Harem

Harem (Arabic: حريم ḥarīm, "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family"),[1][2] also known as zenana in South Asia, properly refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family and are inaccessible to adult males except for close relations.[3][4][5] Similar institutions have been common in other Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilizations, especially among royal and upper-class families,[4] and the term is sometimes used in non-Islamic contexts.[6] The structure of the harem and the extent of monogamy or polygamy has varied depending on the family's personalities, socio-economic status, and local customs.[3] This private space has been traditionally understood as serving the purposes of maintaining the modesty, privilege, and protection of women.[3] A harem may house a man's wife — or wives and concubines, as in royal harems of the past — their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic workers, and other unmarried female relatives.[3] In former times, some harems were guarded by eunuchs who were allowed inside.[3] Although the institution has experienced a decline in the modern era, the spatial seclusion of female family members from male visitors to the house is still practiced in many parts of the Muslim world.[3] In the West, Orientalist imaginary conceptions of the harem, as a personal brothel where numerous women lounged in suggestive poses, have influenced culture and to certain extent relationship with Islamic societies through many paintings, music, stage productions, films and literary works,[3][4] and the word has become particularly associated with polygyny and large royal harems.

Etymology

.jpg)

The word has been recorded in the English language since early 17th century.[2] It comes from the Arabic ḥarīm, which can mean "a sacred inviolable place", "harem" or "female members of the family".[1][2] The triliteral Ḥ-R-M appears in other terms related the notion of interdiction such as haram (forbidden), mahram (unmarriageable relative), ihram (a pilgrim's state of ritual consecration during the Hajj) and al-Ḥaram al-Šarīf ("the noble sanctuary", which can refer to the Temple Mount or the sanctuary of Mecca).[1][4]

The word is a cognate of Hebrew ḥerem, rendered in Greek as anathema when it applies to excommunication pronounced by the Jewish Sanhedrin court. All these words mean that an object is "sacred" or "accursed".

In Turkish of the Ottoman era, the harem, i.e., the part of the house reserved for women was called haremlık, while the space open for men was known as selamlık.[7]

History

The word harem is strictly applicable to Muslim households only, but the system was common, more or less, to most ancient Oriental communities, especially where polygamy was permitted.[8]

The Imperial Harem of the Ottoman sultan, which was also called seraglio in the West, typically housed several dozen women, including wives. It also housed the sultan's mother, daughters and other female relatives, as well as eunuchs and slave servant girls to serve the aforementioned women. During the later periods, the sons of the sultan lived in the Harem until they were 12 years old,[9] when it was considered appropriate for them to appear in the public and administrative areas of the palace. The Topkapı Harem was, in some senses, merely the private living quarters of the sultan and his family, within the palace complex. Some women of Ottoman harem, especially wives, mothers and sisters of sultans, played very important political roles in Ottoman history, and in times it was said that the empire was ruled from harem. Hürrem Sultan (wife of Suleiman the Magnificent, mother of Selim II), was one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history.

It is being more commonly acknowledged today that the purpose of harems during the Ottoman Empire was for the royal upbringing of the future wives of noble and royal men. These women would be educated so that they were able to appear in public as a royal wife.[10]

In the Ottoman period before Atatürk's Reforms, "harem", more properly (Turk.) haremlik, meant simply the private or family area of a typical upper-class household, as opposed to the public or reception rooms known as the selamlik.[11]

Sultan Ibrahim the Mad, Ottoman ruler from 1640 to 1648, is said to have drowned 280 concubines of his harem in the Bosphorus.[12] At least one of his concubines, Turhan Hatice, a Ukrainian who was captured during one of the raids by Tatars and sold into slavery, survived his reign.

The harem was not just a place where women lived. Babies were born and children grew up there. Within the precincts of the harem were markets, bazaars, laundries, kitchens, playgrounds, schools and baths. The harem had a hierarchy, its chief authorities being the wives and female relatives of the emperor and below them were the concubines.[13] There was mother, step-mothers, aunts, grandmothers, step-sisters, sisters, daughters and other female relatives that lived in the harem. There were also ladies-in-waiting, servants, maids, cooks, women official and guards.[14]

In Istanbul, the separation of men's and women's quarters were never practiced among the poor, and by 1920s and 1930s it had become a thing of the past in middle- and upper-class homes.[15]

Outside Islamic culture

Ancient Egyptian pharaohs are said to have made a "constant demand" on provincial governors for more beautiful servant girls.

King Kashyapa of Sigiriya in Sri Lanka had as many as 500 women of the harem (Orodha). They are depicted in the Sigiriya Frescoes and referred to in graffiti on the Mirror Wall there. The harem consisted of concubines and female members of the royal court. It was considered an honour to be a "lady of the king's harem".[16]

In Mexico, Aztec ruler Montezuma II, who met Cortes, kept 4,000 concubines; every member of the Aztec nobility was supposed to have had as many consorts as he could afford.[17]

Harem is also the usual English translation of the Chinese language term hougong (hou-kung; Chinese: 後宮; literally: "the palace behind"). Hougong refers to the part of the palace reserved for the Chinese emperor's consorts, concubines, female attendants and eunuchs. Chinese palaces were divided into a working part in which the Emperor would meet ministers, govern and carry out religious rites. Behind this public part were the private apartments of the Emperor and his consorts. The women who lived in an emperor's hougong sometimes numbered in the thousands. In 1421, the Yongle Emperor ordered 2,800 concubines, servant girls and eunuchs who guarded them to a slow slicing death as the Emperor tried to suppress a sex scandal which threatened to humiliate him.[18] Taking multiple concubines was a means to display wealth and power; and outside of the nobility harems were maintained by high-ranking officials and rich merchants. The government official Heshen had 600 women in his harem.[19]

A similar institution existed among the Ōoku during the Edo period in Japan.

Some African royal and noble lineages also have long traditions of polygyny. During the colonization of Africa, the junior wives and concubines of the native chieftains were often collectively referred to as their harems by colonial officials. Although the ritually superior great wives in these cases – consorts in the traditionally Western sense who were often the earliest of them to have been married – were usually vested with powers that made them distinct when compared to their fellow spouses, they were often considered by the colonialists to be members of the harems. In modern African polygynous cases, as in that of the royal family of the King of Swaziland, the word is generally avoided due to socio-linguistic political correctness, although it is technically correct to refer to a group of women married to a single tribal chief in this manner.

Western representations

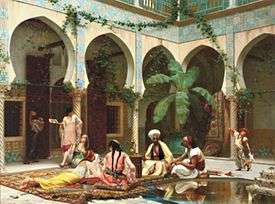

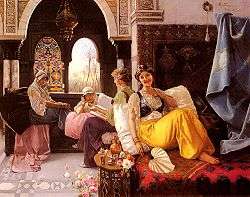

The institution of the harem exerted a certain fascination on the European imagination, especially during the Age of Romanticism, and was a central trope of Orientalism in the arts, due in part to the writings of the adventurer Richard Francis Burton. Images through paintings and later films were particularly powerful ways of expressing these tropes. Many Westerners falsely imagined a harem as a personal brothel consisting of many sensual young women lying around pools with oiled bodies, with the sole purpose of pleasing the powerful man to whom they had given themselves. Much of this fantasy is recorded in Western art from that period, usually portraying groups of attractive women lounging nude by spas and pools.

A centuries-old theme in Western culture is the depiction of European women forcibly taken into Oriental harems – evident for example in the Mozart opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail ("The Abduction from the Seraglio") concerning the attempt of the hero Belmonte to rescue his beloved Konstanze from the seraglio/harem of the Pasha Selim; or in Voltaire's Candide, in chapter 12 of which the old woman relates her experiences of being sold into harems across the Ottoman Empire.

Much of Verdi's opera Il corsaro takes place in the harem of the Pasha Seid - where Gulnara, the Pasha's favorite, chafes at life in the harem, and longs for freedom and true love. Eventually she falls in love with the dashing invading corsair Corrado, kills the Pasha and escapes with the corsair - only to discover that he loves another woman.

The Lustful Turk, a well-known British erotic novel, was also based on the theme of Western women forced into sexual slavery in the harem of the Dey of Algiers, while in A Night in a Moorish Harem, a Western man is invited into a harem and enjoys forbidden sex with nine concubines. In both works, the theme of "West vs. Orient" is clearly interwoven with the sexual themes.

The Sheik novel and the Sheik film, a Hollywood production from 1921, are both controversial and probably the best known works created by exploiting the motive.[20] Much criticism ensued over decades, especially recently, on various strong and unambiguous Orientalist and colonialist elements, and in particularly directed at ideas closely related to the central rape plot in which for women, sexual submission is a necessary and natural condition, and that interracial love between an Englishwoman and Arab, a "native", is avoided, while the rape is ultimately justified by having the rapist turn out to be European rather than Arab.[21][22][23][24]

Image gallery

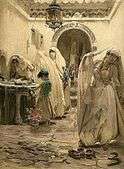

Many Western artists have depicted their imaginary conceptions of the harem.

- Depictions of Harems

The Pasha in His Harem by Francois Boucher c. 1735-1739

The Pasha in His Harem by Francois Boucher c. 1735-1739 Scene from the Harem, Jean-Baptiste van Mour (1st half of the 18th century)

Scene from the Harem, Jean-Baptiste van Mour (1st half of the 18th century) Scene in a Harem, by Guardi

Scene in a Harem, by Guardi The Harem as imagined by European artist, The Dormitory of the Concubines, by Ignace Melling, 1811.

The Harem as imagined by European artist, The Dormitory of the Concubines, by Ignace Melling, 1811. Gustave Boulanger: The Harem

Gustave Boulanger: The Harem Harem scene by Dominique Ingres

Harem scene by Dominique Ingres The Reception, John Frederick Lewis, 1805-1875, English

The Reception, John Frederick Lewis, 1805-1875, English Scene from the Harem by Fernand Cormon, c. 1877

Scene from the Harem by Fernand Cormon, c. 1877 Harem dance by Giulio Rosati

Harem dance by Giulio Rosati Harem Scene, Quintana Olleras, 1851-1919, Spanish

Harem Scene, Quintana Olleras, 1851-1919, Spanish The Harem Fountain, Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1847-1928, American

The Harem Fountain, Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1847-1928, American Belle of Nelson whiskey poster (1878), based on a harem scene by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Belle of Nelson whiskey poster (1878), based on a harem scene by Jean-Léon Gérôme. In the harem, Lehnert & Landrock postcard, 1900s-1910s

In the harem, Lehnert & Landrock postcard, 1900s-1910s_-_Ad_6.jpg) The Virgin of Stamboul, 1920 film poster

The Virgin of Stamboul, 1920 film poster.jpg) Harem in Italian film Era lui, sì, sì! (1951)

Harem in Italian film Era lui, sì, sì! (1951)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Hans Wehr, J. Milton Cowan (1976). A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (3rd ed.). Spoken Language Services. pp. 171–172.

- 1 2 3 Harem at WordReference.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cartwright-Jones, Catherine (2013). "Harem". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 Anwar, Etin (2004). "Harem". In Richard C. Martin. Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.

- ↑ Harem in Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- ↑ Elfriede Haslauer (2005). "Harem". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Donald Quataert (2005). The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922. Cambridge University Press. p. 152.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Harem". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Harem". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Ansary, Tamim (2009). Destiny disrupted: a history of the world through Islamic eyes. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 228. ISBN 9781586486068.

- ↑ Goodwin, Godfrey (1997). The private world of Ottoman women. London: Saqi Books. p. 127. ISBN 9780863567513.

- ↑ Bridge, Ann (1937). Enchanter's Nightshade.

- ↑ Dash, Mike (22 March 2012). "The Ottoman Empire's Life-or-Death Race". Smithsonian.com.

- ↑ Sharma, Anjali (28 November 2013). "Inside the harem of the mughals". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal ladies and their contributions. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 9788121207607.

- ↑ Alan Duben, Cem Behar (2002). Istanbul Households: Marriage, Family and Fertility, 1880-1940. Cambridge University Press. p. 223.

- ↑ Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). Story of Sigiriya. Melbourne: Panique Pty Ltd. ISBN 978-0987345110.

- ↑ Betzig, Laura (March 1994). "Sex in History". Michigan Today. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013.

- ↑ "Revenge of the evil emperor: Mass slaughter in Beijing's Forbidden City". Mail Online. 3 May 2008.

- ↑ Wang, William (15 April 2014). "Visitors Flock to House of China's Most Corrupt Official". CRI English.

- ↑ "The Sheik". University of Pennsylvania Press website. Accessed Oct. 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Sheiks & Terrorists - Reclaiming Identity: Dismantling Arab Stereotypes". www.arabstereotypes.org. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ J., Dajani, Najat Z. (1 January 2000). "Arabs in Hollywood : Orientalism in film". doi:10.14288/1.0099552. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Hsu-Ming Teo. ""Historicizing The Sheik: Comparisons of the British Novel and the American Film"". jprstudies.org. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Hsu-Ming Teo. "Desert Passions: Orientalism and Romance Novels".

Further reading

- Alev Lytle Croutier. Harem: The World Behind the Veil, reprint ed. Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.), 1998. ISBN 1-55859-159-1

- Alan Duben, Cem Behar, Richard Smith (Series Editor), Jan De Vries (Series Editor), Paul Johnson (Series Editor), Keith Wrightson (Series Editor). Istanbul Households: Marriage, Family and Fertility, 1880-1940, new ed. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-52303-6

- John Freely. Inside the Seraglio: Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul: The Sultan's Harem, new ed. Penguin (Non-Classics), 2001. ISBN 0-14-027056-6

- Lal, Kishori Saran (1988). The Mughal Harem. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-85179-03-4.

- Reina Lewis. Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel, And The Ottoman Harem. Rutgers University Press, 2004 ISBN 0813535433, 9780813535432

- Fatima Mernissi. Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood Perseus 1994

- Leslie P. Peirce. The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, new ed. Oxford University Press USA, 1993. ISBN 0-19-508677-5

- N. M. Penzer. The Harēm : Inside the Grand Seraglio of the Turkish Sultans. Dover Publications, 2005. ISBN 0-486-44004-4

- M. Saalih. Harem Girl : A Harem Girl’s Journal reprint ed. Delta, 2002. ISBN 0-595-31300-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harems. |

- Harem in the Ottoman Empire (English)

- Some paintings of harems

- Popular culture depictions of harems

- Harem Novel From Aslı Sancar

-

Godwin, Parke (1879). "Harem". The American Cyclopædia.

Godwin, Parke (1879). "Harem". The American Cyclopædia.