Heterotroph

A heterotroph (/ˈhɛtərəˌtroʊf, -ˌtrɒf/;[1] trophe = "nutrition") is an organism that cannot fix carbon from inorganic sources (such as carbon dioxide) but uses organic carbon for growth.[2][3] Heterotrophs can be further divided based on how they obtain energy; if the heterotroph uses light for energy, then it is considered a photoheterotroph, while if the heterotroph uses chemical energy, it is considered a chemoheterotroph.

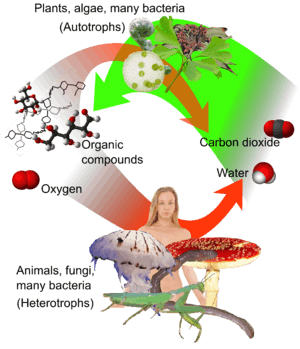

Heterotrophs contrast with autotrophs, such as plants and algae, which can use energy from sunlight (photoautotrophs) or inorganic compounds (lithoautotrophs) to produce organic compounds such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins from inorganic carbon dioxide. These reduced carbon compounds can be used as an energy source by the autotroph and provide the energy in food consumed by heterotrophs. Ninety-five percent or more of all types of living organisms are heterotrophic, including all animals and fungi and most bacteria and protists.[4]

Types

Organotrophs exploit reduced carbon compounds as energy sources, like carbohydrates, fats, and proteins from plants and animals. Photoorganoheterotrophs such as Rhodospirillaceae and purple non-sulfur bacteria synthesize organic compounds by utilization of sunlight coupled with oxidation of inorganic substances, including hydrogen sulfide, elemental sulfur, thiosulfate, and molecular hydrogen. They use organic compounds to build structures. They do not fix carbon dioxide and apparently do not have the Calvin cycle.[5] Chemolithoheterotrophs can be distinguished from mixotrophs (or facultative chemolithotroph), which can utilize either carbon dioxide or organic carbon as the carbon source.[6][7]

Heterotrophs, by consuming reduced carbon compounds, are able to use all the energy that they obtain from food for growth and reproduction, unlike autotrophs, which must use some of their energy for carbon fixation.[5] Both heterotrophs and autotrophs alike are usually dependent on the metabolic activities of other organisms for nutrients other than carbon, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, and can die from lack of food that supplies these nutrients.[8] This applies not only to animals and fungi but also to bacteria.[5]

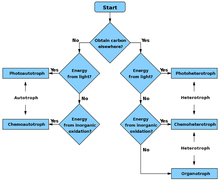

Flowchart

Ecology

Most heterotrophs are chemoorganoheterotrophs (or simply organotrophs) who utilize organic compounds both as a carbon source and an energy source. The term "heterotroph" very often refers to chemoorganoheterotrophs. Heterotrophs function as consumers in food chains: they obtain organic carbon by eating autotrophs or other heterotrophs. They break down complex organic compounds (e.g., carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) produced by autotrophs into simpler compounds (e.g., carbohydrates into glucose, fats into fatty acids and glycerol, and proteins into amino acids). They release energy by oxidizing carbon and hydrogen atoms present in carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins to carbon dioxide and water, respectively.

Most opisthokonts and prokaryotes are heterotrophic; in particular, all animals and fungi are heterotrophs.[4] Some animals, such as corals, form symbiotic relationships with autotrophs and obtain organic carbon in this way. Furthermore, some parasitic plants have also turned fully or partially heterotrophic, while carnivorous plants consume animals to augment their nitrogen supply while remaining autotrophic.

Animals are heterotrophs by ingestion, fungi are heterotrophs by absorption.

References

- ↑ Template:MerriamWebsterDictionaryang

- ↑ "heterotroph".

- ↑ Hogg, Stuart (2013). Essential Microbiology (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-119-97890-9.

- 1 2 "How Cells Harvest Energy". McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- 1 2 3 Mauseth, James D. (2008). Botany: an introduction to plant biology (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-7637-5345-0.

- ↑ Libes, Susan M. (2009). Introduction to marine biogeochemistry (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-12-088530-5.

- ↑ Dworkin, Martin (2006). The prokaryotes: ecophysiology and biochemistry (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 988. ISBN 978-0-387-25492-0.

- ↑ Campbell and Reece (2002). Biology (7th ed.). Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0805371710.