Grand tack hypothesis

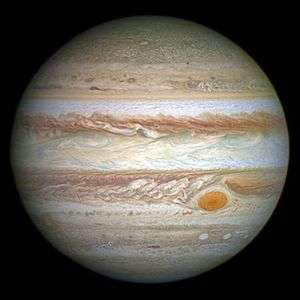

In planetary astronomy, the grand tack hypothesis proposes that after its formation at 3.5 AU, Jupiter migrated inward to 1.5 AU, before reversing course due to capturing Saturn in an orbital resonance, eventually halting near its current orbit at 5.2 AU. The reversal of Jupiter's migration is likened to the path of a sailboat changing directions (tacking) as it travels against the wind.[1]

The planetesimal disk is truncated at 1.0 AU by Jupiter's migration, limiting the material available to form Mars.[2] Jupiter twice crosses the asteroid belt, scattering asteroids outward then inward. The resulting asteroid belt has a small mass, a wide range of inclinations and eccentricities, and a population originating from both inside and outside Jupiter's original orbit.[3] Debris produced by collisions among planetesimals swept ahead of Jupiter may have driven an early generation of planets into the sun.[4]

Description

In the grand tack model Jupiter undergoes a two-phase migration after its formation, migrating inward to 1.5 AU before reversing course and migrating outward. Jupiter's formation takes place near the ice line, at roughly 3.5 AU. After clearing a gap in the gas disk Jupiter undergoes type II migration, moving slowly toward the Sun with the gas disk. If uninterrupted, this migration would have left Jupiter in a close orbit around the sun like recently discovered hot-Jupiters in other planetary systems.[5] Saturn also migrates toward the Sun, but being smaller, undergoes either type I migration or runaway migration.[6] Saturn converges on Jupiter and is captured in a 2:3 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter during this migration. An overlapping gap in the gas disk then forms around Jupiter and Saturn,[7] altering the balance of forces on these planets which are now migrating together. If the gap was completely cleared, the larger mass of Jupiter would cause their positions to shift outward relative to the gap until the torques from the inner and outer disks were balanced and the Type II migration of two planets toward the Sun would continue.[8] The interaction between the planets, however, prevents Saturn from completely clearing its part of the disk.[9] This gas is able to stream across the gap from the outer disk to the inner disk and exchanges angular momentum with the planets during its passage.[10] This process allows the planets to migrate relative to the disk and is assumed to reverse their migration when Jupiter is at 1.5 AU.[6] Their outward migration continues until the gas disk dissipates and it is supposed to end with Jupiter near its current orbit.

Scope of the grand tack hypothesis

The hypothesis can be applied to multiple phenomena in the Solar System.

Mars problem

Jupiter's grand tack resolves the Mars problem by limiting the material available to form Mars. The Mars problem is a conflict between some simulations of the formation of the terrestrial planets, which when begun with planetesimals distributed throughout the inner Solar System, end with a 0.5–1.0 Earth-mass planet in its region,[11] much larger than the actual mass of Mars, 0.107 Earth-mass. Jupiter's inward migration alters this distribution of material,[12] driving planetesimals inward to form a narrow dense band with a mix of materials inside 1.0 AU,[13] and leaving the Mars region largely empty.[14] Planetary embryos quickly form in the narrow band. While most later collide and merge to form the larger terrestrial planets, some are scattered outside the band.[6] These scattered embryos, deprived of additional material slowing their growth, form the lower mass terrestrial planets Mars and Mercury.[15]

Asteroid belt

Jupiter and Saturn drive most asteroids from their initial orbits during their migrations, leaving behind an excited remnant derived from both inside and outside Jupiter's original location. Before Jupiter's migrations the surrounding regions contained asteroids which varied in composition with their distance from the Sun.[16] Rocky asteroids dominated the inner region, while more primitive and icy asteroids dominated the outer region beyond the ice line.[17] As Jupiter and Saturn migrate inward, ~15% of the inner asteroids are scattered outward onto orbits beyond Saturn.[2] After reversing course, Jupiter and Saturn first encounter these objects, scattering about 0.5% of the original population back inward onto stable orbits.[6] Later Jupiter and Saturn migrate into the outer region, scattering 0.5% of the primitive asteroids onto orbits in the outer asteroid belt.[6] The encounters with Jupiter and Saturn leave many of the captured asteroids with large eccentricities and inclinations.[14] In some cases icy asteroids are left with orbits crossing the region where the terrestrial planets form, and by colliding with them, deliver water to them.[18][19]

Later developments

Later studies have shown that the convergent orbital migration of Jupiter and Saturn in the fading solar nebula is unlikely to establish a 3:2 mean-motion resonance. Rather, the nebula conditions lead to capture in a 2:1 mean-motion resonance.[20] This outcome is a result of the relatively slow migration velocity with which the two planets approach each other. Capture of Jupiter and Saturn in the 2:1 mean-motion resonance does not typically reverse the direction of migration, but particular nebula configurations have been identified that may drive outward migration.[21] These configurations, however, tend to excite Jupiter's and Saturn's orbital eccentricity to values between two and three times as large as their actual values.[21]

The grand tack scenario ignores the ongoing accretion of gas on Jupiter and Saturn.[22] In fact, to drive outward migration and move the planets to the proximity of their current orbits, the solar nebula had to contain a sufficiently large reservoir of gas around the orbits of the two planets. However, this gas would provide a source for accretion, which would affect the growth of Jupiter and Saturn and their mass ratio.[20] The type of nebula density required for capture in the 3:2 mean-motion resonance is especially dangerous for the survival of the two planets, because it can lead to significant mass growth and ensuing planet-planet scattering. But conditions leading to 2:1 mean-motion resonant systems may also put the planets at danger.[23]

Recent modeling of the formation of planets from a narrow annulus indicates that the quick formation of Mars, the size of the Moon-forming impact, and the mass accreted by Earth following the formation of the Moon are best reproduced if the oligarchic growth phase ended with most of the mass in Mars-sized embryos and a small fraction in planetesimals. The Moon-forming impact occurs between 60 and 130 million years in this scenario.[24]

The absence of close orbiting super-Earths in the Solar System may the the result of Jupiter's inward migration.[25] As Jupiter migrates inward, planetesimals are captured in its mean-motion resonances, causing their orbits to shrink and their eccentricities to grow. A collisional cascade follows as their relative velocities became large enough to produce catastrophic impacts. The resulting debris then spirals inward toward the Sun due to drag from the gas disk. If there were super-Earths in the early Solar System, they would have caught much of this debris in resonances and could have been driven into the Sun ahead of it. The current terrestrial planets would then form from planetesimals left behind when Jupiter reversed course.[26] However, the migration of close orbiting super-Earths into the Sun could be avoided if the debris coalesced into larger objects, reducing gas drag; and if the protoplanetary disk had an inner cavity, their inward migration could be halted near its edge.[27]

The presence of a thick atmosphere around Titan and its absence around Ganymede and Callisto may be due to the timing of their formation relative to the grand tack. If Ganymede and Callisto formed before the grand tack their atmospheres would have been lost as Jupiter moved closer to the Sun. However, for Titan to avoid Type I migration into Saturn, and for Titan's atmosphere to survive, the moon must have formed after the grand tack.[28][29]

Simulations of the formation of the terrestrial planets using models of the protoplanetary disk that include viscous heating and the migration of the planetary embryos indicate that Jupiter's migration may have reversed at 2.0 AU. The eccentricities of the embryos were excited by perturbations from Jupiter. As these eccentricities were damped by the denser gas disk of recent models, the semi-major axes of the embryos shrank, shifting the peak density of solids inward. For simulations with Jupiter's migration reversing at 1.5 AU, this resulted in the largest terrestrial planet forming near Venus's orbit rather than at Earth's orbit. Simulations that instead reversed Jupiters's migration at 2.0 AU yielded a closer match to the current Solar System.[9]

Following the grand tack, perturbations from the terrestrial planets and the Nice model instability alter the orbital distribution of the remaining asteroids. The resulting eccentricity and semi-major axis distributions resemble that of the current asteroid belt. Some low-inclination asteroids are removed, leaving the inclination distribution slightly over-excited compared to the current asteroid belt.[30]

Advocates

At the 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference held in 2014, Seth A. Jacobson, Alessandro Morbidelli, D. C. Rubie, Kevin Walsh, David P. O'Brien, Sean Raymond, S. Steart and S. Lock published a paper titled "Planet Formation within the Grand Tack Model", stating conclusions from a great number of N-body simulations of the formation of terrestrial planets.[31]

Alternatives

A small Mars forms in a small but non-zero fraction of simulations of terrestrial planet accretion that begin with planetesimals distributed across the entire inner Solar System.[32][33][34] If the accretion of the terrestrial planets occurred with Jupiter and Saturn in their present orbits (i.e. after the instability in the Nice model) a local depletion of the planetesimal disk near Mars's current orbit is sufficient for the formation of a low-mass Mars.[35] A planetesimal disk with a steep surface density profile, due to the inward drift of solids before the formation of planetesimals, also results in a small Mars and a low mass asteroid belt.[36] If the gas disk is flared and the pebbles are large, pebble accretion by planetesimals and embryos becomes significantly less efficient with increasing distance from the Sun, preventing the growth of objects beyond the size of Mars at its distance and leaving the asteroid belt with a small mass.[37][38]

The eccentricities and inclinations of a low mass asteroid belt could have been exited by secular resonances if the resonant orbits of Jupiter and Saturn became chaotic during the period between the gas phase era and the instability of the Nice model.[39][40] Explanations for the combined excitation and depletion of the asteroid belt include sweeping of secular resonances during the depletion of the gas disk and the scattering by embedded embryos. However, these explanations require a slower depletion of the gas disk than is observed and the loss of the embryos on a 100 Myr timescale.[36]

The absence of inner super-Earths and the small mass of Mercury may be due to the formation of Jupiter's core close to the Sun and its outward migration across the inner Solar System. During its outward migration this core could push material outward in its resonances leaving the region inside Venus's orbit depleted.[41][27] In a protoplanetary disk that is evolving via a disk wind planetary embryos may migrate outward in a leaving the Solar System without planets inside Mercury.[42] An instability that led to catastrophic collisions between an early generational of inner planets may have resulted in the debris being ground small enough to be lost due to Poynting-Robertson drag.[43] If planetesimal formation was limited to early in the gas disk epoch an inner edge of the planetesimal disk might be located at the silicate condensation line of this time.[44] The magnetic field of some stars may have been aligned with the rotation of the disk, causing the gas in the inner regions of their disks to be depleted faster. This would enable the solid to gas ratio to reach values high enough for the formation of planetesimals via streaming instabilities closer than Mercury's orbit in these systems.[45][46]

See also

- Formation and evolution of the Solar System

- Jumping-Jupiter scenario

- Nice model

- Planetary migration

- Late Heavy Bombardment

References

- ↑ Zubritsky, Elizabeth. "Jupiter's Youthful Travels Redefined Solar System". NASA. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- 1 2 Beatty, Kelly. "Our "New, Improved" Solar System". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Sanders, Ray. "How Did Jupiter Shape Our Solar System?". Universe Today. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. "Jupiter's 'Smashing' Migration May Explain Our Oddball Solar System". Space.com. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Fesenmaier, Kimm. "New Research Suggests Solar System May Have Once Harbored Super-Earths". Caltech. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walsh, Kevin J.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Raymond, Sean N.; O'Brien, David P.; Mandell, Avi M. (2011). "A low mass for Mars from Jupiter's early gas-driven migration". Nature. 475 (7355): 206–209. arXiv:1201.5177

. Bibcode:2011Natur.475..206W. doi:10.1038/nature10201.

. Bibcode:2011Natur.475..206W. doi:10.1038/nature10201. - ↑ "New Research Suggests Solar System May Have Once Harbored Super-Earths". Astrobiology. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Morbidelli, Alessandro; Crida, Aurélien (2007). "The dynamics of Jupiter and Saturn in the gaseous protoplanetary disk". Icarus. 191 (1): 158–171. arXiv:0704.1210

. Bibcode:2007Icar..191..158M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.04.001.

. Bibcode:2007Icar..191..158M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.04.001. - 1 2 Brasser, R.; Matsumura, S.; Ida, S.; Mojzsis, S. J.; Werner, S. C. (2016). "Analysis of terrestrial planet formation by the Grand Tack model: System architecture and tack location". The Astrophysical Journal. 821 (2): 75. arXiv:1603.01009

. Bibcode:2016ApJ...821...75B. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/821/2/75.

. Bibcode:2016ApJ...821...75B. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/821/2/75. - ↑ Masset, F.; Snellgrove, M. (2001). "Reversing type II migration: Resonance trapping of a lighter giant protoplanet". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 320 (4): L55–L59. arXiv:astro-ph/0003421

. Bibcode:2001MNRAS.320L..55M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04159.x.

. Bibcode:2001MNRAS.320L..55M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04159.x. - ↑ Raymond, Sean N.; O'Brien, David P.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Kaib, Nathan A. (2009). "Building the terrestrial planets: Constrained accretion in the inner Solar System". Icarus. 203 (2): 644–662. arXiv:0905.3750

. Bibcode:2009Icar..203..644R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.05.016.

. Bibcode:2009Icar..203..644R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.05.016. - ↑ Tim Lichtenberg, Tim. "Ripping Apart Asteroids to Account for Earth's Strangeness". Astrobites. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Carter, Philip J.; Leinhardt, Zoë M.; Elliott, Tim; Walter, Michael J.; Stewart, Sarah T. (2015). "Compositional Evolution during Rocky Protoplanet Accretion". The Astrophysical Journal. 813 (1): 72. arXiv:1509.07504

. Bibcode:2015ApJ...813...72C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/813/1/72.

. Bibcode:2015ApJ...813...72C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/813/1/72. - 1 2 Walsh, Kevin. "The Grand Tack". Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Hansen, Brad M. S. (2009). "Formation of the Terrestrial Planets from a Narrow Annulus". The Astrophysical Journal. 703 (1): 1131–1140. arXiv:0908.0743

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...703.1131H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/703/1/1131.

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...703.1131H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/703/1/1131. - ↑ Davidsson, Dr. Björn J. R. "Mysteries of the asteroid belt". The History of the Solar System. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ Raymond, Sean. "The Grand Tack". PlanetPlanet. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ O'Brien, David P.; Walsh, Kevin J.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Raymond, Sean N.; Mandell, Avi M. (2014). "Water delivery and giant impacts in the 'Grand Tack' scenario". Icarus. 239: 74–84. arXiv:1407.3290

. Bibcode:2014Icar..239...74O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.05.009.

. Bibcode:2014Icar..239...74O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.05.009. - ↑ Matsumura, Soko; Brasser, Ramon; Ida, Shigeru (2016). "Effects of Dynamical Evolution of Giant Planets on the Delivery of Atmophile Elements during Terrestrial Planet Formation". The Astrophysical Journal. 818 (1): 15. arXiv:1512.08182

. Bibcode:2016ApJ...818...15M. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/818/1/15.

. Bibcode:2016ApJ...818...15M. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/818/1/15. - 1 2 D'Angelo, G.; Marzari, F. (2012). "Outward Migration of Jupiter and Saturn in Evolved Gaseous Disks". The Astrophysical Journal. 757 (1): 50 (23 pp.). arXiv:1207.2737

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...757...50D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/757/1/50.

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...757...50D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/757/1/50. - 1 2 Pierens, Arnaud; Raymond, Sean N.; Nesvorny, David; Morbidelli, Alessandro. "Outward Migration of Jupiter and Saturn in 3:2 or 2:1 Resonance in Radiative Disks: Implications for the Grand Tack and Nice models". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 795 (1): L11. arXiv:1410.0543

. Bibcode:2014ApJ...795L..11P. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/795/1/L11.

. Bibcode:2014ApJ...795L..11P. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/795/1/L11. - ↑ D'Angelo, G.; Marzari, F. (2015). "Sustained Accretion on Gas Giants Surrounded by Low-Turbulence Circumplanetary Disks". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #47. id.418.06. Bibcode:2015DPS....4741806D.

- ↑ Marzari, F.; D'Angelo, G. (2013). "Mass Growth and Evolution of Giant Planets on Resonant Orbits". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #45. id.113.04. Bibcode:2013DPS....4511304M.

- ↑ Jacobson, S. A.; Morbidelli, A., A. (2014). "Lunar and terrestrial planet formation in the Grand Tack scenario". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 372: 174. arXiv:1406.2697

. Bibcode:2014RSPTA.37230174J. doi:10.1098/rsta.2013.0174.

. Bibcode:2014RSPTA.37230174J. doi:10.1098/rsta.2013.0174. - ↑ Batygin, Konstantin; Laughlin, Greg (2015). "Jupiter's decisive role in the inner Solar System's early evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (14): 4214–4217. arXiv:1503.06945

. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423252112.

. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423252112. - ↑ University of California Santa Cruz Press Release. "Wandering Jupiter swept away super-Earths, creating our unusual Solar System". Astronomy Now. Pole Star Publications Ltd. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- 1 2 Raymond, Sean N.; Izidoro, Andre; Bitsch, Bertram; Jacobsen, Seth A. (2016). "Did Jupiter's core form in the innermost parts of the Sun's protoplanetary disc?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 458, Issue 3, p.2962-2972. 458 (3). arXiv:1602.06573

. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw431.

. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw431. - ↑ Heller, R.; Marleau, G.-D; Pudritz, R. E. (2015). "The formation of the Galilean moons and Titan in the Grand Tack scenario". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 579: L4. arXiv:1506.01024

. Bibcode:2015A&A...579L...4H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526348.

. Bibcode:2015A&A...579L...4H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526348. - ↑ Wilson, David. "Hold on to Your Moons! Ice, Atmospheres and the Grand Tack". astrobites. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Deienno, Rogerio; Gomes, Rodney S.; Walsh, Kevin J.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Nesvorný, David (2016). "Is the Grand Tack model compatible with the orbital distribution of main belt asteroids?". Icarus. 272: 114–124. Bibcode:2016Icar..272..114D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.02.043.

- ↑

- ↑ Chambers, J. E. (2013). "Late-stage planetary accretion including hit-and-run collisions and fragmentation". Icarus. 224 (1): 43–56. Bibcode:2013Icar..224...43C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.02.015.

- ↑ Fischer, R. A.; Ciesla, F. J. (2014). "Dynamics of the terrestrial planets from a large number of N-body simulations". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 392: 28–38. Bibcode:2014E&PSL.392...28F. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.02.011.

- ↑ Barclay, Thomas; Quintana, Elisa V. (2015). "In-situ Formation of Mars-like Planets – Results from Hundreds of N-body Simulations That Include Collisional Fragmentaion". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #47. #507.06.

- ↑ Izidoro, A.; Haghighipour, N.; Winter, O. C.; Tsuchida, M. (2014). "Terrestrial Planet Formation in a Protoplanetary Disk with a Local Mass Depletion: A Successful Scenario for the Formation of Mars". The Astrophysical Journal. 782 (1): 31, (20 pp.). arXiv:1312.3959

. Bibcode:2014ApJ...782...31I. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/782/1/31.

. Bibcode:2014ApJ...782...31I. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/782/1/31. - 1 2 Izidoro, André; Raymond, Sean N.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Winter, Othon C. (2015). "Terrestrial planet formation constrained by Mars and the structure of the asteroid belt". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 453 (4): 3619–3634. arXiv:1508.01365

. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1835.

. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1835. - ↑ "Scientists predict that rocky planets formed from "pebbles"". Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ Levison, Harold F.; Kretke, Katherine A.; Walsh, Kevin; Bottke, William (2015). "Growing the terrestrial planets from the gradual accumulation of sub-meter sized objects" (PDF). PNAS. 112 (46): 14180–14185. arXiv:1510.02095

. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214180L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513364112.

. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214180L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513364112. - ↑ Izidoro, Andre; Raymond, Sean N.; Pierens, Arnaud; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Winter, Othon C.; Nesvorny, David (2016). "The Asteroid Belt as a Relic From a Chaotic Early Solar System". arXiv:1609.04970

.

. - ↑ Lichtenberg, Tim. "Modest chaos in the early solar system". astrobites. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Raymond, Sean. "Did the Solar System form inside-out?". PlanetPlanet. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ Ogihara, Masahiro; Kobayashi, Hiroshi; Inutsuka, Shu-ichiro; Suzuki, Takeru K. (2015). "Formation of terrestrial planets in disks evolving via disk winds and implications for the origin of the solar system's terrestrial planets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 579: A65. arXiv:1505.01086

. Bibcode:2015A&A...579A..65O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525636.

. Bibcode:2015A&A...579A..65O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525636. - ↑ Volk, Kathryn; Gladman, Brett (2015). "Consolidating and Crushing Exoplanets: Did It Happen Here?". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 806 (2): L26. arXiv:1502.06558

. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/806/2/L26.

. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/806/2/L26. - ↑ Morbidelli, A.; Bitsch, B.; Crida, A.; Gounelle, M.; Guillot, T.; Jacobsen, S.; Johansen, A.; Lambrechts, M.; Lega, E. (2016). "Fossilized condensation lines in the Solar System protoplanetary disk". Icarus. 267: 368–376. arXiv:1511.06556

. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.11.027.

. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.11.027. - ↑ Hammer, Michael. "Why is Mercury so far from the Sun?". astrobites. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Simon, Jacob (2016). "The Influence of Magnetic Field Geometry on the Formation of Close-in Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 827 (2): L37. arXiv:1608.00573

. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/827/2/L37.

. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/827/2/L37.