Geography of Chile

| Continent | South America |

|---|---|

| Region |

Southern Cone Southern Cone |

| Coordinates | 30°00'S 70°00' W |

| Area | Ranked 38th |

| • Total | 756,102 km2 (291,933 sq mi) |

| • Land | 98.4% |

| • Water | 1.6% |

| Coastline | 6,435 km (3,999 mi) |

| Borders |

Total land borders: 7,801 km (4,847 mi) Argentina: 6,691 km (4,158 mi) Bolivia: 942 km (585 mi) Peru: 168 km (104 mi) |

| Highest point |

Ojos del Salado in Andes of Atacama Region 6,893 m (22,615 ft) |

| Lowest point | Pacific Ocean, 0 m |

| Longest river | Loa River, 440 km (273 mi) |

| Largest lake | General Carrera Lake |

The geography of Chile is extremely diverse as the country extends from a latitude of 17° South to Cape Horn at 56° (if Chilean claims on Antarctica are included Chile would extend to the South Pole) and from the ocean on the west to Andes on the east. Chile is situated in southern South America, bordering the South Pacific Ocean and a small part of the South Atlantic Ocean. Chile's territorial shape is among the world's most unusual. From north to south, Chile extends 4,270 km (2,653 mi), and yet it only averages 177 km (110 mi) east to west. On a map, it looks like a long ribbon reaching from the middle of South America's west coast straight down to the southern tip of the continent, where it curves slightly eastward. Diego Ramírez Islands and Cape Horn, the southernmost points in the Americas, where the Pacific and Atlantic oceans turbulently meet, are Chilean territory. Chile's northern neighbors are Peru and Bolivia, and its border with Argentina to the east, at 5,150 km (3,200 mi), is the world's third longest.

A long, narrow nation

.jpg)

The northern two-thirds of Chile lie on top of the telluric Nazca Plate, which, moving eastward about ten centimeters a year, is forcing its way under the continental plate of South America. This movement has resulted in the formation of the Peru–Chile Trench, which lies beyond a narrow band of coastal waters off the northern two-thirds of the country. The trench is about 150 km (93 mi) wide and averages about 5,000 m (16,404 ft) in depth. At its deepest point, just north of the port of Antofagasta, it plunges to 8,066 m (26,463 ft). Although the ocean's surface obscures this fact, most of Chile lies at the edge of a profound precipice.

The same telluric displacements that created the Peru-Chile Trench make the country highly prone to earthquakes. During the twentieth century, Chile has been struck by twenty-eight major earthquakes, all with a force greater than 6.9 on the Richter scale. The strongest of these occurred in 2010 (registering an estimated 8.8 on the Richter scale) and in Valdivia 1960 (reaching 9.5). This latter earthquake occurred on May 22, the day after another major quake measuring 7.25 on the Richter scale, and covered an extensive section of south-central Chile. It caused a tsunami that decimated several fishing villages in the south and raised or lowered sections of the coast as much as two meters. The clash between the Earth's surface plates has also generated the Andes, a geologically young mountain range that, in Chilean territory alone, includes about 620 volcanoes, many of them active. Almost sixty of these had erupted in the twentieth century by the early 1990s. More than half of Chile's land surface is volcanic in origin.

About 80 percent of the land in Chile is made up of mountains of some form or other. Most Chileans live near or on these mountains. The majestically snowcapped Andes and their precordillera elevations provide an ever-present backdrop to much of the scenery, but there are other, albeit less formidable, mountains as well. Although they seemingly can appear anywhere, the non-Andean mountains usually form part of transverse and coastal ranges. The former, located most characteristically in the near north and the far north natural regions, extend with various shapes from the Andes to the ocean, creating valleys with an east-west direction. The latter are evident mainly in the center of the country and create what is commonly called the Central Valley (Valle Central) between them and the Andes. In the far south, the Central Valley runs into the ocean's waters. At this location, the higher elevations of the coastal range facing the Andes become a multiplicity of islands, forming an intricate labyrinth of channels and fjords that have been an enduring challenge to maritime navigators.

Much of Chile's coastline is rugged, with surf that seems to explode against the rocks lying at the feet of high bluffs. This collision of land and sea gives way every so often to lovely beaches of various lengths, some of them encased by the bluffs. The Humboldt Current, which originates northwest of the Antarctic Peninsula (which juts into the Bellingshausen Sea) and runs the full length of the Chilean coast, makes the water frigid. Swimming at Chile's popular beaches in the central part of the country, where the water gets no warmer than 15 °C (59 °F) in the summer, requires more than a bit of fortitude.

Chilean territory extends as far west as Polynesia. The best known of Chile's Pacific Islands is Easter Island (Isla de Pascua, also known by its Polynesian name of Rapa Nui), with a population of 2,800 people. Located 3,600 km (2,237 mi) west of Chile's mainland port of Caldera, just below the Tropic of Capricorn, Easter Island provides Chile a gateway to the Pacific. It is noted for its 867 monoliths (moais), which are huge (up to twenty meters high) and mysterious, expressionless faces sculpted of volcanic stone. The Juan Fernández Islands, located 587 km (365 mi) west of Valparaíso, are the locale of a small fishing settlement. They are famous for their lobster and the fact that one of the islands, Robinson Crusoe Island, is where Alexander Selkirk, the inspiration for Daniel Defoe's novel, was marooned for about four years.

Natural regions

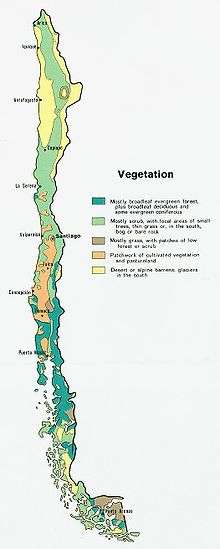

Since Chile extends from a point about 625 km (388 mi) north of the Tropic of Capricorn to a point hardly more than 1,400 km (870 mi) north of the Antarctic Circle, a broad selection of the Earth's climates can be found in this country. Therefore, geographically, the country can be divided into many different parts. It is usually divided by geographers into five regions: the far north, the near north, central Chile, the south, and the far south. Each has its own characteristic vegetation, fauna, climate, and, despite the omnipresence of both the Andes and the Pacific, its own distinct topography.

The Far North

The far north (Norte Grande), which extends from the Peruvian border to about 27° south latitude, a line roughly paralleled to the Copiapó River, is extremely arid. It mainly contains the Atacama Desert, one of the driest areas in the world. In certain areas, this desert does not register any rainfall at all. Geographically, the aridity can be explained by the following reasons:

- The desert is located on the leeward side of the Chilean Coast Range, so little moisture from the Pacific Ocean can reach the desert.

- The Andes is so high that it blocks convective clouds, which may bring precipitation, formed above the Amazon Basin from entering the desert from the east.

- An inversion layer is created by the cold Humboldt current and the South Pacific High.

Average monthly temperatures range at sea level between about 20.5 °C (68.9 °F) during the summer and about 14 °C (57.2 °F) during the winter. Most of the population lives in the coastal area, where the temperatures are more moderate and the humidity higher. Contrary to the image of monochrome barrenness that most people associate with deserts, the landscape is spectacular, with its crisscrossing hills and mountains of all shapes and sizes, each with a unique hue depending on its mineral composition, its distance from the observer, and the time of day.

In the far north, the land generally rises vertically from the ocean, sometimes to elevations well over 1,000 m (3,281 ft). The Cordillera Domeyko in the north runs along the coast parallel to the Andes. This topography generates coastal microclimates because the fog that frequently forms over the cold ocean waters, as well as any low clouds, is trapped by the high bluffs. This airborne moisture condenses in the spines and leaves of the vegetation, droplets that fall to the ground and irrigate the plants' roots. Beyond the coastal bluffs, there is an area of rolling hills that encompasses the driest desert land; this area ends to the east with the Andes towering over it. The edges of the desert in some sections have subterranean aquifers that have permitted the development of forests made up mainly of tamarugos, spiny trees native to the area that grow to a height of about twenty-five meters. Most of those forests were cut down to fuel the fires of the many foundries established since colonial times to exploit the abundant deposits of copper, silver, and nitrate found in the area. The result was the creation of even drier surface conditions.

The far north is the only part of the country in which there is a large section of the Andean (plateau). During summer the area receives considerable rainfall in what is commonly known as the "Bolivian winter,"[1] forming shallow lakes of mostly saline waters (Salar de Llamara, Salar des Miraje, Salar de Atacama)[2] that are home to a number of bird species, including the Chilean flamingo. Some of the water from the plateau trickles down the Andes in the form of narrow rivers, many of which form oases before being lost to evaporation or absorption into the desert sands, salt beds, and aquifers. However, some rivers do manage to reach the Pacific, including the Loa River, whose U-shaped course across the desert makes it Chile's longest river. The water rights for one of the rivers, the Lauca River, remain a source of dispute between Bolivia and Chile. These narrow rivers have carved fertile valleys in which exuberant vegetation creates a stark contrast to the bone-dry hills. In such areas, roads usually are built halfway up the arid elevations in order to maximize the intensive agricultural use of the irrigated land. They offer spectacular panoramic vistas, along with the harrowing experience of driving along the edges of cliffs.

In the far north, the kinds of fruits that grow well in the arid tropics thrive, and all kinds of vegetables can be grown year-round. However, the region's main economic foundation is its great mineral wealth. For instance, Chuquicamata, the world's largest open-pit copper mine, is located in the far north. Since the early 1970s, the fishing industry has also developed enormously in the main ports of the area, most notably Iquique and Antofagasta.

The Near North

The near north (Norte Chico) extends from the Copiapó River to about 32° south latitude, or just north of Santiago. It is a semiarid region whose central area receives an average of about 25 mm (0.98 in) of rain during each of the four winter months, with trace amounts the rest of the year. The near north is also subject to droughts. The temperatures are moderate, with an average of 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) during the summer and about 12 °C (53.6 °F) during the winter at sea level. The winter rains and the melting of the snow that accumulates on the Andes produce rivers whose flow varies with the seasons, but which carry water year round. Their deep Transverse Valleys provide broad areas for cattle raising and, most important, fruit growing, an activity that has developed greatly since the mid-1970s. Nearly all Chilean pisco is produced in the near north.

As in the far north, the coastal areas of the near north have a distinct microclimate. In those sections where the airborne moisture of the sea is trapped by high bluffs overlooking the ocean, temperate rain forests develop as the vegetation precipitates the vapor in the form of a misty rain. Because the river valleys provide breaks in the coastal elevations, maritime moisture can penetrate inland and further decrease the generally arid climate in those valleys. The higher elevations in the interior sections are covered with shrubs and cacti of various kinds.

Central Chile

Central Chile (Chile Central), home to a majority of the population, includes the three largest metropolitan areas—Santiago, Valparaíso, and Concepción. It extends from about 32° south latitude to about 37° south latitude. The climate is of the temperate Mediterranean type, with the amount of rainfall increasing considerably and progressively from north to south. In the Santiago area, the average monthly temperatures are about 19.5 °C (67.1 °F) in the summer months of January and February and 7.5 °C (45.5 °F) in the winter months of June and July; the average monthly precipitation is no more than a trace in January and February and 69.7 mm (3 in) in June and July. In Concepción, by contrast, the average monthly temperatures are somewhat lower in the summer at 17.6 °C (63.7 °F) but higher in the winter at 9.3 °C (48.7 °F), and the amount of rain is much greater: in the summer, Concepción receives an average of 0.8 inch (20 millimeters) of rain per month; in June and July, the city is pounded by an average of 10 inches (253 mm.) per month. The numerous rivers greatly increase their flow as a result of the winter rains and the spring melting of the Andean snows, and they contract considerably in the summer. The combination of abundant snow in the Andes and relatively moderate winter temperatures creates excellent conditions for Alpine skiing.

The topography of central Chile includes a coastal range of mountains running parallel to the Andes. Lying between the two mountain ranges is the so-called Central Valley, which contains some of the richest agricultural land in the country, especially in its northern portion. The area just north and south of Santiago is a large producer of fruits, including the grapes from which the best Chilean wines are made. Exports of fresh fruit began to rise dramatically in the mid-1970s because Chilean growers had the advantage of being able to reach markets in the Northern Hemisphere during winter in that part of the world. Most of these exports, such as grapes, apples, and peaches, go by refrigerator ships, but some, such as berries, go by air freight.

The southern portion of central Chile contains a mixture of some excellent agricultural lands, many of which were covered originally with old-growth forests. They were cleared for agriculture but were soon exhausted of their organic matter and left to erode. Large tracts of this worn-out land, many of them on hilly terrain, have been reforested for the lumber, especially for the cellulose and paper industries. New investments during the 1980s in these industries transformed the rural economy of the region. The pre-Andean highlands and some of the taller and more massive mountains in the coastal range (principally the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta) still contain large tracts of old-growth forests of remarkable beauty, some of which have been set aside as national parks. Between the coastal mountains and the ocean, many areas of central Chile contain stretches of land that are lower than the Central Valley and are generally quite flat. The longest beaches can be found in such sections.

The South

Although many lakes can be found in the Andean and coastal regions of central Chile, the south (Sur de Chile) is definitely the country's most lacustrine area. Southern Chile stretches from below the Bío-Bío River at about 37° south latitude to Chacao channel at about 42° south latitude. In this lake district of Chile, the valley between the Andes and the coastal range is closer to sea level, and the hundreds of rivers that descend from the Andes form lakes, some quite large, as they reach the lower elevations. They drain into the ocean through other rivers, some of which (principally the Calle-Calle River, which flows by the city of Valdivia) are the only ones in the whole country that are navigable for any stretch. The Central Valley's southernmost portion is submerged in the ocean and forms the Gulf of Ancud. Isla de Chiloé, with its rolling hills, is the last important elevation of the coastal range of mountains.

The south is one of the rainiest areas in the world. One of the wettest spots in the region is Valdivia, with an annual rainfall of 2,535.4 mm (99.8 in). The summer months of January and February are the driest, with a monthly average precipitation of 67 mm (2.6 in). The winter months of June and July each produce on average a deluge of 410.6 mm (16.2 in). Temperatures in the area are moderate. In Valdivia, the two summer months average 16.7 °C (62.1 °F), whereas the winter months average 7.9 °C (46.2 °F).

The lakes in this region are remarkably beautiful. The snow-covered Andes form a constant backdrop to vistas of clear blue or even turquoise waters, as at Todos los Santos Lake. The rivers that descend from the Andes rush over volcanic rocks, forming numerous white-water sections and waterfalls. The vegetation, including many ferns in the shady areas, is a lush green. Some sections still consist of old-growth forests, and in all seasons, but especially in the spring and summer, there are plenty of wildflowers and flowering trees. The pastures in the northernmost section, around Osorno, are well suited for raising cattle; milk, cheese, and butter are important products of that area. All kinds of berries grow in the area, some of which are exported, and freshwater farming of various species of trout and salmon has developed, with cultivators taking advantage of the abundant supply of clear running water. The lumber industry is also important. A number of tourists, mainly Chileans and Argentines, visit the area during the summer.

Many of Chile's distinctive animal species have been decimated as they have been pushed farther and farther into the remaining wilderness areas by human occupation of the land. This is the case with the huemul, a large deer, and the Chilean condor, the largest bird of its kind; both animals are on the national coat of arms. The remaining Chilean cougars, which are bigger than their California cousins, have been driven to isolated national parks in the south by farmers who continue to hunt them because they occasionally kill sheep and goats.

The Far South

In the far south (Chile Austral), which extends from between 42° south latitude to Cape Horn, the Andes and the South Pacific. In the northern part of the far south, there is still plenty of rainfall. The summer months average 206.1 mm (8 in), whereas the winter months average 300 mm (12 in). The temperatures at sea level in Puerto Aisén average 13.6 °C (56.5 °F) in the summer months and 4.7 °C (40.5 °F) in the winter months. The area generally is chilly and wet, and houses a combination of channels, fjords, snow-capped mountains, and islands of all shapes and sizes within a narrow space. The southern part of the far south includes the city of Punta Arenas, which, with about 125,000 inhabitants, is the most southern city in Chile. It receives much less precipitation; its annual total is only 438.5 mm (17 in), or a little more than what Valdivia receives in the month of June alone. This precipitation is distributed more or less evenly throughout the year, with the two main summer months receiving a monthly average of thirty-one millimeters and the winter months 38.9 mm (2 in), some of it in the form of snow. Temperatures are colder than in the rest of the country. The summer months average 11.1 °C (52.0 °F), and the winter months average 2.5 °C (36.5 °F). The virtually constant wind from the South Pacific Ocean makes the air feel much colder.

The far south contains large expanses of pastures that are often used for raising sheep, even though overgrazing is an issue in some areas. The area's other main economic activity is oil and natural gas extraction from the areas around the Strait of Magellan. This strait is one of the world's important sea-lanes because it unites the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through a channel that avoids the rough open waters off Cape Horn. The channel is perilous, however, and Chilean pilots guide all vessels through it.

Area and boundaries

Area:

total:

756,102 km2 (291,933 sq mi)

land:

743,812 km2 (287,187 sq mi)

water:

12,290 km2 (4,745 sq mi)

note:

includes Easter Island (Isla de Pascua) and Isla Sala y Gómez

This does not include the Chilean claims to Antarctica, which overlaps with the Argentinian and British claims. All Antarctic claims are frozen under the Antarctic treaty.

Area - comparative:

Canada: roughly half the size of Quebec

US: slightly smaller than twice the size of Montana

Land boundaries:

total:

7,801 km (4,847 mi)

border countries:

Argentina 6,691 km (4,158 mi), Bolivia 942 km (585 mi), Peru 168 km (104 mi)

Coastline: 6,435 km (3,999 mi)

Maritime claims:

territorial sea:

12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi)

contiguous zone:

24 nmi (44.4 km; 27.6 mi)

exclusive economic zone:

200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi)

continental shelf:

200–350 nmi (370.4–648.2 km; 230.2–402.8 mi)

Extremes

Latitude and longitude

- North: tripartite border with Bolivia and Peru

- Southernmost point can be either:

- Mainland: Águila Islet, Diego Ramírez Islands

- Including Antártica: The South Pole

- Westernmost point: Motu Nui, off Easter Island

- Easternmost point can be either:

- Mainland: Nueva Island

- Including Antártica: the 53rd meridian west over Antarctica

Elevation

- highest point: Ojos del Salado 6,893 m (22,615 ft)

- lowest point: Pacific Ocean 0 m (0 ft)

Resources and land use

Natural resources: copper, timber, iron ore, nitrates, precious metals, molybdenum, hydropower, thermal power, nutrient-rich ocean currents

Land use:

arable land:

1.80%

permanent crops:

0.61%

other:

97.59% (2012)

Irrigated land: 11,990 km2 (4,629 sq mi) (2003)

Total renewable water resources: 922 km3 (2011)

Freshwater withdrawal (domestic/industrial/agricultural):

total:

26.67 km3/yr (4%/10%/86%)

per capital:

1,603 m3/yr (2007)

Environmental concerns

Natural hazards: severe earthquakes; active volcanism; tsunamis

Environment - current issues: widespread deforestation, mining; air pollution from industrial and vehicle emissions; water pollution from raw sewage.

Environment - international agreements:

party to:

Antarctic Treaty, Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Nuclear Test Ban, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution (MARPOL 73/78), Wetlands, Whaling

signed, but not ratified:

Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol

Geography - note: strategic location relative to sea lanes between Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (Strait of Magellan, Beagle Channel, Drake Passage); Atacama desert is one of world's driest regions

Antipodes

.png)

Chile is largely antipodal to China, from Arica and Tarapacá (antipodal to Hainan) to Los Lagos. Santiago (or more precisely Rancagua) is close to antipodal with the ancient Chinese city of Xi'an; Valdivia is opposite Wuhai. From Chiloé to Wellington Island, Chile is antipodal to Mongolia, including the capital Ulan Bator, while the Straits of Magellan and Tierra del Fuego correspond to southern Siberia and Lake Baikal, with Puerto Natales antipodal to Ulan Ude, the capital of the Russian republic of Buryatia. Easter Island finds its antipodes in the western corner of Rajasthan, India.

See also

- Climate of Chile

- Fjords and channels of Chile

- Geology of Chile

- List of islands of Chile

- List of lakes of Chile

- List of rivers of Chile

- List of volcanoes in Chile

Notes

- ↑ In the Spanish-speaking tropics, invierno or "winter" means "rainy season" (The University of Chicago Spanish-English/English-Spanish Dictionary, Fourth Edition (1992), by Carlos Castillo, Otto F. Bond, and D. Lincoln Canfield. Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-74348-1.)

- ↑ "Travel map of the Andes". Nelles Map. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

References

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

External links

- Chilean Navy, "General piloting regulations and information", STRAIT OF MAGELLAN, CHILEAN CHANNELS AND FIORDS Regulations and information for PILOTING. ROUTES (in Spanish), http://www.web.directemar.cl/, archived from the original on 8 October 2012, retrieved 16 April 2013 External link in

|publisher=(help) - Chilean Navy, "Sailing along the Strait of Magellan or Drake Passage", STRAIT OF MAGELLAN, CHILEAN CHANNELS AND FIORDS Regulations and information for PILOTING. ROUTES (in Spanish), http://www.web.directemar.cl/, archived from the original on 24 November 2012, retrieved 16 April 2013 External link in

|publisher=(help) - Chilean Navy, "Sailing throughout Chilean Straits, Channels and Fjords", STRAIT OF MAGELLAN, CHILEAN CHANNELS AND FIORDS Regulations and information for PILOTING. ROUTES (in Spanish), http://www.web.directemar.cl/, archived from the original on 26 November 2012, retrieved 16 April 2013 External link in

|publisher=(help) - Ministerio de Obras Públicas de Chile (2012), "Maps of all regions of Chile", Cartas camineras 2010 in 200 dpi and 70 dpi resolution available (jpg and pdf) (Maps) (in Spanish), Government of Chile, archived from the original on 4 September 2012, retrieved 20 April 2013

- United States Hydrographic Office, South America Pilot (1916)

- Geographic Chart of the Kingdom of Chile by Alonso de Ovalle