History of Vilnius

| "Legend has it that the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Gediminas, was hunting in the sacred forest near the Valley of Šventaragis. Tired after the successful day's hunt, the Grand Duke settled in nearby for the night. He fell soundly asleep and began to dream. A huge Iron Wolf was standing on top a hill and the sound of hundreds of other wolves inside it filled all of the surrounding fields and woods. Upon awakening, the Duke asked the pagan priest Lizdeika to interpret the meaning of the dream. And the priest told him: "What is destined for the ruler and the State of Lithuania, is thus: the Iron Wolf represents a castle and a city which will be established by you on this site. This city will be the capital of the Lithuanian lands and the dwelling of their rulers, and the glory of their deeds shall echo throughout the world" |

| The Legend of the Founding of Vilnius[1] |

This article is about the history of Vilnius, the capital and largest city of Lithuania.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The earliest settlements in the area of present-day Vilnius appear to be of mesolithic origin. Numerous archaeological findings in different parts of the city prove that the area has been inhabited by peoples of various cultures since the early Middle Ages. Initially a Baltic settlement, later it was also inhabited by Slavs, Jews and Germans. Some historians identify the city with Voruta, a forgotten capital of King Mindaugas.

The city was first mentioned in written sources as Vilna in 1323 as the capital city of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the letters of Gediminas. Gediminas built his wooden castle on a hill in the city. The city became more widely known after he wrote a circular letter of invitation to Germans and Jews to the principal Hansa towns in 1325, offering free access into his domains to men of every order and profession. Vilnius was granted city rights by Jogaila in 1387, following the Christianization of Lithuania and the construction of the Vilnius Cathedral. The town was initially populated by local Lithuanians, but soon the population began to grow as craftsmen and merchants of other nationalities settled in the city.

According to a tale, tired after a busy hunting day, Gediminas had a prophetic dream about an iron wolf howling on a top of the hill. When he asked a krivis (a pagan priest) Lizdeika for an explanation of the dream, he was told that he must build a castle on the top of that hill, which is strategically surrounded by three rivers (Neris, Vilnia, and Vingria (now underground)) and a grand city around that hill, so that "the iron-wolf-like sound about this great city would spread around the world". Some versions of this tale state, that for his advice, Lizdeika was given a name of Radziwiłł.[4][5][5][6] The derivative of a Lithuanian name Radvila has also been interpreted as derived from the Belarusian word "радзіць" or Polish "radzi" (meaning "advises"). (The Lithuanian word for "wolf" is vilkas.)

English king Henry IV spent a full year of 1390 supporting the unsuccessful siege of Vilnius by Teutonic Knights with his 300 fellow knights. During this campaign Henry Bolingbroke also bought captured Lithuanian princes and then apparently took them back to England. King Henry's second expedition to Lithuania in 1392 illustrates the financial benefits to the Order of these guest crusaders. His small army consisted of over 100 men, including longbow archers and six minstrels, at a total cost to the Lancastrian purse of £4,360. Much of this sum benefited the local economy through the purchase of silverware and the hiring of boats and equipment. Despite the efforts of Bolingbroke and his English crusaders, two years of attacks on Vilnius proved fruitless.

Between 1503 and 1522, for the sake of protection from Crimean Tatar attacks, the city was surrounded by defensive walls that had nine gates and three towers. Communities of Lithuanians, Jews, Ruthenians, and Germans were present in different areas of Vilnius. The Orthodox inhabitants concentrated in the eastern part of the city left of the "Castle Street", while mostly Germans and Jews occupied the western side of the city around the "German Street". The town reached the peak of its development under the reign of Sigismund II Augustus, Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, who relocated there in 1544. In the 16th century Vilnius became a constantly growing and developing city, as Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland Sigismund II Augustus and his mother queen Bona Sforza were spending much of their time in the Royal Palace of Lithuania.

The Polonization of Vilnius proceeded through the influx of Polish elements and assimilation of non-Polish burghers. It started in the late 14th century with the arrival of Polish clergy, followed by artisans and merchants; they migrated in larger numbers after the Polish court of Sigismund August moved to the city.[7]

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

.jpg)

After the Union of Lublin (1569) that created the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the city flourished further in part due to the establishment of Vilnius University by Stephen Báthory, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1579. The university soon developed into one of the most important scientific and cultural centers of the region and the most notable scientific center of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Political, economic and social life was in full swing there. This is among all proven by the Lithuanian Statutes issued in the 16th century, the last of which was still in force until the 19th century. In 1610 the city was racked by a large fire.[8] In 1769 the Rasos Cemetery was founded; today it is one of the oldest surviving cemeteries in the city.

Rapidly developing, the city was open to migrants from both East and West. In addition to old citizens, larger Jewish, Orthodox and German communities established themselves in the city. Each group made its contribution to the life of the city, and crafts, trade and science prospered. In the 17th century, Polish and polonized elements achieved a cultural and likely numerical preponderance.[7] In 1655 during the Russo-Polish War (1654–67) Vilnius was captured by the forces of Tsardom of Russia and was pillaged, burned and the population was massacred. The death toll of around 20,000 included a large proportion of Vilnius Jews.[9] The city's growth lost its momentum for many years, yet the number of inhabitants recovered. During the decline of the Commonwealth, Vilnius became known as "Jerusalem of the North" - a major religio-cultural center of Eastern European Jewry.[10]

Russian Empire

After the Third Partition of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, Vilnius was annexed by the Russian Empire and became the capital of Vilna Governorate, a part of the Northwestern Krai. In order to allow the city to expand, between 1799–1805 period, the city walls were pulled down, only the Dawn Gate (also known as Aušros vartai, Medininkų vartai or Ostra Brama, Вострая Брама) remained. In 1803 Alexander I re-established the Polish-language University.[11] In 1812 the city was seized by Napoleon on his push towards Moscow. After the failure of the campaign, the Grande Armée retreated to the area where 80,000 of French soldiers died and were buried in the trenches they had built months earlier. After the November Uprising the Vilnius University was closed and repressions halted the further development of the city. Civil unrest in 1861 was suppressed by the Imperial Russian Army.[12] During the January Uprising in 1863 heavy city fights occurred, but were brutally pacified by Mikhail Muravyov, nicknamed The Hanger by the population because of the number of executions he organized. After the uprising, Polish language was banned from public use. The Latin alphabet was prohibited in 1859 (Belarusian language) and in 1865 (Lithuanian language) - the ban was lifted in 1904.[13]

During the second half of 19th and the beginning of 20th century Vilnius also became one of the centers of Jewish, Polish, Lithuanian and Belarusian national rebirths. According to the 1897 Russian census, by mother tongue, 40% of the population was Jewish, 31% Polish, 20% Russian, 4.2% Belarusian and 2.1% Lithuanian.[14][15] Jewish culture and population was so dominant that some Jewish national revival leaders argued for a new Jewish state to be founded in a Vilnius region, with a city as its capital. These national revivals happened in Vilnius because it was one of the most tolerant, progressive and liberal places in a region, legacy of the tolerance deriving from the years of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. One of the most important Polish, Belarusian poets and writers published their works in Vilnius at that time. It was the place where the first short-lived Belarusian weekly Naša Niva was founded.

Vilnius became an important place of act of the Lithuanian national revival on December 4–5, 1905, when the Great Seimas of Vilnius was held in the Palace of the present-day National Philharmonics, with over 2000 delegates from all regions of Lithuania as well as emigrees. It was decided to make a demand to establish an autonomous ethnic Lithuanian state within the Russian Empire with its parliament (Seimas) in Vilnius.

Interwar period

Polish-Lithuanian conflict

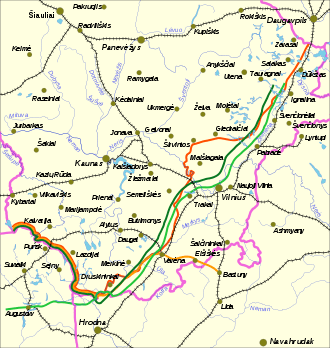

During World War I, Vilnius was occupied by Germany from 1915 until 1918. Still under German occupation, Council of Lithuania proclaimed the Act of Independence of Lithuania in Vilnius on February 16, 1918. Act proclaimed restoration of the independent state of Lithuania with Vilnius as its capital. The German civilian administration of the Ober-Ost declined to pass full authority to Lithuania, which was not controlled by the Germans any more. Instead, the Germans tried to control the area by means of promoting conflicts between local nationalities as it became clear that the German plan for creation of Mitteleuropa, a net of satellite buffer states, failed.

Finally, on January 1, 1919, the German garrison withdrew and passed the authority over the city to a local Polish committee, against the pleas of the Lithuanian administration. A Polish administration started to be formed.[16] Former members of the local Polish Self-Defence formations, now formally enlisted into the Polish Army, took over the posts while the Lithuanians withdrew along with the Germans.[17] On January 5, 1919 the city was taken by Bolshevik forces[16][18] advancing from the east. Vilnius was proclaimed the capital of the Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.[19] For the next 4 months the city became a communist experiment in governance.[20] During the course of that conflict, on April 19, 1919 the city was again seized by Poland (Vilna offensive), this time by forces of the regular Polish Army.[20] A year later, on July 14, 1920 it was lost to Soviet forces again (this time, the Soviets were aided by Lithuanians, who were promised Vilnius).[21]

Shortly after the defeat in the Battle of Warsaw in 1920, the withdrawing Red Army handed the city over to Lithuania, in accordance with the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty of July 12 of that year.[22] The treaty allowed for the transfer to Lithuanian authority of some part of the areas of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Although the city itself, as well as its surroundings were actually transferred, the fast pace of the Polish offensive prevented additional territories to be handed over by the Red Army and the disputed area was split into Lithuanian and Polish-controlled parts.

Many historians argue that the main reason behind the Soviet agreement with Lithuania was to weaken Poland and hand the disputed territories to a weaker state, which Lithuania was at the time, in order to reconquer the area more easily after the retreat of the Red Army had halted. Also, the independence of the Baltic States was seen by Lenin as temporary. However, after the Battle of the Niemen River the Red Army was again defeated and Bolshevik Russia was forced to abandon her plans for reincorporation of all the lands lost by the Russian Empire in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

As Russia ceased to be a major player in the area, Polish-Lithuanian relations worsened. In demographic terms Vilnius was one of the most Polonized and Russified[23][24] of Lithuanian cities during 1795-1914 Russian rule,[25] with Lithuanians constituting a mere fraction of the total population: 2% - 2,6% according to Russian (1897), German (1916) and Polish (1919) censuses. The latter two indicated that 50,1% or 56,2% of the inhabitants were Poles, while the Jewish share in the population amounted to 43,5% or 36,1%[26][27][28] (they were conducted after large part of the inhabitants of Vilnius were evacuated to Russia,[29][30] mostly Voronezh[31] because of war in 1915). The Lithuanians nonetheless have strong historical claim to the city (former capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the very center of the formation of medieval Lithuanian state) and refused to recognize any Polish claims to the city and the surrounding area.[25] Lithuanian national activists, for example: Mykolas Biržiška and Petras Klimas, supposed Poles and Belarusians in the Vilnius province to be "Slavicized Lithuanians" who, regardless of their individual preferences, must "return to the language of their blood".[32] After the Bolshevik armies were pushed out of the area, the line reached by the Lithuanian forces before the Poles arrived was secured and diplomatic talks started. However, the negotiations on the future of the disputed area, held under the auspice of the Conference of Ambassadors in Brussels and Paris came to a stalemate and the Polish head of state, Józef Piłsudski feared, that the Entente might want to accept the fait accompli created by the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920. As both countries were officially at peace and the Lithuanian side rejected the idea of a plebiscite, the Poles decided to change the stalemate by creating a fait accompli for their own cause. (See Polish-Lithuanian War)

On October 9, 1920, the Lithuanian-Belarusian Division of the Polish Army under General Lucjan Żeligowski seized the city in a staged mutiny. Vilnius was declared the capital of Republic of Central Lithuania, with Żeligowski as its head of state.[22][33] The negotiations in Brussels continued, but the Polish move did not simplify the situation. Among the plans proposed by the Entente was a creation of a Polish-Lithuanian state based on a cantonal system, with shared control over the disputed area. While this was acceptable to both sides, Poland insisted on inviting the representatives of Central Lithuania to the talks. At the same times the Lithuanian politicians argued that the Central Lithuania was but a puppet state of Poland and rejected the idea. Finally, the talks came to yet another stalemate and no agreement was reached.

Elections in Central Lithuania

On January 8, 1922, general parliamentary elections were held in Central Lithuania. Lithuanian historians claim that many Lithuanian candidates were not registered because they did not speak Polish.[34] Apart from the Lithuanian, Jewish and Belarusian organisations that eventually decided to boycott the voting, Poles, who took part in it supported the incorporation of the area into Poland – with different levels of autonomy. 63.9% of the entire population took part in the voting, but among different ethnic groups the turnout was lower (41% of Belarusians, 15.3% Jews and 8.2% of Lithuanians).[34] Poles were the only major ethnic group in which the majority of people voted. This and the frauds noted by the Pro-Polish Chief of Military control sent by League of Nations Col. Chardigny in his report were the pretexts for Lithuania not to recognise it. Also, the Lithuanian side argued that the election area covered only the territory of Central Lithuania, that is the areas under Lithuanian administration prior to Żeligowski's action, while it should also cover the areas promised to Lithuania in the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920, known as the Vilnius region.

At the first session in the puppet Central Lithuanian Parliament on February 20, 1922, the decision was made to annex the whole area to Poland, with Vilnius becoming the capital of the Wilno Voivodship.

The Council of Ambassadors and the international community (with the exception of Lithuania) recognized Vilnius (Wilno) as part of Poland in 1923.[35][36] The Lithuanian authorities never accepted the status quo and continued to claim sovereignty over the Region of Vilnius. Also, the city itself was declared the constitutional capital of the Lithuanian state while Kaunas was only a temporary capital of Lithuania. Lithuania closed the border and broke all diplomatic relations with Poland. The two countries remained at the de facto state of war until the Polish ultimatum to Lithuania in 1938.

Poland

Poles together with Jews, made up a majority in the city of Vilnius itself. In the years 1920–1939 Poles made up 65% of the population, Jews 28%, 4% Russians, 1% Belarusians 1% Lithuanians.[37] During the 1920s and 1930s around 88 thousand Poles from ethnographic Poland came or were settled to the city.[38][39][40] Most of Lithuanians were forcibly exiled by the Polish authorities or themselves retreated to Lithuania. Most notable cases were deportations of Mykolas Biržiška, Juozapas Kukta and 32 Lithuanians on September 20, 1922, who initially were sentenced to death for political reasons,[41] political imprisonment of Lithuanian cultural figures in the late 1920s: Petras Kraujalis, Pranas Bieliauskas, Kristupas Čibiras, Vincas Taškūnas, Povilas Karazija, Juozas Kairiūkštis, Vytautas Kairiūkštis, Kostas Aleksa and others, political process of May 1925, where 22 Lithuanians, that were under threat of death penalty, but were saved by Tadeusz Wróblewski, etc.[42] In 1936 secret anti-Lithuanian memorial was issued by the Polish administration, that discussed the measures of suppression of Lithuanian minority in Vilnius and the adjacent region, controlled by Poland.[43]

In spite of the unfavorable geopolitical situation (which prevented the trade with the immediate neighbors: Lithuania, Germany and Soviet Russia) life in the town flourished.[44][45] A new trade fair was created in 1928, the Targi Północne. A number of new factories, including modern "Elektrit" radio factory was opened. Much of the development concentrated along the central Mickiewicz Street, where the modern Jabłkowski Brothers department store was opened, equipped with lifts and automatic doors. New radio buildings and towers were erected in 1927, including the site where noted Polish poet and Nobel Prize winner Czesław Miłosz worked. The city's university was reopened under the name Stefan Batory University, and Polish was reintroduced as the language of instruction. By 1931 the city had 195,000 inhabitants, which made it the fifth largest city in Poland. The city became an important center of Polish cultural and scientific life, while economically the rest of the region remained relatively backward. It was claimed that this relative underdevelopment, among other issues, was the reason for difficulties with integrating the region and the city with Lithuania, when it regained Vilnius in 1939.

Vilnius was also an informal capital of Yiddish at that time. The Museum of Jewish culture was founded there in 1919, and YIVO – Institute for Jewish Research, was founded there in 1924. A number of important Jewish cultural institutions including theatres, newspapers and magazines, museums and schools, and Jewish PEN-Club were created before Second World War in Vilnius. Four YIVO directors emigrated to New York.

World War II

In the beginning of the Second World War, Vilnius suffered from continuous German air raids. Despite German pressure, the Lithuanian government categorically declined the suggestions to participate in Germany's aggression against Poland. As a result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and subsequent Soviet invasion, the territories of Eastern Poland were occupied by Red Army, which seized the city following a one-day defence on September 19, 1939. At first, the city was incorporated into the Byelorussian SSR, as the city was a center for Belarusian culture and politics for over a century. The heads of Soviet Belarus moved to the city, Belarusian Language schools were opened, as well a newspaper (Вiленская праўда – The Wilno Pravda).[46] This actions were tolerated by Soviet Union leaders until it was decided to use Vilnius as one of the pretexts to begin interfering in Lithuanian internal affairs.

After talks in Moscow on October 10, 1939 the city and its surrounding areas were transferred to Lithuania according to the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty. In exchange Lithuania agreed to allow Soviet military bases to be established in strategic parts of the country. While the Lithuanian government attempted to refuse these demands, the Russians left them no choice as their troops would enter the country anyway. Only one fifth of Vilnius region was actually given back to Lithuania, despite the fact that the Soviets had recognized the whole region as a part of Lithuania while it was still under Polish control. This reunited Lithuanian Jews, although some people involved in Soviet activities decided to leave.[47] In few days over 3000 Jews left Vilnius for the Soviet Union.[48] Lithuanian authorities entered Vilnius on October 28 and the capital of Lithuania started to be slowly and cautiously transferred there from Kaunas.

Immediately after the Lithuanian army entered the town, at the end of October 1939, a four-day-long anti-Jewish pogrom broke out, in which one person lost their life and some 200 were wounded.[49] As the Lithuanian authorities and police only fueled and supported the pogrom (in fact, it has been claimed that Lithuanian authorities and Fascists had instigated the mostly Polish local population to commit hate crimes against the Jews[50]), the Jewish community asked nearby Russian military units for intervention. The violence only stopped after a group of 35 Soviet tanks briefly re-entered the city and put an end to the pogrom.[51] This prevented further pogroms, that were expected on November 10–11, traditional day of anti-Jewish disturbances in the city.[47]

A month of Soviet rule in Vilnius had catastrophic consequences: the city was starving, the museums and archives robbed, the valuables, industry[52] and historic documents were stolen and transferred to Russia, and many people were imprisoned or deported. Apparently, the Lithuanian government was deliberately slowing down the transfer of the capital back to Vilnius due to fears that the Soviet military presence around the city would enable the Russians to overthrow the Lithuanian government if it were based there.

The Lithuanian authorities started a campaign of de-Polonization of the city, similar policies also targeted the Jews.[49] Immediately upon entering the city, the Lithuanian authorities abolished the use of Polish złoty and ordered the currency to be converted to Lithuanian litas, at 250% devaluation.[49] Soon other discriminating policies followed. During the several months-long period of what the Lithuanians considered the retaking of their capital, while local Poles considered a Lithuanian occupation,[53] roughly 50,000 ethnic Lithuanians were brought to the city. Roughly half of them were settlers from the areas of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union, while the other half were officials from within the pre-war borders of Lithuania.[54]

One of the unfortunate decisions made by Lithuanian authorities in this period was the closure and liquidation of the Stefan Batory University on December 15, 1939. The same decision was taken in case of Society of Friends of Science (est. 1907), which has been permitted to function even under the oppressive Tsarist Russia rule and other Polish scientific institutions. In the process of Lithuanianization Polish language books were removed from stores and Polish language street names were replaced with new, in Lithuanian. Polish offices, schools, charitable social and cultural organizations, stores and businesses were closed. By June 1940 only two institutions in the entire city offered instruction in the Polish language, while roughly 4000 Polish teachers lost their jobs.[54] The refugees, many of whom were Poles and Jews who moved to the city in order to avoid being captured by the Germans, were denied free movement, and by March 28, 1940, all people who had not been citizens of the town in October 1920, were declared to be refugees.[49] Altogether, some 12,000 people were granted Lithuanian citizenship, while 150,000 of the city's inhabitants, mostly Poles, were declared foreigners, excluded from many jobs and even prohibited from riding on trains.[54]

The process of moving the capital was not yet finished when in June 1940, despite Lithuanian resistance, Vilnius was again seized by the Soviet Union and became the capital of the Lithuanian SSR. Approximately 35,000 – 40,000 of the city inhabitants were arrested by the NKVD and sent to gulags or deported to Siberia or Kasakhstan at that time.

In June 1941 the city was again seized by Nazi Germany. In the old town centre two ghettos were set up for the large Jewish population – the smaller of which was "liquidated" by October. The second ghetto lasted until 1943, though its population was regularly decimated in so called Aktionen. A failed Jewish ghetto uprising on September 1, 1943, could not prevent its final destruction. About 95% of the local Jewish population was murdered. Many of them were among 100,000 victims of the mass executions in Paneriai, about 10 kilometers west of the old town centre. Most of the remaining 30,000 victims of the massacre were Poles – POWs, intelligentsia and members of the Armia Krajowa, which at the time was fighting against both Germans and Lithuanians.

Military actions compeletely destroyed very few of Vilnius' buildings and almost all architectural monuments, including all Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox churches, survived. Unfortunately, the decade after the war, both ghetto areas with the famous Great Synagogue and the northern part of German street as well as the whole quarter on Pilies street were torn down.[55]

Soviet occupation

The Germans were forced to leave Vilnius in July 1944 by the combined pressure from the Polish Home Army (Operation Ostra Brama) and the Red Army (Battle of Vilnius (1944)). In 1944–1947 the opponents of the regime, included were captured, interrogated in the NKVD Palace in Lukiškės Square, executed and buried in the Tuskulėnai Manor park.

The Soviets decided that Vilnius was to become again part of the Lithuanian SSR. After the end of World War II the Soviet government, backed by Lithuanian communists and the Polish People's Republic, which demanded the transferring of Poles from the USSR, decided to transfer the Polish population from Lithuania and Belarus.[56] This decision was soon implemented and most of the population was expelled in an operation organized by Soviet and local communist authorities.[56] In some cases the transfer was voluntary, but not all willing people were able to leave because Poles living in rural areas were forced to remain where they had lived.[56][57]

Most of the surviving inhabitants left Vilnius, which had an obvious impact on the city's community and its traditions; what before the war was a Polish-Jewish city with a tiny Lithuanian minority was instantly Lithuanized, with Lithuanians becoming the new majority.[56] Many of the remaining Poles were arrested, murdered or sent to gulags or to remote parts of Soviet empire. These events, coupled with the policy of Russification and immigration of Poles, Russians, Belarussians from other Soviet republics the during post-war years, giving rise the a significant Russophone minority,[56] and slow but steady emigration of the surviving Jews to Israel, had a critical influence on the demographic situation of the city in the 1960s. Vilnius experienced a rapid population upsurge due to inner migration of Lithuanians from the other parts of the country to the capital.

Independent Lithuania

Beginning in 1987 there were massive demonstrations against Soviet rule in the country. On August 23, 1988, more than 200,000 people gathered in Vilnius.[58] On March 11, 1990, the Supreme Council of the Lithuanian SSR announced its independence from the Soviet Union and restored the independent Republic of Lithuania. The Soviets responded on January 9, 1991, by sending in troops. On January 13, during the Soviet Army attack on the State Radio and Television Building and the Vilnius TV Tower, known as the January Events, 14 people were killed and more than 700 were seriously injured. The Soviet Union finally recognized Lithuanian independence in August 1991, after Soviet coup attempt of 1991.

The importance of Vilnius for Belarus remained at the end of the 20th century. In June 1989 Vilnius was the site of the Belarusian Popular Front conference as the Belorussian Soviet authorities would not allow the event to take place in Belarus. At the beginning of 21st century several institutes such as the European Humanities University and the independent sociology center NISEPI persecuted in Belarus by the government of Alexander Lukashenko have found an asylum in Vilnius.

In the years following its independence, Vilnius has been rapidly evolving and improving, transforming from a Soviet dominated enclave into a modern European city in less than 15 years.

See also

- Timeline of Vilnius history

- History of Lithuania

- History of Poland

- Vilnius

- Ethnic history of the Vilnius region

References

- ↑ Vilnius legend

- ↑ "Presentation of the earliest known depiction of the Lithuanian capital". Archives of Slovenia. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ Höfler, Janez (2001). "Noch einmal zur sogenannten böhmischen Straßenkarte in den Sammlungen des Archivs der Republik Slowenien". Acta Historiae Artis Slovenica (in Slovenian and German). Scientific Research Centre, Slovenian Academy of Arts and Sciences. 6. ISSN 1408-0419.

- ↑ various authors (1998). "Legendy wileńskie" (translated from "Vilniaus Legendos") (in Polish). Vilnius: Žuvėrda. p. 21. ISBN 9986-500-30-3.

- 1 2 Zahorski, Władysław (1991) [1925]. Podania i legendy wileńskie (in Polish). illustrated by I.Pinkas 1929. Gdańsk: Graf. p. 22. ISBN 83-85130-22-5.

- ↑ Marszałek-Kawa, Joanna; Renata Runiewicz-Jasińska (2004). Legendy i podania litewskie (in Polish). Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek. p. 26. ISBN 83-7322-789-X.

- 1 2 Jerzy Ochmański, "The National Idea in Lithuania from the 16th to the First Half of the 19th Century: The Problem of Cultural-Linguistic Differentiation", Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Vol. X. No. 3/4. 1986, pp. 310-311.

- ↑ Władysław Czapliński, Władysław IV i jego czasy (Władysław IV and His Times). PW "Wiedza Poweszechna". Warszawa 1976, p. 23

- ↑ Norman Davies, God's Playground: The origins to 1795, Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-231-12817-7, Google Print, p.353

- ↑ Andres Kasekamp, A History of the Baltic States, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 67.

- ↑ Kasekamp, 2010, pp. 68-69

- ↑ Piotr S. Wandycz, The lands of partitioned Poland, 1795–1918, University of Washington Press, 1974, p. 166.

- ↑ Alexei I. Miller. The Romanov Empire and Nationalism: Essays in the Methodology of Historical Research. Central European University Press. 2008. pp. 70, 78, 80.

- ↑ The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897, The city of Vilnius

- ↑ Robert Blobaum, "Feliks Dzierzynski and the SDKPIL a study of the origins of Polish Communism", page 39: the multinational composition of the city - in which the Jewish inhabitants stood as the numerically largest group (40%), followed by the Poles ( 31%), Russians (20%), Belo-russians (4.2%) and the Lithuanians (2.1%).

- 1 2 Michał Gałędek. Ustrój administracji ogólnej na Wileńszczyżnie w okresie międzywojennym (The Organization of the Administration in the Vilnius Land in the Interwar Period), Tabularium, 2012, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Jerzy Borzęcki, The Soviet-Polish Peace of 1921 and the Creation of Interwar Europe, Yale University Press, 2008. pp. 10-11.

- ↑ Borzęcki, 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Borzęcki, 2008, p. 16.

- 1 2 Davies, Norman (2003) [1972]. White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20. First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

- ↑ Borzęcki, 2008, p. 83.

- 1 2 Kasekamp, 2010, p. 104.

- ↑ Merkys, Vytautas (2006). Tautiniai santykiai Vilniaus vyskupijoje 1798-1918 m. Vilnius. p. 479.

- ↑ Staliūnas, Darius (2002). Rusifikacijos samprata XIX a. Lietuvos istorijoje: istoriografija, metodologija, faktografija. Vilnius.

- 1 2 Michael MacQueen, The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, pp. 27–48, 1998,

- ↑ (Polish) Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918–1920 (The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict, 1918–1920), Warsaw, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 83-05-12769-9, pp. 11, 104

- ↑ (Russian) Demoscope.

- ↑ Michał Eustachy Brensztejn (1919). Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od. 1 listopada 1915 r. (in Polish). Biblioteka Delegacji Rad Polskich Litwy i Białej Rusi, Warsaw.

- ↑ Vilniaus patuštinimas // Dabartis, nr. 4, 1915 m., p. 3.

- ↑ Rusijos pabėgėlių vargai // Dabartis, nr. 4, 1915 m. p. 3.

- ↑ Vida PUKIENĖ. Voronežas – lietuvių švietimo židinys Rusijoje Pirmojo pasaulinio karo metais; Istorija. Lietuvos aukštųjų mokyklų mokslo darbai. Vilnius: VPU,2008, t. 70, p. 17–27

- ↑ According to the Lithuanian territorial program, formulated already in 1905, Lithuanian territory included the provinces of Kaunas, Suwałki, Wilno, and Grodno, as well as part of Courland. Lithuanian national activists viewed Polish and Belarusian inhabitants of these provinces as "Slavicized Lithuanians" who must "return to the language of their blood," and argued that individual preferences were, in this case, irrelevant. Borzęcki, 2008, pp. 35, 322 - Notes.

- ↑ Jerzy J. Lerski. Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. 1996, p.309

- 1 2 Zigmantas Kiaupa. The History of Lithuania. 2002, 2004. ISBN 9955-584-87-4

- ↑ Jan. T. Gross, Evolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 3.

- ↑ Borzęcki, 2008, p. 252.

- ↑ "Drugi Powszechny Spis Ludności z dnia 9 XII 1931 r". Statystyka Polski (in Polish). D (34). 1939.

- ↑ "In 1915, before the German occupation, a lot of people together with the Russian army were evacuated to the East. Not all of them returned. After the occupation of the city and the region in 1920 by Poland, 98 thousand Poles came or were settled for Polonization purposes - mostly officials, students, professors, military, pensioners. The majority of them, around 88 thousand, settled in Vilnius, while others were given land, sometimes manors, in the periphery near the city."

- ↑ Žepkaitė, Regina (1990). Vilniaus istorijos atkarpa 1939-1940. Vilnius. p. 54.

- ↑ Vitalija Straviskienė "Lietuvos lenku teritorinis pasiskirstymas ir skaičiaus kaita (1944 m. antrasis pusmetis - 1947 metai) "During the period of the Polish occupation of Vilnius, 98 thousand Poles, 22 thousand of whom were officials, came to Vilnius region."

- ↑ Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. p. 656.

- ↑ Rasa Sperskienė "Advokatas Tadas Vrublevskis – lietuvių politinių bylų dalyvis"

- ↑ Ściśle tajny memorjał Wojewody Wileńskiego Bociańskiego z dnia 11 lutego 1936 r. O posunięciach władz administracji ogólnej w stosunku do mniejszości litewskiej w Polsce oraz o zamierzeniach w tym wględzie na przyszłość : dwa załączniki z d. 11 i 21 marca 1938 r.)

- ↑ Jerzy Remer (1990). Irena Jurzyniec, ed. Wilno (in Polish). Warsaw: Ossolineum. pp. 193–201. ISBN 83-04-03675-4.

- ↑ Edward Raczynski (1941). "5: The Economic Structure". Eastern Poland. London: Polish Research Centre in London.

- ↑ Это вам не 1939 год. Родина (in Russian). Москва: ООО «Родина МЕДИА». September 2006.

- 1 2 Bauer p.108

- ↑ Levin, p. 44

- 1 2 3 4 Yehuda Bauer (1981). American Jewry and the Holocaust. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. pp. 107–115. ISBN 0-8143-1672-7.

- ↑ https://books.google.de/books?id=AUYQ8JQ-iM0C&pg=PA151&lpg=PA151&dq=anti-jewish+pogrom+vilnius+1939&source=bl&ots=8gAIRaF2KC&sig=IUZjKvUo7ZITYfoFpalgggdIFNk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjYhIDT3-_KAhUHpA4KHf-zCoYQ6AEILjAD#v=onepage&q=anti-jewish%20pogrom%20vilnius%201939&f=false

- ↑ Levin, p. 51

- ↑ The whole "Elektrit" factory was transferred to Minsk, together with all the qualified workers (Levin, p. 40)

- ↑ Saulius Sužiedelis (2004). "Historical Sources for Antisemitism in Lithuania". The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Amsterdam-New Jersey: Rodopi. pp. 141–142. ISBN 90-420-0850-4.

- 1 2 3 Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). "Lithuanian collaboration". Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide... McFarland & Company. pp. 160–162. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- ↑ KAROLIS KUČIAUSKAS / KARO PADARINIŲ VERTINIMAS VILNIAUS SENAMIESTYJE 1944 M.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999, Yale University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-300-10586-X, Google Print, p.91-93

- ↑ Stravinskienė, Vitalija (2004). "Poles in Lithuania from the second half of 1944 until 1946: choosing between staying or emigrating to Poland (summary)". Lietuvos istorijos metraštis, 2004 vol 2. The Lithuanian institute of history. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- ↑ Kasekamp, 2010, p. 163.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vilnius. |

- Chronicles of the Vilna Ghetto: wartime photographs & documents – vilnaghetto.com

- History of Vilnius – brief history in timelines.

Bibliography

- Borzecki, Jerzy (2008). The Soviet-Polish Peace of 1921 and the Creation of Interwar Europe. Yale University Press.

- Theodore R. Weeks, FROM “RUSSIAN” TO “POLISH”: Vilna-Wilno 1900–1925

- Kłos, Juliusz (1937). "Wilno", 3rd ed. (in Polish). Wilno.

- (Polish) Jerzy Remer, Wilno, Poznań

- Łossowski, Piotr (2001). Litwa (in Polish). Warszawa: Trio. ISBN 83-85660-59-3.

- Levin, Don (2005). Żydzi wschodnioeuropejscy podczas II wojny światowej (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN PAN. ISBN 83-7399-117-4.

- Venclova, Tomas (2001). Vilnius – guide. Vilnius: Paknio Leidykla. ISBN 9986-830-47-8.