille Sans Espoir) by Claude Bernard-Aubert, came out in 1956. The French censor cut some violent scenes and made the director change the end of his movie which was seen as "too pessismistic".[94] Léo Joannon's film Fort du Fou (Fort of the Mad) /Outpost in Indochina was released in 1963. Another film was The 317th Platoon (La 317ème Section) was released in 1964, it was directed by Indochina War (and siege of Dien Bien Phu) veteran Pierre Schoendoerffer. Schoendoerffer has since become a media specialist about the Indochina War and has focused his production on realistic war movies. He was cameraman for the army ("Cinematographic Service of the Armies", SCA) during his duty time; moreover, as he had covered the Vietnam War he released The Anderson Platoon, which won the Academy Award for Documentary Feature.

Graham Greene's novel The Quiet American takes place during this war.

A Vietnamese software developer made a videogame called 7554 after the date of Battle of Dien Bien Phu to commemorate the First Indochina War from the Vietnamese point of view.

See also

- Hélie Denoix de Saint Marc

- Japanese invasion of French Indochina

- Franco-Thai War

- Japanese coup d'état in French Indochina

- Japanese holdout

- Indochina Wars

- North Vietnamese invasion of Laos

- Second Indochina War

- Third Indochina War

- Cambodian–Vietnamese War

- Pathet Lao

- United Issarak Front

Notes

- ↑ Lee Lanning, Michael (2008). Inside the VC and the NVA. : Texas A&M University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-60344-059-2.

- ↑ Crozier, Brian (2005). Political Victory: The Elusive Prize Of Military Wars. Transaction. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7658-0290-3.

- ↑ Fall, Street Without Joy, p. 63.

- ↑ Logevall, Fredrik (2012). Embers of War: the fall of an empire and the making of America's Vietnam. Random House. pp. 596–9. ISBN 978-0-375-75647-4.

- ↑ "CNN.com – France honors CIA pilots – Feb 28, 2005". Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ Jacques Dalloz, La Guerre d'Indochine 1945–1954, Seuil, Paris, 1987,pp. 129–130, 206

- ↑ Jacques Dalloz (1987). La Guerre d'Indochine 1945–1954. Paris: Seuil. pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben. How Pol Pot Came to Power. London: Verso, 1985. p. 80

- 1 2 henrisalvador. "John Foster Dulles on the fall of Dien Bien Phu". Dailymotion. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- 1 2 "Viện trợ của Trung Quốc đối với cuộc kháng chiến chống Pháp của Việt Nam". Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2013/9311/pdf/DaoDucThuan_2013_02_05.pdf

- ↑ "East Germany – The National People's Army and the Third World".

- ↑ Windrow, Martin (1998). The French Indochina War 1946–1954 (Men-At-Arms, 322). London: Osprey Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 1-85532-789-9.

- ↑ Windrow 1998, p. 23

- ↑ Ford, Dan. "Japanese soldiers with the Viet Minh".

- ↑ Dommen, Arthur J. (2001), The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans, Indiana University Press, pg. 252

- 1 2 Clodfelter, Michael, Vietnam in Military Statistics (1995)

- ↑ Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam 1945–1995. James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts. Chapter 2: The first Indochina war 1945–54

- ↑ Smedberg, M (2008), Vietnamkrigen: 1880–1980. Historiska Media, p. 88

- ↑ Eckhardt, William, in World Military and Social Expenditures 1987–88 (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard.

- 1 2 Dommen, Arthur J. (2001), The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans, Indiana University Press, pg. 252.

- ↑ s:Page:Pentagon-Papers-Part I.djvu/30

- ↑ Fall, Street Without Joy, p. 17.

- ↑ Edward Rice-Maximin, Accommodation and Resistance: The French Left, Indochina, and the Cold War, 1944–1954 (Greenwood, 1986).

- ↑ Flitton, Dave. "Battlefield Vietnam – Dien Bien Phu, the legacy". Public Broadcasting System PBS. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "Interview with Carleton Swift, 1981". Open Vault. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- ↑ "WGBH Open Vault – Interview with Archimedes L. A. Patti, 1981". Retrieved 2015-08-19.

- ↑ "ベトナム独立戦争参加日本人の事跡に基づく日越のあり方に関する研究" (PDF). 井川 一久. Tokyo foundation. October 2005. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "日越関係発展の方途を探る研究 ヴェトナム独立戦争参加日本人―その実態と日越両国にとっての歴史的意味―" (PDF). 井川 一久. Tokyo foundation. May 2006. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (1985). The march of folly: from Troy to Vietnam. Random House, Inc. p. 235. ISBN 0-345-30823-9. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Tuchman 1985, p. 237.

- ↑ Text of Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers General Order no. One, Taiwan Documents Project, http://www.taiwandocuments.org/surrender05.htm

- ↑ Hugh Dyson Walker (November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. pp. 621–. ISBN 978-1-4772-6516-1.

- ↑ Larry H. Addington (2000). America's war in Vietnam: a short narrative history. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-253-21360-6. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Peter Neville (2007). Britain in Vietnam: prelude to disaster, 1945-6. Psychology Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-415-35848-5. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Van Nguyen Duong (2008). The tragedy of the Vietnam War: a South Vietnamese officer's analysis. McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 0-7864-3285-3. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Stein Tønnesson (2010). Vietnam 1946: how the war began. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-520-25602-6. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Elizabeth Jane Errington (1990). Elizabeth Jane Errington; B. J. C. McKercher, eds. The Vietnam War as history. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 63. ISBN 0-275-93560-4. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ "The Vietnam War Seeds of Conflict 1945–1960". The History Place. 1999. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History, (New York: Penguin Books Ltd., 1997), 146

- ↑ Allies Reinforce Java and Saigon, British Paramount News rushes, 1945

- 1 2 Philipe Leclerc de Hauteloque (1902–1947), La légende d'un héro, Christine Levisse-Touzé, Tallandier/Paris Musées, 2002

- ↑ Windrow 2004, p. 90.

- ↑ Barnet, Richard J. (1968). Intervention and Revolution: The United States in the Third World. World Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 0-529-02014-9.

- ↑ Sheehan, Neil (1988). A Bright Shining Lie. New York: Random House. p. 155. ISBN 0-394-48447-9.

- ↑ Cirillo, Roger (2015). The Shape of Battles to Come. Louisville: University Press of Kentucky. p. 187. ISBN 978-0813165752.

- ↑ Trận then chốt Đông Khê. 02 November, 2014.

- ↑ Gras, Yves (1979). Histoire de la Guerre d'Indochine. Paris. p. 408. ISBN 2-259-00478-4.

- 1 2 "La Guerre En Indochine" (video). newsreel. October 26, 1950. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- 1 2 "Bigeard et Dien Bien Phu" (video). TV news. Channel 2 (France). May 3, 2004. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ "dienbienphu.org".

- ↑ Michael C. Howard; Kim Be Howard (2002). Textiles of the Daic Peoples of Vietnam. White Lotus Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-974-7534-97-9.

- ↑ Assemblée Nationale. "Le Gouvernement provisoire et la Quatrième République (1944–1958)".

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 134.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 119.

- 1 2 The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hercombe, Peter (2004). "Dien Bien Phu, Chronicles of a Forgotten Battle". documentary. Transparences Productions/Channel 2 (France).

- ↑ "France's war against Communists rages on" (video). newsreel. News Magazine of the Screen/Warner Bros. May 1952. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ A Bernard Fall Retrospective, presentation of Bernard B. Fall, Vietnam Witness 1953–56, New York, Praeger, 1966, by the Ludwig von Mises Institute

- 1 2 Ruscio, Alain (August 2, 2003). "Guerre d'Indochine: Libérez Henri Martin" (in French). l'Humanité. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ Nhu Tang, Truong (March 12, 1986). "A Vietcong Memoir: An Inside Account of the Vietnam War and Its Aftermath". Vintage. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "France History, IV Republic (1946–1958)" (in French). Quid Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ Patrick Pesnot, Rendez-vous Avec X – Dien Bien Phu, France Inter, December 4, 2004 (Rendez-vous With X broadcast on public station France Inter)

- ↑ "We wanted a newspaper to tell what we wanted" interview by Denis Jeambar & Roland Mihail

- ↑ General Challe's appeal (April 22, 1961)

- ↑ "Accueil". Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ "USS Skagit and Operation Passage To Freedom". self-published. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ https://books.google.com.vn/books?id=MauWlUjuWNsC&pg=PA252&dq=The+Indochinese+Experience+of+the+French+and+the+Americans+100,000+to+150,000&hl=vi&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjt-L-o-9bQAhXFqo8KHZq-A58Q6AEIGTAA#v=onepage&q=The%20Indochinese%20Experience%20of%20the%20French%20and%20the%20Americans%20100%2C000%20to%20150%2C000&f=false

- ↑ indochine.uqam.ca/en/historical-dictionary/1420-torture-french.html

- ↑ Alf Andrew Heggoy and Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Algeria, Bloomington, Indiana, Indiana University Press, 1972, p.175

- ↑ The 317th Platoons script

- ↑ Original audio recordings of General de Castries (Dien Bien Phu) and General Cogny (Hanoi) transmissions on May 7, 1954, during the battle of Dien Bien Phu (from the European Navigator based in Luxembourg)

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives, ECPAD

- ↑ Raymond Muelle; Éric Deroo (1992). Services spéciaux, armes, techniques, missions: GCMA, Indochine, 1950–1954 ... Editions Crépin-Leblond. ISBN 978-2-7030-0100-3.

- ↑ Michel David (2002). Guerre secrète en Indochine: Les maquis autochtones face au Viêt-Minh (1950–1955). ISBN 978-2-7025-0636-3.

- ↑ Dien Bien Phu – Le Rapport Secret, Patrick Jeudy, TF1 Video, 2005

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ Dr. Jacques Cheneau in In Vietnam, 1954. Eight episode

- 1 2 French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ Chinese General Hoang Minh Thao and Colonel Hoang Minh Phuong quoted by Pierre Journoud researcher at the Defense History Studies (CHED), Paris University Pantheon-Sorbonne, in Paris Hanoi Beijing published in Communisme magazine and the Pierre Renouvin Institute of Paris, July 20, 2004.

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ "Replacing France: The Origins of American Intervention in Vietnam" (PDF). book. University Press of Kentucky. July 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "U.S. Pilots Honored For Indochina Service" (PDF). Embassy of France in the U.S. February 24, 2005. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ↑ French Defense Ministry archives

- ↑ "Indochina War: The "good offices" of the Americans". National Audiovisual Institute.

- ↑ Conboy, Morrison, p. 6.

- ↑ Lindholm, Richard (1959). Viet-nam, the first five years: an international symposium. Michigan State University Press

- ↑ Pierre Schoendoerffer interview with Jean Guisnel in Some edited pictures

- ↑ Roman Karmen, un cinéaste au service de la révolution, Dominique Chapuis & Patrick Barbéris, Kuiv Productions / Arte France, 2001

- ↑ "La Cinémathèque de Toulouse".

References

- Buttinger, Joseph (1972). A Dragon Defiant: A Short History of Vietnam. New York: Praeger. OCLC 583077932.

- Chaliand, Gérard (1982). Guerrilla Strategies: An Historical Anthology from the Long March to Afghanistan. California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04443-6.

- Jian, Chen (1993). "China and the First Indo-China War, 1950–54". The China Quarterly. London: School of Oriental and African Studies. 133 (March): 85–110. doi:10.1017/s0305741000018208. ISSN 0305-7410.

- Cogan, Charles G. (2000). "L'attitude des États-Unis à l'égard de la guerre d'Indochine". In Vaïsse, Maurice. Armée française dans la guerre d'Indochine (1946–1954). Bruxelles: Complexe. pp. 51–88. ISBN 2-87027-810-1.

- Conboy, Kenneth; Morrison, James (1995). Shadow War: The CIA's Secret War in Laos. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-58160-535-8.

- Devillers, Philippe; Lacouture, Jean (1969). End of a War: Indochina, 1954. New York: Praeger. OCLC 575650635.

- Dunstan, Simon (2004). Vietnam Tracks: Armor in Battle 1945–75. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-833-2.

- Fall, Bernard B. (1967). Hell in a Very Small Place: The Siege of Dien Bien Phu. Philadelphia: Lippincott. OCLC 551565485.

- Fall, Bernard B (1994). Street Without Joy. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-1700-3.

- Fall, Bernard B. (1963). The Two Viet-Nams: A Political and Military Analysis. New York: Praeger. OCLC 582302330.

- Giap, Vo Nguyen (1971). The Military Art of People's War. New York: Modern Reader. ISBN 0-85345-193-1.

- Hammer, Ellen Joy (1954). The Struggle for Indochina. Stanford: Stanford University Press. OCLC 575892787.

- Humphries, James. F (1999). Through the Valley: Vietnam, 1967–1968. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-55587-821-0.

- Perkins, Mandaley (2006). Hanoi, Adieu: A Bittersweet Memoir of French Indochina. Sydney: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-7322-8197-7.

- Roy, Jules (1963). The Battle of Dienbienphu. New York: Pyramid Books. OCLC 613204239.

- Summers, Harry G. (1995). Historical Atlas of the Vietnam War. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-72223-3.

- Thi, Lam Quang (2002). The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon. University of North Texas. ISBN 1-57441-143-8.

- Vaïsse; editor (2000). L'Armée française dans la guerre d'Indochine (1946–1954). Paris: Editions Complexe. ISBN 978-2-87027-810-9.

- Wiest, Andrew; editor (2006). Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land. Oxford: Osphrey. ISBN 978-1-84603-020-8.

- Windrow, Martin (1998). The French Indochina War, 1946–1954. Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-789-9.

- Windrow, Martin (2004). The Last Valley. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-306-81386-6.

Further reading

- Pescali, Piergiorgio (2010). Indocina. Bologna: Emil. ISBN 978-88-96026-42-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Indochina War. |

- Pentagon Papers, Chapter 2

- Vietnam: The Impossible War

- Fall, Bernard B. Street Without Joy: The French Debacle In Indochina

- ANAPI's official website (National Association of Former POWs in Indochina)

- Hanoi upon the army's return in victory (bicycles demystified) Viet Nam Portal

- Photos about the First War of Indochina (French Defense Archives) (ECPAD) (French)

| 20th century in Vietnam | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World War I | Interwar | World War II | First Indochina War | Vietnam War | Subsidy phase | Doi Moi |