Chaim Herzog

| Chaim Herzog | |

|---|---|

|

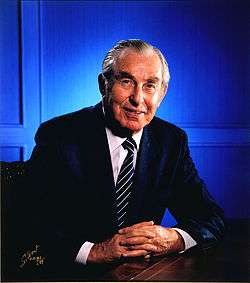

1989 portrait photo | |

| 6th President of Israel | |

|

In office 5 May 1983 – 13 May 1993 | |

| Prime Minister |

Menachem Begin Yitzhak Shamir Shimon Peres Yitzhak Shamir Yitzhak Rabin |

| Preceded by | Yitzhak Navon |

| Succeeded by | Ezer Weizman |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

17 September 1918 Belfast, Ireland |

| Died |

17 April 1997 (aged 78) Tel Aviv, Israel |

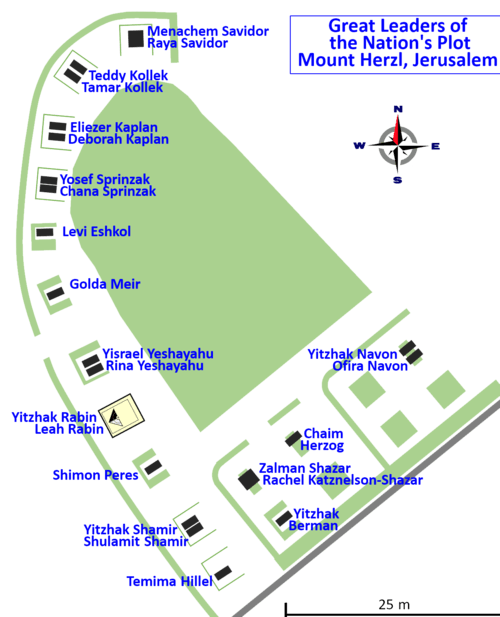

| Resting place | Mount Herzl, Jerusalem |

| Political party | Alignment (1981–91) |

| Spouse(s) |

Aura (née Ambache) (1947–97, his death) |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | "Vivian" |

| Allegiance |

United Kingdom (1943–47) Israel (1948–62) |

| Service/branch |

British Army Israel Defence Forces |

| Rank |

Major (UK) Major-General (Israel) |

| Battles/wars |

World War II 1948 Arab–Israeli War |

Major-General Chaim Herzog (Hebrew: חיים הרצוג; 17 September 1918 – 17 April 1997)[1] was an Israeli politician, general, lawyer and author who served as the sixth President of Israel between 1983 and 1993. Born in Belfast and raised predominantly in Dublin, the son of Ireland's Chief Rabbi Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, he emigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1935 and served in the Haganah Jewish paramilitary group during the 1936–39 Arab revolt. In the British Army during World War II, latterly as an officer, he received the nickname "Vivian" because the British could not pronounce "Chaim". He returned to Palestine after the war and, following the end of the British Mandate and Israel's Declaration of Independence in 1948, operated in the battles for Latrun during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. He retired from the Israel Defence Forces in 1962 with the rank of Major-General.

After leaving the military, Herzog practised law. In 1972 he was a co-founder of Herzog, Fox & Ne'eman, which would become one of Israel's largest law firms. Between 1975 and 1978 he served as Israel's Permanent Representative to the United Nations, in which capacity he repudiated UN General Assembly Resolution 3379—the "Zionism is Racism" resolution—and symbolically tore it up before the assembly. Herzog entered politics in the 1981 elections, winning a Knesset seat as a member of the Alignment. Two years later, in March 1983, he was elected to the largely ceremonial role of President. He served for two five-year terms before retiring in 1993. He died four years later and was buried on Mount Herzl, Jerusalem. His son Isaac Herzog has led the Israeli Labour Party and the parliamentary Opposition in the Knesset since 2013.[1]

Early life

Herzog was born on 17 September 1918 in Cliftonpark Avenue in Belfast, Ireland, the son of Rabbi Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, who was Chief Rabbi of Ireland from 1919 to 1937 (and, later, of Mandatory Palestine and the State of Israel), and his wife Sara (née Hillman).[2][3] His father was born in Łomża, Poland, and his mother in Latvia; his maternal grandfather was the Orthodox Jewish Talmudic scholar Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman. The family home from 1919 was at 33 Bloomfield Avenue, Portobello, Dublin.

Herzog's father, a fluent speaker of the Irish language, was known as "the Sinn Féin Rabbi" for his support of the First Dáil and the Irish Republican cause during the Irish War of Independence.[4] Herzog studied at Wesley College, Dublin and was involved with the Federation of Zionist Youth and Habonim Dror, the Labour-Zionist movement, during his teenage years.

The family emigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1935; Herzog subsequently served in the Jewish paramilitary group Haganah during the 1936–39 Arab revolt. He went on to earn a degree in law at University College London, and then qualified as a barrister at Lincoln's Inn.

Career

Herzog joined the British Army during World War II, operating primarily in Germany as a tank commander in the Armoured Corps.[2] There, he was given his lifelong nickname of "Vivian" because the British could not pronounce the name, "Chaim". A Jewish soldier had volunteered that "Vivian" was the English equivalent of "Chaim".[5] He was commissioned into the Intelligence Corps in 1943 and participated in the liberation of several Nazi concentration camps as well as identifying a captured German soldier as Heinrich Himmler. He left the army in 1947 with the rank of Major.

Military, legal and political career

Immediately following the war, he returned to Palestine. After the establishment of the State of Israel, he fought in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, serving as an officer in the battles for Latrun. His intelligence experience during World War II was seen as a valuable asset, and he subsequently became head of the IDF Military Intelligence Branch, a position in which he served from 1948 to 1950 and again from 1959 to 1962. From 1950 to 1954, he served as defence attaché at the Israeli Embassy in the United States. He retired from the IDF in 1962 with the rank of Major-General.

After leaving the army, Herzog opened a private law practice. He returned to public life in 1967, when the Six-Day War broke out, as a military commentator for Kol Israel radio news. Following the capture of the West Bank, he was appointed Military Governor of East Jerusalem, and Judea and Samaria.

In 1972, he went into partnership with Michael Fox and Yaakov Neeman, and established the law firm of Herzog, Fox & Neeman, one of the largest law firms in Israel.[6]

In 1975, Herzog was appointed Israel's Ambassador to the United Nations, in which capacity he served until 1978. During his term the UN adopted the "Zionism is Racism" resolution (General Assembly Resolution 3379), which Herzog condemned and symbolically tore up (as his father had done to one of the British white papers regarding the British Mandate in Palestine), saying: "For us, the Jewish people, this resolution based on hatred, falsehood and arrogance, is devoid of any moral or legal value. For us, the Jewish people, this is no more than a piece of paper and we shall treat it as such." In recent years British historians headed by Simon Sebag-Montefiore have included this speech in a book on speeches that changed the world, which includes others by Martin Luther King, Jr, Nelson Mandela, Winston Churchill and John F. Kennedy.[7][8]

In the 1981 elections, Herzog entered politics for the first time, winning a seat in the Knesset as a member of the Alignment, the predecessor to the Labour Party.

Presidency

On 22 March 1983, Herzog was elected by the Knesset to serve as the sixth President of Israel, by a vote of 61 to 57, against Menachem Elon, the candidate of the right and the government coalition. He assumed office on 5 May 1983 and served two five-year terms (then the maximum permitted by Israeli basic law), retiring from political life in 1993. As president of Israel, Herzog made a number of visits abroad, being the first Israeli president to make an official visit to Germany, as well as visiting several far-east countries, Australia, and New Zealand. He was also noted for pardoning the Shin Bet agent involved in the Kav 300 affair.

In 1985 during his state visit to Ireland, Herzog visited Wesley College Dublin, opened the Irish Jewish Museum in Dublin, and unveiled a modern polished steel Israeli sculpture, in honour of his childhood friend, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, former Chief Justice and later, the fifth President of Ireland, in Sneem Culture Park, County Kerry.

Herzog was a hardened opponent of Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq during his presidency of Israel, he referred to Iraq as a nest "of world terror". He said the world largely dismissed Israel's warnings that Baghdad was becoming a capital of world terrorism, adding that some Western countries helped Hussein develop into a military power.[9]

Herzog controversially reduced the sentences of three imprisoned Jews, Menachem Livni, Uzi Sharbaf and Shaul Nir, members of the Jewish Underground, who were sentenced to life imprisonment in 1985 for the 1984 murder of four Palestinians in the West Bank town of Hebron. Herzog had reduced the sentences, first to 24 years, then to 15 years, and in 1989, he reduced the sentence to 10 years, which enabled the men to be released two years later on good behavior.[10][11]

Commemorative plaque

In 1998, the Ulster History Circle unveiled a commemorative blue plaque to Herzog at his birthplace on Cliftonpark Avenue, Belfast. The plaque was removed by the Circle from the building in August 2014, at the request of the Cliftonville Community Regeneration Forum, who are based there. The plaque had become the subject of unwelcome attention, and in the interests of health and safety it was taken away for safe keeping, until such time as it can be reinstated, with the consent of the owners and occupiers of the premises.[12]

Personal life

Death

Herzog died on 17 April 1997. He is buried on Mount Herzl, Jerusalem.

Family

Herzog was the brother-in-law of Abba Eban; the men's wives were sisters. He had three children, including Isaac Herzog, a politician who is the chairman of the Israeli Labour Party.

Works and publications

- Herzog, Chaim (1978). Who Stands Accused?: Israel Answers Its Critics. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-50132-1. OCLC 3865344.

- Herzog, Chaim; Gazit, Shlomo (12 December 1983). The Arab-Israeli Wars: War and Peace in the Middle East from the 1948 War of Independence to the Present. Vintage. ISBN 978-1-4000-7963-6. OCLC 741355280.

- Herzog, Chaim (September 1989). Heroes of Israel: Profiles of Jewish Courage. Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-35901-6. OCLC 19510435.

- Herzog, Chaim (12 November 1996). Living History: A Memoir. Pantheon. ISBN 978-0-297-81941-7. OCLC 36792752.

- Herzog, Chaim; Gichon, Mordechai (March 1997). Battles of the Bible: A Military History of Ancient Israel. Pantheon. ISBN 978-0-7607-7626-1. OCLC 71323946.

- Herzog, Chaim (March 1998). The War of Atonement: The Inside Story of the Yom Kippur War. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-935149-13-2. OCLC 427612923.

References

- 1 2 Pace, Eric (18 April 1997). "Chaim Herzog, Former Israeli President, Dies at 78". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Herzog, Chaim (1918–1997)". Israel and Zionism. The Department for Jewish Zionist Education. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ↑ "Sara Herzog Dead at 82". JTA. 16 January 1979. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ Benson, Asher (2007). Jewish Dublin. Dublin: A&A Farmer Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-906353-00-1.

- ↑ Herzog, Living History, p. 47.

- ↑ Noam Sharvit (26 June 2006). "BDI: Herzog, Fox & Neeman remains top Israeli law firm". Globes. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Herzog speech on Zionism makes history". Ynetnews. 26 June 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ Colonel Tim Collins; York Membery (9 February 2011). "Ten of the greatest: Inspirational speeches". Daily Mail. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ Steve Padilla; Ronald L. Soble (19 November 1990). "Herzog Calls Iraq a Nest of Terrorism". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ "3 Israeli Terrorists Are Released In 4th Reduction of Their Terms". The New York Times. Associated Press. 27 December 1990. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ Alan Cowell (7 June 1989). "Documents given to Arabs in Gaza". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Chaim Herzog son saddened that Belfast plaque removed". BBC News. 13 August 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

External links

- Chaim Herzog on the Knesset website

- "Chaim Herzog". Jewish Virtual Library.

- "Chaim Herzog (1918–1997)". Jewish Agency for Israel.

- "Israel, Jewish world mourn death of Chaim Herzog, 78". j Weekly. JTA. April 25, 1997.

- Thomas L. Friedman (8 November 1987). "President of Israel to Make First Visit to U.S.". The New York Times.

- "Missles on Tel Aviv". Israel's Documented Story: The English-language blog of the Israel State Archives. 18 November 2012. Correspondence between President President Chaim Herzog and the German President Richard von Weizsaecker during the First Gulf War

- The End of World War II in Europe: Wartime Letters from Chaim Herzog to Family and Friends, published in Israel's Documented Story: The English-language blog of Israel State Archives:

- http://israelsdocuments.blogspot.co.il/2015/05/the-end-of-world-war-ii-in-europe.html