History of bisexuality

This is an article about the history of bisexuality. The subject is inherent with systematic bias, of non-heterosexuality being seen as less worthy than heterosexuality, and of women's sexuality being seen as less worthy, even of being depicted, than that of men. Bisexual erasure has taken place in many cultures so that bisexuality is often not acknowledged or interpreted as homosexuality. In many cultures, bisexuals, especially bisexual women, were never thought to exist.

Sexuality that was non-heteronormative was often not discussed, and only allowed if absolutely necessary. In many cases, although male and female bisexuality has arguably existed in every culture, researchers are often able to only document occurrences tied to scandals, criminal proceedings, private correspondence, and/or artistic renderings.

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greeks did not associate sexual relations with binary labels, as modern Western society does. Men who had male lovers were not identified as homosexual, and may have had wives or other female lovers. See Homosexuality in ancient Greece. Ancient Greek religious texts, reflecting cultural practices, incorporated bisexual themes. The subtexts varied, from the mystical to the didactic.[1]

Spartans thought that love and erotic relationships between experienced and novice soldiers would solidify combat loyalty and unit cohesion, and encourage heroic tactics as men vied to impress their lovers. Once the younger soldiers reached maturity, the relationship was supposed to become non-sexual, but it is not clear how strictly this was followed. There was some stigma attached to young men who continued their relationships with their mentors into adulthood.[1] For example, Aristophanes calls them euryprôktoi, meaning "wide arses", and depicts them like women.[1] The Theban Band, a military of male couples, may have been organized according to the same idea.

Ancient Rome

It was expected and socially acceptable for a freeborn Roman man to want sex with both female and male partners, as long as he took the penetrative role.[2] See Homosexuality in ancient Rome. The morality of the behavior depended on the social standing of the partner, not his sex per se. Both women and young men were considered normal objects of desire, but outside marriage a man was supposed to act on his desires only with slaves, prostitutes (who were often slaves), and the infames. Sex did not determine whether a man's sexual partner was acceptable, but it was considered immoral to have sex with another freeborn man's wife, his marriageable daughter, his underage son, or with the man himself; sexual use of another man's slave was subject to the owner's permission. Lack of self-control, including in managing one's sex life, indicated that a man was incapable of governing others; too much indulgence in "low sensual pleasure" threatened to erode the elite male's identity as a cultured person.[3]

Ancient Japan

Records of men who have sex with men in Japan date back to ancient times. There were few laws restricting sexual behavior in Japan before the early modern period. Anal sodomy was restricted by legal prohibition in 1872, but the provision was repealed only seven years later by the Penal Code of 1880 in accordance with the Napoleonic Code.[4] Historical practices identified by scholars as homosexual include shudō (衆道), wakashudō (若衆道) and nanshoku (男色).

The Japanese term nanshoku (男色?, which can also be read as danshoku) is the Japanese reading of the same characters in Chinese, which literally mean "male colors." The character 色 (color) still has the meaning of sexual pleasure in China and Japan. This term was widely used to refer to some kind of male–male sex in a pre-modern era of Japan. The term shudō (衆道?, abbreviated from wakashudō, the "way of adolescent boys") is also used, especially in older works. References become more numerous in the Heian Period, roughly the 11th century. Some Heian-era diaries contain references to Emperors involved in homosexual relationships and to "handsome boys retained for sexual purposes" by Emperors.[5]

Several writers have noted the strong historical tradition of open bisexuality and homosexuality among male Buddhist institutions in Japan. When the Tendai priest Genshin harshly criticised homosexuality as immoral, others mistook his criticism as having been because the acolyte wasn't one's own.[6][7]

Nanshoku relationships inside monasteries were typically pederastic, that is, an age-structured relationship where the younger partner is not considered adult. The older partner, or nenja ("lover" or "admirer"), would be a monk, priest or abbot, while the younger partner was assumed to be an acolyte (稚児 chigo), who would be a prepubescent or adolescent boy;[8] the relationship would be dissolved once the boy reached adulthood (or left the monastery). Both parties were encouraged to treat the relationship seriously and conduct the affair honorably, and the nenja might be required to write a formal vow of fidelity.[9] Outside of the monasteries, monks were considered to have a particular predilection for male prostitutes, which was the subject of much ribald humor.[10]

There was no religious opposition to homosexuality in Japan in non-Buddhist kami tradition.[11] Tokugawa commentators felt free to illustrate the kami engaging in anal sex with each other.[12] During the Tokugawa period, some of the Shinto gods, especially Hachiman, Myoshin, Shinmei and Tenjin, "came to be seen as guardian deities of nanshoku" (male–male love).[12] Tokugawa-era writer Ihara Saikaku joked that since there are no women for the first three generations in the genealogy of the gods found in the Nihon Shoki, the gods must have enjoyed homosexual relationships—which Saikaku argued was the real origin of nanshoku.[12]

Military same-sex love

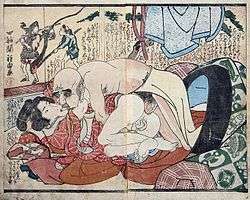

A man reclines with one wakashū and converses with another. Possibly the first nanshoku erotic print, as well as an early example of a hand-colored ukiyo-e print in the shunga (erotic) style. Early 1680s.

Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–94); Ôban format, 10.25" × 15"; Sumi ink and color on paper; Private collection.

From religious circles, same-sex love spread to the warrior (samurai) class, where it was customary for a boy in the wakashū age category to undergo training in the martial arts by apprenticing to a more experienced adult man. The man was permitted, if the boy agreed, to take the boy as his lover until he came of age; this relationship, often formalized in a "brotherhood contract",[13] was expected to be exclusive, with both partners swearing to take no other (male) lovers. This practice, along with clerical pederasty, developed into the codified system of age-structured homosexuality known as shudō, abbreviated from wakashūdo, the "way (do) of wakashū".[14] The older partner, in the role of nenja, would teach the wakashū martial skills, warrior etiquette, and the samurai code of honor, while his desire to be a good role model for his wakashū would lead him to behave more honorably himself; thus a shudō relationship was considered to have a "mutually ennobling effect".[15] In addition, both parties were expected to be loyal unto death, and to assist the other both in feudal duties and in honor-driven obligations such as duels and vendettas. Although sex between the couple was expected to end when the boy came of age, the relationship would, ideally, develop into a lifelong bond of friendship. At the same time, sexual activity with women was not barred (for either party), and once the boy came of age, both were free to seek other wakashū lovers.

Like later Edo same-sex practices, samurai shudō was strictly role-defined; the nenja was seen as the active, desiring, penetrative partner, while the younger, sexually receptive wakashū was considered to submit to the nenja's attentions out of love, loyalty, and affection, rather than sexual desire. Among the samurai class, adult men were (by definition) not permitted to take the wakashū role; only preadult boys (or, later, lower-class men) were considered legitimate targets of homosexual desire.[16] In some cases, shudō relationships arose between boys of similar ages, but the parties were still divided into nenja and wakashū roles.

Middle class same-sex love

As Japanese society became pacified, the middle classes adopted many of the practices of the warrior class, in the case of shudō giving it a more mercantile interpretation. Male prostitutes (kagema), who were often passed off as apprentice kabuki actors and who catered to a mixed male and female clientele, did a healthy trade into the mid-19th century despite increasing restrictions.[17] Many such prostitutes, as well as many young kabuki actors, were indentured servants sold as children to the brothel or theatre, typically on a ten-year contract.[18] Relations between merchants and boys hired as shop staff or housekeepers were common enough, at least in the popular imagination, to be the subject of erotic stories and popular jokes.[19] Young kabuki actors often worked as prostitutes off-stage, and were celebrated in much the same way as modern media stars are today, being much sought after by wealthy patrons, who would vie with each other to purchase their favors.[20] Onnagata (female-role) and wakashū-gata (adolescent boy-role) actors in particular were the subject of much appreciation by both male and female patrons,[21] and figured largely in nanshoku shunga prints and other works celebrating nanshoku, which occasionally attained best-seller status.[22]

Male prostitutes and actor-prostitutes serving male clientele were originally restricted to the wakashū age category, as adult men were not perceived as desirable or socially acceptable sexual partners for other men. During the 17th century, these men (or their employers) sought to maintain their desirability by deferring or concealing their coming-of-age and thus extending their "non-adult" status into their twenties or even thirties; this eventually led to an alternate, status-defined shudō relationship which allowed clients to hire "boys" who were, in reality, older than themselves.[23] This evolution was hastened by mid-17th century bans on the depiction of the wakashū's long forelocks, their most salient age marker, in kabuki plays; intended to efface the sexual appeal of the young actors and thus reduce violent competition for their favors, this restriction eventually had the unintended effect of de-linking male sexual desirability from actual age, so long as a suitably "youthful" appearance could be maintained.[24]

Art of same-sex love

These activities were the subject of countless literary works, most of which remain to be translated. However, English translations are available for Ihara Saikaku who created a bisexual main character in The Life of An Amorous Man (1682), Jippensha Ikku who created an initial gay relationship in the post-publication "Preface" to Shank's Mare (1802 et seq), and Ueda Akinari who had a homosexual Buddhist monk in Tales of Moonlight and Rain (1776). Likewise, many of the greatest artists of the period, such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, prided themselves in documenting such loves in their prints, known as ukiyo-e, pictures of the floating world, and where they had an erotic tone, shunga, or pictures of spring.[25]

Nanshoku was not considered incompatible with heterosexuality; books of erotic prints dedicated to nanshoku often presented erotic images of both young women (concubines, mekake, or prostitutes, jōrō) as well as attractive adolescent boys (wakashū) and cross-dressing youths (onnagata). Indeed, several works suggest that the most "envious" situation would be to have both many jōrō and many wakashū.[26] Likewise, women were considered to be particularly attracted to both wakashū and onnagata, and it was assumed that these young men would reciprocate that interest.[26] Therefore, both the typical practitioners of nanshoku and the young men they desired would be considered bisexual in modern terminology.[27]

1850 to 1950

The word "bisexual" was first used in its modern sense by the American neurologist Charles Gilbert Chaddock to describe someone that engaged in sexual activity with both male and female partners in his 1892 translation of Kraft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis. Prior to this, "bisexual" was usually used to mean hermaphroditic. Under any label, openly bisexual people were rare in early American life. One notable exception was the openly bisexual poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, who received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver in 1923.[28] Furthermore, the poet Walt Whitman is usually described by biographers as either bisexual or homosexual in his feelings and attractions.

Early film, being a cutting-edge medium, also provided opportunity for bisexuality to be expressed. In 1914 the first documented appearance of bisexual characters (female and male) in an American motion picture occurred in A Florida Enchantment, by Sidney Drew.[29] However, due to the censorship legally required by the Hays Code, the word bisexual could not be mentioned and almost no bisexual characters appeared, in American film from 1934 until 1968.[29]

Bisexual Americans were given some visibility in the research of Alfred Kinsey (who was himself bisexual) and his colleagues in the late 1940s and early 1950s; they found that 28% of women and 46% of men had responded erotically to or were sexually active with people of both sexes.[30]

Their research also found that 11.6% of white males (ages 20–35) had about equal heterosexual and homosexual experience/response throughout their adult lives, and that 7% of single females (ages 20–35) and 4% of previously married females (ages 20–35) had about equal heterosexual and homosexual experience/response for this period of their lives.[31][32] As a result of this research, the earlier meanings of the word "bisexual" were largely displaced by the modern meaning of being attracted to both sexes.[33] However, Kinsey himself disliked the use of the term bisexual to describe individuals who engage in sexual activity with both sexes, preferring to use "bisexual" in its original, biological sense as hermaphroditic, and saying, "Until it is demonstrated [that] taste in a sexual relation is dependent upon the individual containing within his [sic] anatomy both male and female structures, or male and female physiological capacities, it is unfortunate to call such individuals bisexual" (Kinsey et al., 1948, p. 657).[34]

1950 to present

1960s

LGBT political activism became more prominent in this decade. In 1966 bisexual activist Robert A. Martin (aka Donny the Punk) founded the Student Homophile League at Columbia University and New York University. In 1967 Columbia University officially recognized this group, thus making them the first college in the United States to officially recognize a gay student group.[35] Activism on behalf of bisexuals in particular also began to grow, especially in San Francisco. One of the earliest organizations for bisexuals, the Sexual Freedom League in San Francisco, was facilitated by Margo Rila and Frank Esposito beginning in 1967.[35] Two years later, during a staff meeting at a San Francisco mental health facility serving LGBT people, nurse Maggi Rubenstein came out as bisexual. Due to this, bisexuals began to be included in the facility's programs for the first time.[35]

The Stonewall Rebellion, considered the beginning of the modern LGBT rights movement, occurred at the Stonewall bar in 1969. Bar patrons, including bisexuals, stood up to the police during a raid.[35] In commemoration of this, the next year the first LGBT pride march was held. Bisexual activist Brenda Howard is known as the "Mother of Pride" for her work in coordinating this march. Howard also originated the idea for a week-long series of events around Pride Day which became the genesis of the annual LGBT Pride celebrations that are now held around the world every June.[36][37] Additionally, Howard along with bisexual activist Robert A. Martin (aka Donny the Punk) and L. Craig Schoonmaker are credited with popularizing the word "Pride" to describe these festivities.[38] As bisexual activist Tom Limoncelli put it, "The next time someone asks you why LGBT Pride marches exist or why [LGBT] Pride Month is June tell them 'A bisexual woman named Brenda Howard thought it should be.'"

1970s

Bisexuals became more prominent in the media in the 1970s. In 1972 bisexual activist Don Fass founded the National Bisexual Liberation group in New York City, which issued The Bisexual Expression, most likely the earliest bisexual newsletter.[35] In 1973 bisexual activist Woody Glenn was interviewed by a radio show of the National Organization for Women on WICC in Bridgeport, Connecticut.[35] In 1974, both Newsweek and Time Magazine ran stories on "bisexual chic," bringing bisexuality to mainstream attention as never before.[35] In 1976 the landmark book View from Another Closet: Exploring Bisexuality in Women, by Janet Mode, was published.[39]

Bisexuals were also important contributors to the larger LGBT rights movement. In 1972, Bill Beasley, a bisexual activist in the Civil Rights Movement as well as the LGBT movement, was the core organizer of the first Los Angeles Gay Pride March. He was also active with the Gay Liberation Front.[35] In 1975, activist Carol Queen came out as bisexual and organized GAYouth in Eugene, Ore.[35] In 1977 Alan Rockway, a psychologist and bisexual activist, co-authored America's first successful gay rights ordinance put to public vote, in Dade County, Florida. Anita Bryant campaigned against the ordinance, and Rockway began a boycott of Florida orange juice, which she advertised, in response. The San Francisco Bisexual Center also helped sponsor a press conference with lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, and pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock, in opposition to Bryant. Bisexual activist Alexei Guren founded the Gay Teen Task Force in Miami, Fla., in response to Bryant's campaign. The Florida Citrus Commission canceled her contract as a direct response to this pressure.[35] Also in 1979, Dr. Marvin Colter founded ARETE, a support and social group for bisexuals in Whittier, Calif., which marched in the 1983 Los Angeles Gay Pride Parade and had a newsletter.[35] In 1979 A. Billy S. Jones, a bisexual founding member of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, helped organize the first black gay delegation to meet with President Jimmy Carter's White House staff. Jones was also a core organizer of the 1979 March On Washington for Gay and Lesbian Rights, and “Third world conference: When will the ignorance end?,” the first national conference for gay and lesbian people of color.[35]

The bisexual movement had its own successes as well. Most notably, in 1972 a Quaker group, the Committee of Friends on Bisexuality, issued the “Ithaca Statement on Bisexuality” supporting bisexuals.[40] The Statement, which may have been "the first public declaration of the bisexual movement" and "was certainly the first statement on bisexuality issued by an American religious assembly," appeared in the Quaker Friends Journal and The Advocate in 1972.[41][42][43]

In 1976 Harriet Levi and Maggi Rubenstein founded the San Francisco Bisexual Center.[35] It was the longest surviving bisexual community center, offering counseling and support services to Bay Area bisexuals, as well as publishing a newsletter, The Bi Monthly, from 1976 to 1984.[35] In 1978, bisexual activist Dr. Fritz Klein introduced the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid in his book The bisexual option: A concept of one-hundred percent intimacy, in which he examined the incidence and nature of bisexuality, the attitudes of bisexual persons, and the rewards of bisexuality.[35] Bisexual activism also began to spread beyond the coasts, as from 1978 until 1979, several Midwestern bisexual groups were created, such as One To Five (founded by Scott Bartell and Gary Lingen for Minneapolis/St.Paul, Minn), BI Women Welcome in Minneapolis, The BI Married Men's Group in the Detroit suburbs, and BI Ways in Chicago.[35]

1980s

In the 1980s AIDS began to affect the LGBT community, and bisexual people took an important role in combating it. In 1981 bisexual activists David Lourea and Cynthia Slater presented safer-sex education in bathhouses and BDSM clubs in San Francisco. Also in 1981, bisexual activist Alexei Guren, on the founding board of the Health Crisis Network (now CareResource) in Miami, Fla., began outreach and advocacy for Latino married men who have sex with men.[35] In 1984, bisexual activist David Lourea finally persuaded the San Francisco Department of Public Health to recognize bisexual men in their official AIDS statistics (the weekly “New AIDS cases and mortality statistics” report), after two years of campaigning. Health departments throughout the United States began to recognize bisexual men because of this, whereas before they had mostly only recognized gay men.[35] Bisexual activists also fought for the recognition of women in the AIDS epidemic. From 1984 until 1986, bisexual activist Veneita Porter, of the Prostitute’s Union of Massachusetts and COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), advocated for women, transgender people, and injection drug users with AIDS.[35] In 1985, HIV-Positive bisexual activist Cynthia Slater organized the first Women’s HIV/AIDS Information Switchboard.[35] This sort of activism was particularly important for bisexuals as they were often blamed for spreading AIDS to their heterosexual partners. For example, in 1987, Newsweek portrayed bisexual men as “the ultimate pariahs” of the AIDS epidemic, and bisexual activist and person with AIDS Alan Rockway of BiPOL was quoted speaking against the stereotype.[35] An October 1989 Cosmopolitan magazine article that stereotyped bisexual men as dishonest spreaders of AIDS led to a letter-writing campaign by the New York Area Bisexual Network (NYABN). Cosmopolitan has printed no articles defaming bisexuals since the campaign.[35]

The bisexual movement enjoyed some important firsts during the 1980s. The Boston Bisexual Women's Network, the oldest existing bisexual women's group, was founded in 1983 and began publishing their bi-monthly newsletter, BI Women. It is the longest-existing bisexual newsletter in the US.[35] Also in 1983, BiPOL, the first and oldest bisexual political organization, was founded in San Francisco by bisexual activists Autumn Courtney, Lani Ka'ahumanu, Arlene Krantz, David Lourea, Bill Mack, Alan Rockway, and Maggi Rubenstein.[35] In 1984, BiPOL sponsored the first bisexual rights rally, outside the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. The rally featured nine speakers from civil rights groups allied with the bisexual movement.[35] Also in 1984, the First East Coast Conference on Bisexuality (which was also the first regional bisexual conference in the US) was held at the Storrs School of Social Work at the University of Connecticut, with about 150 people participating.[35] Participants in the conference then founded the East Coast Bisexual Network in 1985, which later was renamed the Bisexual Resource Center (BRC) in 1993. In 1987, the East Coast Bisexual Network established the first Bisexual History Archives with bisexual activist Robyn Ochs’ initial collection; archivist Clare Morton hosted researchers.[35] Also in 1987, the Bay Area Bisexual Network, the oldest and largest bisexual group in the San Francisco Bay Area, was founded by Lani Ka'ahumanu, Ann Justi and Maggi Rubenstein.[44]

In 1988, Gary North published the first national bisexual newsletter, called Bisexuality: News, Views, and Networking.[35] In 1989 Cliff Arnesen testified before the U.S. Congress on behalf of bisexual, lesbian, and gay veteran's issues.[45] He was the first veteran to testify about bisexual, lesbian, and gay issues and the first openly non-heterosexual veteran to testify on Capitol Hill about veteran's issues in general.[45] He testified on May 3rd, 1989, during formal hearings held before the U.S. House Committee on Veterans Affairs: Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations.[46] He also testified before the same Subcommittee on May 16, 1990, as part of an HIV/AIDS panel.[46][47]

Bisexual people also continued to be active in the larger LGBT movement. The first BiCon UK (a get-together in the United Kingdom for bisexuals, allies and friends) was held in 1984.[48] In 1986 BiPOL's Autumn Courtney was elected co-chair of San Francisco's Lesbian Gay Freedom Day Pride Parade Committee; she was the first openly bisexual person to hold this sort of position in the United States.[35] In 1987 a group of 75 bisexuals marched in the 1987 March On Washington For Gay and Lesbian Rights, which was the first nationwide bisexual gathering. The article "The Bisexual Movement: Are We Visible Yet?", by Lani Ka'ahumanu, appeared in the official Civil Disobedience Handbook for the March. It was the first article about bisexuals and the emerging bisexual movement to be published in a national lesbian or gay publication.[49] The North American Bisexual Network, the first national bisexual organization, was first thought of at this gathering, though not founded until three years later (see below.) NABN would later change its name to BiNet USA.[35] Also in 1987, Barney Frank became the first U.S. congressman to come out as gay of his own volition; he was inspired in part by the death of Stewart McKinney, a closeted bisexual Republican representative from Connecticut.[50][51] Frank told The Washington Post that after McKinney's death there was, "An unfortunate debate about 'Was he or wasn't he? Didn't he or did he?' I said to myself, I don't want that to happen to me." [50][51]

1990s

The oldest national bisexuality organization in the United States, BiNet USA, was founded in 1990. It was originally called the North American Multicultural Bisexual Network (NAMBN), and had its first meeting at the first National Bisexual Conference in America.[52][52][53] This first conference was held in San Francisco, and sponsored by BiPOL. Bisexual health was one of eight workshop tracks at the conference, and the “NAMES Project” quilt was displayed with bisexual quilt pieces. Over 450 people attended from 20 states and 5 countries, and the mayor of San Francisco sent a proclamation "commending the bisexual rights community for its leadership in the cause of social justice," and declaring June 23, 1990 Bisexual Pride Day.[35] The conference also inspired attendees from Dallas to create the first bisexual group in Texas, called BiNet Dallas.[35]

The bisexual movement also became more accepted as part of established institutions. In 1990, Susan Carlton offered the first academic course on bisexuality in America at UC Berkeley, and in 1991, psychologists Sari Dworkin and Ron Fox became the founding co-chairs of the Task Force on Bisexual Issues of Division 44, the gay and lesbian group in the American Psychological Association.[35] In 1997, bisexual activist and psychologist Pat Ashbrook pioneered a national model for LGBT support groups within the Veterans Administration hospital system.[35]

Bisexual literature became more prominent in the 1990s. In 1991, the Bay Area Bisexual Network began publishing the USA's first national bisexual quarterly magazine, Anything That Moves: Beyond The Myths Of Bisexuality, founded by Karla Rossi, who was the managing editor of the editorial collective until 1993.[35][44] 1991 also saw the publication of one of the seminal books in the history of the modern bisexual rights movement, Bi Any Other Name: Bisexual People Speak Out, an anthology edited by Loraine Hutchins and Lani Ka'ahumanu. After this anthology was forced to compete (and lost) in the Lambda Literary Awards under the category Lesbian Anthology, and in 2005, Directed by Desire: Collected Poems[54] a posthumous collection of the bisexual Jamaican American writer June Jordan's work had to compete (and won) in the category "Lesbian Poetry",[55] BiNet USA led the bisexual community in a multi-year campaign eventually resulting in the addition of a Bisexual category, starting with the 2006 Awards. In 1995, Harvard Shakespeare professor Marjorie Garber made the academic case for bisexuality with her book Vice Versa: Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life, in which she argued that most people would be bisexual if not for "repression, religion, repugnance, denial, laziness, shyness, lack of opportunity, premature specialization, a failure of imagination, or a life already full to the brim with erotic experiences, albeit with only one person, or only one gender."[56] Bi Community News began publishing as a monthly print journal in the UK in 1994. In 1997, bisexual activist Dr. Fritz Klein founded the Journal of Bisexuality, the first academic, quarterly journal on bisexuality.[35] However, other media proved more mixed in terms of representing bisexuals. In 1990, a film with a relationship between two bisexual women, called Henry and June, became the first film to receive the NC-17 rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA).[57] But in 1993, bisexual activist Sheela Lambert wrote, produced, and hosted the first television series by and for bisexuals, called Bisexual Network. It aired for 13 weeks on NYC Public Access Cable.[35]

Regional organizations in the bisexual movement also began to have more impact. In 1992 the Bisexual Connection (Minnesota) sponsored the First Annual Midwest Regional Bisexual Conference, called "BECAUSE (Bisexual Empowerment Conference: A Uniting, Supportive Experience)."[35] That year Minnesota changed its State Civil Rights Law to grant the most comprehensive civil rights protections for bisexual, lesbian, gay, and transgender people in the country. Minnesota's bisexual community had united with lesbian, gay, and transgender groups to lobby for this statute.[35] Also in 1992, the South Florida Bisexual Network (founded in 1989) and the Florida International University's Stonewall Students Union co-sponsored the First Annual Southeast Regional Bisexual Conference. Thirty-five people from at least four southeastern states attended.[35] In 1993 the First Annual Northwest Regional Conference was sponsored by BiNet USA, the Seattle Bisexual Women's Network, and the Seattle Bisexual Men's Union. It was held in Seattle, and fifty-five people representing Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Montana, and British Columbia attended.[35] In the UK, BiPhoria was formed in 1994, the oldest bi organisation extant in the UK today.

An important event in the LGBT rights movement in this decade was the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. As a result of lobbying by BiPOL (San Francisco), openly bisexual people held key leadership roles in local and regional organizing for the March, and for the first time bisexuals were included in the title of the March. Also, openly bisexual activist and author Lani Ka'ahumanu spoke at the rally, and over 1,000 people marched with the bisexual group. Coinciding with the March, BiNet USA, the Bisexual Resource Center (BRC), and the Washington, DC-based Alliance of Multicultural Bisexuals (AMBi) sponsored the Second National Conference Celebrating Bisexuality in Washington, DC. Over than 600 people attended from the US and Europe, making it at the time the largest Bisexual Conference ever held.[35]

Several important surveys concerning bisexuality were conducted around this time. In 1993, Ron Fox authored the first large scale research study on bisexual identity, and established and maintained a comprehensive bibliography on bi research.[35] Also in 1993, The Janus Report on Sexual Behavior showed that 5 percent of men and 3 percent of women considered themselves bisexual.[58] In 1995 BiNet USA Bisexual Youth Initiative, Fayetteville, N.C., developed and mailed a national survey to LGBT youth programs. The survey was published and sent back to agencies, offering assistance to improve services to bisexual youth.[35]

The concept of bisexual pride became more widespread in the late 1990s. At an LGBT PrideFest in Connecticut in 1997, Evelyn Mantilla came out as America's first openly bisexual state official.[59][60] The next year, the Bisexual Pride flag was designed by Michael Page (it was unveiled on Dec 5th, 1998 [61]), and in 1999, the first Celebrate Bisexuality Day was organized by Michael Page, Gigi Raven Wilbur, and Wendy Curry. It is now observed every September 23.[35]

2000-2010

Bisexual people had notable accomplishments in the LGBT rights movement at this time. In 2001, the American Psychological Association (APA)’s “Guidelines on psychotherapy with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients” stated “homosexuality and bisexuality are not a mental illness"; bisexual activist Ron Fox served on the task force that produced the guidelines.[35] In 2002, Pete Chvany, Luigi Ferrer, James Green, Loraine Hutchins and Monica McLemore presented at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Health Summit, held in Boulder, Colorado, marking the first time bisexual people, transgender people, and intersex people were recognized as co-equal partners on the national level rather than gay and lesbian “allies” or tokens.[35] Also in 2002, bisexual activist Robyn Ochs delivered the first bi-focused keynote during the National Association of Lesbian and Gay Addiction Professionals.[35] In 2003, the Union for Reform Judaism retroactively applied its pro-rights policy on gays and lesbians to the bisexual and transgender communities, issuing a resolution titled, "SUPPORT FOR THE INCLUSION AND ACCEPTANCE OF THE TRANSGENDER AND BISEXUAL COMMUNITIES." [62] In 2005, bisexual scholars and activists mobilized with The Task Force, GLAAD and BiNet USA to meet with New York Times science section editor and researcher Brian Dodge to respond to misinformation the paper had published on a study about bisexual men.[35] The study, entitled Sexual Arousal Patterns of Bisexual Men, by the controversial researcher J. Michael Bailey, allegedly "proved" that bisexual men did not exist. With little critical examination, various media celebrities and outlets jumped on the band-wagon[63] and claimed to have "solved" the "problem of bisexuality" by declaring it to be non-existent, at least in men. Further studies, including improved follow-up research led by Michael Bailey, proved this to be false.[64] Also in 2005, the Queens Chapter of PFLAG announced the creation of the "Brenda Howard Memorial Award".[65] This was the first time a major American LGBT organization named an award after an openly bisexual person. On October 11, 2009 in Washington, D.C., the National Equality March was held, calling for equal protection for bisexual, lesbian, gay, and transgender people in all matters governed by civil law in all states and districts. There was a specific bisexual, pansexual and queer-identified contingent that was organized as a part of the March.[66] Several bisexual groups came together and marched, including BiNet USA, New York Area Bisexual Network, DC Bi Women and BiMA DC.[67] There were also four out bisexual speakers at the National Equality March rally: Michael Huffington, Lady Gaga, Chloe Noble, and Penelope Williams. In October 2009, LGBT activist Amy Andre[68] was appointed as executive director of the San Francisco Pride Celebration Committee, making her San Francisco Pride's first openly bisexual woman of color executive director.[69][70]

Significant reports about bisexuals were also released in this decade. In 2002, a survey in the United States by National Center for Health Statistics found that 1.8 percent of men ages 18–44 considered themselves bisexual, 2.3 percent homosexual, and 3.9 percent as "something else". The same study found that 2.8 percent of women ages 18–44 considered themselves bisexual, 1.3 percent homosexual, and 3.8 percent as "something else".[58] A 2007 report said that 14.4% of young US women identified themselves as bisexual/lesbian, with 5.6% of the men identifying as gay or bisexual.[71] Also in 2007, an article in the 'Health' section of The New York Times stated that "1.5 percent of American women and 1.7 percent of American men identify themselves [as] bisexual."[72]

In 2008 Kate Brown was elected as the Oregon Secretary of State, becoming America's first openly bisexual statewide officeholder.[73][74][75][76]

2010 to present

In 2011, one of the demands of 2009's National Equality March was met as the "Don't Ask Don't Tell" policy was ended, allowing bisexuals, lesbians, and gay men in the U.S. military to be open about their sexuality.[77][78][79][80]

More important reports on bisexual people were released in the early 2010s. In 2011, San Francisco’s Human Rights Commission released a report on bisexual visibility, titled “Bisexual Invisibility: Impacts and Regulations.” This was the first time any governmental body released such a report. The report showed, among other things, that self-identified bisexuals made up the largest single population within the LGBT community in the United States. In each study included in the report, more women identified as bisexual than lesbian, though fewer men identified as bisexual than gay.[81] Also in 2011, a longitudinal study of sexual minority women (lesbian, bisexual, and unlabeled) found that over 10 years, “more women adopted bisexual/unlabeled identities than relinquished them.” Of those who began the study identifying as bisexual, 92% identified as bisexual or unlabeled 10 years later, and 61% of those who began as unlabeled identified as bisexual or unlabeled 10 years later.[81] In 2012, the Bisexuality Report, the first report of its kind in the United Kingdom, was issued.[82] This report, devised by Jen Yockney (editor of Bi Community News) and led by Meg-John Barker (Senior Lecturer in Psychology, OU), Rebecca Jones (Lecturer, Health & Social Care, OU), Christina Richards, and Helen Bowes-Catton and Tracey Plowman (of BiUK) summarizes national and international evidence and brings out recommendations for bisexual inclusion in the future.[82] It was credited[83] with changing attitudes to bisexual inclusion in LGB work for both the UK civil service and LGBT charities.

In September 2012 Berkeley, California became the first city in America to officially proclaim a day recognizing bisexuals.[84] The Berkeley City Council unanimously and without discussion declared Sept. 23 as Bisexual Pride and Bi Visibility Day.[84] In 2013 on Bisexual Pride and Bi Visibility Day, the White House held a closed-door meeting with about 30 bisexual advocates so they could meet with government officials and discuss issues of specific importance to the bisexual community; this was the first bi-specific event ever hosted by any White House.[85][86] Another important contribution to bisexual visibility came in 2014, when the Bisexual Research Collaborative on Health (BiRCH) was founded to search for ways to raise public awareness of bisexual health issues, as well as to continue high-level discussions of bisexual health research and plan a national (American) conference.[87][88] Also in 2014, the book Bisexuality: Making the Invisible Visible in Faith Communities, the first book of its kind, was published.[89] It is by Marie Alford-Harkey and Debra W. Haffner.[89]

As for politics, in November 2012 Kyrsten Sinema was elected to the House of Representatives, becoming the first openly bisexual member of Congress in American history.[90] Later, in 2015 Kate Brown became the first openly bisexual governor in the United States, as governor of Oregon when the old governor resigned.[91][92][93] Kate Brown was elected as governor of Oregon in 2016, and thus became the first openly bisexual person elected as a United States governor (and indeed the first openly LGBT person elected as such).[94]

In 2015, biphobia was added to the name of the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia, previously the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia.[95]

Timeline of bisexual history

- 1892: The word "bisexual" is first used in its current sense in Charles Gilbert Chaddock's translation of Kraft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis.[96]

- 1914: The first documented appearance of bisexual characters (female and male) in an American motion picture occurred in A Florida Enchantment, by Sidney Drew.[29]

- 1966: Robert A. Martin (aka Donny the Punk) (nee Robert Martin, 1946-1996) founded the Student Homophile League at Columbia University and New York University; in 1967 Columbia University was the first University in the United States to officially recognize a gay student group.[97]

- 1969: The Stonewall Rebellion, considered the beginning of the modern LGBT rights movement, occurred at the Stonewall bar in 1969. Bar patrons, including bisexuals, stood up to the police during a raid.[35]

- 1970: In commemoration of the Stonewall Rebellion, the first LGBT pride march was held. Brenda Howard is known as the "Mother of Pride" for her work in coordinating this march. Howard also originated the idea for a week-long series of events around Pride Day which became the genesis of the annual LGBT Pride celebrations that are now held around the world every June.[36][37] Additionally, Howard along with Robert A. Martin (aka Donny the Punk) and L. Craig Schoonmaker are credited with popularizing the word "Pride" to describe these festivities.[38]

- 1972: Bill Beasley, a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement, was the core organizer of first Los Angeles Gay Pride March and active with the Gay Liberation Front.[98]

- 1972: A Quaker group, the Committee of Friends on Bisexuality, issued the "Ithaca Statement on Bisexuality" supporting bisexuals.[99]

The Statement, which may have been "the first public declaration of the bisexual movement" and "was certainly the first statement on bisexuality issued by an American religious assembly," appeared in the Quaker Friends Journal and The Advocate in 1972.[41][42][43]

- Presently Quakers have varying opinions on LGBT people and rights, with some Quaker groups more accepting than others.[100]

- 1974: In New York City Dr. Fritz Klein founded the Bisexual Forum, the first support group for the bisexual community.[101][102]

- 1977: Alan Rockway co-authored the first successful gay rights ordinance put to public vote in America, in Dade County, Florida. When Anita Bryant initiated the anti-gay "Save Our Children" campaign in response to the ordinance, Dr. Rockway conceived of and initiated a national "gaycott" of Florida orange juice. The Florida Citrus Commission canceled Ms. Bryant's million dollar contract as a result of the "gaycott." [97]

- 1978: Dr. Fritz Klein first described the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid (KSOG), which attempts to measure sexual orientation by expanding upon the earlier Kinsey scale, in his 1978 book The Bisexual Option. [103][104][105][106]

- 1979: A. Billy S. Jones, a founding member of National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, helped organize the first black gay delegation to meet with President Carter's White House staff. Jones was also a core organizer of the 1979 March On Washington for Gay and Lesbian Rights, and was a key organizer for "Third world conference: When will the ignorance end?" the first national gay and lesbian people of color conference.[97]

- 1983: The Boston Bisexual Women's Network, the oldest existing bisexual women's group, was founded in 1983 and began publishing their bi-monthly newsletter, BI Women. It is the longest-existing bisexual newsletter in the US.[35]

- 1983: BiPOL, the first and oldest bisexual political organization, was founded in San Francisco by Autumn Courtney, Lani Ka'ahumanu, Arlene Krantz, David Lourea, Bill Mack, Alan Rockway, and Maggi Rubenstein.[35]

- 1984: BiPOL sponsored the first bisexual rights rally, which was held outside the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. The rally featured nine speakers from civil rights groups allied with the bisexual movement.[35]

- 1984: A. Billy S. Jones helped organize the first federally funded national "AIDS in the Black Community Conference" in Washington, D.C.[98]

- 1984: The First East Coast Conference on Bisexuality (which was also the first regional bisexual conference in the US) was held at the Storrs School of Social Work at the University of Connecticut, with about 150 people participating.[35]

- 1985: The Bisexual Resource Center (BRC) was founded.[107]

- 1985: Cynthia Slater (1945-1989), an early outspoken bisexual and HIV positive woman, organized the first Women's HIV/AIDS Information Switchboard.[98]

- 1985: The first BiCon UK (a get-together in the United Kingdom for bisexuals, allies and friends) was held.[48]

- 1986: BiPOL's Autumn Courtney was elected co-chair of San Francisco's Lesbian Gay Freedom Day Pride Parade Committee; she was the first openly bisexual person to hold this sort of position in the United States.[35]

- 1987: Veneita Porter, director of the New York State Office of AIDS Discrimination, helped design the first educational projects and trainings for state workers, hearing judges and legal staff.[98]

- 1987: The New York Area Bisexual Network (NYABN) was founded.[108]

- 1987: The East Coast Bisexual Network established the first Bisexual History Archives with Robyn Ochs' initial collection; archivist Clare Morton hosted researchers.[35]

- 1987: The Bay Area Bisexual Network, the oldest and largest bisexual group in the San Francisco Bay Area, was founded by Lani Ka'ahumanu, Ann Justi and Maggi Rubenstein.[44]

- 1987: A group of 75 bisexuals marched in the 1987 March On Washington For Gay and Lesbian Rights, which was the first nationwide bisexual gathering. The article "The Bisexual Movement: Are We Visible Yet?", by Lani Ka'ahumanu, appeared in the official Civil Disobedience Handbook for the March.[35] It was the first article about bisexuals and the emerging bisexual movement to be published in a national lesbian or gay publication.[49]

- 1988: Gary North published the first national bisexual newsletter, called Bisexuality: News, Views, and Networking.[35]

- 1989: Openly bisexual veteran Cliff Arnesen testified before the U.S. Congress on behalf of bisexual, lesbian, and gay veteran's issues.[45] He was the first veteran to testify about bisexual, lesbian, and gay issues and the first openly non-heterosexual veteran to testify on Capitol Hill about veteran's issues in general.[45] He testified on May 3, 1989, during formal hearings held before the U.S. House Committee on Veterans Affairs: Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations.[46]

- 1990: The North American Bisexual Network, the first national bisexual organization, was founded. NABN would later change its name to BiNet USA.[35] It had its first meeting at the first National Bisexual Conference in America.[52][52][53] This first conference was held in San Francisco, and sponsored by BiPOL. Bisexual health was one of eight workshop tracks at the conference, and the "NAMES Project" quilt was displayed with bisexual quilt pieces. Over 450 people attended from 20 states and 5 countries, and the mayor of San Francisco sent a proclamation "commending the bisexual rights community for its leadership in the cause of social justice," and declaring June 23, 1990 Bisexual Pride Day.[35] The conference also inspired attendees from Dallas to create the first bisexual group in Texas, called BiNet Dallas.[35]

- 1990: Susan Carlton offered the first academic course on bisexuality in America at UC Berkeley.[97]

- 1990: A film with a relationship between two bisexual women, called Henry and June, became the first film to receive the NC-17 rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA).[57]

- 1991: Psychologists Sari Dworkin and Ron Fox became the founding co-chairs of the Task Force on Bisexual Issues of Division 44, the gay and lesbian group in the American Psychological Association.[35]

- 1991: Liz Highleyman co-founded the Boston ACT UP IV League needle exchange, one of the first in the US.[98]

- 1991: The Bay Area Bisexual Network began publishing the first national bisexual quarterly magazine, Anything That Moves: Beyond The Myths Of Bisexuality, founded by Karla Rossi, who was the managing editor of the editorial collective until 1993.[35][44]

- 1991: One of the seminal books in the history of the modern bisexual rights movement, Bi Any Other Name: Bisexual People Speak Out, an anthology edited by Loraine Hutchins and Lani Ka'ahumanu, was published.[35]

- 1991: The First International Conference on Bisexuality was held at Vrije University in Amsterdam. About 250 people attended from nine countries.[97]

- 1992: The Bisexual Connection (Minnesota) sponsored the First Annual Midwest Regional Bisexual Conference, called "BECAUSE (Bisexual Empowerment Conference: A Uniting, Supportive Experience)." [35]

- 1992: The South Florida Bisexual Network and the Florida International University's Stonewall Students Union co-sponsored the First Annual Southeast Regional Bisexual Conference. Thirty-five people from at least four southeastern states attended.[97]

- 1992-1994: Lani Ka'ahumanu served as project coordinator for an American Foundation for AIDS Research grant awarded to Lyon-Martin Women's Health Services. This was the first grant in the U.S. to target young high risk lesbian and bi women for HIV/AIDS prevention/education research. She created the "Peer Safer Sex Slut Team" with Cianna Stewart.[98]

- 1993: Sheela Lambert wrote, produced, and hosted the first television series by and for bisexuals, called Bisexual Network. It aired for 13 weeks on NYC Public Access Cable.[35]

- 1993: Ron Fox wrote the first large scale research study on bisexual identity, and established and maintained a comprehensive bibliography on bi research.[98]

- 1993: The First Annual Northwest Regional Conference was sponsored by BiNet USA, the Seattle Bisexual Women's Network, and the Seattle Bisexual Men's Union. It was held in Seattle, and fifty-five people representing Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Montana, and British Columbia attended.[35]

- 1993: The March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. As a result of lobbying by BiPOL (San Francisco), openly bisexual people held key leadership roles in local and regional organizing for the March, and for the first time bisexuals were included in the title of the March. Also, Lani Ka'ahumanu spoke at the rally, and over 1,000 people marched with the bisexual group. Coinciding with the March, BiNet USA, the Bisexual Resource Center (BRC), and the Washington, DC-based Alliance of Multicultural Bisexuals (AMBi) sponsored the Second National Conference Celebrating Bisexuality in Washington, DC. Over 600 people attended from the US and Europe, making it at the time the largest Bisexual Conference ever held.[35]

- 1993: Ron Fox authored the first large scale research study on bisexual identity, and established and maintained a comprehensive bibliography on bi research.[35]

- 1997: Dr. Fritz Klein founded the Journal of Bisexuality, the first academic, quarterly journal on bisexuality.[35]

- 1996: Angel Fabian co-organized the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention's first Gay/Bisexual Young Men of Color Summit at Gay Men of Color Conference, Miami, Florida.[98]

- 1997: At an LGBT PrideFest in Connecticut in 1997, Evelyn Mantilla came out as America's first openly bisexual state official.[59][60]

- 1998: The first bisexual pride flag, designed by Michael Page, was unveiled on Dec 5th, 1998.[109]

- 1998: BiNet USA hosted the First National Institute on Bisexuality and HIV/AIDS.[110]

- 1999: The first Celebrate Bisexuality Day was organized by Michael Page, Gigi Raven Wilbur, and Wendy Curry. It is now observed every September 23.[35]

- 1999: Dr. Fritz Klein founded the Journal of Bisexuality, the first academic, quarterly journal on bisexuality.[98]

- 1999: Marshall Miller founded the BiHealth Program at Fenway Community Health, the first funded bisexual-specific program targeting bisexual people and MSMW (men who have sex with men and women) and WSWM (women who have sex with men and women) who don't identify as bisexual. The program published "Safer sex for bisexuals and their partners" brochures.[98]

- 2000: The first anthology by bisexual people of faith, Blessed Bi Spirit (Continuum International 2000), was published. It was edited by Debra Kolodny.[111][112]

- 2002: Pete Chvany, Luigi Ferrer, James Green, Loraine Hutchins and Monica McLemore presented at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Health Summit, held in Boulder, Colorado, marking the first time bisexual people, transgender people, and intersex people were recognized as co-equal partners on the national level rather than gay and lesbian "allies" or tokens.[35]

- 2002: Robyn Ochs delivered the first bi-focused keynote during the National Association of Lesbian and Gay Addiction Professionals.[35]

- 2003: The North American Conference on Bisexuality hosted a Bi Health Summit organized by Cheryl Dobinson, Luigi Ferrer and Ron Fox, and the first Bi People of Color Summit was coordinated by Angel Fabian and Penelope Williams.[98]

- 2003: The Union for Reform Judaism retroactively applied its pro-rights policy on gays and lesbians to the bisexual and transgender communities, issuing a resolution titled, "SUPPORT FOR THE INCLUSION AND ACCEPTANCE OF THE TRANSGENDER AND BISEXUAL COMMUNITIES." [62]

- 2003: Women of Reform Judaism issued a statement describing their support for human and civil rights and the struggles of the bisexual and transgender communities, and saying, "Women of Reform Judaism accordingly: Calls for civil rights protections from all forms of discrimination against bisexual and transgender individuals; Urges that such legislation allows transgender individuals to be seen under the law as the gender by which they identify; and Calls upon sisterhoods to hold informative programs about the transgender and bisexual communities."[113]

- 2003: The Center for Sex and Culture, founded by Carol Queen and Robert Lawrence in 1994, opened its archive and sexuality research library, becoming the first public non-profit community-based space designed for adult sex education, including continuing professional education.[98]

- 2003: Loraine Hutchins and Linda Poelzl graduated from The Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality's first California Sexological Bodyworkers Certification Training as part of new movement of somatic erotic educators.[98]

- 2004: Lani Ka'ahumanu, Bobbi Keppel and the Safer Sex Sluts presented the first Safer Sex Workshop given at a joint national conference with American Society on Aging and National Association on Aging.[98]

- 2004: The "Espaço B" project ran fortnightly meetings to discuss Human Rights and bisexuality in the "Associação do Orgulho GLBT" (GLBT Pride Association), São Paulo, Brazil.[114]

- 2004: Brazil has the first politically organized participation of bisexuals in a LGBT movement event: the "II Encontro Paulista GLBT" (II GLBT Paulist Meet) in São Paulo.[114]

- 2005: The Queens Chapter of PFLAG announced the creation of the "Brenda Howard Memorial Award".[65] This was the first time a major American LGBT organization named an award after an openly bisexual person.[115]

- 2006: After a multi-year campaign, a Bisexual category was added to the Lambda Literary Awards, starting with the 2006 Awards.[116]

- 2008: Kate Brown was elected as the Oregon Secretary of State in the 2008 elections, becoming America's first openly bisexual statewide officeholder.[117][118][119]

- 2009: In October 2009, LGBT activist Amy Andre[68] was appointed as executive director of the San Francisco Pride Celebration Committee, making her San Francisco Pride's first openly bisexual woman of color executive director.[69][70]

- 2010: bi-sides,[120] a brazilian bisexual colective is founded after the first members met at the "VIII Caminhada de Lésbicas e Bissexuais" (VIII Lesbian and Bisexual Walk) in São Paulo, Brazil.[121][122]

- 2011: San Francisco's Human Rights Commission released a report on bisexual visibility, titled "Bisexual Invisibility: Impacts and Regulations." This was the first time any governmental body released such a report. The report showed, among other things, that self-identified bisexuals made up the largest single population within the LGBT community in the United States. In each study included in the report, more women identified as bisexual than lesbian, though fewer men identified as bisexual than gay.[81]

- 2012: The Bisexuality Report, the first report of its kind in the United Kingdom, was issued.[82] This report, led by Meg-John Barker (Senior Lecturer in Psychology, OU), Rebecca Jones (Lecturer, Health & Social Care, OU), Christina Richards, and Helen Bowes-Catton and Tracey Plowman (of BiUK) summarizes national and international evidence and brings out recommendations for bisexual inclusion in the future.[82]

- 2012: City Councilmember Marlene Pray joined the Doylestown, Pennsylvania council in 2012, though she resigned in 2013; she was the first openly bisexual office holder in Pennsylvania.[123][124]

- 2012: Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) became the first openly bisexual person elected to the US Congress.[125]

- 2012: On September 18, 2012, Berkeley, California became the first city in the U.S. to officially proclaim a day recognizing bisexuals.[126] The Berkeley City Council unanimously and without discussion declared September 23 as Bisexual Pride and Bi Visibility Day.[84]

- 2013: On Celebrate Bisexuality Day (the same as Bisexual Pride and Bi Visibility Day), the White House held a closed-door meeting with almost 30 bisexual advocates so they could meet with government officials and discuss issues of specific importance to the bisexual community; this was the first bi-specific event ever hosted by any White House.[85][86]

- 2013: On September 23, 2013 in the United Kingdom, government minister for Women and Equalities Jo Swinson MP issued a statement saying in part, "I welcome Bi Visibility Day [the same as Celebrate Bisexuality Day and Bisexual Pride and Bi Visibility Day, and celebrated on September 23] which helps to raise awareness of the issues that bisexual people can face and provides an opportunity to celebrate diversity and focus on the B in LGB&T."[127]

- 2013: The Bi Writers Association, which promotes bisexual writers, books, and writing, announced the winners of its first Bisexual Book Awards.[128] An awards ceremony was held at the Nuyorican Poets Café in New York City.[128]

- 2013: Daniel Kawczynski became the first MP in Britain to come out as bisexual.[129]

- 2013: BiLaw, the first American national organization of bisexual lawyers, law professors, law students, and their allies, was founded.[130][131]

- 2014: The Bisexual Resource Center, based in Boston, Massachusetts, declared March 2014 as the first Bisexual Health Awareness Month, with the theme "Bi the Way, Our Health Matters Too!"; it included the first social media campaign to address disparities in physical and mental health facing the bisexual community.[132]

- 2014: The Bisexual Research Collaborative on Health (BiRCH) was founded to search for ways to raise public awareness of bisexual health issues, as well as to continue high-level discussions of bisexual health research and plan a national (American) conference.[87][88]

- 2014: The book Bisexuality: Making the Invisible Visible in Faith Communities, the first book of its kind, was published.[89] It is by Marie Alford-Harkey and Debra W. Haffner.[89]

- 2014: After its 8th edition, held in Porto Alegre, Brazil, the "Seminário Nacional de Lésbicas e Mulheres Bissexuais - SENALE" (Annual Lesbian and Bisexual Women Seminar) [133] changed its name from SENALE to SENALESBI, giving bisexual women more visibility in the event and in the Brazilian lesbian-bisexual movement. Also, the participation, voice, and vote of bisexual and trans* women was assured from this edition on.[134][135][136]

- 2014: BiNet USA declared the seven days surrounding Celebrate Bisexuality Day to be Bi Awareness Week, also called Bisexual Awareness Week.[137][138] The week begins the Sunday before Celebrate Bisexuality Day.[139]

- 2015: Kate Brown became the first openly bisexual governor in the United States, as governor of Oregon when the old governor resigned.[91][92][93]

- 2015: Biphobia was added to the name of the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia, previously the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia.[95]

- 2015: J. Christopher Neal became the first openly bisexual New York City LGBT Pride March Grand Marshal.[140]

- 2015: The UK-based bisexual women's website Biscuit created the Purple List; the first known list of its kind, the Purple List seeks to recognize bisexuals who have contributed to fighting biphobia and increasing bisexual visibility.[141][142]

- 2015: Inga Beale, CEO of Lloyd's of London, became the first woman and the first openly bisexual person to be named number one in the OUTstanding & FT Leading LGBT executive power list.[143]

- 2016: Kate Brown was elected as governor of Oregon, and thus became the first openly bisexual person elected as a United States governor (and indeed the first openly LGBT person elected as such).[94]

Further reading

- Bi America: Myths, Truths, and Struggles of an Invisible Community, by William E. Burleson (Apr 7, 2005)

- Bi Any Other Name: Bisexual People Speak Out, an anthology edited by Loraine Hutchins and Lani Ka'ahumanu (1991)

- Bi Lives: Bisexual Women Tell Their Stories, an anthology edited by Kata Orndorff (1999)

- Bi Men's Lives: Bisexual Men Tell Their Stories, an anthology edited by Mark Zepezauer (Sep 2003)

- Bisexuality in the United States, an anthology edited by Paula Rodriguez Rust (Nov 15, 1999)

- Blessed Bi Spirit: Bisexual People of Faith, an anthology edited by Debra Kolodny (2000)

- Getting Bi: Voices of Bisexuals Around the World, second edition, an anthology edited by Robyn Ochs and Sarah Rowley (2009)

- Recognize: The Voices of Bisexual Men, an anthology edited by Robyn Ochs and H. Sharif Williams (2014)

- Lenius, S. (2001). "Bisexuals and BDSM." Journal of Bisexuality, 1(4), 69-78.

- Lenius, S. (2011). "A Reflection on "Bisexuals and BDSM: Bisexual People in a Pansexual Community"—Ten Years Later (and a Preview of the Next Sexual Revolution)." Journal of Bisexuality, 11(4), 420-425.

- Simula, B.L. (2012). "Does Bisexuality 'Undo' Gender? Gender, Sexuality, and Bisexual Behavior Among BDSM Participants." Journal of Bisexuality, 12(4), 484–506.

References

- 1 2 3 van Dolen, Hein. "Greek Homosexuality". Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ↑ Amy Richlin, The Garden of Priapus: Sexuality and Aggression in Roman Humor (Oxford University Press, 1983, 1992), p. 225.

- ↑ Catharine Edwards, "Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome," in Roman Sexualities, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ "Anne Walthall. Review of Pflugfelder, Gregory M., Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse 1600–1950. H-Japan, H-Net Reviews. May, 2000.". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1999). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-520-20909-5.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary (1995). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. p. 31

- ↑ Faure, Bernard (1998). The Red Thread: Buddhist approaches to sexuality p. 209

- ↑ Childs, Margaret (1980). "Chigo Monogatari: Love Stories or Buddhist Sermons?". Monumenta Nipponica. Sophia University. 35: 127–51. doi:10.2307/2384336.

- ↑ Pflugfelder, Gregory M. (1997). Cartographies of desire: male–male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press. pp. 39–42. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Pflugfelder, Gregory M. (1997). Cartographies of desire: male–male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ The Greenwood encyclopedia of LGBT issues worldwide, Volume 1, By Chuck Stewart, p.430; accessed through Google Books

- 1 2 3 Leupp, Gary P. (1999). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 0-520-20909-5.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1999). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-520-20909-5.

- ↑ Pflugfelder, Gregory M. (1997). Cartographies of desire: male–male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Pflugfelder, Gregory M. (1997). Cartographies of desire: male–male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Pflugfelder, Gregory M. (1997). Cartographies of desire: male–male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600–1950. University of California Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 70–78, 132–134. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 69, 134–135. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Gay love in Japan – World History of Male Love

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 34–37. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Japanese Hall

- 1 2 Mostow, Joshua S. (2003), "The gender of wakashu and the grammar of desire", in Joshua S. Mostow; Norman Bryson; Maribeth Graybill, Gender and power in the Japanese visual field, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 49–70, ISBN 0-8248-2572-1

- ↑ Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 0-520-20900-1.

- ↑ Pulitzer site Retrieved December 9, 2010

- 1 2 3 ">> arts >> Bisexuality in Film". glbtq. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Baumgardner, Jennifer (2008) [2008]. Look Both Ways: Bisexual Politics. New York, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Reprint edition. p. 48. ISBN 978-0374531089.

- ↑ Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, Table 142, p. 499

- ↑ Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Table 147, p. 651

- ↑ ">> social sciences >> Bisexuality". glbtq. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Kinsey,, A. C.; Pomeroy, W. B.; Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 "TIMELINE: THE BISEXUAL HEALTH MOVEMENT IN THE US". BiNetUSA.

- 1 2 "Channel 13/WNET Out! 2007: Women In the Movement". WNET.

- 1 2 Belonsky, Andrew (Jun 18, 2007). "The Gay Pride Issue". Queerty.

- 1 2 Dynes, Wayne R. Pride (trope), Homolexis

- ↑ ">> literature >> Bisexual Literature". glbtq. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ "BiMedia | Bisexual News & Opinion from". BiMedia.org. 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- 1 2 Donaldson, Stephen (1995). "The Bisexual Movement's Beginnings in the 70s: A Personal Retrospective". In Tucker, Naomi. Bisexual Politics: Theories, Queries, & Visions. New York: Harrington Park Press. pp. 31–45. ISBN 1-56023-869-0.

- 1 2 Highleyman, Liz (2003-07-11). "PAST Out: What is the history of the bisexual movement?". LETTERS From CAMP Rehoboth. 13 (8). Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- 1 2 Martin, Robert (1972-08-02). "Quakers 'come out' at conference". The Advocate (91): 8.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bisexual network celebrates 25 years". www.ebar.com. 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "BiNet USA". BiNet USA. 1990-06-23. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- 1 2 3 "First Person Biography of a Bisexual US Army Veteran". GLAAD. 2009-09-23. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- ↑ "2010 Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repealed! A look back at Bi one veteran's story – BiNet USA". Binetusa.org. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- 1 2 "The UK national get-together for bisexuals, allies and friends". BiCon. 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- 1 2 http://www.lanikaahumanu.com/OUT%20OUTRAGED.pdf

- 1 2 Kiritsy, Laura (May 31, 2007). "Happy Anniversary, Barney Frank!". EDGE.

- 1 2 Carlos Santoscoy (September 20, 2009). "Barney Frank's 'Left-Handed Gay Jew' No Tell-All". On Top Magazine. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "All About BiNet USA including the Fine Print". BiNet USA. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- 1 2 Summers, Claude J. (2009-10-20). "BiNet USA". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. glbtq, Inc.

- ↑ "Directed by Desire: Collected Poems". Copper Canyon Press. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ "2005 Lambda Literary Awards Recipients". Lambda Literary Foundation. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ Garber, Marjorie B. (2000). Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life. New York: Routledge. p. 249. ISBN 0-415-92661-0.

- 1 2 ">> arts >> Bisexuality in Film". glbtq. 2004-12-28. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Sexuality Questions to the Kinsey Institute". The Kinsey Institute. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- 1 2 Siadate, Nazly (2012-08-23). "America's Six Out Bisexual Elected State Officials". Advocate.com. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- 1 2 Matt & Andrej Koymasky (August 4, 2004). "Famous GLTB - Evelyn C. Mantilla".

- ↑ "Counseling and Wellness Services - Safezone Symbols". Wright.edu. 1998-12-05. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- 1 2 "Support for the Inclusion and Acceptance of the Transgender and Bisexual Communities".

- ↑ "New York Times Suggests Bisexuals Are 'Lying'". Fair.org. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ "Male Bisexuals, Ridiculed by Gays and Straights, Find Comfort in New Study - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. 2011-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- 1 2 "The PFLAG Queens Chapter Names New Award for Bisexual Activist Brenda Howard". Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ "Bi/Pan March Contingent".

- ↑ Maria, October 15, 2009. "My Experience at the National Equality March", Bi Social Network

- 1 2 "Amy Andre to head San Francisco Pride".

- 1 2

- ↑ Leonard Sax. "Why Are So Many Girls Lesbian or Bisexual?". Sussex Directories. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ↑ Carey, Benedict (July 5, 2005). "Straight, Gay or Lying? Bisexuality Revisited". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ↑ Alan, Patrick. "Walking Bi | Queer". Portland Mercury. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ "Kate Brown". OutHistory. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Walsh, Edward (2008-11-05). "Democrats sweep to capture statewide jobs". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Bajko, Matthew S. "The Bay Area Reporter Online | Political Notebook: Bisexual, lesbian politicians stump in SF". Ebar.com. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ ""Don't Ask, Don't Tell" | National Black Justice Coalition". Nbjc.org. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Join the discussion: Click to view comments, add yours. "President Obama signs repeal of 'don't ask, don't tell' policy - Tampa Bay Times". Tampabay.com. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Bumiller, Elisabeth (2011-07-22). "Obama Ends 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' Policy". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Official Repeal of Gay Ban Causing Few Waves in Military". Fox News. 2011-09-20.

- 1 2 3 Diane Anderson-Minshall (September 23, 2011). "The Biggest Bisexual News Stories of 2011".

- 1 2 3 4 Amandine Scherrer (2012-02-14). "The Bisexuality Report is now available - News - Centre for Citizenship, Identities and Governance (CCIG) - Open University". Open.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- ↑ "The Bi Report Story - So Far". Bi Community News. BCN. 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2015-01-18.

- 1 2 3 "Berkeley Lawmakers Recognize Bisexual Pride Day". Mercury News. Associated Press. September 18, 2012. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

- 1 2 "In Historic First, Bi Activists Gather at White House". http://www.bilerico.com. September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013. External link in

|work=(help) - 1 2 "White House to hold closed-door session on bisexual issues next month". http://www.washingtonpost.com/. August 22, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013. External link in

|work=(help) - 1 2 "Groundbreaking bisexual research collaborative formed". GLAAD. 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- 1 2 Materville Studios - Host of Windy City Times. "Bisexual Research Collaborative On Health formed - 978 - Gay Lesbian Bi Trans News Archive - Windy City Times". Windycitymediagroup.com. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Cruz, Eliel (2014-06-21). "Organization is Helping Bisexuals Be Happily Embraced By God". Advocate.com. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ↑ "Democrat Kyrsten Sinema beats GOP's Vernon Parker in Arizona's 9th Congressional District". Star Tribune. November 12, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- 1 2 "Meet America's First Openly Bisexual Governor". MSN. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Live updates: Kate Brown becomes Oregon governor". OregonLive.com. Retrieved 2015-02-18.

- 1 2 "Gov. John Kitzhaber Announces His Resignation". Willamette Week. February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- 1 2 Helena Horton (2016-09-08). "People are celebrating women who made history on US Election night in response to Donald Trump win". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- 1 2 "IDAHOT | Metropolitan Community Churches". Mccchurch.org. Retrieved 2015-05-15.

- ↑ (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20140315172313/http://www.gpascotland.com/Reference_files/GPA%20Gay%20Events%20Timeline.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2014. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 BiNet USA

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 BiNet USA

- ↑ "BiMedia | Bisexual News & Opinion from". BiMedia.org. 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ "Stances of Faiths on LGBT Issues: Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) | Resources | Human Rights Campaign". Hrc.org. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ Bisexual and Gay Husbands: Their Stories, Their Words - Fritz Klein, Thomas R Schwartz - Google Books

- ↑ "A History of the LGBTQA Movement". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Coleman, Edmond J (1987-09-10). Integrated Identity for Gay Men and Lesbians: Psychotherapeutic Approaches for Emotional Well-Being. Psychology Press. pp. 13–. ISBN 9780866566384. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ The Bad Subjects Production Team (1997-11-01). Bad Subjects: Political Education for Everyday Life. NYU Press. pp. 108–. ISBN 9780814757932. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ Bancroft, John (2009). Human Sexuality And It Problems. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 262–. ISBN 9780443051616. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ Klein, Fritz; Barry Sepekoff; Timothy J. Wolf (1985). "Sexual Orientation:". Journal of Homosexuality. 11 (1–2): 35–49. doi:10.1300/J082v11n01_04. ISSN 0091-8369.

- ↑ BRC Welcome

- ↑ New York Area Bisexual Network: A Brief History of NYC's Bisexual Community

- ↑ "Counseling and Wellness Services - Safezone Symbols". Wright.edu. 1998-12-05. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ "BiNet USA". BiNet USA. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America: Women and religion ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "Blessed Bi Spirit: Bisexual People of Faith: Debra Kolodny: 9780826412317: Amazon.com: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20130516091332/http://www.wrj.org/Advocacy/ResolutionsStatements/Resolutions2003/2003TransgenderandBisexualRights.aspx

- 1 2 Postado por Espaço B. "Espaço B: Bissexualidade em movimento (agosto de 2004)". Blog-espaco-b.blogspot.com.ar. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ↑ Robyn Ochs receives the 2011 PFLAG Queens Brenda Howard Award

- ↑ The Lamda Literary Awards 2010 Are on Their Way - Curve Magazine - Web Articles 2010 - USA

- ↑ Walsh, Edward (5 November 2008). "Democrats sweep to capture statewide jobs". The Oregonian. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ↑ Ferguson, Courtney. "Walking Bi | Queer". Portland Mercury. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Bajko, Matthew S. (2007-11-22). "The Bay Area Reporter Online | Political Notebook: Bisexual, lesbian politicians stump in SF". Ebar.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Bissexuais reclamam que são discriminados por héteros e gays" (in Portuguese). .folha.uol.com.br. 2011-09-19. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ "Bissexual começa movimento por nova representação na sociedade brasileira" (in Portuguese). YouTube. 2010-06-05. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ "Primeiros Passosbi-sides". bi-sides. 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ↑ "Marlene Pray Becomes First Openly Bisexual Office Holder In PA - Amplify". Amplifyyourvoice.org. 2012-01-04. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Marlene Pray resigns from Doylestown Council - phillyburbs.com: Doylestown". phillyburbs.com. 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Kyrsten Sinema Becomes First Openly Bisexual Member of Congress". ABC News. 12 November 2012.

- ↑ "Berkeley becomes first US city to declare Bisexual Pride Day, support 'marginalized' group". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "UK equalities minister welcomes Bi Visibility Day". http://www.bimedia.org/. 23 September 2013. External link in

|work=(help) - 1 2 Heffernan, Dani (2013-06-06). "Bi Writers Association announces recipients of Bisexual Book Awards". GLAAD. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Legge, James (30 June 2013). "Tory MP Daniel Kawczynski comes out as bisexual". The Independent. London.