High-temperature electrolysis

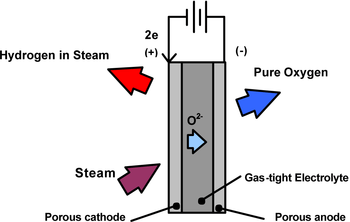

High-temperature electrolysis (also HTE or steam electrolysis) is a method being investigated for the production of hydrogen from water with oxygen as a by-product.

Efficiency

High temperature electrolysis is more efficient economically than traditional room-temperature electrolysis because some of the energy is supplied as heat, which is cheaper than electricity, and also because the electrolysis reaction is more efficient at higher temperatures. In fact, at 2500 °C, electrical input is unnecessary because water breaks down to hydrogen and oxygen through thermolysis. Such temperatures are impractical; proposed HTE systems operate between 100 °C and 850 °C.[1][2][3]

The efficiency improvement of high-temperature electrolysis is best appreciated by assuming that the electricity used comes from a heat engine, and then considering the amount of heat energy necessary to produce one kg hydrogen (141.86 megajoules), both in the HTE process itself and also in producing the electricity used. At 100 °C, 350 megajoules of thermal energy are required (41% efficient). At 850 °C, 225 megajoules are required (64% efficient).

Materials

The selection of the materials for the electrodes and electrolyte in a solid oxide electrolyser cell is essential. One option being investigated for the process[4] used yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) electrolytes, nickel-cermet steam/hydrogen electrodes, and mixed oxide of lanthanum, strontium and cobalt oxygen electrodes.

Economic potential

Even with HTE, electrolysis is a fairly inefficient way to store energy. Significant conversion losses of energy occur both in the electrolysis process, and in the conversion of the resulting hydrogen back into power.

At current hydrocarbon prices, HTE can not compete with pyrolysis of hydrocarbons as an economical source of hydrogen.

HTE is of interest as a more efficient route to the production of hydrogen, to be used as a carbon neutral fuel and general energy storage. It may become economical if cheap non-fossil fuel sources of heat (concentrating solar, nuclear, geothermal) can be used in conjunction with non-fossil fuel sources of electricity (such as solar, wind, ocean, nuclear).

Possible supplies of cheap high-temperature heat for HTE are all nonchemical, including nuclear reactors, concentrating solar thermal collectors, and geothermal sources. HTE has been demonstrated in a laboratory at 108 kilojoules (thermal) per gram of hydrogen produced,[5] but not at a commercial scale.[6] The first commercial generation IV reactors are expected around 2030.

The market for hydrogen production

Given a cheap, high-temperature heat source, other hydrogen production methods are possible. In particular, see the thermochemical sulfur-iodine cycle. Thermochemical production might reach higher efficiencies than HTE because no heat engine is required. However, large-scale thermochemical production will require significant advances in materials that can withstand high-temperature, high-pressure, highly corrosive environments.

The market for hydrogen is large (50 million metric tons/year in 2004, worth about $135 billion/year) and growing at about 10% per year (see hydrogen economy). This market is met by pyrolysis of hydrocarbons to produce the hydrogen, which results in CO2 emissions. The two major consumers are oil refineries and fertilizer plants (each consumes about half of all production). Should hydrogen-powered cars become widespread, their consumption would greatly increase the demand for hydrogen in a hydrogen economy.

Electrolysis and thermodynamics

During electrolysis, the amount of electrical energy that must be added equals the change in Gibbs free energy of the reaction plus the losses in the system. The losses can (theoretically) be arbitrarily close to zero, so the maximum thermodynamic efficiency of any electrochemical process equals 100%. In practice, the efficiency is given by electrical work achieved divided by the Gibbs free energy change of the reaction.

In most cases, such as room temperature water electrolysis, the electric input is larger than the enthalpy change of the reaction, so some energy is released as waste heat. In the case of electrolysis of steam into hydrogen and oxygen at high temperature, the opposite is true. Heat is absorbed from the surroundings, and the heating value of the produced hydrogen is higher than the electric input. In this case the efficiency relative to electric energy input can be said to be greater than 100%. The maximum theoretical efficiency of a fuel cell is the inverse of that of electrolysis. It is thus impossible to create a perpetual motion machine by combining the two processes.

Mars ISRU

High temperature electrolysis with solid oxide electrolyser cells has also been proposed to produce oxygen on Mars from atmospheric carbon dioxide, using zirconia electrolysis devices.[7][8]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Badwal, SPS; Giddey S; Munnings C (2012). "Hydrogen production via solid electrolytic routes". WIRES; Energy and Environment. 2 (5): 473–487. doi:10.1002/wene.50.

- ↑ Hi2h2 - High temperature electrolysis using SOEC

- ↑ WELTEMP-Water electrolysis at elevated temperatures

- ↑ Kazuya Yamada, Shinichi Makino, Kiyoshi Ono, Kentaro Matsunaga, Masato Yoshino, Takashi Ogawa, Shigeo Kasai, Seiji Fujiwara, and Hiroyuki Yamauchi "High Temperature Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production Using Solid Oxide Electrolyte Tubular Cells Assembly Unit", presented at AICHE Annual Meeting, San Francisco, California, November 2006. abstract

- ↑ "Steam heat: researchers gear up for full-scale hydrogen plant" (Press release). Science Daily. 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Nuclear hydrogen R&D plan" (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Energy. March 2004. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (August 1, 2014). "Oxygen-Generating Mars Rover to Bring Colonization Closer". Space.com. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- ↑ The Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment (MOXIE) PDF. Presentation: MARS 2020 Mission and Instruments". November 6, 2014.