Greenbrier River

| Greenbrier River | |

| River | |

Greenbrier River at Marlinton, West Virginia | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | West Virginia |

| Counties | Greenbrier, Monroe, Pocahontas, Summers |

| Tributaries | |

| - right | Anthony Creek (Greenbrier River), Knapp Creek |

| Source | West Fork Greenbrier River [1] |

| - location | Pocahontas County |

| - elevation | 3,396 ft (1,035 m) |

| - coordinates | 38°44′07″N 79°45′37″W / 38.73528°N 79.76028°W |

| Secondary source | East Fork Greenbrier River [2] |

| - location | Pocahontas County |

| - elevation | 3,746 ft (1,142 m) |

| - coordinates | 38°41′04″N 79°39′31″W / 38.68444°N 79.65861°W |

| Source confluence | |

| - location | Durbin |

| - elevation | 2,710 ft (826 m) |

| - coordinates | 38°32′37″N 79°49′56″W / 38.54361°N 79.83222°W |

| Mouth | New River [3] |

| - location | Hinton |

| - elevation | 1,365 ft (416 m) |

| - coordinates | 37°39′13″N 80°53′05″W / 37.65361°N 80.88472°WCoordinates: 37°39′13″N 80°53′05″W / 37.65361°N 80.88472°W |

| Length | 162 mi (261 km) [4] |

| Basin | 1,656 sq mi (4,289 km2) [4] |

| Discharge | for Alderson |

| - average | 2,600 cu ft/s (74 m3/s) [5] |

| - max | 10,200 cu ft/s (289 m3/s) (2000) |

| - min | 576 cu ft/s (16 m3/s) (1976) |

| |

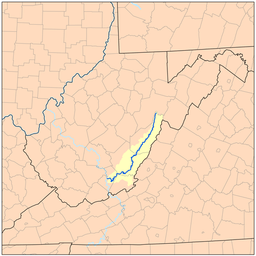

The Greenbrier River is a tributary of the New River, 173 miles (278 km) long,[4] in southeastern West Virginia, in the United States. Via the New, Kanawha and Ohio rivers, it is part of the watershed of the Mississippi River, draining an area of 1,656 square miles (4,290 km2).[4] It is one of the longest rivers in West Virginia.[6]

Course

The Greenbrier is formed at Durbin in northern Pocahontas County by the confluence of the East Fork Greenbrier River[2] and the West Fork Greenbrier River,[1] both of which are short streams rising at elevations exceeding 3,300 feet (1,000 m) and flowing for their entire lengths in northern Pocahontas County.[4][7] From Durbin the Greenbrier flows generally south-southwest through Pocahontas, Greenbrier and Summers Counties, past several communities including Cass, Marlinton, Hillsboro, Ronceverte, Fort Spring, Alderson, and Hinton, where it flows into the New River.[7]

History

Along most of its course, the Greenbrier accommodated the celebrated Indian warpath known as the Seneca Trail (Great Indian Warpath). From the vicinity of present-day White Sulphur Springs the Trail followed Anthony's Creek down to the Greenbrier near the present Pocahontas-Greenbrier County line. It then ascended the River to the vicinity of Hillsboro and Droop Mountain and made its way through present Pocahontas County by way of future Marlinton, Indian Draft Run, and Edray.

The first permanent white settlers west of the Alleghenies have traditionally been considered to have been two New Englanders: Jacob Marlin and Stephen Sewell, who arrived in the Greenbrier Valley in 1749. They built a cabin together at what would become Marlinton, but after disputing over religion, Sewell moved into a nearby hollowed-out sycamore tree. In 1751, surveyor John Lewis (father of Andrew Lewis) discovered the pair. Sewell eventually settled on the eastern side of Sewell Mountain, near present-day Rainelle. They may well have been the first to settle what was then called the "western waters" — i.e., in the regions where streams flowed westward to the Gulf of Mexico rather than eastward to the Atlantic.[8]

Colonel John Stuart (1749–1823), a Revolutionary War commander and pioneering western Virginia settler, surveyed and settled the Greenbrier Valley and is known locally as the "Father of Greenbrier County". At the age of twenty, Stuart was a member of the 1769 survey by citizens of Augusta County, Virginia, which explored the wilderness of the Greenbrier Valley to the west in preparation for European settlement. The following year he built the first mill in present-day Greenbrier County, at Frankford. In 1774, he led a company of Greenbrier troops in the Battle of Point Pleasant at the confluence of the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers. He was among Lewisburg's first trustees and in 1780 he became Greenbrier County's first clerk, leaving many historic records behind.

Uses

The Greenbrier is the longest untamed (unblocked) river left in the Eastern United States.[9] It is heavily used for recreational pursuits.[4] Its upper reaches flow through the Monongahela National Forest,[7] and it is paralleled for 77 miles (124 km) by the Greenbrier River Trail, a rail trail which runs between the communities of Cass and North Caldwell.[10]

It has always been a valuable water route, with the majority of the important cities in the watershed being established riverports. The river gives the receiving waters of the New River an estimated 30% of its water volume. Over three-fourths of the watershed is an extensive karstic (cavern system), which supports fine trout fishing, cave exploration and recreation. Many important festivals and public events are held along the river throughout the watershed.

In honor of the river's use in the state's logging history, the West Virginia State Park, Cass Scenic Railroad in Cass has a car called "The Greenbrier River."[11]

Variant names

According to the Geographic Names Information System, the Greenbrier River has also been known historically as:[3]

- Green Briar River

- Green Brier River

- Green Bryar River

- Greenbriar River

- O-ne-pa-ke (Lenape for Dark Path)

- O-ne-pa-ke-cepe (Lenape for Dark Path Water or River)

- Onepake

- Riviere de la Ronceverte (River of the Greenbrier)

- We-o-to-we

- We-o-to-we-cepe-we

- Weotowe

Geology

Caves and karst

The unique karstlands of the Greenbrier River Valley — underlain by the Greenbrier Limestone Formation — constitute one of the world's densest sinkhole plains, with an average of 18 sinkholes per square kilometer. This green "moonscape" of collapsed craters is a unique problem for development as the ground is prone to subsidization. It is impossible to tell how large a cave system is by looking at the surface, and developers often build their structures too close to the open spaces beneath the ground. There is no current karst protection plan for any of the counties that are involved with this problem.

The aggregated caves and karst of the Greenbrier River Valley are among the world's Top Ten Endangered Karst Ecosystems as listed by the Karst Waters Institute in 2001.[12]

West Virginia State Fossil

American vertebrate paleontology arguably began in the sub-watershed of Second Creek, a Greenbrier tributary. Bones discovered by saltpeter miners in Haynes Cave close to the river in Monroe County were sent to (future President) Thomas Jefferson, who identified them as a previously unknown species. Without a skull for identification purposes, Jefferson used the eight-inch claws as an identifying mark, and named the skeleton, Megalonyx or "Great Claw". Later the bones were positively identified as that of a giant ground sloth. The name "jeffersonii" was later added to it in tribute. For years the sloth was mistakenly thought to be from another cave within the watershed, Organ Cave, but recent research indicates that Haynes Cave was the cave of origin. The Megalonyx jeffersonii is now the state fossil of West Virginia.

West Virginia State Gemstone

The West Virginia state gemstone is also part of the Greenbrier River watershed: The Lithostrotionella, a fossilized form of coral[13] that is found in the Hillsdale Limestone group in Pocahontas and Greenbrier counties. Not an official gemstone, it is a siliceous chalcedony. It is found almost exclusively within Greenbrier and Pocahontas counties.[14]

Ecology

The Greenbrier hosts one of the state's two endemic species of salamanders, the West Virginia Spring Salamander in Fort Spring. The other salamander, the Cheat Mountain Salamander lives in the mountains of the headwaters.

The Candy Darter of Knapp Creek (Finescale saddled darter) is a survivor to when the Greenbrier followed a more ancient drainage pattern with Teays Valley.

Threats to the Greenbrier

The river is vulnerable to Nonpoint source pollution and sediment from timbering and flooding. It has been on the WV List of Impaired Streams since 2006 for the contamination of fecal coliform bacteria. Algae is becoming a known nuisance upon the waters, primarily in warm weather, and there is a need to study how much water can be pulled out of the river to supply the needs of communities in a state that practices little in the way of water conservation, even in times of drought. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection and various concerned citizen groups are working to prevent further stresses upon the river.

On December 17, 2009 the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection's James Summers released a report on its findings of algae in West Virginia rivers. The Greenbrier was deemed the most algae-affected river in the state, due to nutrient source tracking. Steps are currently being made to address this issue.[15]

Maps

The New River Atlas has successfully mapped the Greenbrier from Ronceverte to Hinton, West Virginia.[16] The Atlas shows the original batteau channels and historic man-made impacts.

See also

- Battle of Greenbrier River

- List of West Virginia rivers

- Cass Scenic Railroad State Park

- Watoga State Park

- Greenbrier River Trail State Park

References

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: West Fork Greenbrier River

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: East Fork Greenbrier River

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Greenbrier River

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McNeel, William P. "Greenbrier River." The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Ken Sullivan, editor. Charleston, WV: West Virginia Humanities Council. 2006. ISBN 0-9778498-0-5.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey; USGS 03183500 GREENBRIER RIVER AT ALDERSON, WV; retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ greenbrierriver.org

- 1 2 3 DeLorme (1997). West Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer. Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme. ISBN 0-89933-246-3.

- ↑ e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia "Marlin and Sewell." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 08 October 2010. Web. 04 August 2015.

- ↑ http://www.8riverssafedevelopment.com/sys/getFile.php?file=documents/vg_aug_sep_2006_p20.pdf

- ↑ Greenbrier River Trail website

- ↑ http://www.cassrailroad.com/whittaker.html

- ↑ Tronvig, Kristen A. and Belson, Christopher S. "Top Ten List of Endangered Karst Ecosystems" The Karst Waters Institute 2000/2001, retrieved on 25 April 2009.

- ↑ Species:Lithostrotionella

- ↑ http://www.e-referencedesk.com/resources/state-gemstone/west-virginia.html

- ↑ Summers, James (2009-12-17). "Assessment of Filamentous Algae in the Greenbrier River and other West Virginia Streams" (PDF). West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection.

- ↑ Trout, William E. III. The New River Atlas: Historic sites on the New River. Virginia Canals and Navigations Society.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greenbrier River. |

- Map of the Greenbrier River watershed

- The Greenbrier River Watershed Association

- Friends of the Lower Greenbrier River

- The Greenbrier River Trail and The Great Greenbrier River Race

- Allegheny Mountain Radio

- Durbin Days, Durbin and Greenbrier Valley Railroad

- Battle of Lewisburg

- Ronceverte River Festival

- Riders of the Flood

- The Festival of the Rivers in Hinton