Gertie the Dinosaur

| Gertie the Dinosaur | |

|---|---|

Gertie driven to tears by her master | |

| Directed by | Winsor McCay |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 12 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

Gertie the Dinosaur is a 1914 animated short film by American cartoonist and animator Winsor McCay. It is the earliest animated film to feature a dinosaur. McCay first used the film before live audiences as an interactive part of his vaudeville act; the frisky, childlike Gertie did tricks at the command of her master. McCay's employer William Randolph Hearst later curtailed McCay's vaudeville activities, so McCay added a live-action introductory sequence to the film for its theatrical release. McCay abandoned a sequel, Gertie on Tour (c. 1921), after producing about a minute of footage.

Although Gertie is popularly thought to be the earliest animated film, McCay had earlier made Little Nemo (1911) and How a Mosquito Operates (1912). The American J. Stuart Blackton and the French Émile Cohl had experimented with animation even earlier; Gertie being a character with an appealing personality distinguished McCay's film from these earlier "trick films". Gertie was the first film to use animation techniques such as keyframes, registration marks, tracing paper, the Mutoscope action viewer, and animation loops. It influenced the next generation of animators such as the Fleischer brothers, Otto Messmer, Paul Terry, and Walt Disney. John Randolph Bray unsuccessfully tried to patent many of McCay's animation techniques and is said to have been behind a plagiarized version of Gertie that appeared a year or two after the original. Gertie is the best preserved of McCay's films—some of which have been lost or survive only in fragments—and has been preserved in the US National Film Registry.

Background

Winsor McCay (c. 1867–71 – 1934)[lower-alpha 1] had worked prolifically as a commercial artist and cartoonist by the time he started making newspaper comic strips such as Dream of the Rarebit Fiend (1904–11)[lower-alpha 2] and his signature strip Little Nemo (1905–14).[lower-alpha 3][6] In 1906, McCay began performing on the vaudeville circuit, doing chalk talks—performances in which he drew before live audiences.[7]

Inspired by the flip books his son brought home,[8] McCay "came to see the possibility of making moving pictures"[9] of his cartoons. He claimed that he "was the first man in the world to make animated cartoons",[9] though he was preceded by the American James Stuart Blackton and the French Émile Cohl.[9] McCay's first film starred his Little Nemo characters and debuted in movie theatres in 1911; he soon incorporated it into his vaudeville act.[10] He followed it in 1912 with How a Mosquito Operates,[11] in which a giant, naturalistically animated mosquito sucks the blood of a sleeping man.[12] McCay gave the mosquito a personality and balanced humor with the horror of the nightmare situation.[13] His animation was criticized as being so lifelike that he must have traced the characters from photographs[14] or resorted to tricks using wires;[15] to show that he had not, McCay chose a creature that could not have been photographed for his next film.[14]

McCay conferred with the American Historical Society in 1912, and announced plans[16] for "the presentation of pictures showing the great monsters that used to inhabit the earth".[17] He spoke of the "serious and educational work" that the animation process could enable.[18] McCay had earlier introduced dinosaurs into his comic strip work, such as a March 4, 1905,[lower-alpha 4][19] episode of Dream of the Rarebit Fiend in which a Brontosaurus skeleton took part in a horse race,[20] and a May 25, 1913,[lower-alpha 5] Rarebit Fiend episode in which a hunter unsuccessfully targets a dinosaur; the layout of the background to the latter bore a strong resemblance to what later appeared in Gertie.[22] In the September 21, 1913,[lower-alpha 6] episode of McCay's Little Nemo strip In the Land of Wonderful Dreams, titled "In the Land of the Antediluvians", Nemo meets a blue dinosaur named Bessie which has the same design as that of Gertie.[lower-alpha 7][18]

McCay considered a number of names before settling on "Gertie"; his production notebooks used "Jessie the Dinosaurus". Disney animator Paul Satterfield recalled hearing McCay in 1915 relate how he had chosen the name "Gertie":[18]

He heard a couple of "sweet boys" [gay men] out in the hall talking to each other, and one of them said, "Oh, Bertie, wait a minute!" in a very sweet voice. He thought it was a good name, but wanted it to be a girl's name instead of a boy's, so he called it "Gertie".— Paul Satterfield, Interview with Milt Gray, 1977[18]

Content

Gertie_the_Dinosaur.webm.jpg)

Gertie the Dinosaur is the earliest animated film to feature a dinosaur.[25] Its star Gertie does tricks much like a trained elephant. She is animated in a naturalistic style unprecedented for the time; she breathes rhythmically, she shifts her weight as she moves, and her abdominal muscles undulate as she draws water. McCay imbued her with a personality—while friendly, she could be capricious, ignoring or rebelling against her master's commands.[26]

Synopsis

When her master McCay calls her, the frisky, childlike Gertie appears from a cave. Her whip-wielding master has her do tricks such as raising her foot or bowing on command. When she feels she has been pushed too far, she nips back at her master. She cries when he scolds her, and he placates her with a pumpkin.[lower-alpha 9] Throughout the act, prehistoric denizens such as a flying lizard continually distract Gertie. She tosses a mammoth in the lake; when it teases her by spraying her with water, she hurls a boulder at it as it swims away. After she quenches her thirst by draining the lake, McCay has her carry him offstage while he bows to the audience.[28]

Production

_Gertie_the_Dinosaur_-_Gerite_carries_MccCay_in_her_mouth.jpg)

Gertie was McCay's first piece of animation with detailed backgrounds.[18] Main production began in mid-1913.[29] Working in his spare time,[30] McCay drew thousands of frames of Gertie on 6 1⁄2-by-8 1⁄2-inch (17 cm × 22 cm) sheets of rice paper,[29] a medium good for drawing as it did not absorb ink, and as it was translucent it was ideal for the laborious retracing of backgrounds,[31] a job that fell to art student neighbor John A. Fitzsimmons.[29] The drawings themselves occupied a 6-by-8-inch (15 cm × 20 cm) area of the paper,[lower-alpha 10] marked with registration marks in the corners[31] to reduce jittering of the images when filmed. They were photographed mounted on large pieces of stiff cardboard.[29]

McCay was concerned with accurate timing and motion; he timed his own breathing to determine the timing of Gertie's breathing, and included subtle details such as the ground sagging beneath Gertie's great weight.[29] McCay consulted with New York museum staff to ensure the accuracy of Gertie's movements; the staff were unable to help him find out how an extinct animal would stand up from a lying position, so in a scene in which Gertie stood up, McCay had a flying lizard come on screen to draw away viewers' attention.[32] When the drawings were finished, they were photographed at Vitagraph Studios in early 1914.[33]

McCay pioneered the "McCay Split System" of animation, in which major poses or positions were drawn first and the intervening frames drawn after. This relieved tedium and improved the timing of the film's actions.[32] McCay was open about the techniques that he developed, and refused to patent his system, reportedly saying, "Any idiot that wants to make a couple of thousand drawings for a hundred feet of film is welcome to join the club."[34] During production of Gertie, he showed the details to a visitor who claimed to be writing an article about animation. The visitor was animator John Randolph Bray,[35] who sued McCay in 1914[36] after taking advantage of McCay's lapse to patent many of the techniques, including the use of registration marks, tracing paper, and the Mutoscope action viewer, and the cycling of drawings to create repetitive action.[37] The suit was unsuccessful, and there is evidence that McCay may have countersued—he received royalty payments from Bray for licensing the techniques.[38]

Release

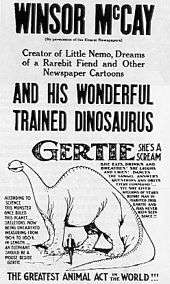

Gertie the Dinosaur first appeared as part of McCay's vaudeville act in early 1914.[33] It appeared in movie theaters[39] in an edition with a live-action prologue, distributed by William Fox's Box Office Attractions Company from December 28.[40] Dinosaurs were still new to the public imagination at the time of Gertie's release[41]—a Brontosaurus skeleton was put on public display for the first time in 1905.[42] Advertisements reflected this by trying to educate audiences: "According to science this monster once ruled this planet ... Skeletons [are] now being unearthed measuring from 90 ft. to 160 ft. in length. An elephant should be a mouse beside Gertie."[41]

Vaudeville

McCay originally used a version of the film as part of his vaudeville act.[lower-alpha 11] The first performance was on February 8, 1914,[lower-alpha 12][33] in Chicago at the Palace Theater. McCay began the show making his customary live sketches, which he followed with How a Mosquito Operates. He then appeared on stage with a whip and lectured the audience on the making of animation. Standing to the right of the film screen, he introduced "the only dinosaur in captivity". As the film started Gertie poked her head out of a cave, and McCay encouraged her to come forward. He reinforced the illusion with tricks such as tossing a cardboard apple at the screen, at which point he turned his back to the audience and pocketed the apple as it appeared in the film for Gertie to eat.[lower-alpha 13] For the finale, McCay walked offstage from where he "reappeared" in the film; Gertie lifted up the animated McCay, placed him on her back, and walked away as McCay bowed to the audience.[28]

The show soon moved to New York.[44] Though reviews were positive, McCay's employer at the New York American, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, was displeased that his star cartoonist's vaudeville schedule interrupted his work illustrating editorials. At Hearst's orders, reviews of McCay's shows disappeared from the American's pages. Shortly after, Hearst refused to run paid advertisements from the Victoria Theater, where McCay performed in New York.[45] On March 8, Hearst announced a ban on artists in his employ from performing in vaudeville.[46] McCay's contract did not prohibit him from his vaudeville performances, but Hearst was able to pressure McCay and his agents to cancel bookings, and eventually McCay signed a new contract barring him from performing outside of greater New York.[39]

Movie theaters

In November 1914, film producer William Fox offered to market Gertie the Dinosaur to moving-picture theaters for "spot cash and highest prices".[47] McCay accepted, and extended the film to include a live-action prologue[lower-alpha 14] and intertitles to replace his stage patter. The film successfully traveled the country and had reached the west coast by December.[39]

The live-action sequence was likely shot on November 19, 1914.[49] It features McCay with several of his friends,[39] such as cartoonists George McManus and Tad Dorgan, writer Roy McCardell, and actor Tom Powers;[50] McCay's son Robert had a cameo as a camera-room assistant.[39] McCay used a bet as a plot device, as he had previously in the Little Nemo film.[51]

As the film opens, McCay and friends suffer a flat tire in front of the American Museum of Natural History. They enter the museum, and while viewing a Brontosaurus skeleton, McCay wagers a dinner that he can bring a dinosaur to life with his animation skills. The animation process and its "10,000 drawings, each a little different from the one preceding it" is put on display,[lower-alpha 15][26] with humorous scenes of mountains of paper, some of which an assistant drops.[53] When the film is finished, the friends gather to view it in a restaurant.[26]

McCay and animation after Gertie

McCay's working method was laborious, and animators developed a number of methods to reduce the workload and speed production to meet the demand for animated films. Within a few years of Nemo's release, Canadian Raoul Barré's registration pegs combined with American Earl Hurd's cel technology became near-universal methods in animation studios.[54] McCay used cel technology[55] in his follow-up to Gertie, The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918).[56] It was his most ambitious film at 25,000 drawings,[55] and took nearly two years to complete, but was not a commercial success.[57]

.jpg)

McCay made six more films, though three of them were never made commercially available.[58] After 1921, McCay was made to give up animation when Hearst learned he devoted more of his time to animation than to his newspaper illustrations.[59] Unexecuted ideas McCay had for animation projects included a collaboration with Jungle Imps author George Randolph Chester, a musical film called The Barnyard Band,[60] and a film about the Americans' role in World War I.[61]

In 1927, McCay attended a dinner in his honor in New York. After a considerable amount of drinking, McCay was introduced by animator Max Fleischer. McCay gave the gathered group of animators some technical advice, but when he felt the audience was not giving him attention, he berated them, saying, "Animation is an art. That is how I conceived it. But as I see, what you fellows have done with it, is making it into a trade. Not an art, but a trade. Bad Luck!"[62] That September he appeared on the radio at WNAC, and on November 2 Frank Craven interviewed him for The Evening Journal's Woman's Hour. During both appearances he complained about the state of contemporary animation.[63] McCay died July 26, 1934,[64] of a cerebral embolism.[65]

Reception and legacy

Gertie pleased audiences and reviewers.[66] It won the praise of drama critic Ashton Stevens in Chicago, where the act opened.[67] On February 22, 1914, before Hearst had barred the New York American from mentioning McCay's vaudeville work, a columnist in the paper called the act "a laugh from start to finish ... far funnier than his noted mosquito drawings".[44] On February 28 the New York Evening Journal called it "the greatest act in the history of motion picture cartoonists".[45] Émile Cohl praised McCay's "admirably drawn" films, and Gertie in particular, after seeing them in New York before he returned to Europe.[68] Upon its theatrical release, Variety magazine wrote the film had "plenty of comedy throughout" and that it would "always be remarked upon as exceptionally clever".[69]

A fake version of Gertie the Dinosaur appeared a year or two after the original; it features a dinosaur performing most of Gertie's tricks, but with less skillful animation, using cels on a static background.[70] It is not known for certain who produced the film, though its style is believed to be that of Bray Productions.[71] Filmmaker Buster Keaton rode the back of a clay-animated dinosaur in homage to Gertie in Three Ages (1923).[51]

McCay's first three films were the earliest animated works to have a commercial impact; their success motivated film studios to join in the infant animation industry.[72] Other studios used McCay's combination of live action with animation, such as the Fleischer Studios series Out of the Inkwell (1918–1929)[15] and Walt Disney's Alice Comedies series (1923–1927).[73] McCay's clean-line, high-contrast, realistic style set the pattern for American animation to come, and set it apart from the abstract, open forms of animation in Europe.[74] This legacy is most apparent in the feature films of the Walt Disney Animation Studios, for example in Fantasia (1940), which included anthropomorphic dinosaurs animated in a naturalistic style, with careful attention to timing and weight. Shamus Culhane, Dave and Max Fleischer, Walter Lantz, Otto Messmer, Pat Sullivan, Paul Terry, and Bill Tytla were among the generation of American animators who drew inspiration from the films they saw in McCay's vaudeville act.[75] Gertie's reputation was such that animation histories long named it as the first animated film.[53]

_Gertie_on_Tour.webm.jpg)

Around 1921, McCay worked on a second animated film featuring Gertie, titled Gertie on Tour. The film was to have Gertie bouncing on the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, attempting to eat the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., wading in on the Atlantic City shore, and other scenes.[76] The film exists only in concept sketches and in one minute of film footage in which Gertie plays with a trolley and dances before other dinosaurs.[77]

Since his death, McCay's original artwork has been poorly preserved;[30] much was destroyed in a late-1930s house fire, and more was sold off when the McCays needed money.[78] About 400 original drawings from the film have been preserved, discovered by animator Robert Brotherton in disarray in the fabric shop of Irving Mendelsohn, into whose care McCay's films and artwork had been entrusted in the 1940s.[79] Besides some cels from The Sinking of the Lusitania, these Gertie drawings are the only original animation artwork of McCay's to have survived.[80] McCay destroyed many of his original cans of film to create more storage space. Of what he kept, much has not survived, as it was photographed on 35mm nitrate film, which deteriorates and is highly flammable in storage. A pair of young animators discovered the film in 1947 and preserved what they could. In many cases only fragments could be saved, if anything at all. Of all of McCay's films, Gertie is the best preserved.[81] Mendelsohn and Brotherton tried fruitlessly to find an institution to store McCay's films until the Canadian film conservatory the Cinémathèque québécoise approached them in 1967 on the occasion of that year's World Animation Film Exposition in Montreal. The Cinémathèque québécoise has since curated McCay's films.[lower-alpha 16][82] Of the surviving drawings, fifteen have been determined not to appear in extant copies of the film. They appear to come from a single sequence, likely at the close of the film, and have Gertie showing her head from the audience's right and giving a bow.[31]

McCay's son Robert unsuccessfully attempted to revive Gertie with a comic strip called Dino.[83] He and Disney animator Richard Huemer recreated the original vaudeville performance for the Disneyland television program in 1955;[68] this was the first exposure the film had for that generation. Walt Disney expressed to the younger McCay his feeling of debt, and gestured to the Disney studios saying, "Bob, all this should be your father's."[82] An ice cream shop in the shape of Gertie sits by Echo Lake in Disney's Hollywood Studios in Walt Disney World.[84]

New York Times film critic Richard Eder, on seeing a retrospective of McCay's animation at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1975, wrote of Gertie that "Disney ... struggled mightily to recapture" the qualities in McCay's animation, but that "Disney's magic, though sometimes scary, was always contained; McCay's approached necromancy". Eder compared McCay's artistic vision to that of poet William Blake's, saying "it was too strange and personal to be generalized or to have any children".[85]

Gertie has been written about in hundreds of books and articles.[83] Animation historian Donald Crafton called Gertie "the enduring masterpiece of pre-Disney animation".[33] Brothers Simon and Kim Deitch loosely based their graphic novel The Boulevard of Broken Dreams (2002) on McCay's disillusionment with the animation industry in the 1920s. The story features an aged cartoonist named Winsor Newton,[lower-alpha 17] who in his younger years had a Gertie-like stage act featuring a mastodon named Milton.[87] Gertie has been selected for preservation in the US National Film Registry.[88]

See also

- Animation in the United States during the silent era

- Film preservation

- List of films in the public domain in the United States

- The Enchanted Drawing

Notes

- ↑ Different accounts have given McCay's birth year as 1867, 1869, and 1871. His birth records are not extant.[1]

- ↑ Rarebit Fiend was revived between 1911 and 1913 under other titles, such as Midsummer Day Dreams and It Was Only a Dream.[2]

- ↑ The strip was titled Little Nemo in Slumberland from 1905[3] to 1911, and In the Land of Wonderful Dreams from 1911[4] to 1914.[5]

- ↑

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for this comic strip.

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for this comic strip. - ↑ Though the strip appeared in the Evening Telegram on May 25, 1913, it was drawn sometime between 1908 and 1911.[21]

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for this comic strip.

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for this comic strip. - ↑

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for this comic strip.

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for this comic strip. - ↑ McCay used dinosaurs in other strips as well, such as the August 21, 1910(

Commons file page),[23] and April 22, 1912,(

Commons file page),[23] and April 22, 1912,( Commons file page)[24] episodes of Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, and a 1906 Little Sammy Sneeze episode in which Sammy destroys a dinosaur skeleton with his sneeze.[19]

Commons file page)[24] episodes of Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, and a 1906 Little Sammy Sneeze episode in which Sammy destroys a dinosaur skeleton with his sneeze.[19] - ↑

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for the complete strip.

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for the complete strip. - ↑ In the original vaudeville version, McCay used an apple rather than a pumpkin.[27]

- ↑ This was in the 1:1.33 aspect ratio that was standard for film at the time.[31]

- ↑ There are no known extent copies of the vaudeville version of Gertie.[43]

- ↑ McCay registered the copyright for Gertie the Dinosaur on September 15, 1914.[39]

- ↑ In the theatrical version, the intertitles call the apple a pumpkin.[27]

- ↑ It is not known when the live-action sequences were filmed.[48]

- ↑ David Nathan and Donald Crafton find the number 10,000 suspect, as that number of frames at 16 frames per second would result in 11 minutes of animation; extent copies of the theatrical version of the film, of which only one brief scene is known to be missing, have only seven minutes of animation. Taking cycling into account, even 11 minutes is a conservative estimate.[52]

- ↑ On the indifference of American institutions to the task, John Canemaker quotes children's book illustrator Maurice Sendak: "America 'still doesn't take its great fantasists all that seriously.'"[82]

- ↑ "Winsor Newton" is wordplay on "Winsor McCay" and "Winsor & Newton", a brand of art supplies.[86]

References

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Merkl 2007, p. 478.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 97.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 164.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 229.

- ↑ Eagan 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003; Canemaker 2005, p. 157.

- 1 2 3 Canemaker 2005, p. 157.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 160.

- ↑ Eagan 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ Barrier 2003, p. 17; Dowd & Hignite 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 167.

- 1 2 Mosley 1985, p. 62.

- 1 2 Murray & Heumann 2011, p. 92.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, p. 123.

- ↑ Motograph staff 1912, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Canemaker 2005, p. 168.

- 1 2 Merkl 2007, p. 32.

- ↑ Glut 1999, p. 199; Crafton 1993, p. 123.

- ↑ Merkl 2007, p. 488.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 168, 172–173; Merkl 2007, pp. 366–367.

- ↑ Merkl 2007, pp. 341–342.

- ↑ Merkl 2007, p. 439.

- ↑ Mitchell 1998, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Crafton 1993, p. 113.

- 1 2 Baker 2012, p. 7.

- 1 2 Canemaker 2005, pp. 175–177.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Canemaker 2005, p. 169.

- 1 2 Heer 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Nathan & Crafton 2013, p. 29.

- 1 2 Canemaker 2005, p. 171.

- 1 2 3 4 Crafton 1993, p. 110.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 171, 261.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Sito 2006, p. 36; Canemaker 2005, p. 172.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 172.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Canemaker 2005, p. 182.

- ↑ Nathan & Crafton 2013, p. 32–34.

- 1 2 Tanner 2000.

- ↑ Nathan & Crafton 2013, pp. 43.

- ↑ Nathan & Crafton 2013, p. 32.

- 1 2 Canemaker 2005, p. 177.

- 1 2 Canemaker 2005, p. 181.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 181, 261.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 182; Crafton 1993, p. 112.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, p. 112.

- ↑ Nathan & Crafton 2013, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Cullen 2004, p. 738; Crafton 1993, p. 112.

- 1 2 Crafton 1993, p. 134.

- ↑ Nathan & Crafton 2013, p. 40.

- 1 2 Thomas & Penz 2003, p. 25.

- ↑ Barrier 2003, pp. 10–14.

- 1 2 Canemaker 2005, p. 188.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 186.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 193.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Sito 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 198.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 198, 217.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 199.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 239.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 249.

- ↑ Syracuse Herald staff 1934, p. 12.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 177, 181.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, p. 110; Canemaker 2005, p. 177.

- 1 2 Crafton 1993, p. 111.

- ↑ Variety staff 1914, p. 26.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 175.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 175; Glut 2002, p. 102.

- ↑ Callahan 1988, p. 223.

- ↑ Murray & Heumann 2011, p. 93.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 257.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 192, 197.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 194.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 253–255, 258.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 258.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 254.

- 1 2 3 Canemaker 2005, p. 255.

- 1 2 Hoffman & Bailey 1990, p. 125.

- ↑ Goldsbury 2003, p. 180.

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, pp. 256, 263.

- ↑ Leopold 2003.

- ↑ Young 1991, p. 49; Hatfield 2004.

- ↑ Andrews 1991, p. 31.

Works cited

Books

- Baker, Kage (2012). Ancient Rockets. Tachyon Publications. ISBN 978-1-61696-113-8.

- Barrier, Michael (2003). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516729-0.

- Beckerman, Howard (2003). Animation: The Whole Story. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58115-301-9.

- Canemaker, John (2005). Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (Revised ed.). Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-5941-5.

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898–1928. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226116679.

- Cullen, Frank (2004). Vaudeville, old and new. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2.

- Dowd, Douglas Bevan; Hignite, Todd (2006). Strips, Toons, And Bluesies: Essays in Comics And Culture. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-621-0.

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide To The Landmark Movies In The National Film Registry. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-2977-3.

- Glut, Donald F. (1999). Carbon Dates: A Day by Day Almanac of Paleo Anniversaries and Dino Events. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-0592-3.

- Glut, Donald F. (2002). The Frankenstein Archive: Essays on the Monster, the Myth, the Movies, and More. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-8069-2.

- Goldsbury, Cara (2003). The Luxury Guide to Walt Disney World: How to Get the Most Out of the Best Disney Has to Offer. Bowman Books. ISBN 978-0-9726972-2-4.

- Hoffman, Frank W.; Bailey, William G. (1990). Arts and Entertainment Fads. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-86656-881-4.

- Merkl, Ulrich (2007). The Complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend (1904–1913) by Winsor McCay 'Silas' (.doc). Catalog of episodes & text of the book: Ulrich Merkl. ISBN 978-3-00-020751-8. (on included DVD)

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (1998). The Last Dinosaur Book: The Life and Times of a Cultural Icon. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-53204-2.

- Mosley, Leonard (1985). Disney's World: A Biography. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8128-3073-6.

- Murray, Robin L.; Heumann, Joseph K. (2011). That's All Folks?: Ecocritical Readings of American Animated Features. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3512-0.

- Sito, Tom (2006). Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2407-0.

- Thomas, Maureen; Penz, François (2003). Architectures of Illusion: From Motion Pictures to Navigable Interactive Environments. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-84150-045-4.

Journals and magazines

- Callahan, David (September–October 1988). "Cel Animation: Mass Production and Marginalization in the Animated Film Industry". Film History. Indiana University Press. 2 (3): 223–228. JSTOR 3815119.

- Hatfield, Charles (2004). "The Presence of the Artist: Kim Deitch's Boulevard of Broken Dreams vis-a-vis the Animated Cartoon". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. Department of English, University of Florida. 1 (1). Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- Heer, Jeet (2006). "Little Nemo in Comicsland". Virginia Quarterly Review. University of Virginia. 82 (2): 104–121. ISSN 2154-6932.

- Motograph staff (1912-04-04). "Making Motion Pictures by Pencil". Motograph. Electricity Magazine Corp. 7 (4): 162. LCCN xca12001192.

- Nathan, David L; Crafton, Donald (2013). "The Making and Re-making of Winsor McCay's Gertie (1914)". Animation (8): 23–46. doi:10.1177/1746847712467569. ISSN 1746-8485.

- Tanner, Ron (Summer 2000). "Terrible Lizard! the Dinosaur as Plaything". Journal of American & Comparative Cultures. Blackwell Publishing. 23 (2). doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2000.2302_53.x. ISSN 1542-734X.

- "Gertie". Variety: 26. 1914-12-19.

- Young, Frank (October 1991). "Well Done: Raw". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books: 48–51. ISSN 0194-7869.

Newspapers

- Andrews, Robert M. (1991-09-26). "Library of Congress adds 25 more films to classics collection". TimesDaily. p. 31.

- Syracuse Herald staff (1934-07-27). "Winsor M'Cay Early Comic Artist, Dies". Syracuse Herald. p. 12.

Web

- Leopold, Todd (2003-01-09). "The Strange History of a Cartoon Cat: Graphic Novel 'Boulevard of Broken Dreams' Ode to Animation". CNN.com. CNN. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gertie the Dinosaur. |

- Gertie the Dinosaur at the Internet Movie Database

- Gertie the Dinosaur at AllMovie

- Gertie the Dinosaur at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on August 24, 2016.

- "Have You Seen Gertie at Disney’s Hollywood Studios?" about Dinosaur Gertie's Ice Cream of Extinction

- Example of Dino strip by Bob McCay (attributed to Winsor McCay at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)