HMT Dunera

| History | |

|---|---|

| Builder: | Barclay Curle & Company, Glasgow |

| Launched: | 10 May 1937 |

| In service: | 25 August 1937 |

| Out of service: | 1967 |

| Homeport: | London |

| Fate: | scrapped 1967, Bilbao |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Troopship, educational cruise ship |

| Tonnage: | 11,161 GRT; 6 634 NRT; 3,819 tonnes deadweight (DWT) |

| Length: | 516 ft 10 in (157.53 m) |

| Beam: | 63 ft 3 in (19.28 m) |

| Draught: | 23 ft 5 in (7.14 m) |

| Propulsion: | Two five cylinder 2SCSA Doxford-type opposed piston oil engines, 11,880 bhp, twin screws, |

| Speed: | 16 knots |

| Capacity: | 104 1st Class, 100 2nd Class & 164 3rd Class passengers or 1,157 troops. |

HMT Dunera was a British passenger ship built as a troopship in the late 1930s. She was also a passenger liner and an educational cruise ship. Dunera saw extensive service throughout the Second World War.

After trials in 1937, she was handed over to the British-India Steam Navigation Company. In 1939 Dunera gave schools cruises.

War service

Dunera carried New Zealand troops to Egypt in January 1940.

The Dunera Boys

Through her next deployment Dunera lent her name to one of the more notorious events of British maritime history. After the fall of France men of German and Austrian origin in Britain were rounded up as a precaution. The intention had been to segregate those who might pose a risk to security from those who were neutral or who had fled to Britain to escape from Nazism. But in a wave of xenophobia such distinctions became lost. In what Winston Churchill later regretted as "a deplorable and regrettable mistake,” they were all suspected of being German agents, potentially helping to plan the invasion of Britain, and a decision was made to deport them.

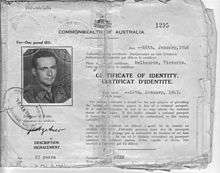

On 10 July 1940, 2,542 detainees, all classified as “enemy aliens," were embarked aboard Dunera at Liverpool. They included 200 Italian and 251 German prisoners of war, as well as several dozen Nazi sympathizers, along with 2,036 anti-Nazis, most of them Jewish refugees. Some had already been to sea but their ship, the Arandora Star,[1] had been torpedoed with great loss of life. In addition to the passengers were 309 poorly trained British guards, mostly from the Pioneer Corps, as well as seven officers and the ship’s crew, creating a total complement of almost twice the Dunera’s capacity as a troop carrier of 1,600.[2]

The internees' possessions were rifled and subsequently the UK government paid ₤35,000 to the Dunera victims in compensation. Moreover, the 57-day voyage was made under the risk of enemy attack. But it was the physical conditions and ill-treatment that were most deplorable. Internees were frequently abused, beaten, and robbed by the guards, whose sergeants would take men into the ship's head for private beatings. Most internees were kept below decks throughout the voyage, except for daily 10-minute exercise periods, during which internees would walk around the deck under heavy guard; during one such period, a guard smashed beer bottles on the deck so that the internees would have to walk on the shards. In contrast to the Army personnel, the ship's crew and officers showed kindness to the internees, and some later testified at the soldiers' courts-martial.

“The ship was an overcrowded Hell-hole. Hammocks almost touched, many men had to sleep on the floor or on tables. There was only one piece of soap for twenty men, and one towel for ten men, water was rationed, and luggage was stowed away so there was no change of clothing. As a consequence, skin diseases were common. There was a hospital on board but no operating theatre. Toilet facilities were far from adequate, even with makeshift latrines erected on the deck and sewage flooded the decks. Dysentery ran through the ship. Blows with rifle butts and beatings from the soldiers were daily occurrences. One refugee tried to go to the latrines on deck during the night – which was out-of-bounds. He was bayoneted in the stomach by one of the guards and spent the rest of the voyage in the hospital."[3]

While passing through the Irish sea, the Dunera was struck by a torpedo that failed to detonate; a second torpedo passed underneath the vessel, which was lifted out of its path by the rough seas.[4]

Among the transportees on the Dunera were Franz Stampfl, later the athletics coach to the four-minute-mile runner Roger Bannister, Wolf Klaphake, the inventor of synthetic camphor, the tenor Erich Liffmann, composer Ray Martin (orchestra leader),[5] artists Heinz Henghes, Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack and Erwin Fabian, art historians Franz Phillipp and Ernst Kitzinger, artist Johannes Koelz, the photographers Henry Talbot and Hans Axel, author Ulrich Boschwitz (who wrote under the pen name John Grane),[6] and furniture designers Fred Lowen and Ernst Roedeck. Also on board were theoretical physicist Hans Buchdahl and his engineer (later philosopher) brother Gerd; Alexander Gordon (Abrascha Gorbulski) who appeared in the documentary Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport, Walter Freud grandson of Sigmund Freud, Engineering Professor at Imperial College,Paul Eisenklam, and Professor Hugo Wolfsohn, a prominent political scientist .[7]

The television movie The Dunera Boys depicts their experiences,[8] as do several books and websites.[9]

On arrival in Sydney on 6 September 1940, the first Australian on board was medical army officer Alan Frost. He was appalled and his subsequent report led to the court martial of the officer in charge, Lieutenant-Colonel William Scott.[10] Scott was “severely reprimanded” as was Sgt Helliwell. RSM Bowles was reduced to the ranks and given a twelve-month prison sentence and then discharged from the British Army. After leaving the Dunera the pale and emaciated refugees were transported through the night by train 750 kilometres (470 mi) west of Sydney to the rural town of Hay in central New South Wales. “The treatment on the train was in stark contrast to the horrors of the Dunera – the men were given packages of food and fruit, and Australian soldiers offered them cigarettes. There was even one story of a soldier asking one of the internees to hold his rifle while he lit his cigarette."[3]

Back in Britain relatives had not at first been told what had happened to the internees, but as letters arrived from Australia there was a clamour to have them released and heated exchanges in the House of Commons. Colonel Victor Cazalet, a Conservative MP said, on 22 August 1940: "Frankly I shall not feel happy, either as an Englishman or as a supporter of this government, until this bespattered page of our history has been cleaned up and rewritten.” While interned in Australia, the internees set up and administered their own township with Hay currency (which is now a valuable collectors’ item) and an unofficial "university." When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the prisoners were reclassified as "friendly aliens" and released by the Australian Government. Hundreds were recruited into the Australian Army and about a thousand stayed when offered residency at the end of the war. Almost all the rest made their way back to Britain, many of them joining the armed forces there. Others were recruited as interpreters or into the intelligence services.

Nothing remains of Hay camp except a road called Dunera Way and a memorial stone which reads:

This plaque marks the 50th anniversary of the arrival from England of 1,984 refugees from Nazi oppression, mistakenly shipped out on HMT Dunera and interned in Camps 7 & 8 on this site from 7. 9. 1940 to 20. 5. 1941. Many joined the AMF on their release from internment and made Australia their homeland and greatly contributed to its development. Donated by the Shire of Hay – September 1990.

Later service

HMT Dunera's next notable services were the Madagascar operations in September 1942, the Sicily landings in July 1943 and in September 1944, she carried the headquarters staff for the US 7th Army for the invasion of southern France. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Dunera transported occupation forces to Japan.

Post-war

In 1950/1951, Dunera was refitted by Barclay, Curle to improve her to postwar troopship specifications: her capacity was now 123 First Class, 95 Second Class, 100 Third Class and 831 troops; tonnages now 12,615 gross, 7,563 net and 3,675 tons deadweight.

The Ministry of Defence terminated Dunera's trooping charter in 1960 and she was refitted by Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company at Hebburn-on-Tyne in early 1961 for her new role as an educational cruise ship.[11] New facilities (classrooms, swimming pool, games rooms, library and assembly rooms) were introduced. Her capacity became 187 cabin passengers and 834 children; 12,620 GRT, 7,430 NRT.

In November 1967 she was sold to Revalorizacion de Materiales SA, and scrapped at Bilbao.

Notes and references

- ↑ "Maritime Disasters of World War II". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Robert Aufrichtig – Dunera Internee". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- 1 2 http://www.marple-uk.com/misc/dunera.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/10409026

- ↑ Die verschwundenen musiker : Jüdische flüchtlinge in Australien by Albrecht Dümling (Böhlau Verlag, 2011).

- ↑ Guide to the Ulrich Boschwitz (1915-1942) Collection, at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ "Into The Arms Of Strangers". .warnerbros.com. Retrieved 2014-05-03.

- ↑ "The Dunera Boys synopsis". IMDB. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "MS Dunera, Troop Ship To School Ship | Wartime Trips and School Educational Tours". Dunera.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-05-03.

- ↑ Connolly, Kate (19 May 2006). "Britons finally learn the dark Dunera secret". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Educational Cruises were operated by the British India Steam Navigation Company in the 1960s and 1970s, to take school children from British colonies or member countries of the Commonwealth on educational tours in European waters, lasting usually a fortnight. [Quartermaine, P., Bruce, P. Cruise: identity, design and culture. Laurence King Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-85669-446-1. p. 49]

External links

- Shipping Times

- The Dunera Boys at IMDb.

- HMT Dunera, Troop Ship to School Ship: Wartime Trips and School Educational Tours