Hirosaki Domain

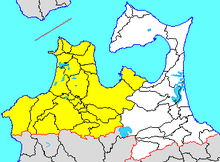

Hirosaki Domain (弘前藩 Hirosaki-han), also known as Tsugaru Domain (津軽藩 Tsugaru-han), was a Japanese domain of the Edo period.[1] It was located in northern Mutsu Province (modern-day Aomori Prefecture), Japan. It was centered on Hirosaki Castle in what is now the city of Hirosaki, Aomori. It was ruled by the Tsugaru clan. A branch of the family ruled the adjoining Kuroishi Domain.

History

Foundation

The Tsugaru clan, originally the Ōura clan (大浦氏 Ōura-shi), was originally a subordinate branch of the Nambu clan, holding portions of northern Mutsu Province. Ōura Tamenobu revolted against his overlord, and receiving the support of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was confirmed as an independent warlord in 1590 and changed his name to “Tsugaru”. Tamenobu assisted Hideyoshi at the Battle of Odawara, and accompanied his retinue to Hizen during the Korean Expedition. Afterwards, he sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu during the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.[2]

History

After the Tokugawa victory at Sekigahara, the Tsugaru clan was granted an increase in territory, along with permission to keep its existing domain of Hirosaki (named for the family's castle town). [3] Tamenobu remained politically active in the early years of the Edo era, mainly in the Kansai area; he died in Kyoto in 1608.[4]

Tamenobu was followed by his son, Tsugaru Nobuhira (ruled 1607-1631), who had been baptized as a Kirishitan. His inheritance was initially challenged by faction which supported his nephew in the Tsugaru Disturbance (津軽騒動 Tsugaru-sōdō) of 1607. Nobuhira initially gave shelter to many Kirishitan persecuted in 1614, but later recanted his faith. He completed Hirosaki Castle, and developed the port of Aomori on Mutsu Bay. Nobuhira was followed by his son, Tsugaru Nobuyoshi (ruled 1631–1655), whose period was marked by a series of major O-Ie Sōdō disturbances that shook the Tsugaru family: Kōsaka Kurando's Riot (高坂蔵人の乱 Kōsaka Kurando no ran) of 1612, the Funabashi Disturbance (船橋騒動 Funabashi-sōdō) of 1634, and the Shōhō Disturbance (正保騒動 Shōhō-sōdō) of 1647.

Tsugaru Nobumasa (ruled 1656-1710) was a scholar, and embarked on ambitious public works projects aimed at increasing the revenues of the domain; however, in 1695, crop failure resulted in widespread famine and starvation in the area.

His son, Tsugaru Nobuhisa (ruled 1710-1731) was also a noted scholar, and attempted to continue his father’s public works projects, but was plagued by repeated eruptions of Mount Iwaki. Ignoring sumptuary laws imposed by the shogunate, he lived in luxury while his subjects and retainers fell deeper into poverty. He continued to rule behind-the-scenes during the time of his son, Nobuaki (ruled 1731-1744), during which time the castle town of Hirosaki burned down. His grandson, Nobuyasu (ruled 1744-1784) and great-grandson Nobuakira (ruled 1784-1791), inherited a domain deeply in debt, beset by corrupt retainers, constant eruptions by Mount Iwaki, crop failures and famine.

As Nobuakira died without heir, the domain was inherited by Tsugaru Yasuchika, from a hatamoto branch of the Tsugaru clan was founded in 1656 residing in Kuroishi. He promoted the branch house to daimyo status in 1809,[5] He implemented many reforms which restored some stability to the domain, but orders from the Tokugawa Shogunate to assist in policing the frontier region of Ezo (now Hokkaido) placed a severe strain on the domain.[6] In 1821, he survived an assassination attempt by Sōma Daisaku, a former retainer of the Nanbu clan, stemming from the old enmity between the two clans. Yasuchika continued to rule behind-the-scenes during the time of his son, Nobuyuki (ruled 1825-1839), who was noted for his mismanagement.

Nobuyuki was followed by Tsugaru Yukitsugu (ruled 1839-1859), who was born as the 5th son of Matsudaira Nobuakira, daimyō of Yoshida Domain in Mikawa Province. He was adopted in 1821 as the heir to Tsugaru Chikatari, the 8th Lord Kuroishi, and 1st daimyō of Kuroishi Domain. On his adoptive father’s retirement, as Tsugaru Yukinori, he became the 2nd daimyō of Kuroishi Domain from 1825 to 1839. After the Tokugawa bakufu forced Nobuyuki into retirement over allegations of gross misrule, Yukinori was ordered to change his name to Tsugaru Yukisugu and to take his place as the 11th daimyō of Hirosaki. He attempted to continue implementation many of the reforms initiated by Nobuakira to restore prosperity to the disaster-prone domain, expanding on Nobuakira’s code of ethics from five articles to thirty in an attempt to control his unruly retainers. In addition to opening new paddy fields, Tsuguyasu established a foundry for the casting of cannons, and attempted to modernize the domain’s military and medical level through the introduction of rangaku studies.

Yukitsugu’s son Tsuguakira became the last daimyō of Tsugaru Domain during the turbulent Bakumatsu period, during which time the Tsugaru clan [7] first sided with the pro-imperial forces of Satchō Alliance, and attacked nearby Shōnai Domain.[8][9] However, the Tsugaru soon switched course, and briefly joined the Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei.[10] However, for reasons yet unclear, the Tsugaru backed out of the alliance and re-joined the imperial cause after a few months, participating in several battles in the Imperial cause during the Boshin War, notably that of the Battle of Noheji, and Battle of Hakodate.[8]

After the Meiji Restoration, with the abolition of the han system, Yukitsugu was appointed Imperial Governor of Hirosaki from 1869 to 1871, at which time the territory was absorbed into the new Aomori Prefecture.

The main Tsugaru family's funerary temple in Hirosaki was located at Chōshō-ji in Hirosaki,[11] as well as the temple of Juyo-in in Taitō-ku, Tokyo.

List of daimyō

-

Tsugaru clan (tozama) 1590-1865

Tsugaru clan (tozama) 1590-1865

| # | Name | Tenure | Courtesy title | Court Rank | revenues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tsugaru Tamenobu (津軽 為信) | 1590–1607 | Saikyo Daiyu | Lower 4th (従四位下) | 47,000 koku |

| 2 | Tsugaru Nobuhira (津軽信枚) | 1607–1631 | Etchu-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 3 | Tsugaru Nobuyoshi (津軽信義) | 1631–1655 | Tosa-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 4 | Tsugaru Nobumasa (津軽信政) | 1656–1710 | Etchu-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 5 | Tsugaru Nobuhisa (津軽信寿) | 1710–1731 | Tosa-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 6 | Tsugaru Nobuaki (津軽信著) | 1731–1744 | Dewa-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 7 | Tsugaru Nobuyasu (津軽信寧) | 1744–1784 | Etchu-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 8 | Tsugaru Nobuakira (津軽信明) | 1784–1791 | Tosa-no-kami | Lower 5th (従五位下) | 50,000 koku |

| 8 | Tsugaru Yasuchika (津軽寧親) | 1791–1825 | Saikyo-daiyu | Lower 4th (従四位下) | 117,000 koku |

| 9 | Tsugaru Nobuyuki (津軽信順) | 1825–1839 | Jiju | Lower 4th (従四位下) | 217,000 koku |

| 10 | Tsugaru Yukitsugu (津軽順承) | 1839–1859 | Sakonenoshogen | Lower 4th (従四位下) | 217,000 koku |

| 11 | Tsugaru Tsuguakira (津軽承昭) | 1859–1871 | Tosa-no-kami | Lower 4th (従四位下) | 217,000 koku |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ravina, Mark. (1998). Land and Lordship in Early Modern Japan, p. 222.

- ↑ Edwin McClellan (1985). Woman in the Crested Kimono (New Haven: Yale University Press), p. 164.

- ↑ (Japanese) "Tsugaru-han" on Edo 300 HTML.

- ↑ (Japanese) Tsugaru-shi on Harimaya.com.

- ↑ Onodera Eikō (2005). Boshin nanboku sensō to Tōhoku seiken. (Sendai: Kita no mori), p. 134.

- ↑ Noguchi Shin'ichi (2005). Aizu-han. (Tokyo: Gendai shokan), p. 194.

- ↑ Koyasu Nobushige (1880), Buke kazoku meiyoden vol. 1 (Tokyo: Koyasu Nobushige), p. 25. (Accessed from National Diet Library, 17 July 2008)

- 1 2 McClellan, p. 175.

- ↑ Ravina, pp. 152-153.

- ↑ Onodera, p. 140.

- ↑ Jan Dodd (2001), The rough guide to Japan. (n.p.: Rough Guides), p. 288.

References

- McClellan, Edwin (1985). Woman in the Crested Kimono. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sasaki Suguru (2002). Boshin sensō: haisha no Meiji ishin. Tokyo: Chūōkōron-shinsha.

- Papinot, E (1910). Historical and Geographic Dictionary of Japan. Tuttle (reprint) 1972.

- (Japanese) Tsugaru on "Edo 300 HTML"

Further reading

In Japanese

- Kurotaki, Jūjirō (1984). Tsugaru-han no hanzai to keibatsu 津軽藩の犯罪と刑罰. Hirosaki: Hoppō shinsha.

In English

- Dazai, Osamu (1985). Return to Tsugaru: travels of a purple tramp. Tokyo: Kodansha International.