Grévy's zebra

| Grévy's zebra[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Grévy's zebra at Buffalo Springs National Reserve. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | E. grevyi |

| Binomial name | |

| Equus grevyi Oustalet, 1882 | |

| |

| Grévy's zebra range (blue — native, red — introduced) | |

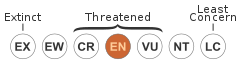

The Grévy's zebra (Equus grevyi), also known as the imperial zebra, is the largest extant wild equid and the largest and most threatened of the three species of zebra, the other two being the plains zebra and the mountain zebra. Named after Jules Grévy, it is the sole extant member of the subgenus Dolichohippus. The Grévy's zebra is found in Kenya and Ethiopia. Compared with other zebras, it is tall, has large ears, and its stripes are narrower.

The Grévy's zebra lives in semi-arid grasslands where it feeds on grasses, legumes, and browse; it can survive up to five days without water. It differs from the other zebra species in that it does not live in harems and has few long-lasting social bonds. Male territoriality and mother–foal relationships form the basis of the social system of the Grévy's zebra. This zebra is considered to be endangered. Its population has declined from 15,000 to 3,000 since the 1970s. However, as of 2008, the population is stable.

Taxonomy and naming

The Grévy's zebra was first described by French naturalist Émile Oustalet in 1882. He named it after Jules Grévy, then president of France, who, in the 1880s, was given one by the government of Abyssinia. Traditionally, this species was classified in the subgenus Dolichohippus with plains zebra and mountain zebra in Hippotigris. Fossils of zebra-like equids have been found throughout Africa and Asia in the Pliocene and Pleistocene deposits.[3] Notable examples include E. sanmeniensis from China, E. cautleyi from India, E. valeriani from central Asia and E. oldowayensis from East Africa.[3] The latter, in particular is very similar to the Grévy's zebra and may have been its ancestor.[3] The modern Grévy's zebra arose in the early Pleistocene.[3] Zebras appear to be a monophyletic linage[4][5][6] and recent (2013) phylogenies have placed Grevy's zebra in a sister taxon with the plains zebra.[4] In areas where Grévy's zebras are sympatric with plains zebras, the two may gather in same herds[7] and fertile hybrids do occur.[8]

Description

The Grévy's zebra is the largest of all wild equines. It is 2.5–2.75 m (8.2–9.0 ft) from head to tail with a 55–75 cm (22–30 in) tail, and stands 1.45–1.6 m (4.8–5.2 ft) high at the shoulder. These zebras weigh 350–450 kg (770–990 lb).[9][10] Grévy's zebra differs from the other two zebras in its more primitive characteristics.[11]:147 It is particularly mule-like in appearance; the head is large, long, and narrow with elongated nostril openings;[11]:147 the ears are very large, rounded, and conical and the neck is short but thick.[12] The zebra's muzzle is ash-grey to black in colour with the lips having whiskers. The mane is tall and erect; juveniles have a mane that extends to the length of the back and shortens as they reach adulthood.[12]

As with all zebra species, the Grevy's zebra's pelage has a black and white striping pattern. The stripes are narrow and close-set, being broader on the neck, and they extend to the hooves.[12] The belly and the area around the base of the tail lack stripes which is unique to the Grevy's zebra. Foals are born with brown and white striping, with the brown stripes darkening as they grow older.[12] Embryological evidence has shown that the zebra's background colour is dark and the white is an addition.[3] The stripes of the zebra may serve to make it look bigger than it actually is or disrupt its outline. It appears that a stationary zebra can be inconspicuous at night or in shade.[12] Experiments have suggested that the stripes polarize light in such a way that it discourages biting horse-flies in a manner not shown with other coat patterns.[13] Other studies suggest that, when moving, the stripes may confuse observers, such as mammalian predators and biting insects, via two visual illusions, the wagon wheel effect, where the perceived motion is inverted, and the barber pole illusion, where the perceived motion is in a wrong direction.[14]

Range and ecology

The Grévy’s zebra largely inhabits northern Kenya, with some isolated populations in Ethiopia.[11]:147[12] It was extirpated from Somalia and Djibouti and its status in South Sudan is uncertain.[2] It lives in Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and barren plains.[7] Ecologically, this species is intermediate between the arid-living African wild ass and the water-dependent plains zebra.[7][11]:147 Lactating females and non-territorial males use areas with green, short grass and medium, dense bush more often than non-lactating females and territorial males.[15]

Grévy's zebras rely on grasses, legumes, and browse for nutrition.[12] They commonly browse when grasses are not plentiful.[7][16] Their hindgut fermentation digestive system allows them to subsist on diets of lower nutritional quality than that necessary for ruminant herbivores. Grevy's zebras can survive up to five days without water, but will drink daily when it is plentiful.[17] They often migrate to better watered highlands during the dry season.[7] Females require significantly more water when they are lactating.[18] During droughts, the zebras will dig water holes and defend them.[7] Grévy's zebras are preyed on by lions, hyenas, wild dogs, cheetahs and leopards.[12] In addition, they are susceptible to various gastro-intestinal parasites, notably of the Trichostrongylus genus.[19]

Behaviour and life history

Adult males mostly live in territories during the wet seasons but some may stay in them year round if there's enough water left.[7] Stallions that are unable to establish territories are free-ranging[11]:151 and are known as bachelors. Females, young and non-territorial males wander through large home ranges. The females will wander from territory to territory preferring the ones with the highest-quality food and water sources.[20] Up to nine males may compete for a female outside of a territory.[12] Territorial stallions will tolerate other stallions who wander in their territory, however when an oestrous female is present the territorial stallion keeps other males at bay.[7][11]:151 Non-territorial males may avoid territorial ones because of harassment.[15] When females are not around, a territorial stallion will seek the company of other stallions. The stallion shows his dominance with an arched neck and a high-stepping gait and the least dominant stallions submit by extending their tail, lowering their heads and nuzzling their superior's chest or groin.[11]:151

Zebras produce numerous sounds and vocalisations, when alarmed, they produce deep hoarse grunts. Whistling and squealing are made when alarmed, during fights, or when scared or in pain. Snorting may be produced when scared or as a warning. A male will bray in defense of its territory, when driving females, or keeping other males at bay. Barking may be made during copulation and distressed foals will squeal.[12] The call of the Grévy's zebra has been described as "something like a hippo's grunt combined with a donkey's wheeze".[7] To get rid of flies or parasites, they roll in dust, water or mud or, in the case of flies, twitch their skin. They also rub against trees, rocks and other objects to get rid of irritations like itchy skin, hair or parasites.[12] Although Grévy's zebras do not perform mutual grooming, they do sometimes rub against a conspecific.[12]

Reproduction

Grévy's zebras can mate and give birth year-round, but most mating takes place in the early rainy seasons and births mostly take place in August or September after the long rains.[12] An oestrous mare may visit though as many as four territories a day[20] and will mate with the stallions in them. Among territorial stallions, the most dominant ones control territories near water sources, which mostly attract mares with dependant foals,[21] while more subordinate stallions control territories away from water with greater amounts of vegetation, which mostly attract mares without dependant foals.[21]

The resident stallions of territories will try to subdue the entering mares with dominance rituals and then continue with courtship and copulation.[7] Grévy's zebra stallions have large testicles and can ejaculate a large amount of semen to replace the sperm of other males.[20] This is a useful adaptation for a species whose females mate polyandrously. Bachelors or outside territorial stallions sometimes "sneak" copulation of mares in another stallion’s territory.[20] While female associations with individual males are brief and mating is promiscuous, females who have just given birth will reside with one male for long periods and mate exclusively with that male.[20] Lactating females are harassed by males more often than non-lactating ones and thus associating with one male and his territory provides an advantage as he will guard against other males.[22]

Gestation of the Grévy's zebra normally lasts 390 days,[12] with a single foal being born. A newborn zebra will follow anything that moves, so new mothers prevent other mares from approaching their foals while imprinting their own striping pattern, scent and vocalisation on them.[12] Females with young foals may gather into small groups.[18] Mares may leave their foals in "kindergartens" while searching for water.[18] The foals will not hide, so they can be vulnerable to predators.[7] However, kindergartens tend to be protected by an adult, usually a territorial male.[18] A female with a foal stays with one dominant territorial male who has exclusive mating rights to her. While the foal will not likely be his, the stallion will look after it to ensure that the female stays in his territory.[23] To adapt to a semi-arid environment, Grévy's zebra foals have longer nursing intervals and wait until they are three months old before they start drinking water.[18] Although offspring became less dependant on their mothers after half a year, associations with them continue for up to three years.[7]

Relationship with humans

.jpg)

The Grévy's zebra was known to the Europeans in antiquity and was used by the Romans in circuses.[3] It was subsequently forgotten in the Western world for a thousand years.[3] In the seventeenth century, the king of Shoa (now central Ethiopia) exported two zebras; one to the Sultan of Turkey and another to the Dutch governor of Jakarta.[3] A century later, in 1882, the government of Abyssinia sent one to French president Jules Grévy. It was at that time that the animal was recognised as its own species and named in Grévy’s honour.[3]

Status and conservation

The Grévy's zebra is considered endangered.[2] Its population was estimated to be 15,000 in the 1970s and by the early 21st century the population was lower than 3,500, a 75% decline.[24]:11 It is estimated that there are less than 2,500 Grévy's zebras still living in the wild.[2] There are also an estimated 600 Grévy's zebras in captivity.[24]:20 Captive herds have been known to thrive, like at White Oak Conservation in Yulee, Florida, United States, where more than 70 foals have been born. There, research is underway in partnership with the Conservation Centers for Species Survival on semen collection and freezing and on artificial insemination.[25] The Grévy's zebra population trend is considered stable as of 2008.[2]

The Grévy's zebra is legally protected in Ethiopia. In Kenya, it is protected by the hunting ban of 1977. In the past, Grévy's zebras were threatened mainly by hunting for their skins which fetched a high price on the world market. However, hunting has declined and the main threat to the zebra is habitat loss and competition with livestock. Cattle gather around watering holes and the Grévy's zebras are fenced from those areas.[24]:17 Community-based conservation efforts have shown to the most effective in preserving Grévy's zebras and their habitat. Less than 0.5% of the range of the Grévy's zebra is in protected areas. In Ethiopia, the protected areas include Alledeghi Wildlife Reserve, Yabelo Wildlife Sanctuary, Borana Controlled Hunting Area and Chalbi Sanctuary. In Kenya, important protected areas include the Buffalo Springs, Samburu and Shaba National Reserves and the private and community land wildlife conservancies in Isiolo, Samburu and the Laikipia Plateau.[2]

The Mesquite plant was introduced into Ethiopia around 1997 and is endangering the zebra's food supply. The Mesquite plant is an invasive species replacing the two grass species, Cenchrus ciliaris and Chrysopogon plumulosus, which the zebra's eat for most of their food.[26][27]

References

- ↑ Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 631–632. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moehlman, P.D.; Rubenstein, D.I. & Kebede, F. (2008). "Equus grevyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 10 April 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is endangered.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Prothero D.R; Schoch R. M (2003). Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals'. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 216–18. ISBN 0-801-87135-2.

- 1 2 Vilstrup, Julia T.; et al. (2013). "Mitochondrial Phylogenomics of Modern and Ancient Equids". PLoS ONE. 8 (2): e55950. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055950.

- ↑ Forstén, Ann (1992). "Mitochondrial‐DNA timetable and the evolution of Equus: of molecular and paleontological evidence" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici. 28: 301–309.

- ↑ Ryder, O. A.; George, M. (1986). "Mitochondrial DNA evolution in the genus Equus". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 3 (6): 535–546.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Estes, R. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. University of California Press. pp. 240–242. ISBN 0-520-08085-8.

- ↑ J. E. Cordingley; S. R. Sundaresan; I. R. Fischhoff; B. Shapiro; J. Ruskey; D. I. Rubenstein (2009). "Is the endangered Grevy's zebra threatened by hybridization?" (PDF). Animal Conservation. 12 (6): 505–13. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00294.x.

- ↑ Huffman, B. "Grevy's zebra". Ultimate Ungulate.

- ↑ Grevy's zebra, Arkive

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kingdon, J. (1988). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part B: Large Mammals. University of Chicago Press. pp. 147–61. ISBN 9780226437224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Churcher C.S. (1993). "Equus grevyi" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 453: 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504222.

- ↑ Egri, Ádám; Blahó, Miklós; Kriska, György; Farkas, Róbert; Gyurkovszky, Mónika; Åkesson, Susanne; Horváth, Gábor (2012). "Polarotactic tabanids find striped patterns with brightness and/or polarization modulation least attractive: an advantage of zebra stripes". J Exp Biol. 215: 736–745. doi:10.1242/jeb.065540.

- ↑ How, Martin J.; Zanker, Johannes M. (2014). "Motion camouflage induced by zebra stripes". Zoology. 117: TBA. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2013.10.004.

- 1 2 Sundaresan, Siva R.; Fischhoff, Ilya R.; Hartung, Helen M.; Akilong, Patrick; Rubenstein, Daniel I. (2008). "Habitat choice of Grevy's zebras (Equus grevyi) in Laikipia, Kenya". African Journal of Ecology. 46 (3): 359–64. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00848.x.

- ↑ Bauer, I. E.; McMorrow, J.; Yalden, D. W. (1994). "The historic ranges of three equid species in North-East Africa: a quantitative comparison of environmental tolerances". Journal of Biogeography. 21 (2): 169–182. doi:10.2307/2845470. JSTOR 2845470.

- ↑ Youth, H. (2004). "Thin Stripes on a Thin Line". Zoogoer. 33 (November/December 2004). Archived from the original on 26 October 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Becker, C. D.; Ginsberg, J. R. (1990). "Mother-infant behaviour of wild Grevy's zebra". Animal Behavior. 40 (6): 1111–1118. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80177-0.

- ↑ Muoria. P. K.; Muruthi. P; Rubenstein. D; Oguge N. O; Munene E. (2005). "Cross-sectional survey of gastro-intestinal parasites of Grevy's zebras in southern Samburu, Kenya" (PDF). African Journal of Ecology. 43 (4): 392–95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2005.00588.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ginsberg, J.R.; Rubenstein, D.I. (1990). "Sperm competition and variation in zebra mating behavior" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 26 (6): 427–34. doi:10.1007/BF00170901.

- 1 2 Rubenstein, D. I. (2010) "Ecology, social behavior, and conservation in zebras". Pp. 231-58. In: Advances in the Study Behavior: Behavioral Ecology of Tropical Animals, Vol. 42. R. Macedo, ed. Elsevier Press. ISBN 0123808944

- ↑ Sundaresan, S. R.; Fischhoff, I. R.; Rubenstein, D. (2007). "Male harassment influences female movements and associations in Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi)" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology. 18 (5): 860–65. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm055.

- ↑ Rubenstein, D.I. (1986). "Ecology and sociality in horses and zebras" (PDF). In D. I. Rubenstein; R. W. Wrangham. Ecological Aspects of Social Evolution. Princeton University Press. pp. 282–302. ISBN 0691084394. JSTOR j.ctt7zvwgq.

- 1 2 3 Moelman, P.D (2002). "Status and Action Plan for the Grévy's Zebra (Equus grevyi) by Stuart D. Williams". Equids. Zebras, Assess and Horses. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan'. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. pp. 11–27. ISBN 2-831-70647-5.

- ↑ "Grevy's Zebra". Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ Platt, John R. "Devil Tree Threatens the World's Rarest Zebras". Retrieved 2015-08-07.

- ↑ Kebede, Almaz T.; Layne Coppock, D. "Livestock-Mediated Dispersal of Prosopis juliflora Imperils Grasslands and the Endangered Grévy's Zebra in Northeastern Ethiopia". Rangeland Ecology & Management. 68: 402–407. doi:10.1016/j.rama.2015.07.002.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grévy's zebra. |

- "Wildlife Grévy's Zebra" – summary from the African Wildlife Foundation

- Images and footage of Grévy's zebra from ARKive.org

- "To Catch a Zebra" by Brian Jackman – story of catching endangered Grévy's zebra for relocation

- "Why are the Grevy's Zebras in Trouble?" – Rich Blundell reports from Kenya

- Grevy's Zebra Trust – a Kenyan organization dedicated to preserving the Grévy's zebra