Hamida Banu Begum

| Hamida Banu Begum Mariam Makani | |

|---|---|

Hamida Banu Begum | |

| Empress mother of Mughal | |

| Tenure | 27 January 1556 - 29 August 1604 |

| Empress consort of Mughal | |

| Tenure | 22 February 1555 – 27 January 1556 |

| Born |

21 April 1524 Paat, Dadu District Sindh |

| Died |

29 August 1604 (aged 80) Agra, Mughal Empire |

| Burial |

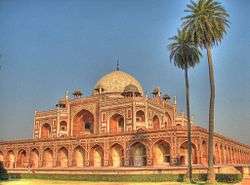

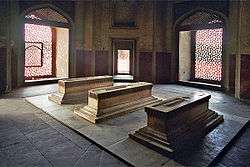

30 August 1604 Humayun's Tomb, Delhi |

| Spouse | Humayun |

| Issue | Akbar |

| Father | Shaikh Ali Akbar Jami |

| Mother | Mahna Afroz Begum |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

Hamida Banu Begum, she was the given the title Mariam Makani[1] (1527 – 29 August 1604, Persian: حمیدہ بانو بیگم, translit. Ḥamīda Banū Begum) was a wife of the second Mughal Emperor, Humayun, and the mother of Mughal Emperor, Akbar.[2] She built Humayun's mausoleum by a mix of Persian and Hindustani artisans.[3]

Family

Hamida Banu Begum was born in 1524 to Shaikh Ali Akbar Jami, a Persian Shia, and a friend and preceptor to Mughal prince Hindal Mirza, the youngest son of the first Mughal Emperor Babar. Ali Akbar Jami was also known as Mian Baba Dost, who belonged to the lineage of Ahmad Jami Zinda-fil. Hamida Banu's mother was Mahna Afraz Begum, who married Ali Akbar Jami in Paat, Sindh. As suggested by her lineage, Hamida was a devout Muslim.[4]

Meeting with Humayun

She met Humayun, as a seventeen-year-old girl and frequenting Mirza Hindal's household, at a banquet given by Dildar Begum, Babar's wife and Humayun's stepmother in Alwar. Humayun was in exile after his exodus from Delhi, due to the armies of Sher Shah Suri, who had ambitions of restoring Afghan rule in Delhi.[5]

When negotiations for Humayun's marriage with Hamida Banu Begum were going on, both Hamida and Hindal vehemently opposed the marriage proposal, possibly because they were involved with each other.[6] It is seems probable that Hamida was in love with Hindal, though there is only circumstantial evidence for it.[6] In her book, the Humayun-nama, Hindal's sister and Hamida's close friend, Gulbadan Begum, pointed out that Hamida was frequently seen in Hindal's palace during those days, and often attended parties organized by their mother, Dildar Begum.[7]

Initially, Hamida refused to meet the Emperor, eventually after forty days of pursuit and at the insistence of Dildar Begum, she agreed to marry him. She refers to her initial reluctance in her book the Humayunama,

| “ | I shall marry someone; but he shall be a man whose collar my hand can touch, and not one whose skirt it does not reach." | ” |

Marriage

The marriage took place on a day chosen by the Emperor, an avid astrologer, himself employing his astrolabe, at mid-day on a Monday in September, 1541 (Jumada al-awwal 948 AH) at Patr (known as Paat, Dadu District of Sindh). Thus she became his junior wife, after Bega Begum (later known as Haji Begum, after Hajji), who was his first wife and chief consort.[2][9][10] Hamida Banu Begum is also known as Maryam Makani. The marriage became "politically beneficial" to Humayun as he got help from the rival Shia groups during times of war.[8]

Two years later, after a perilous journey through the desert, on 22 August 1542, she and Emperor Humayun reached at the Umerkot ruled by Rana Prasad, a Hindu Sodha Rajput, at a small desert town, and the Rana gave them asylum. Two months later she gave birth future Emperor, Akbar on the early morning of 15 October 1542 (fourth day of Rajab, 949 AH), he was given the name Humayun had heard in his dream at Lahore – the Emperor Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar[11][12][13][14][15]

In coming years, she took on numerous tough journeys to follow her husband, who was still in flight. First the beginning of the following December she and her new born went into camp at Jūn, after traveling for ten or twelve days. Then in 1543, she made the perilous journey from Sindh, which had Qandahar for its goal, but in course of which Humayun had to take hasty flight from Shal-mastan, ‘through a desert and waterless waste.’ Leaving her little son behind, she accompanied her husband to Persia, here they visited the shrines of her ancestor, Ahmad-e Jami and Shiites shrine, of Ardabil in Iran, the place of origin of Safavid dynasty which helped them immensely in the following years . In 1544, at a camp at Sabzawar, 93 miles south of Herat, she gave birth to a daughter, thereafter she returned from Persia with the army given to Humayun by Shah of Iran, Tahmasp I, and at Kandahar met Dildar Begum, and her son, Mirza Hindal. Thus, it was not until 15 November 1545 (Ramdan 10th, 952 AH) that she saw her son Akbar again, the scene of young Akbar recognizing his mother amongst a group of women has been keenly illustrated in Akbar's biography, Akbarnama. In 1548, she and Akbar accompanied Humayun to Kabul.[15]

Mughal Empress

During the reign of Akbar, there are many instances where, imperial ladies interfered in matters of the court to ask pardon for a wrong doer. Though once Hamida Banu did so, her pleas went to deaf ears as Akbar refused to forgive a Sunni Muslim from Lahore who killed a Shia Muslim.[16]

Empress dowager

Meanwhile, Sher Shah Suri died in May 1545, and after that his son and successor, Islam Shah died too in 1554, disintegrating the Suri dynasty rule. In November 1554, when Humayun set out for India, she stayed back in Kabul. Though he took control of Delhi in 1555, he died within a year of his return, by falling down the steps of his library at Purana Qila, Delhi, in 1556 at the age of 47, leaving behind a thirteen-year-old heir, Akbar, who was to become one of greatest emperors of the empire. Hamida Banu joined Akbar from Kabul, only during his second year of reign, 1557 CE, and stayed with him thereafter, she even intervened into politics on various occasions, most notable during the ouster of Mughal minister, Bairam Khan, when Akbar came of age in 1560.[15]

Death and aftermath

She was buried at Humayun's Tomb after her death on 29 August 1604 (19th Shahriyar, 1013 AH) in Agra, just a year before the death of her son Akbar and almost half a century after death of her husband, Humayun. Throughout her years, she was held in high regard by her son Akbar, as English traveler Thomas Coryat recorded, Akbar carrying her palanquin himself across the river, during one of her journeys from Lahore to Agra. Later when Prince Salim, future emperor Jahangir, revolted against his father Akbar, she took upon the case of her grandson, and a reconciliation ensued thereafter, even though Salim had plotted and got Akbar's favorite minister Abu'l-Fazl killed. Akbar shaved his head and chin only on two occasions, one at the death of foster-mother Jiji Anga and another at the death of his mother.[17][18][19]

She was given the title, Maryam-makānī, dwelling with Mary, posthumously, as she was considered, 'epitome of innocence' by Akbar.[20] Details of her life are also found in Humayun Nama, written by Gulbadan Begum, sister of Humayun,[21][22] as well as in Akbarnama and Ain-i-Akbari, both written during the reign of his son, Akbar.

In popular culture

In Jodhaa Akbar, a 2008 Indian epic film, directed by Ashutosh Gowariker, the character of Hamida Bano was portrayed by Poonam Sinha.[23] Previously in Hindi epic film Humayun (1945) directed by Mehboob Khan, her role was portrayed by actor, Nargis[24]

Further reading

- Humayun-Nama : The History of Humayun by Gulbadan Begum, Tr. by Annette S. Beveridge (1902). New Delhi, Goodword, 2001. ISBN 81-87570-99-7.E-book at Packard Institute Excerpts at Columbia Univ.

- Begam Gulbadam; Annette S. Beveridge. The history of Humayun = Humayun-nama. Begam Gulbadam. pp. 249–. GGKEY:NDSD0TGDPA1.

- Mukhia, Harbans (2004). The Mughals of India. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780631185550.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hamida Banu Begum. |

- ↑ Mukhia 2004, p. 125.

- 1 2 The Humayun Nama: Gulbadan Begum's forgotten chronicle Yasmeen Murshed, The Daily Star, 27 June 2004.

- ↑ Tankha, Madhur (June 6, 2014). "Bringing it back to glory". The Hindu.

- ↑ Dr. B. P. Saha. Begams, concubines, and memsahibs. Vikas Pub. House. p. 20.

- ↑ Mukherjee, p.119

- 1 2 Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne : The Saga of the Great Mughals ([Rev. ed.]. ed.). Penguin books. pp. 65, 526. ISBN 9780141001432.

- ↑ Wade, Bonnie C. (1998). Imaging Sound : an Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art, and Culture in Mughal India. Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780226868417.

- 1 2 Mukherjee, p.120

- ↑ Nasiruddin Humayun The Muntakhabu-’rūkh by Al-Badāoni, Packard Humanities Institute.

- ↑ Bose, Mandakranta (2000). Faces of the feminine in ancient, medieval, and modern India. US: Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-19-512229-1. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ↑ Part 10:..the birth of Akbar Humayun nama by Gulbadan Begum.

- ↑ Conversion of Islamic and Christian dates (Dual) As per the date converter Akbar's birth date, as per Humayun nama, of 04 Rajab, 949 AH, corresponds to 14 October 1542.

- ↑ Amarkot Genealogy Queensland University.

- ↑ Akbar, Jellaladin Mahommed

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press..

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.. - 1 2 3 Schimmel, Annemarie; Burzine K. Waghmar (2004). The empire of the great Mughals. Reaktion Books. p. 146. ISBN 1-86189-185-7..

- ↑ Mukherjee, p.130

- ↑ Genealogy of Hamida Begum

- ↑ Mukhia, Harbans (2004). The Mughals of India. India: Wiley. p. 115. ISBN 81-265-1877-4.

- ↑ Hamida Banu Faces of the feminine in ancient, medieval, and modern India, by Mandakranta Bose. Oxford University Press US, 2000. ISBN 0-19-512229-1. Page 203.

- ↑ Mausoleum that Humayun never built The Hindu, 28 April 2003.

- ↑ Humayun-Nama : The History of Humayun by Gul-Badan Begam. Translated by Annette S. Beveridge. New Delhi, Goodword, 2001,ISBN 81-87570-99-7. Page 149.

- ↑ LXXXIII. Ḥamīda-bānū Begam Maryam-makānī Humayun-nama Chapter 57, Appendix A. Biographical Notices of the Women mentioned by Babar, Gulbadan Begum, and Haidar.LXXXIII.. Packard Humanities Institute

- ↑ Jodhaa Akbar at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Humayun at the Internet Movie Database. On 18 June 2013, Zee TV started airing a TV series titled Jodhaa Akbar with Rajat Tokas and Paridhi Sharma in the lead. Hamida Banu Begum is portrayed as a main character and is played by Chhaya Phadkar