Gandalf

| Gandalf | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien's legendarium character | |

| Aliases | |

| Race | Maia (subset Istari) |

| Book(s) |

The Hobbit (1937) The Fellowship of the Ring (1954) The Two Towers (1954) The Return of the King (1955) The Silmarillion (1977) Unfinished Tales (1980) |

Gandalf /ˈɡændɑːlf/ is a fictional character and one of the protagonists in J. R. R. Tolkien's novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. He is a wizard, member of the Istari order, as well as leader of the Fellowship of the Ring and the army of the West. In The Lord of the Rings, he is initially known as Gandalf the Grey, but returns from death as Gandalf the White.

Characteristics

Tolkien discusses Gandalf in his essay on the Istari, which appears in the work Unfinished Tales. He describes Gandalf as the last of the wizards to appear in Middle-earth, one who: "seemed the least, less tall than the others, and in looks more aged, grey-haired and grey-clad, and leaning on a staff". Yet the Elf Círdan who met him on arrival nevertheless considered him "the greatest spirit and the wisest" and gave him the elven Ring of power called Narya, the Ring of Fire, containing a "red" stone for his aid and comfort. Tolkien explicitly links Gandalf to the element Fire later in the same essay:

Warm and eager was his spirit (and it was enhanced by the ring Narya), for he was the Enemy of Sauron, opposing the fire that devours and wastes with the fire that kindles, and succours in wanhope and distress; but his joy, and his swift wrath, were veiled in garments grey as ash, so that only those that knew him well glimpsed the flame that was within. Merry he could be, and kindly to the young and simple, yet quick at times to sharp speech and the rebuking of folly; but he was not proud, and sought neither power nor praise... Mostly he journeyed tirelessly on foot, leaning on a staff, and so he was called among Men of the North Gandalf 'the Elf of the Wand'. For they deemed him (though in error) to be of Elven-kind, since he would at times work wonders among them, loving especially the beauty of fire; and yet such marvels he wrought mostly for mirth and delight, and desired not that any should hold him in awe or take his counsels out of fear. ... Yet it is said that in the ending of the task for which he came he suffered greatly, and was slain, and being sent back from death for a brief while was clothed then in white, and became a radiant flame (yet veiled still save in great need).[2]

Internal biography

As one of the Maiar, Gandalf would have participated in the Music of the Ainur at the creation of the world. However he does not attain any prominence until the Valar settle in Valinor.

Valinor

In Valinor, Gandalf was known as Olórin.[1] As recounted in the "Valaquenta" in The Silmarillion,[3] he was one of the Maiar of Valinor, specifically, of the people of the Vala Manwë; and was said to be the wisest of the Maiar. He was also closely associated with two other Valar: Irmo, in whose gardens he lived, and Nienna, the patron of mercy, who gave him tutelage. When the Valar decided to send the order of the Wizards (Istari) to Middle-earth in order to counsel and assist all those who opposed Sauron, Olórin was proposed by Manwë. Olórin initially begged to be excused as he feared Sauron and lacked the strength to face him, but Manwë replied that that was all the more reason for him to go.[4]

As one of the Maiar, Gandalf was not a mortal Man but an angelic being who had taken human form. As one of those spirits, Olórin was in service to the Creator (Eru Ilúvatar) and the Creator's 'Secret Fire'. Along with the other Maiar who entered into the world as the five Wizards, he took on the specific form of an aged old man as a sign of his humility. The role of the wizards was to advise and counsel but never to attempt to match Sauron's strength with his own, and hopefully the kings and lords of Middle-earth would be more receptive to the advice of a humble old man than a more glorious form giving them direct commands.

Middle-earth

Gandalf the Grey was the last of the Istari landing in the Havens of Mithlond. He seemed the oldest and least in stature of them, but Círdan the Shipwright felt that he had the highest inner greatness on their first meeting in the Havens, and gave him Narya, the Ring of Fire. Saruman, the chief Wizard, later learned of the gift and resented it. Gandalf hid the ring well, and it was not widely known until he left with the other ring-bearers at the end of the Third Age that he, and not Círdan, was the holder of the third of the Elven-rings.

Gandalf's relationship with Saruman, the head of their Order, was strained. The Wizards were commanded to aid Men, Elves, and Dwarves, but only through counsel; it was forbidden to use force to dominate them — an injunction that Saruman increasingly disregarded.

The White Council

In "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age" (in The Silmarillion) and "The Istari" (in Unfinished Tales), Tolkien fleshes out the background and the history briefly tabulated by date in Appendix B of The Lord of the Rings. Gandalf suspected early on that the Necromancer of Dol Guldur was not a Nazgûl but Sauron himself. He went to Dol Guldur (in T.A. 2063[5]) to discover the truth, but the Necromancer withdrew before him. The Necromancer returned to Dol Guldur with greater force in T.A. 2460,[5] and the White Council was formed in response (T.A. 2463[5]). Galadriel had hoped Gandalf would lead the Council, but Gandalf refused, declining to be bound by any but the Valar who sent him. Saruman was chosen instead, as being most knowledgeable about Sauron's work in the Second Age.

Gandalf returned to Dol Guldur in T.A. 2850[5] "at great peril" and learned that the Necromancer was indeed Sauron returned. (This is when Gandalf found Thráin II imprisoned in Dol Guldur and recovered Thrór's map and the key to Erebor before Thráin died.[5]) The following year[5] the White Council was summoned, and Gandalf urged that Sauron be driven out. Saruman, however, reassured the Council that Sauron's evident effort to find the One Ring (a necessary component of his resurgence) would fail, as the Ring would long since have been carried by the river Anduin to the Sea; and the matter was allowed to rest. But at this time Saruman himself began actively seeking the Ring near the Gladden Fields where Isildur had been killed, not far from Dol Guldur.

The Quest of Erebor

"The Quest of Erebor" in Unfinished Tales elaborates upon the story behind The Hobbit. It tells of a chance meeting between Gandalf and Thorin Oakenshield, a Dwarf-king in exile, in the inn of the Prancing Pony in Bree. Gandalf had for some time foreseen the coming war with Sauron, and knew that the North was especially vulnerable. If Rivendell were to be attacked, the dragon Smaug could cause great devastation. He persuaded Thorin that he could help him regain his lost territory of Erebor from Smaug, and so the quest was born.

In T.A. 2941,[5] Gandalf arranged (and frequently accompanied) a band of 13 dwarves and the hobbit Bilbo Baggins to reclaim from Smaug the Dwarves' lost treasure in Erebor. To the quest, Gandalf contributed a map and key to Erebor. It was on this Quest of Erebor that Gandalf found his sword, Glamdring, in a troll's treasure hoard.

After escaping from the Misty Mountains pursued by Goblins and Wargs, the party was carried to safety by the Great Eagles. Gandalf then persuaded Beorn—who did not like uninvited guests or dwarves—to house and provision the company for the trip through Mirkwood.

Gandalf left the company before they entered Mirkwood, saying that he had pressing business to attend to. He turned up again, however, before the walls of Erebor disguised as an old man, revealing himself when it seemed the Men of Esgaroth and the Mirkwood Elves would fight Thorin and the Dwarves over Smaug's treasure. The Battle of the Five Armies ensued when hosts of Goblins and Wargs attacked all three parties. After the battle, Gandalf accompanied Bilbo back to the Shire, revealing at Rivendell what his pressing business had been: Gandalf had once again urged the Council to evict Sauron, since quite evidently Sauron did not require the One Ring to continue to attract evil to Mirkwood. Then, in an event only briefly described (in The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings), the Council "put forth its power" and drove Sauron from Dol Guldur. Sauron, however, had anticipated this and withdrew as a feint, only to reappear in Mordor.

Prelude to the War of the Ring

As explained in The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf spent the years between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings travelling Middle-earth in search of information on Sauron's resurgence and Bilbo's mysterious ring, spurred particularly by Bilbo's initial misleading story of how he had obtained it as a "present" from Gollum. During this period he befriended Aragorn and first became suspicious of Saruman. He spent as much time as he could in the Shire, strengthening his friendship with Bilbo and Frodo, Bilbo's heir.

He returned to the Shire for Bilbo's "eleventy-first" (111th) birthday party in T.A. 3001, bringing many fireworks for the occasion. After Bilbo, as a prank on his guests, put on the Ring and disappeared, Gandalf strongly encouraged his old friend to leave the Ring to Frodo, as they had planned. Bilbo became hostile and accused Gandalf of trying to steal the Ring—which he called "my precious", much as Gollum had done. (Isildur, who earlier possessed the ring and was destroyed by it, had written that "it is precious to me").[6] Alarmed, Gandalf impressed on Bilbo the foolishness of this accusation. Coming to his senses, Bilbo admitted that the Ring had been troubling him, and leaving it behind for Frodo, he departed for Rivendell. Though Bilbo would never be entirely free of the desire for the Ring, he was the first of its bearers to give it up willingly.

Over the next 17 years, Gandalf travelled extensively, searching for answers on the Ring. He found some answers in Isildur's scroll, in the archives of Minas Tirith. But he also wanted to interview Gollum, who had borne the Ring for many years. Gandalf searched long and widely for Gollum, and often had the assistance of Aragorn. Aragorn eventually succeeded, and Gandalf questioned Gollum, threatening him with fire when he proved unwilling to speak. Gandalf learned finally that Sauron had forced Gollum under torture in Barad-dûr to tell what he knew of the Ring. This reinforced Gandalf's growing suspicion that Bilbo's ring was the One Ring.

The Fellowship of the Ring

Returning to the Shire, in T.A. 3018, Gandalf confirmed his suspicions by throwing the Ring into Frodo's hearth-fire and reading the writing that appeared on the Ring's surface. He told Frodo the full history of the Ring, and urged him to take the Ring to Rivendell; for he would be in grave danger if he stayed in the Shire. Gandalf said he would attempt to return for Frodo's 50th birthday party, in order to accompany him on the road thereafter; and that meanwhile Frodo should arrange to leave quietly, as the servants of Sauron would be searching for him.

Outside the Shire, Gandalf encountered Radagast the Brown, another of the Istari, who brought the news that the Nazgûl had ridden forth and crossed the River Anduin—and a request from Saruman that Gandalf come to Isengard. Gandalf left a letter to Frodo (urging his immediate departure) with Barliman Butterbur at the inn in Bree, and headed towards Isengard. There Saruman revealed his true colours, urging Gandalf to help him obtain the Ring for his own use. Gandalf refused, and Saruman imprisoned him at the top of the tower of Orthanc. Eventually Gandalf was rescued by Gwaihir the Eagle.

Gwaihir set Gandalf down in Rohan, where Gandalf appealed to King Théoden for a horse. Théoden, under the malign influence of Gríma Wormtongue, Saruman's spy, told Gandalf to take any horse he pleased, but to leave quickly. It was then that Gandalf met the great horse Shadowfax, one of the mearas, who would be his mount and companion for most of the rest of the war. Gandalf pursued the horse for two days[5] before Shadowfax permitted Gandalf to ride him. Gandalf then rode hard for the Shire, but did not reach it until Frodo had already set out. Knowing that Frodo and his companions would be heading for Rivendell, Gandalf began to make his own way there. He learned at Bree that the Hobbits had fallen in with Aragorn. He faced the Nazgûl at Weathertop but escaped after an all-night battle, drawing four of them northward. Frodo, Aragorn and company faced the remaining five on Weathertop a few nights later. Gandalf reached Rivendell just before Frodo's arrival.

In Rivendell, Gandalf helped Elrond drive off the Nazgûl pursuing Frodo and played a great part in the following council as the only person who knew the full history of the Ring. He also revealed that Saruman had betrayed them and was in league with Sauron. When it was decided that the Ring had to be destroyed, Gandalf volunteered to accompany Frodo—now the Ring-bearer—in his quest. He also persuaded Elrond to let Frodo's cousins Merry and Pippin join the Fellowship.

Taking charge of the Fellowship (comprising nine representatives of the free peoples of Middle-earth, "set against the Nine Riders"), Gandalf and Aragorn led the Hobbits and their companions south. After an unsuccessful attempt to cross Mount Caradhras in winter, they crossed under the mountains through the Mines of Moria, though only Gimli the Dwarf was enthusiastic about that route. In Moria, they discovered that the Dwarf colony established there earlier had been overrun by Orcs. The Fellowship fought with the Orcs and Trolls of Moria and escaped them.

At the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, they encountered "Durin's Bane," a fearsome Balrog from ancient times. Gandalf faced the Balrog to enable the others to escape. After a brief exchange of blows, Gandalf broke the bridge beneath the Balrog with his staff. As the Balrog fell, it wrapped its whip around Gandalf's legs, dragging him over the edge. As his friends looked on in horror, Gandalf fell into the abyss, crying "Fly, you fools!" as he went.

After a long fall, Gandalf and the Balrog crashed into a deep subterranean lake far under Moria. Gandalf pursued the Balrog through the tunnels for eight days until they climbed to the peak of Zirakzigil. Here they fought for two days and nights. In the end, the Balrog was defeated and cast down onto the mountainside. Gandalf himself died shortly afterwards, and his body lay on the peak while his spirit travelled "out of thought and time".

Gandalf the White

Gandalf was eventually "sent back"[7] as Gandalf the White, and returned to life on the mountain top. Gwaihir, lord of eagles, carried him to Lórien, where he was healed of his injuries and re-clothed in white robes by Galadriel. He travelled to Fangorn Forest, where he encountered Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas (who were tracking Merry and Pippin). They mistook him for Saruman, but he stopped their attacks and revealed himself.

They travelled to Rohan, where Gandalf found that Théoden had been further weakened by Wormtongue's influence. He broke Wormtongue's hold over Théoden, and convinced the king to join in the fight against Sauron. Gandalf then set off to gather Erkenbrand of the Westfold and his warriors to assist Théoden in the coming battle with Saruman. Gandalf arrived just in time to shatter Saruman's attack on Helm's Deep. After the ensuing battle, Gandalf and the king rode to Isengard, which in the interim had itself been attacked and conquered by Treebeard and the Ents, along with Merry and Pippin. Gandalf broke Saruman's staff and expelled him from the White Council and the Order of Wizards, and assumed Saruman's place as head of both. Wormtongue made an indecisive attempt to kill Gandalf or Saruman with the palantír of Orthanc, but missed both. Pippin retrieved the palantír, but Gandalf quickly appropriated it. After the group left Isengard, Pippin took the palantír from a sleeping Gandalf, looked into it, and came face to face with Sauron himself. Gandalf then took the chastened Pippin with him to Minas Tirith to keep the young hobbit out of further trouble.

Gandalf arrived in time to help order the defences of Minas Tirith. His presence was resented by Denethor, the Steward of Gondor; but after Denethor's son Faramir was gravely wounded in battle, Denethor sank into despair and madness. Together with Prince Imrahil of Dol Amroth, Gandalf led the defenders during the siege of the city. When the forces of Mordor finally broke the main gate, Gandalf alone on Shadowfax confronted the Witch-king of Angmar, Lord of the Nazgûl. But at that moment the Rohirrim arrived, compelling the Witch-king to withdraw and engage them. Gandalf would have ridden to their aid, but he too was suddenly required elsewhere—to save Faramir from Denethor, who sought in desperation to burn himself and his son on a funeral pyre in Rath Dínen.

Aragorn and Gandalf then led the final campaign against Sauron's forces at the Black Gate, in an effort to distract the Dark Lord's attention from Frodo Baggins and Sam Gamgee, who were at the same moment scaling Mount Doom to destroy the One Ring. In a parley before the battle, Gandalf and the other leaders of the West met the Mouth of Sauron, who showed them Frodo's mithril shirt and other items from the Hobbits' equipment. But Gandalf rejected Mordor's terms of surrender, and the forces of the West faced the full might of Sauron's armies, until the Ring was destroyed in Mount Doom. Gandalf led the Eagles to rescue Frodo and Sam from the erupting mountain.

After the war, Gandalf crowned Aragorn as King Elessar, and helped him find a sapling of the White Tree of Gondor. He accompanied the Hobbits back to the borders of the Shire, before leaving to visit Tom Bombadil.

Two years later, Gandalf—who by now had spent about 2,000 years in Middle-earth[5]—departed with Frodo, Bilbo, Galadriel, and Elrond across the sea to the Undying Lands. It was only then that his possession of Narya, one of the Three Elven Rings, became generally known.

Concept and creation

Humphrey Carpenter in his 1977 biography relates that Tolkien owned a postcard entitled Der Berggeist ("the mountain spirit"), and on the paper cover in which he kept it, he wrote "the origin of Gandalf". The postcard reproduces a painting of a bearded figure, sitting on a rock under a pine tree in a mountainous setting. He wears a wide-brimmed round hat and a long red cloak, and a white fawn is nuzzling his upturned hands.

Carpenter said that Tolkien recalled buying the postcard during his holiday in Switzerland in 1911. Manfred Zimmerman,[8] however, discovered that the painting was by German artist Josef Madlener and dates to the mid-1920s. Carpenter acknowledged that Tolkien was probably mistaken about the origin of the postcard.

The original painting was auctioned at Sotheby's in London on 12 July 2005 for £84,000.[9] The previous owner had been given the painting by Madlener in the 1940s and recalled that Madlener said the mountains in the background were the Torri del Vaiolet peaks in the Dolomites.[8]

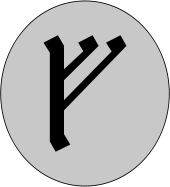

When writing The Hobbit in the early 1930s Tolkien gave the name Gandalf to the leader of the Dwarves, the character later called Thorin Oakenshield. The name is taken from the same source as all the other Dwarf names (save Balin) in The Hobbit: the "Catalogue of Dwarves" in the Völuspá.[10] The Old Norse name Gandalfr incorporates the words gandr meaning "wand", "staff" or (especially in compounds) "magic" and álfr "elf". The name Gandalf is found in at least one more place in Norse myth, in the semi-historical Heimskringla, which briefly describes Gandalf Alfgeirsson, a legendary Norse king from Eastern Norway and rival of Halfdan the Black.[11]

.jpg)

The name "Gandolf" occurs as a character in William Morris' 1896 fantasy novel The Well at the World's End. Morris' book is a multi-part 'magical journey' involving elves, dwarves and kings in a pseudo-medieval landscape which is known to have deeply influenced Tolkien.

The wizard that became Gandalf was originally named Bladorthin.[12][13] Tolkien later assigned this name to an ancient king who had ordered some spears from the dwarves.[14]

Tolkien came to regret his ad hoc use of Old Norse name, referring to a "rabble of eddaic-named dwarves, ... invented in an idle hour" in 1937.[15] But the decision to use Old Norse names came to have far-reaching consequences in the composition of The Lord of the Rings; in 1942, Tolkien decided that the work was to be a purported translation from the fictional language of Westron, and in the English translation Old Norse names were taken to represent names in the language of Dale.[16] Gandalf, in this setting, is thus a representation in English (anglicised from Old Norse) of the name the dwarves of Dale had given to Olórin in the language they used "externally" in their daily affairs, while Tharkûn is the (untranslated) name, presumably of the same meaning, that the dwarves gave him in their native Khuzdul language. Tolkien explains this in his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings (1967) to prospective translators.

Throughout the early drafts, and through to the first edition of The Hobbit Bladorthin/Gandalf is described as being a "little old man", distinct from a dwarf, but not of the full human stature that would later be described in The Lord of the Rings. Even in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf was not tall; shorter, for example, than Elrond[17] or the other wizards.[18]

Gandalf's role and importance was substantially increased in the conception of The Lord of the Rings, and in a letter of 1954, Tolkien refers to Gandalf as an "angel incarnate".[19] In the same letter Tolkien states he was given the form of an old man in order to limit his powers on Earth. Both in 1965 and 1971 Tolkien again refers to Gandalf as an angelic being.[20][21]

In a letter of 1946 Tolkien stated that he thought of Gandalf as an "Odinic wanderer".[22] Other commentators have also compared Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his "Wanderer" guise—an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff.[23]

Adaptations

In the BBC Radio dramatizations, Gandalf has been voiced by Norman Shelley in The Lord of the Rings (1955–1956), Heron Carvic in The Hobbit (1968), Bernard Mayes in The Lord of the Rings (1979) and Sir Michael Hordern in The Lord of the Rings (1981).

John Huston voiced Gandalf in the animated films The Hobbit (1977) and The Return of the King (1980) produced by Rankin/Bass. William Squire voiced Gandalf in the animated film The Lord of the Rings (1978) directed by Ralph Bakshi. Gandalf was portrayed by Vesa Vierikko in the Finnish television miniseries Hobitit (1993).

Sir Ian McKellen portrayed Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings film series (2001–2003) directed by Peter Jackson, after Sean Connery and Patrick Stewart both turned down the role.[24][25] The make-up and costumes were based on designs by John Howe and Alan Lee. According to Jackson, McKellen based his performance as Gandalf on Tolkien himself:

We listened to audio recordings of Tolkien reading excerpts from Lord of the Rings. We watched some BBC interviews with him — there's a few interviews with Tolkien — and Ian based his performance on an impersonation of Tolkien. He's literally basing Gandalf on Tolkien. He sounds the same, he uses the speech patterns and his mannerisms are born out of the same roughness from the footage of Tolkien. So, Tolkien would recognize himself in Ian's performance.[26]

For the first film, McKellen was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[27] He more recently reprised the role in The Hobbit film series (2012–2014), claiming that he enjoyed playing Gandalf the Grey more than Gandalf the White.[28][29] McKellen has also provided the voice of Gandalf for multiple video games based on the films, including The Two Towers and The Return of the King.

Charles Picard portrayed Gandalf in the 1999 stage production of The Two Towers at Chicago's Lifeline Theatre. Tom Stiver portrayed Gandalf in the early 2000s stage productions of The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers and The Return of the King for Clear Stage Cincinnati. Brent Carver portrayed Gandalf in the 2006 musical production The Lord of the Rings, which opened in Toronto.[30]

Gandalf appears in The Lego Movie voiced by Todd Hanson. He is among the Master Builders that meet in Cloud Cuckoo Land. Vitruvius often mixes him up with Albus Dumbledore, much to the chagrin of the two wizards. Gandalf is also a playable character in The Lego Movie Videogame: in story mode he and a Magician help Emmet fight Lord Business's giant robot by providing his construction mech with debris to throw at it. Gandalf appears in the video game Lego Dimensions and is voiced by Tom Kane (who has voiced another iconic Ian McKellen role, Magneto). Gandalf is one of the three main characters (with Batman and Wyldstyle) and works with them to rescue the kidnapped Frodo and the One Ring.[31]

Reception and legacy

Gandalf was chosen by Mary Hoffman as one of her favourite fictional characters, saying he was "the best white wizard in fiction".[32]

Ian McKellen received widespread acclaim for his performance as Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings films; particularly in The Fellowship of the Ring, for which he received both a Screen Actors Guild Award and Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actor, and an Academy Award nomination under the same category (making him the only individual cast member of the films to be nominated for an Oscar). In addition, Empire named Gandalf, as portrayed by McKellen, the 28th greatest film character of all time.[33]

See also

Notes

^a) Meaning "Grey Pilgrim"

References

- 1 2 "Olórin I was in my youth in the West that is forgotten", The Two Towers, "The Window on the West", page 353.

- ↑ Unfinished Tales, "The Istari", p 390–391.

- ↑ The Silmarillion, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Unfinished Tales, Part Four, "The Istari", p. 393.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 The Return of the King, Appendix B.

- ↑ The Fellowship of the Ring, "The Council of Elrond".

- ↑ In Letters, #156, pp 202–3, Tolkien clearly implies that the 'Authority' that sent Gandalf back was above the Valar (who are bound by Arda's space and time, while Gandalf went beyond time). He clearly intends this as an example of Eru intervening to change the course of the world.

- 1 2 Manfred Zimmerman, The Origin of Gandalf and Josef Madlener, Mythlore 34 (1983).

- ↑ Sotheby's

- ↑ Solopova, Elizabeth (2009), Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J.R.R. Tolkien's Fiction, New York City: North Landing Books, p. 20, ISBN 0-9816607-1-1

- ↑ "Halfdan the Black Saga (Ch. 1. Halfdan Fights Gandalf and Sigtryg) in Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla: A History of the Norse Kings, transl. Samuel Laing (Norroena Society, London, 1907)". Omacl.org. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

The same autumn he went with an army to Vingulmark against King Gandalf. They had many battles, and sometimes one, sometimes the other gained the victory; but at last they agreed that Halfdan should have half of Vingulmark, as his father Gudrod had had it before.

- ↑ Douglas Anderson, The Annotated Hobbit, "Inside Information", note 9, p. 287.

- ↑ John Rateliff, Mr. Baggins, "Introduction", p. ix (and many other references throughout the book).

- ↑ The Hobbit, "Inside Information".

- ↑ The Return of the Shadow, p. 452.

- ↑ Tom Shippey. "Tolkien and Iceland: The Philology of Envy". Nordals.hi.is. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

We know that Tolkien had great difficulty in getting his story going. In my opinion, he did not break through until, on February 9, 1942, he settled the issue of languages

- ↑ The Fellowship of the Ring, "Many Meetings".

- ↑ Unfinished Tales, "The Istari", p. 389.

- ↑ Letters, no. 156.

- ↑ Letters, no. 268.

- ↑ Letters, no. 325.

- ↑ Letters, no. 107.

- ↑ Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1997). An investigation of the Teutonic god Óðinn; and a study of his relationship to J. R.R. Tolkien’s character, Gandalf (Thesis). University of New England. Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-8020-3806-9.

- ↑ Daniel Saney (1 August 2005). "'Idiots' force Connery to quit acting". Digital Spy. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "New York Con Reports, Pictures and Video". TrekMovie. 9 March 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ↑ "Peter Jackson, 'The Hobbit' Director, On Returning To Middle-Earth & The Polarizing 48 FPS Format". Mike Ryan. The Huffington Post. 6 December 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Brian Sibley (2006). "Ring-Master". Peter Jackson: A Film-maker's Journey. London: Harpercollins. pp. 445–519. ISBN 0-00-717558-2.

- ↑ "Ian McKellen as Gandalf in The Hobbit". McKellen. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ↑ Jones, Kenneth (2005-07-25). "Precious News! Tony Award Winner Will Play Gandalf in Lord of the Rings Musical; Cast Announced". playbill.com. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ↑ Lang, Derrick (2015-04-09). "Awesome! 'Lego Dimensions' combining bricks and franchises". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ↑ "The 100 favourite fictional characters... as chosen by 100 literary luminaries". The Independent. 3 March 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time: 28. Gandalf". Empire. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gandalf. |

- Gandalf at the Internet Movie Database

- "Gandalf". Tolkien Gateway.

- "Gandalf". Tolkien-Online.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007.

- Gandalf at lotr.wikia.com

- Gandalf at fansite: TheOneRing.net

- Gandalf at the Encyclopedia of Arda

- "The painting from which Tolkien drew inspiration for Gandalf". Tolkien Society. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013.