George Leo Haydock

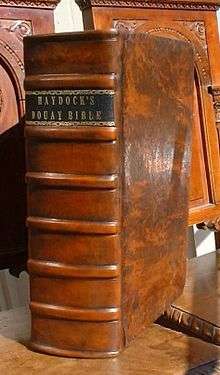

George Leo Haydock (1774–1849), scion of an ancient English Catholic Recusant family, was a priest, pastor and Bible scholar. His edition of the Douay Bible with extended commentary, originally published in 1811, became the most popular English Catholic Bible of the 19th century on both sides of the Atlantic. It remains in print and is still regarded for its apologetic value.

His eventful early years included a narrow scrape with the French Revolution and a struggle to complete his priestly studies in the years before Catholic Emancipation. He would go on to serve poor Catholic missions in rural England.

Early years

George Leo Haydock was born on 11 April 1774 in Cottam, Preston, Lancashire, the heart of Catholic resistance to the Penal Laws that the English government used to enforce Anglicanism. His parents were George Haydock and his second wife, Anne (née Cottam), who produced a generation that would become outstanding in Catholic service. Their eldest son, James Haydock (1765–1809), became a priest who died caring for the sick of his congregation during an epidemic; the next, Thomas Haydock (1772–1859), became a prominent publisher of Catholic books. Among three daughters, Margaret (1767? - 1854), joined the Augustinian nuns, taking the name Sister Stanislaus. George was the youngest son. He and his father were namesakes of an illustrious ancestor, Blessed George Haydock (1556–1584), a martyred "seminary priest" during the Elizabethan persecution, beatified in 1987. While attending a school established for Catholic students at Mowbreck Hall, Wesham, George received Confirmation, taking the name Leo, after the fifth-century saint, Pope Leo I, whose liturgical feast was at that time celebrated on Haydock's birthday (see General Roman Calendar as in 1954). In 1785, at eleven years of age, he was sent to further his education at the English College, Douai, (English spelling, Douay or Doway ) France, established in the 16th century for Catholic exiles, where provision was made for secondary education.

George Haydock's studies were interrupted in 1793, when the United Kingdom declared war on France. Authorities of the French revolutionary government closed the English College and imprisoned some of its pro-England students. George Haydock managed to avoid capture and escaped back to England in the company of his brother and fellow student, Thomas. There was an unsettled period while English Catholic bishops made hasty provision for the continuing education in England of the many refugees from Douai. After a stay at St. Edmund's College, Ware, Old Hall Green in Hertfordshire, Haydock was able in 1796 to resume his studies in earnest at a seminary established at Crook Hall, near Consett in County Durham (not to be confused with present-day Crook Hall & Gardens in Durham City). He was ordained a priest there in 1798, and remained as a professor until 1803, when the pastoral phase of his career began.

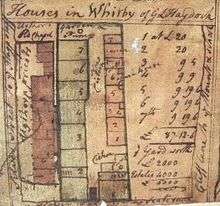

During the period of Penal Laws there was no official Catholic hierarchy in England, so there were no Catholic dioceses or parishes. A Bishop was called a Vicar Apostolic and presided over "missions" in his jurisdiction. Haydock's first assignment was at Ugthorpe, Yorkshire, a poor rural mission. It is interesting to note that despite the legal disabilities of Catholics during this time, the Haydock family had been resourceful enough to retain a measure of local influence and wealth. Although George Leo was the youngest son, he and his older sister Elizabeth appear to have been entrusted with handling the family finances. He demonstrated considerable proficiency in this regard, acquiring investment properties in the areas where he served as pastor as we will see below. He thus had independent sources of income which he often used to subsidize the missions he served.

The Mission at Ugthorpe

Hardly considered a desirable assignment, the small, poor Ugthorpe Mission was nonetheless a challenge enthusiastically met by the young priest. He promptly repaired and improved the existing execrable 1768 thatched roof structure that served as a Catholic chapel and shortly thereafter began planning for a new one. The Catholic Relief Act of 1791, although far from repealing all anti-Catholic legislation, had allowed for the building of Catholic chapels, albeit with severe architectural restrictions. Haydock eventually completed his new chapel and presbytery in 1810, and later added a school, a building that still stands (see picture at right). He also found time and opportunity to ply his property acquisition and management talents. "I have plunged into an ocean of business of farther shores of which I cannot yet descry," he wrote to his family. "I propose staying here (God willing) [the] remainder of my days." In the letter he expresses interest in acquiring land to raise cattle and farm grain, wheat, barley and potatoes. Although he was not destined to remain in Ugthorpe for the rest of his days, he would nonetheless complete his most memorable achievement while serving there.

The Haydock Bible

While at Ugthorpe, Father Haydock completed his Magnum Opus: commentary for a new edition of the English Catholic Bible. That Bible was called the Douay Version (Douay-Rheims Bible), originally translated from the Latin Vulgate in the 16th century chiefly by Gregory Martin, one of the first professors at the English College, Douai (University of Douai). It was revised and newly annotated in the 18th century by Richard Challoner (1691–1781), a scholar at University of Douai and then Vicar Apostolic of the London District, and later by Father Bernard MacMahon (1736?-1816). Haydock took his text from the Challoner-MacMahon revision, but added a substantially extended commentary. This commentary was partly original and partly compiled from Patristic writings and the writings of later Bible scholars. The Bible had long been used to advance the Protestant cause. However, Catholics used it effectively in their counteroffensive. As Haydock states in his Preface, "To obviate the misinterpretations of the many heretical works which disgrace the Scripture, and deluge this unhappy country, has been one main design of the present undertaking."

The commentary is extensive in its number of annotations and far ranging in scope. Mostly, the annotations explain words or phrases that are not clear or offer interesting elaborations of the text. However, they also deal with textual and interpretational differences with Protestants and address issues with deists and atheists. In his note to Exodus 20:4, in which the Douay Version mentions "a graven thing," Haydock states, "Protestants insidiously translate "any graven image," [original KJV] though pesel, eidolon, glupton, and sculptile, in the Heb. Gr. and Lat. denote a graven thing or idol......They know that the object of prohibition is the making and adoring of idols. But they probably wish to keep the ignorant under the stupid delusion of supposing that Catholics are idolaters, because they have images..." Pointing to the limitations of human knowledge and the resulting need for Faith, he offers in the note to Genesis 1:15, "Shall anyone pretend to wisdom, and still call into question the mysteries of faith, transubstantiation, &c., when the most learned confess they cannot comprehend the nature even of a grain of sand?" He often uses Scripture to justify specific Catholic practices. For example, in his note to Exodus 29:4, which refers to Aaron and his sons being washed with water after entering the door of the tabernacle, he states, "It is for this reason we take holy-water, when we go into our chapels, and we wash our fingers before and during Mass." In some cases he makes specific scientific observations. For example, in the note to Genesis 1:14, he states the Earth revolves around the Sun at the speed of 58,000 miles an hour (actual rate is 67,000). He also delves deeply into speculation about the Bible's mysteries. For example, in the note to Genesis 2:8 he states the following regarding the size of the Garden of Eden: " How great might be its extent we do not know. If the sources of the Ganges, Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates, be not now changed, and if these be the rivers which sprung from the fountains of Paradise, (both of which points are undecided), the garden must have comprised a great part of the world." Annotations to the New Testament are in a similar vein, but were not compiled by Haydock. Given the enormous scope of annotating the entire Bible, he was unable to maintain the demanding production schedule in addition to his pastoral duties at Ugthorpe. Therefore, another Douay alumnus, Father Benedict Rayment (1764–1842), was called on for assistance. He and a group of colleagues compiled the New Testament portion of the commentary. There was contemporary criticism that haste in preparation of the commentary resulted in some errors. However, given the spartan resources available for Catholic publishing in England at the time, the Haydock Bible must be considered a remarkable achievement.

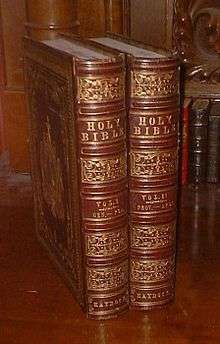

George's brother, Thomas, was the Bible's publisher. Production began in 1811 and was completed in 1814, in a large, folio edition. As were many editions of the Bible at the time, Haydock's was published and sold by subscription, a few leaves at a time. Subscribers would accumulate the sets of leaves over the years and ultimately have the completed Bible bound. Different copies have general title pages dated 1811, 1812, 1813 or 1823, showing variously Thomas Haydock's Manchester or Dublin locations. English Catholics enthusiastically welcomed this impressive volume that symbolized a reinvigorated Catholicism on the verge of winning its long fight to repeal the Penal Laws. At least 1,500 copies of the first edition were sold.

Duties of an English Catholic Priest in Recusant Times

After Ugthorpe, Father Haydock's next assignment was at the east coast port of Whitby. While there, he continued his literary career with a series of prayer books (see Other Published Works below), responding to an increasing desire by Catholic congregations to increase participation in the Mass. One book in particular, A Key to the Roman Catholic Office..., is of especial interest. This wide ranging work includes, among other things, a detailed list of the duties expected of a contemporary Catholic priest as follows:

"We have frequently to say Mass and the Divine Office, which occupies two hours every day, we are bound to attend to the work of the ministry, to catechize the ignorant, to instruct converts and strayed sheep both in public and in private, to attend for many hours in the cold confessional ( a delightful employment! some dissolute but ignorant people would suppose,) to visit the sick, even those affected with the plague or the most contagious diseases, some of whom live at the distance of 30 or 40 miles from us. We have to preach twice on all the Sabbath Days, (which term denotes all 10-I holidays,) during which, the service lasts about five hours; we have to baptize, prepare people for their first communion, with great solicitude, as well as for confirmation and the last sacrament; we have to perform what is requisite for the solemnization of marriage, and the burial of the dead, privately; we also have to church women, though we do not go to their houses for that purpose ! We keep registers of baptisms, &c. which are now allowed by the magistrate. All this we perform gratis. Still we have no tithes or surplice fees, which, in the Establishment [Anglican Church], are found so exorbitant.

"Some of us ( I speak from many years' experience) do not receive from our people £5 a year; nor above £50, including the Salary or Benefice, which has been left by our departed friends often encumbered with weighty obligations. After going through a course of education at the College for about 12 years, which costs annually between £40 and £50, we have to furnish a house and provide the necessary ornaments for the altar; wine, candles, books, &c. at our own charge, being debarred of any advantages from speculations in trade, or from Matrimony, that our thoughts may be wholly consecrated to the Lord and to the good of our people."

While at Whitby he also continued his practice of acquiring investment properties (see diagram at right).

Pastoral troubles

Also while at Whitby, Haydock continued to serve Ugthorpe as well for most of the period until 1827 when a permanent successor was assigned. At this point, a series of problems began coming to a head. The new Ugthorpe priest, Father Nicholas Rigby (1800–1886), felt Haydock personally should pay a debt owed by the Ugthorpe mission. Prior to this, Haydock had disputed the transfer of a donation originally intended for his Whitby mission to the recently established Ushaw College, Durham. Given the generosity Haydock had shown in providing financial support from his own funds to his assigned missions, he felt ill used by these actions. He made his objections known to his superiors, Thomas Smith (1763–1831), Vicar Apostolic of the Northern Vicariate, and Smith's Coadjutor Thomas Penswick (1772–1836), a former classmate of Haydock's at Douay; however, they sided with his opponents. Willingness to accept assignments to impoverished missions and compassion for his flock are among Haydock's well-documented virtues; however, patience with those trying to take financial advantage of him was not. He made his objections known without mincing words. As a result, an annoyed Smith transferred Haydock to a private chaplaincy at Westby Hall, Lancashire, in 1830. This was despite a petition by Haydock's Whitby parishioners to Smith expressing "regret to hear your Lordship's intention is to remove from us our most worthy and most beloved Pastor The Rev'd Geo Leo Haydock." Haydock's ability to support himself financially was a significant factor in these parishioners' consideration as illustrated by their request, "...that your Lordship will take into your serious consideration the depressed state of by far the greatest part of these your petitioners who are not able to contribute any thing towards the support of a Priest." But the petition was ignored, and Haydock's situation would only grow worse. Smith died in 1831 and was succeeded by the sterner disciplinarian Penswick, who immediately interdicted Haydock from saying Mass. Haydock's older sister Margaret (Sister Stanislaus, O.S.A.), understanding too well her brother's temperament, later admonished him, "...keep quiet and silent in regard of your Bishop for I see plainly you will have nothing but vexation and no redress [;] beware of scandal by publishing your sentiments of him."

While these events were unfolding, English Catholics finally won passage of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. Ironically, just after this victory so long sought after by him and his ancestors, Father Haydock was forced into retirement by his own Catholic superior. In 1831 he dutifully settled at The Tagg (sometimes spelled Tag) in Cottam, a dower house the Haydock family had retained after an ancestor had sold its larger Cottam Hall estate. Haydock remained there for eight years, "devoting himself to study, with his books all around him, lining the walls, and piled in heaps on the floors." In 1832 he made two unsuccessful appeals to Rome of his interdiction. The appeals were sent through a fellow former Douay student and pupil of Haydock's at Crook Hall, Robert Gradwell. Gradwell had served for a time in Rome and had been appointed coadjutor to the Vicar Apostolic of the London District. However, rather than sending the appeals to Rome, Gradwell sent them to Penswick, who ignored them. Another appeal after Penswick's death was successful, resulting in restoration of Haydock's priestly faculties in 1839.

The Tagg was pulled down circa 1985 and has been replaced by a modern building at the corner of Tag Lane and Tanterton Hall Lane in Cottam. Traces of evidence of its former existence remain in the area. There is a nearby street, Tag Farm Court, and another street, Cottam Hall Lane, which is a paved over former footpath to the old Haydock ancestral home, Cottam Hall. The name "Tagg House" still appears on a nearby electrical switching station.

Final assignment and death

Immediately upon his reinstatement, Haydock was given a new assignment at Penrith, Cumbria (then known as Cumberland), another poor mission with discouraging prospects. His meticulous records give an idea of the contemporary Catholic population, consisting primarily of laborers and peddlers, plus two "beggars" and one "pauper." In a letter dated 1848, he states, "I have baptized above 100[.] But many of them trampers are gone." However, he goes on to state he was able to increase his income due to shrewd investments. An incident of particular note during Haydock's pastorate occurred in 1846. Immigration from Ireland, especially resulting from the catastrophic Potato Famine beginning in 1845, meant that a large part of Haydock's congregation was Irish. Many of these found employment in the wave of railroad construction then ongoing in the Penrith area. A laborer in this position was called a navigator or navvy; and Irish navvies were often willing to accept wages less than their native-born counterparts. The obvious potential for hostility came to a head in February, 1846, when conflicts between gangs of Irish and English navvies required intervention by local authorities. At one point, Haydock is credited with dissuading an Irish gang from a planned attack against these authorities, apparently using influence earned from his pastoral work.

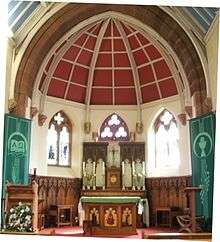

Father Haydock's letters during this period indicate a lengthy history of suffering from an apparent heart ailment, a problem that did not slow his endeavors. He continued working zealously at the mission and began construction of a new church. In September, 1849, just two months before his death, he wrote, " I do not often consult doctors nor do I require any relaxation or to retire to your smug parlor on account of my excessive labour." His new church, a red sandstone gothic structure named for St. Catherine, was completed, but Haydock did not live to see it. He died on 29 November 1849, just a few months before its completion, and is believed buried in an unmarked grave under the chancel. St. Catherine's Church still exists, its congregation now part of the Lancaster Diocese. The original memorial tablet erected in Father Haydock's memory has been lost, but was recently replaced with a copy. It includes his family motto: (Latin: "Tristitia vestra vertetur in gaudium," meaning "Your sorrow shall be turned to joy") from St John 16:20. In 2013 the church built a community centre named in Haydock's honor. A copy of his Bible is on display in the Church, to the left of the chancel near where he is buried.

Haydock's enduring legacy

2011 was the bicentennial anniversary of the Haydock Bible. Its substantial and continuing popularity is reflected in its long history of varied editions. It would remain continuously in print until at least 1910 with a long series of publishers in England and America, and would enjoy a renewal of interest at the end of the 20th century, spurring a new series of reprints and modern digital reproductions. Present day Traditional Roman Catholics who see uncertainty of purpose in the post-Conciliar Church have found inspiration in the English Catholic Recusant movement and in Father Haydock's confident expression of Faith. The following history of editions shows how the Haydock Bible with its changes over the years has made a continuing contribution to Catholic apologetics:

- 1811–1814: the first edition, folio. Despite successful sales, this expensively produced edition was a financial loss to George's brother Thomas, whose enthusiasm for publishing Catholic books far exceeded his business acumen, and to George, who personally subsidized the project. It is ironic that despite George Leo's overall proficiency in financial affairs, the achievement he would be most remembered for turned out to be a financial failure.

- 1822–1824: an octavo edition. Undismayed by the above experience, Thomas took on several partners to produce this smaller edition. It states on its title page that it is revised and diligently compared with the Latin Vulgate by the Rev. Geo. Leo Haydock. However, it lacks the extended commentary and is poorly printed with many errors, including an egregious one in II Corinthians 10:4, where the word fornications appears in place of fortifications.

- 1823: In this year a new title page appeared for the folio series, styled "Second Edition." It is not truly a new edition, as most of the folio copies were already mixtures of leaves published separately at Thomas Haydock's Manchester and Dublin presses.

- 1823–25: the first American edition, folio. The Haydock Bible's popularity quickly spread across the Atlantic. Irish immigrant Eugene Cummiskey of Philadelphia published this edition that remains to this day the only folio Catholic Bible ever published in America.

- 1831: the New Testament portion of the original folio edition issued with a new title page by Thomas Haydock. It is unclear whether he reissued the entire Bible at this time.

- 1845–48: a quarto edition begun by MacGregor, Polson & Company of Glasgow and Charles Dolman of London, and completed by A. Fullarton and Co. of Dublin, London, and Edinburgh. This series remained in print with a series of publishers into the 1870s. This was the last edition published during Father Haydock's lifetime.

- 1852–54: a quarto edition by American publisher Edward Dunigan and Brother of New York. This edition includes a revised New Testament text. This revision was begun by Father James Bayley (1814–1877), who was appointed Bishop of Newark during publication, and completed by Father James McMahon (1814–1901), who was responsible for most of the work. This edition was frequently reissued by a series of publishers into the 1880s.

- ca. 1853: a quarto edition by George Henry and Co. of London, and initially distributed in America by George Virtue of New York. In this edition the commentary was abridged by Canon F. C. Husenbeth (1796–1872). This was the probably the most successful of the Haydock editions, remaining in print through the rest of the century. Circa 1880, The National Publishing Company of Philadelphia imported the stereotype plates from England and mass marketed editions over the imprints of wide range of local booksellers and printing companies, and even got the recently established Montgomery Ward national mail order firm to include it in their catalogue. An extraordinarily large number of copies must have been printed, judging by how frequently surviving copies are met with in the second hand book trade. A copy of this edition was used in the Inauguration of President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) in 1961, coincidentally the 150th anniversary of Haydock's first edition.

- ca. 1868: a quarto edition by P. O'Shea of New York. Some copies appeared in large (Imperial) quarto. This obscure edition features an abridged version of the commentary.

- ca. 1874–1878: a large (Imperial) quarto edition by Virtue and Company Limited, of London. In this edition, two converts from the Oxford Movement, Frs. Frederick Oakeley (1802–1880) and Thomas Law (1836–1904) thoroughly revised the commentary to incorporate advances in Biblical scholarship since Haydock's time. An American edition by P. F. Collier of New York, founder of Collier's Weekly magazine, appeared ca. 1884. British editions remained in print until 1910.

- 1988: a quarto reproduction of the New Testament portion of the ca. 1853 (George Henry) edition supra by Catholic Treasures, Monrovia, California.

- 1992: a quarto reproduction of an 1859 reprint of the Edward Dunigan and Brother edition supra by Catholic Treasures, Monrovia, California. This edition has been reissued in 2000, 2006, and remains in print.

- 1999: a CD entitled Douay Bible 99 issued by Catholic Software of Murray, KY, featuring text and commentary that can be displayed on a computer in a split-screen format.

- 2007: On Line Edition; see link below.

Beginning with the ca. 1874–1878 (Virtue and Company) edition, title pages to the New Testament sections incorrectly credit Father Haydock with the New Testament commentary. Since the names of Father Rayment and his associates were never mentioned, even in the earliest editions, their contribution was forgotten over the years. This error also occurs on the later printings of the ca. 1853 (George Henry) edition.

The Haydock name became so popular and so closely associated with English Catholic Bibles in the 19th century that at least one publisher ca. 1886 "pirated" it for an edition that included only the standard Challoner annotations by adding the statement to the spine of his edition, Challoner's Notes and Other Important Features of the Haydock Bible. During the 1940s and 1950s, some "pocket" editions of the Catholic New Testament (usually referred to as the Rheims Testament when published separately) appeared, erroneously crediting "Canon Haydock" with the annotations.

Other published works

Father Haydock's other publications are brief devotional works. These were so overshadowed by his edition of the Bible and are now so rare, that they are often overlooked. However, modern historian Muchael A. Mullett has pointed out they were a significant part of a liturgical renewal taking place among the growing Catholic recusant population the verge of winning Emancipation. Haydock also wrote lengthier works paraphrasing the Psalms and Canticles of the Roman Office and began a series of Biblical Disquisitions intended as a supplement to his Bible. Regretfully, these were never published, probably due to the erratic fortunes of his brother, Thomas.

- Prayers before and after Mass, Proper for Country Congregations, 1822

- A Key to the Roman Catholic Office; Briefly Shewing the Falsehood of Fox's Martyrology, the Invocation of Saints, &c., Not Idolatrous; the Meaning of the Litanies, &c. The Kalendar: Containing a Short Account of the Chief Saints: Their Titles, Countries, & the Year of Their Happy Death: with a Variety of Prayers, etc. etc., 1823

- A Collection of Catholic Hymns, 1823

- A New Collection of Catholic Psalms, Hymns, Motettos, Anthems, and Doxologies. 1823

- The Method of Sanctifying the Sabbath Days at Whitby, Scarborough, &c., The Second Edition, with Various Additional Instructions, by the Rev. George Leo Haydock, 1824

His publications also include an 1809 table entitled The Tree of Life, depicting a summary of Church history from Adam to the current time.

Portrait and Drawings

Portrait and copies of Haydock's drawings are provided by Simon Nuttall, a descendant of the Gillow family of Catholic Recusants, who kindly gave permission for their reproduction.

See also

- Douay-Rheims Bible

- Roman Catholicism in Great Britain (The Eighteenth Century & The Catholic Revival in the Nineteenth Century)

References

- Brady, W. Maziere, The Episcopal Succession in England, Scotland and Ireland 1400–1875, 3 vols., 1876–77

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907–1913

- Cotton, Henry C. , Rhemes and Doway, 1855.

- Gillow, Joseph:

- Harris, P. R. [ed.], Douai College Documents 1639–1794, 1972

- Herbert, A.S., Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible 1525–1961, 1968

- Mullett, Michael A., The End Crowns the Work; George Leo Haydock 1774–1849, North West Catholic History Society, Wigan, 2012.

- O'Callaghan, E. B., A List of Editions of the Holy Scriptures and Parts Thereof, Printed in America Previous to 1860, Albany, 1861.

- Ohlhausen, Sidney K.:

- "America's Only Folio Catholic Bible," Bible Editions and Versions, October, 2002.

- "The Last Haydock Bible," Recusant History, October 1995

- "Folio Editions of Catholic Bibles and Testaments, A Comprehensive Bibliography," Recusant History, October 2002

- "The American Catholic Bible in the 19th Century, A Catalog of English Language Editions," 2006

- "Preface to the 2006 edition," Haydock Bible, Catholic Treasures

- "A Typographical Study of the Early Haydock Folio Bibles," Quadrat, Issue 24, Summer, 2011.

- "The Bicentennial of the Haydock Bible: 1811–2011," Bible Editions & Versions,Vol. 12, No. 4, Oct-Dec, 2011.

- "The Haydock Bible after Two Centuries," North West Catholic History, Vol. XL, 2013.

- Personal photographic archive

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- Taylor, Ronald W., "The Suspension of George Leo Haydock from his Priestly Duties (1831-1838), North West Catholic History, 2014

- Ushaw College, Durham, The Haydock Archives

- Walsh, Rev. Thomas, & Taylor, Ron, "The Haydock Registers: A Picture of Young Catholics in Penrith 1841–1851", North West Catholic History, 2005

- Ward, Bernard, The Dawn of the Catholic Revival in England 1781–1803, 2 vols., 1909

External links

- Complete Online Haydock Bible Commentary with Douay-Rheims Bible and Latin Vulgate Bible

- Haydock Bible Title Page Reproductions

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- First American Haydock Bible

- Haydock's Church in Penrith

- History of the Douay Bible

- Cottam Parish History

- Libraries with copies of Haydock's works

- President Kennedy's Inaugural with Haydock Bible

- Vice President Biden's Inaugural with Haydock Bible

- Remains of the building where the English College at Douay was temporarily located in Rheims