Frontier Strip

The Frontier Strip are the six states in the United States forming a north-south line from North Dakota to Texas. In the American Old West, westward from this strip was the frontier of the United States toward the latter part of the 19th century.[1][2] The Frontier Strip states, or the Last American Frontier,[3][4] form a nearly straight line from north to south and roughly correspond to the Great Plains region of the United States.

Description

The term Frontier Strip is correlated to the 1880 census, where these six states, some of which were territories at the time, were part of the "Frontier Line," sometimes taken to be the 100th meridian west, the geographic designation by the U.S. Census Bureau that proclaimed where the civilization of the Eastern United States ended and the historic American Wild West began. In the 1890 census, it stated, "Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., it can not, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports."[5]

Demographics

The Frontier Strip's land area is 1,642,083.585 km² (634,012.017 sq mi), or 17.92% of U.S. land area. Its population as of the 2000 census was 30,099,199 or 10.695% of U.S. population. Its average population density was 18.33/km² (47.47/sq mi), compared to the U.S. average of 30.72/km² (79.56/sq mi). Its population is heavily tilted towards the south, with both population and population density increasing as one goes state by state from North Dakota in the north towards Texas in the south. Texas by itself has 69.28% of the region's population, living on 41.29% of its land area.

The modern states included in the frontier strip are:

Politics

The Frontier Strip has been one of the most reliably Republican regions of the United States. It was one of the few parts of the country where Republicans had any electoral success during the heavily Democratic years of the Great Depression. The exception to this general rule however could be found in Texas and Oklahoma, both of which were counted as part of the Democratic Solid South for most of the 20th century. The last Democratic presidential candidate to win one of those six states was Jimmy Carter, who won Texas in United States presidential election, 1976.

Regionalism

Although sharing contiguous boundaries, a common frontier era, and many characteristics generally regarded as "western", the states of the Frontier Strip are not usually classified as a true historical/cultural region in their own right. Texas and Oklahoma are often regarded as part of the South or Southwest, while those to the north are generally grouped with the Midwest. None are part of the West today as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.[6]

Climate

The climate of the Frontier Strip states varies considerably, both north to south and east to west. In the northern parts, a humid-continental climate (warm summers, cold winters) prevail, while a humid-subtropical (hot summers, mild winters) is the general rule in southern sections. In the far western areas of all of these states, semi-arid conditions exist. This is characterized by relatively low amounts of rainfall, although the average monthly temperatures will vary considerably from north to south. Perhaps the most notable weather feature of the Frontier Strip states is its reputation for violent weather.

Many of these states make up a large portion of what it often referred to as Tornado Alley. The combinations of warm humid air from the southeast and proximity to the cold fronts coming in from Canada or the far western United States. along with a natural humidity boundary known as a dry line, make it prime ground for being the most tornado-prone region in the world. Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas alone account for a third of all recorded tornadoes in the United States, and parts of the same are often referred to as the "heart of tornado alley."

Frontier history

Frontier Strip events

|

The numerous native tribes of North America stretched throughout the Great Plains. In the area, the Blackfoot Confederacy and the Sioux (the Lakota people) lead lives of hunting and gathering.

Opening of the frontier area

Native Americans

Eastern portions of the Great Plains were inhabited by tribes who lived in semipermanent villages of earth lodges, such as the Arikara, Mandan, Pawnee and Wichita.

Louisiana Purchase era

An influence in the frontier strip were the French. It was from the French that the United States acquired the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. This significantly expanded the country's borders. The Lewis and Clark expedition (1804–1806) was the first United States overland expedition across the west frontier, to the Pacific coast, and then back, led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark. The expedition passed through the area of what is now Kansas City and Omaha, Nebraska.

Following the Lewis and Clark expeditions, Major Stephen H. Long led the Yellowstone and Missouri expeditions of 1819-1820, but his categorizing of the Great Plains as arid and useless led to the region getting a bad reputation as the "Great American Desert", which discouraged settlement in that area for several decades.

Trails, roads, and routes

The 1821 opening of the Santa Fe Trail ("Santa Fe Road") by William Becknell allowed commercial trade between Kansas City, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico, until 1880. The Southwest Trail was another pioneer route that was the primary route for American settlers bound for Texas. The Mormon Trail was the overland route the Mormon pioneers followed west from Nauvoo, Illinois to Salt Lake Valley, establishing Salt Lake City, Utah in 1846.

The Oregon Trail was a key overland migration route on which pioneers traveled across the North American continent in wagons. This trail helped the United States implement its cultural goal of Manifest Destiny, that is to build a great nation spanning the North American continent. The Oregon Trail spanned over half the continent as the wagon trail proceeded over 2,000 miles west through territories and land later to become six U.S. states (Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon). Between 1841 and 1869, the Oregon Trail was used by settlers to the Northwest and West Coast areas of what is now the United States. The California Trail, sharing a portion of the Oregon Trails route, was another major overland emigrant route across the American West from Missouri to California in the middle 19th century. It was used by 250,000 farmers and gold-seekers to reach the California gold fields and farm homesteads in California beginning in the late 1840s.

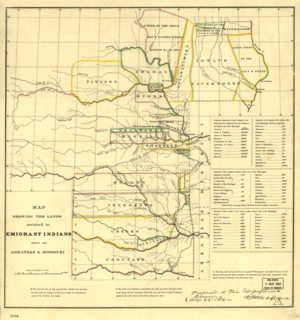

Indian Territory

Indian territories was land set aside within the United States for the use of Native Americans. The general borders were set by the Indian Intercourse Act of 1834. It was more properly "Indian territory" (lower-case T) than "Indian Territory" (capital T) because the name referred to the unorganized lands set aside for Native Americans. The Indian Territory served as the destination for the policy of Indian Removal, a policy pursued intermittently by American presidents early in the nineteenth century, but aggressively pursued by President Andrew Jackson after the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

The Five Civilized Tribes in the South were the most prominent tribes displaced by the policy, a relocation that came to be known as the Trail of Tears during the Choctaw removals starting in 1831. The trail ended in what is now Arkansas and Oklahoma, where there were already many Native Americans living in the territory, as well as whites and escaped slaves. Other tribes, such as the Delaware, Cheyenne, and Apache were also forced to relocate to the Indian territory.

Settlement of Texas

Texas was part of New Spain up through the first two decades of the 19th Century, but Spain was unable to attract colonists to Texas from Spain or from other New World colonies.[12] By the late 18th century, Texas was one of the least populated regions of New Spain, with fewer than two inhabitants per square league.[13] The population was relatively stagnant, having grown only to 3,169 individuals in 1790 from 3,103 in 1777.[14] In 1803 The United States purchased the Louisiana Territory, and insisted that its purchase also included most of West Florida and all of Texas.[15] Spain thus saw Texas as an important buffer region between itself and the United States, and encouraged settlement by non-Spaniards as long as they converted to Catholicism and swore an oath of loyalty to Spain. Moses Austin received an empresarial grant to bring 300 families of settlers to Texas from the United States, but died before he was able to do so. His son Stephen F. Austin came to Texas to assert his father's claim, during which time Mexico declared its independence from Spain. Mexico enacted the General Colonization Law, which enabled all heads of household, regardless of race or immigrant status, to claim land in Mexico.[16] Mexico had neither manpower nor funds to protect settlers from near-constant Comanche raids and it hoped that getting more settlers into the area could control the raids. The government liberalized its immigration policies, allowing for settlers from the United States to immigrate to Texas.[17] The Mexican authorities honored his father's grant, and Austin advertised the opportunity in New Orleans, stating that the land was available along the Brazos and Colorado Rivers.[18] A family of a husband, wife and two children would receive 1,280 acres (520 ha) at twelve and a half cents per acre. Farmers could get 177 acres (72 ha) and ranchers 4,428 acres (1,792 ha). In December 1821, the first U.S. colonists crossed into the granted territory by land and sea, on the Brazos River in present-day Brazoria County, Texas. Twenty-three other empresarios brought settlers to the state, the majority from the United States of America.[19]

The number of Anglo settlers grew quickly in a short time, many escaping debts incurred during the Panic of 1819.[20] Many of these Anglo settlers were slaveholders, and in 1829 Mexico ordered that all slaves be freed in 1830.[21][22] The slavery issue exacerbated cultural, linguistic, and religious differences between the mostly Anglo settlers in Texas and the Mexican government. Texas' remoteness from the capital in Mexico City also led Texas settlers to feel they were neglected by Mexico, and some settlers from the United States had come to Texas with the intent to ultimately make it part of the United States as a fulfillment of Manifest Destiny. Although Mexico implemented several measures to appease the colonists,[23] Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna's measures to transform Mexico from a federalist to a centralist state provided an excuse for the Texan colonists to revolt.[24]

The vague unrest erupted into armed conflict on October 2, 1835 at the Battle of Gonzales, when Texans repelled a Mexican attempt to retake a small cannon.[25][26] This launched the Texas Revolution, and over the next three months, the Texian Army successfully defeated all Mexican troops in the region.[27]

On March 2, 1836, Texans signed the Texas Declaration of Independence at Washington-on-the-Brazos, effectively creating the Republic of Texas. The revolt was justified as necessary to protect basic rights and because Mexico had annulled the federal pact. The majority of the colonists were from the United States; they said that Mexico had invited them to move to the country, but they were determined "to enjoy" the republican institutions to which they were accustomed in their native land.[28] The Texan revolutionaries achieved final victory on April 21, 1836, when the Texian Army attacked Santa Anna's forces near the present-day city of Houston at the Battle of San Jacinto.[29] They captured Santa Anna and forced him to sign the Treaties of Velasco, ending the war.[30][31] The Republic of Texas applied for admission as a U.S. state, becoming a state in 1845. Mexican government called this an act of war, and the Mexican-American War began. The war ended with a U.S. victory, and Mexico ceded modern states California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and later Gadsden Purchase.

Post-war Texas grew rapidly as migrants poured into the cotton lands of the state.[32] German immigrants started to arrive in the early 1840s because of negative economic, social and political pressures in Germany. In 1842, German nobles organized the Adelsverein, banding together to buy land in central Texas to enable German settlement. The Revolutions of 1848 acted as a catalyst for so many immigrants that they became known as the "Forty-Eighters." Many were educated artisans and businessmen. Germans continued to arrive in considerable numbers until 1890.[33][34]

The first Czech immigrants started their journey to Texas on August 19, 1851, headed by Jozef Šilar. Attracted to the rich farmland of Central Texas, Czechs settled in the counties of Austin, Fayette, Lavaca, and Washington. The Czech-American communities are characterized by a strong sense of community, and social clubs were a dominant aspect of Czech-American life in Texas. By 1865, the Czech population numbered 700; by 1940 there were more than 60,000 Czech-Americans in Texas.[35]

With their investments in cotton lands and slaves, Texas planters established cotton plantations in the eastern districts. The central area of the state was developed more by subsistence farmers who seldom owned slaves.[36]

During the American Civil War, Texas had joined the Confederate States of America. The Confederacy was defeated, and Union Army troops arrived in Texas on June 19, 1865 to take possession of the state, restore order, and enforce the emancipation of slaves. The date is now commemorated as the holiday Juneteenth. On June 25, troops raised the American flag in Austin, the state capital.[37] During the Civil War, Federal troops had abandoned frontier forts, and the state struggled to defend western settlements from depredation by Comanches Apaches, and Kiowa, but with the arrival of U.S. troops at the end of the war, these groups were soon driven out of Texas, opening up large areas of the western two-thirds of the state to settlement.[38] Settlers, especially from the war-torn Deep South, saw Texas, that had been relatively untouched by the war and still had vast unsettled land, as a place of opportunity. The state Bureau of Immigration estimated that in 1873 as many as 125,000 people arrived, over 100,000 of these being from older Southern states.From a population of 604,215 in 1860, the state's numbers increased to 818,579 by 1870, and estimates indicated that it had reached over a million by the end of Reconstruction.[39][40]

Westward expansion

The Pony Express Trail from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, was also in use around this time. It was 1840 miles in length. The Pony Express Trail traversed the states of Missouri and California and the intrevening Utah Territory, Nebraska Territory, and Kansas Territory lands (the present day states include: Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and California). It only stayed in operation for 18 months, between April 1860 and October 1861, being replaced by the telegraph.

Wild Bill Hickok, in 1855, was a stagecoach driver on the Santa Fe route and Oregon Trail. His gunfighting skills led to his nickname. He lived a while in Johnson County, Kansas and later was a town constable in Nebraska. He became well known for single-handedly capturing the McCanles gang, through the use of a ruse. On several other occasions, Hickok confronted and killed several men while fighting alone.

Kansas-Nebraska territory

By the mid-1850s, the Kansas territory had a population of only a few hundred settlers but it became the focus of the slavery question. Of its neighboring states, Missouri was a slave state and Iowa was not. With the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, Congress repealed the Missouri Compromise which blocked slavery in Kansas, instead leaving the decision up to Kansas. The stakes were high. Adoption of slavery in Kansas would have given the slave states a two-vote majority in the Senate and abolitionists were intent on blocking that.

To influence the territorial decision, abolitionists (also called "Jayhawkers" or "Free-soilers") financed the migration of anti-slavery settlers. But pro-slavery advocates secured the outcome of the territorial vote by bringing in "Border Ruffians", rowdies from Missouri who stuffed ballot boxes and intimidated voters. The anti-slavers then sent Sharps rifles ("Beecher's Bibles") and ammunition to supporters in Kansas, leading to widespread violence and destruction.

Bleeding Kansas, the Border War, was a series of violent events, involving anti-slavery Free-Soilers and pro-slavery "Border Ruffian" elements, that took place in the Kansas Territory and the western frontier towns roughly between 1854 and 1858. At the heart of the conflict was the question of whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free state or slave state. As such, Bleeding Kansas was a proxy war between Northerners and Southerners over the issue of slavery in the United States.

Dred Scott

The Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1857 declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional and that Congress had no authority to exclude slavery from the territories, thus opening these areas to slavery again depending on the local vote. Despite the efforts by presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan to influence Kansas territorial governors to vote pro-slavery, Kansas voted to become a free state and the thirty-fourth state of the Union in 1861. The conflict also helped to foster the organization and development of the Republican Party in 1856, a mixture of free-soilers, expansionists, and federalists who opposed the extension of slavery into the Western territories.

Civil War era

Abraham Lincoln, an early Republican, made clear his position on slavery in the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates which helped propel him to the presidency in 1860, "Never forget that we have before us this whole matter of the right or wrong of slavery in this Union, though the immediate question is as to its spreading out into new Territories and States." Lincoln branded slavery as a "monstrous injustice" and a "moral, social, and political evil". The Territorial Abolition Act became law on June 19, 1862 ending slavery in all the territories.[41] During the war two other important acts were passed which impacted the West—the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railroad Act.[42]

At the outset of the Civil War, Westerners looked to the Civil War to settle the question of slavery in their territories. But they also feared that the federal government would be too preoccupied with the war to worry about the stability of the territorial governments and that lawlessness might spread. The Dred Scott Decision had made slavery legal in all of the territories.

In Kansas, a major area of conflict building up to the war, was the scene of only one battle, at Mine Creek. But its proximity to Confederate states enabled guerillas, such as Quantrill's Raiders, to attack Union strongholds, causing considerable damage. Both sides attacked civilians, murdering and plundering with little discrimination, creating an atmosphere of terror.

In Texas, citizens voted to join the Confederacy. Local troops took over the federal arsenal in San Antonio, with plans to grab the territories of New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado, and possibly California. At the Battle of Glorieta Pass, the Texans' campaign was defeated by Union troops from Colorado and from Fort Union.

The decreased presence of Union troops in the West left behind untrained militias which encouraged native uprisings and skirmishes with settlers. President Lincoln appears to have had little time to formulate new Indian policy. Some tribes took sides in the war, even forming regiments that joined the Union or the Confederate cause, while others took the opportunity to avenge past wrongs by the federal government. Within the "Indian Territory" (later Oklahoma), conflicts arose among the Five Civilized Tribes, many of whom sided with the South, being slaveholders themselves.

Homestead Act

In 1862, Congress passed three important bills that impacted the land system. The Homestead Act granted 160 acres (65 ha) to each settler who improved the land for five years, to citizens and non-citizens including squatters, for no more than modest filing fees. If a six months residency was complied with, the settler then had the option to buy the parcel at $1.25 per acre. The property could then be sold or mortgaged and neighboring land acquired if expansion was desired. Though the act was on the whole successful, the 160-acre (0.65 km2) size of parcels was not large enough for the needs of Western farmers and ranchers.

Reconstruction west

Post-Civil War pioneers

After the Civil War, much of the Great Plains became open range, hosting ranching operations where anyone was theoretically free to run cattle. In the spring and fall, roundups were held and the new calves were branded and the cattle sorted out for sale. Ranching began in Texas and gradually moved northward. Texas cattle were driven north to railroad lines in cities Dodge City, Kansas and Ogallala, Nebraska; from there, cattle were shipped eastward. Many foreign, especially British, investors financed the great ranches of the era. Overstocking of the range and the terrible winter of 1886 eventually resulted in a disaster, with many cattle starved and frozen. From then onward, ranchers generally turned to raising feed in order to keep their cattle alive over winter. This settlement led to the near-extinction of the bison and the removal of the Native Americans to Indian reservations in the 1870s.

Many from the East Coast and Europe were lured west by reports from relatives and by extensive advertising campaigns promising "the Best Prairie Lands", "Low Prices", "Large Discounts For Cash", and "Better Terms Than Ever!". The new railroads provided the opportunity for migrants to go out and take a look, with special "land exploring tickets", the cost of which could be applied to land purchases offered by the railroads. Some migrants went west reluctantly, particularly women tied to their husbands economically, who viewed the dangers of the West more objectively. The truth was that farming the plains was indeed more difficult than back east. Water management was more critical, lightning fires more prevalent, weather more extreme, rainfall less predictable.

Most migrants, however, put those concerns aside. Their chief motivation to move west was to find a better economic life than the one they had. Farmers sought larger and more fertile areas; merchants and tradesman new customers and less competitive markets; laborers higher paying work and better conditions. In many cases, migrants sank their roots in communities of similar religious and ethnic backgrounds. For example, Swedes to South Dakota, Norwegians to North Dakota, and German Mennonites in Kansas.

Concerning African-Americans, the number of blacks in the West remained at only a few thousand throughout the 19th century. However, if Texas is counted as part of the West, these numbers increase significantly as, being a former Southern slave state, hundreds of thousands of blacks resided within (by the end of the century, the numbers were some 620,000). Blacks did participate in nearly all segments of Western society but many lived in segregated communities. They served in expeditions that mapped the West and as fur traders, miners, cowboys, Indian fighters, scouts, woodsmen, farm hands, saloon workers, cooks, and outlaws. The famed Buffalo Soldiers were members of the Negro regiments of the U.S. Army and they played a substantial role in fighting the Plains Indians and the Apache in Arizona. Relatively few freed slaves, known as "Exodusters", became prairie settlers in all-black towns like Nicodemus, Kansas.

Transcontinental railroad

Concerning the transcontinental rails through the area, existing lines, particularly belonging to the Union Pacific, had already reached westward to Omaha, Nebraska, about halfway across the continent. Building the railroad required six main activities: surveying the route, blasting a right of way, building tunnels and bridges, clearing and laying the roadbed, laying the ties and rails, and maintaining and supplying the crews with food and tools. The work was highly labor-intensive, using mostly plows, scrapers, picks, axes, chisels, sledgehammers, and handcarts.

The transcontinental railroad spurred the development of trunk and feeder lines and the rapid growth of Omaha specifically, creating a rail network extending from the city that eventually reached over most of the West. The railroads made possible the transformation of the United States from an agrarian society to a modern industrial nation. Not only did they bring eastern products west and agricultural products east, but they also helped the establishment of western branches of eastern companies. Mail order businesses grew rapidly, bringing city products to rural families, sometimes dominating local companies and forcing them out of business.

The building and the operation of railroads, which required vast amounts of coal and lumber, spurred the timber and mining industries. Most industries benefited from the lower costs of transportation and the expanding markets made possible by the railroads. Railroads also had a profound social effect. Rail travel brought immigrant families to the West as women were less intimidated by the rail journey west than by wagon. The greater numbers of women and children migrating west helped stabilize and tame some of the wild frontier towns, as these settlers organized and demanded schools, law enforcement, churches, and other institutions supportive of family life.

Native bison, European cattle

The rise of the cattle industry and the cowboy is directly tied to the demise of the huge bison herds of the Great Plains.

Plains buffalo herds

Once numbering over 25 million, bison were a vital resource animal for the Plains Indians, providing food, hides for clothing and shelter, and bones for implements. Drought, loss of habitat, disease, and over-hunting steadily reduced the herds through the 19th century to the point of near extinction. Overland trails and growing settlements began to block the free movement of the herds to feeding and breeding areas. Initially, commercial hunters sought bison to make "pemmican," a mixture of pounded buffalo meat, fat, and berries, which was a long-lasting food used by trappers and other outdoorsmen. Not only did white hunters impact the herds, but Indians who arrived from the East also contributed to their reduction. Adding to the kill was the wanton slaughter of bison by sportsmen, migrants, and soldiers. Shooting bison from passing trains was common sport. However, the greatest negative effect on the herds was the huge markets opened up by the completion of the transcontinental railroad. Hides in great quantities were tanned into leather and fashioned into clothing and furniture. Killing far exceeded market requirements, reaching over one million per year. As many as five bison were killed for each one that reached market, and most of the meat was left to rot on the plains and at trackside after removal of the hides. Skulls were often ground for fertilizer. A skilled hunter could kill over 100 bison in a day.

By the 1870s, the great slaughter of bison had a major impact on the Plains Indians, dependent on the animal both economically and spiritually. Soldiers of the U.S. Army deliberately encouraged and abetted the killing of bison as part of the campaigns against the Sioux and Pawnee, in an effort to deprive them of their resource animal and to demoralize them.

Cattle industry

The sharp decline of the herds of the Plains created a vacuum which was exploited by the growing cattle industry. Spanish cattlemen had introduced cattle ranching and longhorn cattle to the Southwest in the 17th century, and the men who worked the ranches, called "vaqueros", were the first "cowboys" in the West. After the Civil War―with railheads available at Abilene, Kansas City, Dodge City, and Wichita―Texas ranchers raised large herds of longhorn cattle and drove them north along the Western, Chisholm, and Shawnee trails. The cattle were slaughtered in Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City. The Chisholm Trail, laid out by cattleman Joseph McCoy along an old trail marked by Jesse Chisholm, was the major artery of cattle commerce, carrying over 1.5 million head of cattle between 1867 and 1871 over the 800 miles (1,300 km) from south Texas to Abilene, Kansas. In 1871, the Kansas City Stockyards boomed in the city's West Bottoms because of their central location in the country and their proximity to trains. They became second only to Chicago's in size, and the city itself was identified with its famous Kansas City steak.

The long cattle drives were treacherous, especially crossing dangerous waters and when facing hostile Indians or rustlers looking to make off with their cattle. A typical drive would take three to four months and contained two miles (3 km) of cattle six abreast. Despite the risks, the long Texas drives proved very profitable and attracted investors from the United States and abroad. The price of one head of cattle raised in Texas was about $4 but was worth more than $40 back East.

By the 1870s and 1880s, cattle ranches expanded further north into new grazing grounds and replaced the bison herds in Nebraska and the Dakota territory, using the rails to ship to both coasts. Many of the largest ranches were owned by Scottish and British financiers. Gradually, longhorns were replaced by the American breeds of Hereford and Angus, introduced by settlers from the Northwest. Though less hardy and more disease-prone, these breeds produced better tasting beef and matured faster.

In the late 1880s, disaster struck the cattle industry. Overgrazing, harsh weather, and competition from sheep ranches led to a sharp price drop as ranchers gave up on cattle and sold their herds into a falling market. Sheep grazing took over as sheep were easier to feed and needed less water. However, sheep also helped cause ecological changes that enabled foreign grasses to invade the Plains and also caused increased erosion. Open range cattle ranching came to an end and was replaced by barbed wire spreads where water, breeding, feeding, and grazing could be controlled. This led to "fence wars" which erupted over disputes about water rights. Cattlemen and sheep ranchers sometimes engaged in violence against each other as did large and small cattle ranchers.

Cowboy's duties

Before a drive, a cowboy's duties included riding out on the range and bringing together the scattered cattle. All cattle would be sorted, roped, and branded, and most male cattle were castrated. Later, cattle also needed to be dehorned and examined and treated for infections. On the long drives, the cowboys had to keep the cattle moving and in line. The cattle had to be watched day and night as they were prone to stampedes and straying. The work days often lasted fourteen hours, with just six hours of sleep. It was grueling, dusty work, with just a few minutes of relaxation before and at the end of a long day. On the trail, drinking, gambling, brawling, and even cursing was often prohibited and fined. It was often monotonous and boring work. Food was barely adequate and consisted mostly of bacon, beans, bread, coffee, dried fruit, and potatoes. On average, cowboys earned $30 to $40 per month. Because of the heavy physical and emotional toll, it was unusual for a cowboy to spend more than seven years on the range. As open range ranching and the long drives gave way to fenced in ranches in the 1880s, the glory days of the cowboy came to an end, and the myths about the "free living" cowboy began to emerge.

Western code and cowboys

A new code of behavior was becoming acceptable in the West. People no longer had a duty to retreat when threatened. This was a departure from British common law that said you must have your back to the wall before you could protect yourself with deadly force. Many of the cowboys were veterans of the Civil War, particularly from the Confederacy, who returned to ruined home towns and found no future, so they went west looking for opportunities. Some were Blacks, Hispanics, and even Native Americans, Britons, and Scotsmen. Nearly all were in their twenties or teens. The earliest cowboys in Texas learned their trade, adapted their clothing, and took their jargon from the Mexican vaqueros or "buckaroos", the heirs of Spanish cattlemen from Andalusia in Spain. Chaps, the heavy protective leather trousers worn by cowboys, got their name from the Spanish "chaparreras", and the rope was derived from "la reata". However, following the Civil War and the resulting cattle-boom era, it was the drover tradition which dominated in Texas (as opposed to vaquero tending and herding) and the habits were more and more derived from the Old South cattle drovers. As many of them were former Confederate soldiers or sons of the same, they preferred the "McClellan" style saddle rather than the traditional Mexican type.

All the distinct clothing of the cowboy—boots, saddles, hats, pants, chaps, slickers, bandannas, gloves, and collar-less shirts—were practical and adaptable, designed for protection and comfort. The cowboy hat quickly developed the capability, even in the early years, to identify its wearer as someone associated with the West. The most enduring fashion adapted from the cowboy, popular nearly worldwide today, are "blue jeans", originally made by Levi Strauss for miners in 1850. But it was the cowboy hat, that came to symbolize the American West.

Cow-towns and lawmen

While the Eastern United States was beginning to experience the Second Industrial Revolution (which started around 1871), the frontier was beginning to fill up with people. In the early days of the wild west, a great deal of the land was in the public domain, open both to livestock raising as open range and to homesteading. Throughout much of the Old West, there was little to no local law enforcement, and the military had only concentrated presence at specific locations. Buffalo hunters, railroad workers, drifters and soldiers scrapped and fought, leading to the shootings where men died "with their boots on."

The early years of male-dominated life in cattle towns gave way to a more balanced community of farm families and small businesses as the boom passed. Though lawlessness, prostitution, and gambling were significant in cattle towns, especially early on, the greed factor in the towns added an extra element of danger and violence. Since these towns grew rapidly, law and order often took a while to establish itself. Vigilante justice did occur, but in many cases, it subsided when adequate police forces were appointed. While some vigilante committees served the public good fairly and successfully in the absence of law officers and judges, more often than not vigilantism was motivated by bigotry and base emotion and produced imperfect justice directed at those considered socially inferior.

In the towns, state houses, dance halls and saloons catered to the Texas cattle drive trade. The historic Chisholm Trail was used for cattle drives. The trail ran for 800 miles (1,290 km) from south Texas to Abilene, Kansas, and was used from 1867 to 1887 to drive cattle northward to the railhead of the Kansas Pacific Railway, where they were shipped eastward. Cattle rustling was a sometimes serious offense and was always a hazard for the expeditions. It could result in the rustler's lynching by vigilantes (but most stories of this type are fictional). Mexican rustlers were a major issue during the American Civil War, with the Mexican government being accused of supporting the habit. Texans likewise stole cattle from Mexico, swimming them across the Rio Grande.

Anchoring the booming cattle industry of the 1860s and 1870s were the cattle towns in Kansas. Cattle towns such as Abilene and Ellsworth experienced a short period of boom and bust lasting about five years. The cattle towns would spring up as land speculators would rush in ahead of a proposed rail line and build a town and the supporting services attractive to the cattlemen and the cowboys. If the railroads complied, the new grazing ground and supporting town would secure the cattle trade. However, unlike the mining towns which in many cases became ghost towns and ceased to exist after the ore played out, cattle towns often evolved from cattle to farming and continued on after the grazing lands were exhausted. In some cases, resistance by moral reformers and alliances of businessmen drove the cattle trade out of town. Ellsworth, on the other hand, floundered as the result of Indian raids, floods, and cholera.

Fort Dodge, Kansas, was established in 1859 and opened in 1865 on the Santa Fe Trail near the present site of Dodge City, Kansas (which was established in June 1872). The fort offered some protection to wagon trains and the U.S. mail service, and it served as a supply base for troops engaged in the Indian Wars. By the end of 1872, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad crossed Kansas. Dodge City acquired its legacy of lawlessness and gun-slinging and its infamous burial place — Boot Hill Cemetery. It was used until 1878. Dodge City was the buffalo capital until mass slaughter destroyed the huge herds and left the prairie littered with decaying carcasses. Law and order came into Dodge City with such law officers as W. B. 'Bat' Masterson, Ed Masterson, Wyatt Earp, Bill Tilghman, H. B. 'Ham' Bell and Charlie Bassett. The city passed an ordinance that guns could not be worn or carried north of the "deadline," which was the railroad tracks.

A contemporary eyewitness of Hays City, Kansas paints a vivid image of a cattle town:

| “ | "Hays City by lamplight was remarkably lively, but not very moral. The streets blazed with a reflection from saloons, and a glance within showed floors crowded with dancers, the gaily dressed women striving to hide with ribbons and paint the terrible lines which that grim artist, Dissipation, loves to draw upon such faces... To the music of violins and the stamping of feet the dance went on, and we saw in the giddy maze old men who must have been pirouetting on the very edge of their graves."[43] | ” |

To control violence, sometimes cowboys were segregated into brothel districts away from the main part of town. Free-shooting brawls, also known as "hurrahing", were not as frequent as in the movies. In Wichita, handguns were outlawed within city limits and in many towns some form of gun control existed. Also unlike in the movies, marshals rarely shot outlaws, especially in the middle of Main Street in a showdown.

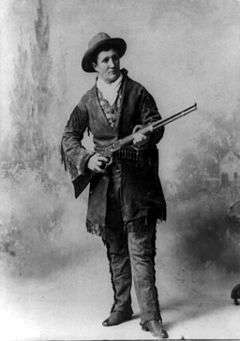

Wild Bill and Calamity Jane

After the Civil War, Wild Bill Hickok became an army scout and a professional gambler. Hickok's killing of Whistler the Peacemaker with a long range rifle shot had influence in preventing the Sioux from uniting to resist the settler incursions into the Black Hills. In 1876, Calamity Jane settled in the area of Deadwood, South Dakota, in the Black Hills region where she was close friends with Wild Bill Hickok and Charlie Utter, all having traveled in Utter's wagon train. Jane later claimed to have been married to Hickok and that Hickok was the father of her child; however, this story is viewed with skepticism.

On August 2, 1876, while playing poker in Deadwood (then part of the Dakota Territory but on Indian land), Hickok could not find an empty seat in the corner where he always sat in order to protect himself against sneak attacks from behind, and he instead sat with his back to the door; unfortunately, his previous caution proved wise, since he was shot in the back of the head with a double-action .45 caliber revolver by Jack McCall. The motive for the killing is still debated. It is claimed that, at the time of his death, Hickok held a pair of aces and a pair of eights, with all cards black; this has since been called a "dead man's hand".

Frontier Indian Wars

Military forts and outposts

The establishment of U.S. military forts moved with it, representing and maintaining federal sovereignty over new territories. The military garrisons usually lacked defensible walls but were seldom attacked. They served as bases for troops at or near strategic areas, particularly for counteracting the Indian presence. For example, Fort Laramie and Fort Kearny helped protect immigrants crossing the Great Plains. Forts were constructed to launch attacks against the Sioux. As Indian reservations sprang up, the military set up forts to protect them. Forts also guarded the Union Pacific and other rail lines. Other important forts were Fort Sill (Oklahoma), and Fort Worth (Texas). By the 1890s, with the threat from Indian nations eliminated, and with migrant populations increasing enough to provide their own law enforcement, most frontier forts were abandoned. Fort Omaha (Nebraska) was home to the Department of the Platte, and was responsible for outfitting most Western posts for more than 20 years after its founding in the late 1870s.

Settlements and conflagrations

As settlement sped up across the West after the transcontinental railroad was completed, clashes with Native Americans of the Plains and southwest reached a final phase. The military's mission was to clear the land of free-roaming Indians and put them onto reservations. The stiff resistance after the Civil War of battle-hardened, well-armed Indian warriors resulted in the Indian Wars.

Red Cloud's War was led by the Lakota chief Makhpyia luta (Red Cloud) against the military who were erecting forts along the Bozeman trail. It was the most successful campaign against the U.S. during the Indian Wars. By the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), the U.S. granted a large reservation to the Lakota, without military presence or oversight, no settlements, and no reserved road building rights. The reservation included the entire Black Hills.

The Black Hills War was conducted by the Lakota under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The conflict began after repeated violations of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) once gold was discovered in the hills. One of its famous battles was the Battle of the Little Bighorn, in which combined Sioux and Cheyenne forces defeated the 7th Cavalry, led by General George Armstrong Custer.

The end of the Indian Wars came at the Wounded Knee Massacre (December 29, 1890) where Sitting Bull's half-brother, Big Foot, and some 200 Sioux were killed by the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment. Only thirteen days before, Sitting Bull had been killed with his son Crow Foot in a gun battle with a group of Indian police that had been sent by the American government to arrest him.

Closing the frontier

Buffalo Bill Wild West Show

In Omaha, Nebraska, in 1883, Cody founded the "Buffalo Bill Wild West Show," a circus-like attraction that toured annually: Annie Oakley and Sitting Bull both appeared in the show. In 1887, he performed in London in celebration of the Jubilee year of Queen Victoria and toured Europe in 1889. The frontiersman and showman Buffalo Bill (William Cody) toured the United States starring in plays based loosely on his Western adventures. His part typically included an 1876 incident at Warbonnet Creek where he scalped a Cheyenne warrior, purportedly in revenge for the death of George Armstrong Custer.

Oklahoma land rush

In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison authorized the opening of 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of unoccupied lands in the Oklahoma territory acquired from the native tribes. On April 22, over 100,000 settlers and cattlemen (known as "boomers") lined up at the border, and with the army's guns and bugles giving the signal, began a mad dash into the newly opened land to stake their claims (Land Run of 1889). A witness wrote, "The horsemen had the best of it from the start. It was a fine race for a few minutes, but soon the riders began to spread out like a fan, and by the time they reached the horizon they were scattered about as far as the eye could see." In a day, the towns of Oklahoma City, Norman, and Guthrie came into existence. In the same manner, millions of acres of additional land was opened up and settled in the following four years.

U.S. Census and Turner's Thesis

After the eleventh U.S. Census was taken in 1890, the superintendent announced that there was no longer a clear line of advancing settlement, and hence no longer a frontier in the continental United States. In his highly influential Frontier Thesis in 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner concluded that the frontier experience was largely over. Turner cited the report as he explained the development of American democracy and national character in terms of the transformations experienced since 1600 by the pioneers as they shed European ways and became more American.[44]

Recent history

World Wars era

At the beginning of the First World War, thousands from the region enlisted in the United States military after the United States declared war on Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

The Dust Bowl was a series of dust storms caused by a massive drought that began in 1930 and lasted until 1941. The effect of the drought combined with the effects of the Great Depression, forced many farmers off the land throughout the Great Plains. The several economic and climatic conditions combined with disastrous results. A lack of rainfall, extremely high temperatures and over-cultivation of farmland produced what was known as the Dust Bowl in several other plains states. Fertile topsoil was blown away in massive dust storms, and several harvests were completely ruined.[45] The experiences of the Dust Bowl, coupled with local bank foreclosures and the general economic effects of the Great Depression resulted in many leaving the region. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, photographs by Dorothea Lange, and songs of Woody Guthrie tales of woe from the era. The negative images of the "Okie" as a sort of rootless migrant laborer living in a near-animal state of scrounging for food greatly offended many Oklahomans. These works often mix the experiences of former sharecroppers of the western American South with those of the exodusters fleeing the fierce dust storms of the High Plains. Although they primarily feature the extremely destitute, the vast majority of the people, both staying in and fleeing the region, suffered great poverty in the Depression years.

Economic stability returned with the U.S. entry into World War II in 1941, when demand for agricultural and industrial products grew as the nation mobilized for war. During the Second World War, states were home to several prisoner of war camps. In addition, several U.S. Army Airfields were constructed at various locations across the region

Contemporary era

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education unanimously declared that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal" and, as such, violate the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees all citizens "equal protection of the laws." Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka explicitly outlawed racial segregation of public education facilities (that is, it was no longer legal to operate separate government-run schools for blacks and whites). The site consists of the Monroe Elementary School, one of the four segregated elementary schools for African American children in Topeka, Kansas (and the adjacent grounds).

During the 1950s and 1960s, intercontinental ballistic missiles (designed to carry a single nuclear warhead) were stationed throughout the region's facilities. They were stored (to be launched from) hardened underground silos. Many facilities were deactivated in the early 1980s.

On November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Many people immediately blamed the conservative environment of Dallas for the act, though the assassin turned out to be a Communist sympathizer recently returned from Moscow.[46]

In 1995 Oklahoma became the scene of an act of terrorism. On April 19, in the Oklahoma City bombing, Timothy McVeigh bombed the Federal Building, killing 168 people, including 19 children. McVeigh, a militia movement sympathizer, sought revenge against the federal government for its handling of the Waco siege in Texas, which had killed 76 people two years before to the day, as well as for the Federal killings at Ruby Ridge in Idaho in 1992.[47]

Frontier Strip in Presidential elections

| Year | Kansas | Nebraska | North Dakota | Oklahoma | South Dakota | Texas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower |

| 1956 | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower | Eisenhower |

| 1960 | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Kennedy |

| 1964 | Johnson | Johnson | Johnson | Johnson | Johnson | Johnson |

| 1968 | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Humphrey |

| 1972 | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon | Nixon |

| 1976 | Ford | Ford | Ford | Ford | Ford | Carter |

| 1980 | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan |

| 1984 | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan | Reagan |

| 1988 | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush |

| 1992 | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush |

| 1996 | Dole | Dole | Dole | Dole | Dole | Dole |

| 2000 | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush |

| 2004 | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush | Bush |

| 2008 | McCain | McCain | McCain | McCain | McCain | McCain |

| 2012 | Romney | Romney | Romney | Romney | Romney | Romney |

| 2016 | Trump | Trump | Trump | Trump | Trump | Trump |

| Year | Kansas | Nebraska | North Dakota | Oklahoma | South Dakota | Texas |

References

- General information

19th century sources

- Marcy, Randolph Barnes. The Prairie and Overland Traveller: A Companion for Emigrants, Traders, Travellers, Hunters, and Soldiers Traversing Great Plains and Prairies. London: S. Low, 1860.

- Dana, C. W., Thomas Hart Benton. The Great West, Or The Garden of the World: Its History, Its Wealth, Its Natural Advantages, and Its Future, Thayer & Eldridge, 1861

- Gilpin, William. Mission of the North American People, Geographical, Social, and Political. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co, 1874.

- Dodge, Richard Irving, William Blackmore, The Plains of the Great West and Their Inhabitants: Being a Description of the Plains, Game, Indians of the Great North American Desert. G. P. Putnam's sons, 1876.

- Dodge, Richard Irving, William Blackmore, Ernest Henry Griset, The Hunting Grounds of the Great West: A Description of the Plains, Game, and Indians of the Great North American Desert. Chatto & Windus, 1877

- Campion, J. S. On the Frontier: Reminiscences of Wild Sports, Personal Adventures, and Strange Scenes. Chapman & Hall, 1878.

20th and 21st century sources

- Parrish, Randall. The Great Plains: The Romance of Western American Exploration, Warfare, and Settlement, 1527-1870. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co, 1907.

- Paxson, Frederic L. The Last American Frontier. New York: Macmillan, 1910.

- Turner, Frederick Jackson. The Frontier in American History. New York: Henry Holt and Co, 1921.

- Smith, Henry Nash, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1950. ISBN 0-674-93955-7

- Slotkin, Richard. Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America. 1960.

- Lamar, Howard, ed. The New Encyclopedia of the American West (1998); this is a revised version of Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West ed. by Howard Lamar. 1977.

- Tompkins, Jane, West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns. 1993.

- Jules David Prown, Nancy K. Anderson, and William Cronon, eds. Discovered Lands, Invented Pasts: Transforming Visions of the American West. 1994.

- Mitchell, Lee Clark, Westerns: Making the Man in Fiction and Film. 1998.

- Slotkin, Richard. The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1800-1890. 1998.

- Wishart, David J. Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 2004. The American Legal Frontier. Page 442 - 443.

- Footnotes

- ↑ Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier In American History.

- ↑ Utley, Robert Marshall. The Indian Frontier of the American West, 1846-1890. Histories of the American frontier. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

- ↑ Paxson, Frederic L. The Last American Frontier. New York: Macmillan, 1910.

- ↑ In later days and with the discovery of gold in the Klondike in 1896, a new frontier was opened up in the vast northern territory. Alaska afterward became known as "the last frontier.".

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau (2000-06-13). "Brief History of the U.S. Census". 200 Years of Census Taking: Population and Housing Questions, 1790-1990. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/maps/pdfs/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

- ↑ Civil War from the Handbook of Texas Online Accessed January 14, 2009

- ↑ Johnson, Andrew (1866-08-20). "Proclamation Declaring the Insurrection at an End". American Historical Documents. President of the United States. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ "Dakota Territory History". Union County Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ "Treaty with the Seminole, 1866". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Volume II, Treaties. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ "Treaty with the Creek, 1866". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Volume II, Treaties. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ Weber (1992), p. 280.

- ↑ Chipman (1992), p. 205.

- ↑ Chipman (1992), pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Weber (1992), p. 291.

- ↑ Manchaca (2001), p. 187.

- ↑ Manchaca (2001), p. 164.

- ↑ Edmondson (2000), p. 61.

- ↑ Manchaca (2001), p. 199.

- ↑ UTSA ITC Education Scrapbook - Texas the Shape and the Name, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Institute of Texan Cultures. 1996-2001, verified 2005-12-30.

- ↑ Edmondson (2000), p. 80.

- ↑ Manchaca (2001), p. 200.

- ↑ Vazquez (1997), p. 68.

- ↑ Vazquez (1997), p. 71.

- ↑ Vazquez (1997), p. 72.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 12.

- ↑ Barr (1990), p. 64.

- ↑ Vazquez (1997), p. 74.

- ↑ Todish et al. (1998), p. 69.

- ↑ Todish et al. (1998), p. 70.

- ↑ Vazquez (1997), p. 77.

- ↑ Cotton Culture from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ Terry G. Jordan, German seed in Texas soil: Immigrant farmers in nineteenth-century Texas (1966).

- ↑ Theodore G. Gish, and Richard Spuler, eds., Eagle in the new world: German immigration to Texas and America (Texas A & M U. Press, 1986)

- ↑ "Czechs", Handbook of Texas Online, accessed July 28, 2008.

- ↑ Randolph B. Campbell, An empire for slavery: The peculiar institution in Texas, 1821-1865 (LSU Press, 1991)

- ↑ Brad R. Clampit, ."The Breakup: The Collapse of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Army in Texas, 1865", Southwest Historical Quarterly, Vol CVIII, No 4. April, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.txstate.edu/freemanranch/about/History/Early-Anglo-American-Settlement-through-Civil-War-.html

- ↑ https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/mzr01

- ↑ http://texasourtexas.texaspbs.org/the-eras-of-texas/cotton-cattle-railroads/

- ↑ Joseph Warren Keifer (2009) [1900]. Slavery and Four Years of War. p. 109.

- ↑ Richard White (1991). "It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own": A New History of the American West. U. of Oklahoma Press. p. 142.

- ↑ Horan & Sann, Pictorial History of the Wild West, Bonanza Books, New York, 1964, p. 52

- ↑ Ray Allen Billington, ed., The Frontier Thesis: Valid Interpretation of American History? (1966)

- ↑ "Drought in the Dust Bowl Years". National Drought Mitigation Center. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ Sean P. Cunningham; Sean P. P. Cunningham (2010). Cowboy Conservatism: Texas and the Rise of the Modern Right. University Press of Kentucky. p. 94.

- ↑ Harvey W. Kushner (2003). Encyclopedia of Terrorism. SAGE. p. 41.

External links

- "New Perspectives on 'The West'". The West Film Project, WETA, 2001.

- Dodge City, Kansas 'Cowboy Capital'

- Fort Dodge, KS History by Ida Ellen Rath, 1964 w/ photos

- Old West Kansas

- WWW-VL: American West History

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory