History of Galway

Galway, one of the largest cities in Ireland, situated on the west coast of Ireland, has a complex history going back around 800 years. The city was the only medieval city in the province of Connacht.

(Alternative) derivations of the name

The city takes its name from that of the river,[1] the Gaillimh. The word Gaillimh means "stony" as in "stony river" . Today, the river is commonly called the River Corrib, after Lough Corrib, just to the north. In Irish, Galway is also called Cathair na Gaillimhe ("city of Galway") which is a modern creation to prevent confusion with Contae na Gaillimhe / County Galway which is often incorrectly called Gaillimh in Irish.

There are multiple alternative derivations of the name, some conjectural and some mythical:

- The commonly held view that the city takes its name from the Irish word Gallaibh, "foreigners" i.e. "the town of the foreigners" (from Gall, a foreigner) is incorrect, since the name Gaillimh was applied to the river first and then later on to the town. Also the common word gallaibh (which is pronounced with a broad initial letter a has never been used as an alternative spelling of Gaillimh (which is pronounced without a broad initial letter a.))

- The daughter of a local chieftain drowned in the river, and her name was Gailleamh, thus the river was given her name. The chieftain was so distraught that he set up camp at the point to mourn her spirit and keep it company. Later, a town sprung up around the point, and was called Gaillimh in her honour.

Early Galway

Dún Bhun na Gaillimhe ('Fort at the Mouth of the Gaillimh') was constructed in 1124, by the King of Connacht Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. The Annals of the Four Masters note that in that year "Three castles were erected by the Connaughtmen, the castle of Dun-Leodhar, the castle of the Gaillimh, and the castle of Cuil-maeile." This fort is also called a caislean (castle) in the annals. It was attacked in 1132 and 1149. Galway lay in the túath of Clann Fhergail which covered the parishes of St. Nicholas (the medieval city), Roscam and part of Baile an Chláir / Claregalway parish. This district was held by the Ó hAllmhuráin/O'Halloran clan. Clann Fhergail itself was a sub district of Uí Bhriúin Seola the territory of which is called Maigh Seola ('plain of Seola'). The Ó Flaithbheartaigh clan held it up until the Norman invasion of Connacht in the 1230s. As Dún Bhun na Gaillimhe lay in the territory of the O Flahertys they are often recorded as holding this fort for the O Connor Kings of Connacht.

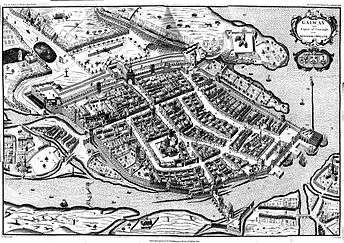

Following an unsuccessful week-long siege in 1230, Dún Bhun na Gaillimhe was captured by Richard Mor de Burgh in 1232. Over the following century Galway thrived under the de Burghs (Burkes), becoming a small walled town. After the sundering of the de Burgh (Clanrickards) dynasty in 1333, Galway sought its independence from the feuding Clanrickard Burkes, receiving a murage charter (authority to build a defensive wall) from the Crown in 1396. The English-oriented merchant families – known from the 1600s as The Tribes of Galway – were anxious to have control over their own affairs without the interference of the Gaelicised Burkes. With independence from the Burkes achieved, Galway became to a large degree culturally and politically aloof (but not isolated) from the surrounding Gaelic and Gaelic-Norman territories.

Medieval City

Galway received a municipal charter from the crown in December 1484. This ensured the town's independence from the Clanrickard Burkes. At the same time, the creation of the wardenship of Galway gave the townsmen control of the large parish church, St. Nicholas' Collegiate Church.

Galway endured difficult relations with its Irish neighbours. A notice over the west gate of the city, completed in 1562 by Mayor Thomas Óge Martyn, stated "From the Ferocious O'Flahertys may God protect us". A bye-law forbade the native Irish (as opposed to Galway's Old English citizens) unrestricted access into Galway, saying "neither O' nor Mac shall strutte nor swagger through the streets of Galway" without permission.

During the Middle Ages, Galway was ruled by an oligarchy of fourteen1 merchant families (12 of Anglo-Norman origin and 2 of Irish origin), the 'Tribes of Galway. The city thrived on international trade. In the Middle Ages, it was the principal Irish port for trade with Spain and France, being the main source of trade to the Western Isles, Scotland, during the Lordship of the Isles. In 1477 Christopher Columbus visited Galway, possibly stopping off on a voyage to Iceland or the Faroe Islands. Seven or eight years later, he noted in the margin of his copy of Imago Mundi "Men of Cathay have come from the west. [Of this] we have seen many signs. And especially in Galway in Ireland, a man and a woman, of extraordinary appearance, have come to land on two tree trunks [or timbers? or a boat made of such?]" The most likely explanation for these bodies is that they were Inuit swept eastward by the North Atlantic Current[1]

The population of medieval Galway is thought to have been about 3000.

Decline

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Galway was in a delicate position, caught, in effect between the Catholic rebels (Confederates) and its English garrison ensconced in Fort Hill just outside the city. Eventually, Galway citizens, who were predominantly Catholic, went against their garrison and supported the confederate side in 1642. The fort was besieged with the aid of Confederate troops until it surrendered and its garrison was evacuated by sea. During the 1640s, Galway was heavily fortified against an expected counter-attack by English forces, which eventually materialised when English Parliamentarian forces re-conquered Ireland in 1649–52. Galway surrendered to Cromwellian forces in 1652 after a nine-month siege; plague and expulsions of Catholic citizens followed. The Cromwellian Act of Settlement 1652 caused major upheavals, as peoples from east of the Shannon were transplanted to Connacht and slipped back.

After the demise of the English Commonwealth and the English Restoration in 1660, (and the further Act of Settlement 1662 and its Act of Explanation 1665), the economy of Galway recovered somewhat. In the next crisis, centred on the deposition of the Catholic King James II, in 1689, Galway supported the Jacobite side. It surrendered without a siege under the Articles of Galway of 1691 after the annihilation of the main Jacobite army at the nearby battle of Aughrim. Thereafter, the city became an economic backwater, and the capital of its old great families were spent overseas. It took about 300 years for the city to regain its former status.

18th century

After the 17th century wars, Galway, as a Catholic port city, was treated with great suspicion by the authorities. Legislation of 1704 (the Popery Act) stated that no new Catholics apart from seamen and day labourers could move there. On top of that, when fears arose of a French invasion of Ireland in 1708 and 1715 (during the Jacobite rising of 1715 in Scotland), all Catholics were ordered to leave the city. The corporation, which ran Galway was also confined to Protestants. This is all the more surprising given that a 1762 census showed that of the town's 15,000 or so inhabitants, only 350 were Protestants. The persecution of Galway's old Catholic merchant elite meant that trade declined substantially, and the once busy harbour fell into disrepair. Local traders compensated to some degree for this by smuggling in goods like brandy through gaps in the town walls. On 1 November 1755 the 1755 Lisbon earthquake caused a two-metre tsunami to hit the city's coast, causing some serious damage to the "Spanish Arch" section of the city wall.

19th century

Galway's economy recovered somewhat from the late 18th as the Penal Laws were relaxed. However the city's rural hinterland suffered terribly in the Great Irish Famine on the 1840s. Unlike other urban centres in 19th century Ireland, which experienced an explosion in their populations, Galway's population actually declined such was the devastation wrought by the famine.

The second half of the century saw some improvement in Galway's position however, as the railway lines reached the city in 1850. Another important development was the creation of a university in Galway in 1845, then named "Queens University of Ireland".

20th century

Galway city played a relatively minor role in the upheaval in Ireland from 1916–1923. In 1916, during the Easter Rising, Liam Mellows mobilised the local Irish Volunteers in the area to attack the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks at Oranmore, just outside Galway, however they failed to take it and later surrendered in Athenry. During the Irish War of Independence 1919–21, Galway was the western headquarters for the British Army. Their overwhelming force in the city meant that the local Irish Republican Army could do little against them. The only initiatives were taken by the University battalion of the IRA, who were reprimanded by the local IRA commander who was afraid they would provoke reprisals. This fear was not without justification, as the nearby town of Tuam was sacked on two occasions by the Black and Tans in July and September 1920. In November 1920, a Galway city Catholic priest, Fr. Michael Griffin was abducted and shot by the British forces. His body was found in a bog in Barna. Galway businessmen launched a boycott against Northern Irish goods from December 1919 onwards in protest against the loyalist attacks on Catholic nationalists in Belfast, a protest that later spread throughout the country.

Before the outbreak of the Irish Civil War (1922–23), in March 1922, Galway saw a tense stand off between Pro-Treaty and Anti-Treaty troops over who would occupy the military barracks at Renmore. After fighting broke out in July 1922 the city and its military barracks were occupied by troops of the Irish Free State's National Army. Two Free State soldiers and one Anti-Treaty fighter were killed and more wounded before the National Army secured the area. The Republicans burned a number of public buildings in the centre of town before they abandoned Galway.

In 1972, part of the city center was destroyed by fire. The area involved the southern-west corner of Eyre Square, where the Bank of Ireland used to be situated.

In more recent years, the resignation of Eamon Casey as Bishop of Galway in "scandalous circumstances" in 1992 came to be seen as pivotal in the Roman Catholic Church's loss of influence in Ireland.

Annalistic references

- 927. The foreigners of Luimneach went upon Loch Oirbsen, and the islands of the lake were plundered by them.[2]

- 928. A slaughter was made of the foreigners who were on Loch Oirbsen by the Connaughtmen.[3]

- 932. Fire from heaven burned the mountains of Connaught this year, and the lakes and streams dried up; and many persons were also burned by it.[4]

- 1124. Three castles were erected by the Connaughtmen, the castle of Dun-Leodhar, the castle of the Gaillimh, and the castle of Cuil-maeile.[5]

- 1125. The two sons of Aineislis Ua hEidhin were slain in treachery at Bun-Gaillimhe/Flann and Gillariabhach, the two sons of Aineislis Ua hEidhin, were slain by Conchobhar Ua Flaithbheartaigh.[6]

- 1132 The castle of Bun-Gaillmhe was burned and demolished by a fleet of the men of Munster; and a great slaughter was made of the people of West Connaught, together with Ua Taidhg an Teaghlaigh, and many other noblemen.[7]

- 1132. A hosting on land by Cormac Mac Carthaigh and the nobles of Leath Mogha into ... and Uí Eachach and Corca Laoighdhe, and the fleet of Leath Mogha [came] by sea to meet them, and they demolished the castle of Bun Gaillmhe, and plundered and burned the town. The defeat of An Cloidhe [was inflicted] on the following day on [the men of] Iarthar Connacht by the same fleet, and Conchobhar Ua Flaithbheartaigh, king of Iarthar Connacht, was killed, with slaughter of his people ... together with Ua Taidhg an Teaghlaigh, and many other noblemen.[8]

- 1178. The River Galliv was dried up for a period of a natural day; all the articles that had been lost in it from remotest times, as well as its fish, were collected by the inhabitants of the fortress, and by the people of the country in general.[9]

- 1577. Alexander, son of Calvagh, son of Turlough, son of John Carragh Mac Donnell, was slain in a combat by Theobald Boy Mac Seoinin, in the gateway of Galway; and there were not many sons of gallowglasses in Ireland at that time who were more wealthy, or who were more bountiful and munificent than he.[10]

- 1581. The son of the Earl of Clanrickard, i.e. William Burke, son of Rickard Saxonagh, son of Ulick-na-gCeann, son of Rickard, son of Ulick of Cnoc-Tuagh, was hanged at Galway, the third day after the execution of Turlough O'Brien; that is, Turlough was hanged on Thursday, and William on Saturday. It happened that William was joined with his relatives in the war when they demolished their castles, as we have already mentioned; that he grew sorry for this, and went to Galway, under the protection of the English, the month before his execution; but some tale was fabricated against him, for which he was taken and hanged. Such of his followers as went in under this protection were also hanged.[11]

- 1586. A session was held at Galway in the month of December of this year, and many women and men were put to death at it; and Edmond Oge, the son of Edmond, son of Manus Mac Sheehy, and eight soldiers of the Geraldines along with him, were put to death, information having been given against them that they had been along with those Scots who were slain at Ardnarea.[12]

Further reading

James Hardiman's History of Galway is considered to the definitive history of Galway city and county from the earliest of times until the early 19th century.

The book is now out of copyright and is available online.[13]

A more recent book by John Cunningham, dealing with Galway's 19th-century history was published during 2004. It is entitled 'A town tormented by the sea: GALWAY, 1790–1914', and several excerpts from it are available online.[14]

See J.G Simms's War and Politics in Ireland 1649–1731 for details of 18th century Galway.

References

- 1 2 David B. Quinn "Columbus and the North: England, Iceland, and Ireland", The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol 49, No. 2 (Apr. 1992), pp. 278–297

- ↑ Annals of the four masters M927.13 from Annal M923

- ↑ Annals of the four masters M928.10 from Annal M923

- ↑ Annals of the four masters M932.6 from Annal M923

- ↑ Annals of the four masters M1124.15 from Annal M1123

- ↑ Annals of the four masters M1125.8 from Annal M1123

- ↑ Annals of the four masters M1132.9 from Annal M1123

- ↑ Part 2 of MacCartaigh's Book MCB1132.1 from Annal MCB1132

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters M11378.9 from Annal M1178

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters M1577.10 from Annal M1577

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters M1581.2 from Annal M1581

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters M1586.1 from Annal M1586

- ↑ Galway.net

- ↑ John-cunningham.com

Notes

^1 The recent tendency to shorten town and city names in Irish has led to some confusion. The name of the city, Cathair na Gaillimhe, has been shortened to Gaillimh, which in turn has led to people misnaming the river Abhainn na Gaillimhe. Literally, this means "the river of the stony river", a nonsense.