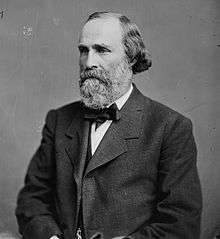

Henry L. Dawes

| Henry Laurens Dawes | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

|

In office March 4, 1875 – March 3, 1893 | |

| Preceded by | William B. Washburn |

| Succeeded by | Henry Cabot Lodge |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 11th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | Mark Trafton |

| Succeeded by | District eliminated until 1873 |

|

In office March 4, 1873 – March 3, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | District reissued in 1873 |

| Succeeded by | Chester W. Chapin |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 10th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1863 – March 3, 1873 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Delano |

| Succeeded by | Alvah Crocker |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1848-1849 1852 | |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate | |

|

In office 1850 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 30, 1816 Cummington, Massachusetts |

| Died |

February 5, 1903 (aged 86) Pittsfield, Massachusetts |

| Political party | Republican |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Henry Laurens Dawes (October 30, 1816 – February 5, 1903) was a Republican United States Senator and United States Representative, notable for the Dawes Act, intended to stimulate assimilation of Indians by ending tribal government and control of communal lands.

Life and career

Dawes was born in Cummington, Massachusetts in 1816. After graduating from Yale University in 1839, he taught at Greenfield, Massachusetts, and also edited The Greenfield Gazette. In 1842, he was admitted to the bar and began the practice of law at North Adams, where for a time he edited The North Adams Transcript.

In 1869 Dawes became a founding member of the Monday Evening Club, a men's literary society in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.[1] The post-Civil War period was one of founding numerous fraternal and civil societies.

Henry Dawes died in Pittsfield, Massachusetts on February 5, 1903.[2]

Political career

Dawes served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1848-1849 and in 1852, in the state Senate in 1850, and in the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1853.

From 1853 to 1857, he was United States district attorney for the western district of Massachusetts. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1856, serving until 1875. During this time, in 1868, he received 2,000 shares of stock in the Crédit Mobilier of America railroad construction company from Congressman Oakes Ames, as part of the Union Pacific railway's influence-buying efforts.

In late 1871 and early 1872, Dawes became an ardent supporter of the creation of Yellowstone National Park, in order to preserve its wilderness and resources. In March 1871, he supported federal financing for Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden's fifth geological survey of the territories, which became a driving force in the creation of the park. Dawes' son, Chester Dawes, was a member of the survey team, and Annie, the first commercial boat on Yellowstone Lake, was purportedly named after his daughter, Anna Dawes. When the Act of Dedication bill came before congress, Dawes was one of its most active supporters.[3]

In 1875, he was chosen by the state legislature to succeed William B. Washburn as U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, serving until 1893.

During this long period of legislative activity, Dawes served in the House on the committees on elections, ways and means, and appropriations. He took a prominent part in passage of the anti-slavery and Reconstruction measures during and after the Civil War, in tariff legislation, and in the establishment of a fish commission. He also initiated daily weather reports to be provided by the federal government.

In the Senate, Dawes was chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs. He concentrated on enactment of laws that he believed were for the benefit of the Indians. In the late 19th century, after the Indian Wars, there were widespread fears that the Indians were disappearing and that their tribes would cease.

Dawes' most prominent achievement in Congress was the passage in 1887 of the General Allotment Act of 1887 (Dawes Act), ch. 119, 24 Stat. 388, 25 U.S.C. § 331 et seq., which authorized the President of the United States to survey Indian tribal land and divide the area into allotments for the individual Indian or household. It was intended to assimilate Indians by breaking up their tribal governments and communal lands, and encouraging them in subsistence farming. It was enacted February 8, 1887, and named for Dawes, its sponsor. The Act was amended in 1891, 1898 by the Curtis Act, and in 1906, by the Burke Act.

The Dawes Commission, set up under an Indian Office appropriation bill in 1893, was created, not to administer the Act, but to attempt to persuade the tribes excluded under the Act because of treaties to agree to the allotment plan. It was this commission that registered the members of the Five Civilized Tribes and many Indian names appear on the rolls. The Curtis Act of 1898 extended the provisions of the Dawes Act to the Five Civilized Tribes, abolishing tribal jurisdiction of their communal lands.

On leaving the Senate in 1893, Dawes became chairman of the Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes (the Dawes Commission) and served in this capacity for ten years. He negotiated with the tribes for the extinction of the communal title to their land and for the dissolution of the tribal governments, with the object of making the tribes a constituent part of the United States. Native Americans lost about 90 million acres (360,000 km²) of treaty land, or about two-thirds of their 1887 land base, over the life of the Dawes Act. About 90,000 Indians were made landless. The Act forced Native people onto small tracts of land distant from their kin relations. The allotment policy depleted the land base and ended hunting as a means of subsistence, creating a crisis for many tribes.

The Calvin Coolidge Administration studied the effects of the Dawes Act and current conditions for Indians in what is known as the Meriam Report, completed in 1928. It found that the Dawes Act had been used illegally to deprive Native Americans of their land rights.

References

- ↑ Monday Evening Club website

- ↑ "Henry L. Dawes". New York Times. February 7, 1903. Retrieved 2012-09-18.

Ex-Senator Dawes had been for ten years out of public life when he died, and ten years is a long while for the memory of public service to last in so busy a land ...

- ↑ Merrill, Marlene Deahl, ed. (1999). Yellowstone and the Great West-Journals, Letters and Images from the 1871 Hayden Expedition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3148-2.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dawes, Henry Laurens". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 873.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dawes, Henry Laurens". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 873.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry L. Dawes. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Dawes, Henry Laurens. |

- United States Congress. "Henry L. Dawes (id: D000148)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-04-23

- "Dawes Act", Our Documents.gov website

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mark Trafton |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 11th congressional district 1857–1863 |

District eliminated |

| Preceded by Charles Delano |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 10th congressional district 1863–1873 |

Succeeded by Alvah Crocker |

| New district | Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 11th congressional district 1873–1875 |

Succeeded by Chester W. Chapin |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by William B. Washburn |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Massachusetts 1875–1893 Served alongside: George S. Boutwell and George F. Hoar |

Succeeded by Henry Cabot Lodge |