History of hospitals

The history of hospitals has stretched over 2500 years.

Early examples

In ancient cultures, religion and medicine were linked. The earliest documented institutions aiming to provide cures were ancient Egyptian temples. In ancient Greece, temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Ancient Greek: Ἀσκληπιεῖα, sing. Asclepieion, Ἀσκληπιεῖον), functioned as centres of medical advice, prognosis, and healing.[1] At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as enkoimesis (ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery.[2] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[3] In the Asclepieion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BCE preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there. Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium.[2] The worship of Asclepius was adopted by the Romans. Under his Roman name Æsculapius, he was provided with a temple (291 BCE) on an island in the Tiber in Rome, where similar rites were performed.[4]

Institutions created specifically to care for the ill also appeared early in India. Fa Xian, a Chinese Buddhist monk who travelled across India ca. 400 CE, recorded in his travelogue [5] that

The heads of the Vaishya [merchant] families in them [all the kingdoms of north India] establish in the cities houses for dispensing charity and medicine. All the poor and destitute in the country, orphans, widowers, and childless men, maimed people and cripples, and all who are diseased, go to those houses, and are provided with every kind of help, and doctors examine their diseases. They get the food and medicines which their cases require, and are made to feel at ease; and when they are better, they go away of themselves.

The earliest surviving encyclopaedia of medicine in Sanskrit is the Carakasamhita (Compendium of Caraka). This text, which describes the building of a hospital is dated by Dominik Wujastyk of the University College London from the period between 100 BCE and 150 CE.[6] The description by Fa Xian is one of the earliest accounts of a civic hospital system anywhere in the world and, coupled with Caraka’s description of how a clinic should be equipped, suggests that India may have been the first part of the world to have evolved an organized cosmopolitan system of institutionally-based medical provision.[6]

King Ashoka is wrongly said by many secondary sources to have founded at hospitals in ca. 230 BCE[7]

According to the Mahavamsa, the ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty, written in the sixth century CE, King Pandukabhaya of Sri Lanka (reigned 437 BCE to 367 BCE) had lying-in-homes and hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various parts of the country. This is the earliest documentary evidence we have of institutions specifically dedicated to the care of the sick anywhere in the world.[8][9] Mihintale Hospital is the oldest in the world.[10]

Roman Empire

The Romans constructed buildings called valetudinaria for the care of sick slaves, gladiators, and soldiers around 100 BCE, and many were identified by later archeology. While their existence is considered proven, there is some doubt as to whether they were as widespread as was once thought, as many were identified only according to the layout of building remains, and not by means of surviving records or finds of medical tools.[11]

The declaration of Christianity as an accepted religion in the Roman Empire drove an expansion of the provision of care. Following First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE construction of a hospital in every cathedral town was begun. Among the earliest were those built by the physician Saint Sampson in Constantinople and by Basil, bishop of Caesarea in modern-day Turkey. Called the "Basilias", the latter resembled a city and included housing for doctors and nurses and separate buildings for various classes of patients.[12] There was a separate section for lepers.[13] Some hospitals maintained libraries and training programs, and doctors compiled their medical and pharmacological studies in manuscripts. Thus in-patient medical care in the sense of what we today consider a hospital, was an invention driven by Christian mercy and Byzantine innovation.[14] Byzantine hospital staff included the Chief Physician (archiatroi), professional nurses (hypourgoi) and the orderlies (hyperetai). By the twelfth century, Constantinople had two well-organized hospitals, staffed by doctors who were both male and female. Facilities included systematic treatment procedures and specialized wards for various diseases.[15]

A hospital and medical training centre also existed at Gundeshapur. The city of Gundeshapur was founded in 271 CE by the Sassanid king Shapur I. It was one of the major cities in Khuzestan province of the Persian empire in what is today Iran. A large percentage of the population were Syriacs, most of whom were Christians. Under the rule of Khusraw I, refuge was granted to Greek Nestorian Christian philosophers including the scholars of the Persian School of Edessa (Urfa)(also called the Academy of Athens), a Christian theological and medical university. These scholars made their way to Gundeshapur in 529 following the closing of the academy by Emperor Justinian. They were engaged in medical sciences and initiated the first translation projects of medical texts.[16] The arrival of these medical practitioners from Edessa marks the beginning of the hospital and medical centre at Gundeshapur.[17] It included a medical school and hospital (bimaristan), a pharmacology laboratory, a translation house, a library and an observatory.[18] Indian doctors also contributed to the school at Gundeshapur, most notably the medical researcher Mankah. Later after Islamic invasion, the writings of Mankah and of the Indian doctor Sustura were translated into Arabic at Baghdad.[19]

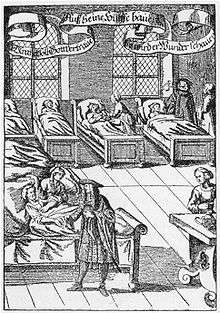

Medieval Europe

Medieval hospitals in Europe followed a similar pattern to the Byzantine. They were religious communities, with care provided by monks and nuns. (An old French term for hospital is hôtel-Dieu, "hostel of God.") Some were attached to monasteries; others were independent and had their own endowments, usually of property, which provided income for their support. Some hospitals were multi-functional while others were founded for specific purposes such as leper hospitals, or as refuges for the poor, or for pilgrims: not all cared for the sick. The first Spanish hospital, founded by the Catholic Visigoth bishop Masona in 580 CE at Mérida, was a xenodochium designed as an inn for travellers (mostly pilgrims to the shrine of Eulalia of Mérida) as well as a hospital for citizens and local farmers. The hospital's endowment consisted of farms to feed its patients and guests. From the account given by Paul the Deacon we learn that this hospital was supplied with physicians and nurses, whose mission included the care the sick wherever they were found, "slave or free, Christian or Jew." [20]

During the late 8th and early 9th centuries, Emperor Charlemagne decreed that those hospitals that had been well conducted before his time and had fallen into decay should be restored in accordance with the needs of the time.[21] He further ordered that a hospital should be attached to each cathedral and monastery.[21]

During the 10th century, the monasteries became a dominant factor in hospital work. The famous Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, set the example which was widely imitated throughout France and Germany. Besides its infirmary for the religious, each monastery had a hospital in which externs were cared for. These were in charge of the eleemosynarius, whose duties, carefully prescribed by the rule, included every sort of service that the visitor or patient could require.

As the eleemosynarius was obliged to seek out the sick and needy in the neighborhood, each monastery became a center for the relief of suffering. Among the monasteries notable in this respect were those of the Benedictines at Corbie in Picardy, Hirschau, Braunweiler, Deutz, Ilsenburg, Liesborn, Pram, and Fulda; those of the Cistercians at Arnsberg, Baumgarten, Eberbach, Himmenrode, Herrnalb, Volkenrode, and Walkenried.

No less efficient was the work done by the diocesan clergy in accordance with the disciplinary enactments of the councils of Aachen (817, 836), which prescribed that a hospital should be maintained in connection with each collegiate church. The canons were obliged to contribute towards the support of the hospital, and one of their number had charge of the inmates. As these hospitals were located in cities, more numerous demands were made upon them than upon those attached to the monasteries. In this movement the bishop naturally took the lead, hence the hospitals founded by Heribert (d. 1021) in Cologne, Godard (d. 1038) in Hildesheim, Conrad (d. 975) in Constance, and Ulrich (d. 973) in Augsburg. But similar provision was made by the other churches; thus at Trier the hospitals of Saint Maximin, Saint Matthew, Saint Simeon, and Saint James took their names from the churches to which they were attached. During the period 1207–1577 no less than one hundred and fifty-five hospitals were founded in Germany.[22]

The Ospedale Maggiore, traditionally named Ca' Granda (i.e. Big House), in Milan, northern Italy, was constructed to house one of the first community hospitals, the largest such undertaking of the fifteenth century. Commissioned by Francesco Sforza in 1456 and designed by Antonio Filarete it is among the first examples of Renaissance architecture in Lombardy.

The Normans brought their hospital system along when they conquered England in 1066. By merging with traditional land-tenure and customs, the new charitable houses became popular and were distinct from both English monasteries and French hospitals. They dispensed alms and some medicine, and were generously endowed by the nobility and gentry who counted on them for spiritual rewards after death.[23]

Medieval Islamic world

The first, most well known physicians in the Medieval Islamic world were polymaths Ibn Sina, (Greek: Avicenna) and Al Rhazi (Greek: Rhazes) during the 7th century.[24] The first prominent Islamic hospital was founded in Damascus, Syria in around 707 CE.[25] However most agree that the establishment at Baghdad was the most influential. The public hospital in Baghdad was opened during the Abbasid Caliphate of Harun al-Rashid in the 8th century.[26] The bimaristan (medical school) and bayt al-hikmah (house of wisdom) were founded by Caliph Harun al-Rashid.[27] The most earliest, and prominent figure of the House of Wisdom was Al-Kindi, known as "the Philosopher of the Arabs".[28] "Bimaristan" is a compound of “bimar” (sick or ill) and “stan” (place). In the medieval Islamic world, the word "bimaristan" referred to a hospital establishment where the ill were welcomed, cared for and treated by qualified staff.

In the ninth and tenth centuries the hospital in Baghdad employed twenty-five staff physicians and had separate wards for different conditions.[29] The Al-Qairawan hospital and mosque, in Tunisia, were built under the Aghlabid rule in 830 CE and was simple, but adequately equipped with halls organized into waiting rooms, a mosque, and a special bath. The first hospital in Egypt was opened in 872 CE and thereafter public hospitals sprang up all over the empire from Islamic Spain and the Maghrib to Persia. The first Islamic psychiatric hospital was built in Baghdad in 705. Many other Islamic hospitals also often had their own wards dedicated to mental health.[30]

In contrast to medieval Europe, medical schools under Islam did not have faculties; only a few of the most prominent physicians had positions in hospitals. There were no professional guilds, systematic examinations or diplomas. Huff says, "Lacking diplomas, degrees, a standard curriculum, and an organized body of professionals to enforce minimum standards – it is not surprising to learn that charlatanism was widespread."[31]

Early modern Europe

In Europe the medieval concept of Christian care evolved during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into a secular one.[32] Theology was the problem. The Protestant reformers rejected the Catholic belief that rich men could gain God's grace through good works – and escape purgatory – by providing endowments to charitable institutions, and that the patients themselves could gain grace through their suffering.[33]

After the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540 by King Henry VIII the church abruptly ceased to be the supporter of hospitals, and only by direct petition from the citizens of London, were the hospitals St Bartholomew's, St Thomas's and St Mary of Bethlehem's (Bedlam) endowed directly by the crown; this was the first instance of secular support being provided for medical institutions.[34] It was at St. Bartholomew that William Harvey conducted his research on the circulatory system in the 17th century, Percivall Pott and John Abernethy developed important principles of modern surgery in the 18th century, and Mrs. Bedford Fenwich worked to advance the nursing profession in the late 19th century.[35]

There were 28 asylums in Sweden at the start of the Reformation. Gustav Vasa removed them from church control and expelled the monks and nuns, but allowed the asylums to keep their properties and to continue their activities under the auspices of local government.[36]

In much of Europe town governments operated small Holy Spirit hospitals, which had been founded in the 13th and 14th centuries. They distributed free food and clothing to the poor, provided for homeless women and children, and gave some medical and nursing care. Many were raided and closed during the Thirty Years War (1618–48), which ravaged the towns and villages of Germany and neighboring areas for three decades.

Meanwhile, in Catholic lands such as France, rich families continued to fund convents and monasteries that provided free health services to the poor. French practices were influenced by a charitable imperative which considered care of the poor and the sick to be a necessary part of Catholic practice. The nursing nuns had little faith in the power of physicians and their medicines alone to cure the sick; more important was providing psychological and physical comfort, nourishment, rest, cleanliness and especially prayer.[37]

In Protestant areas the emphasis was on scientific rather than religious aspects of patient care, and this helped develop a view of nursing as a profession rather than a vocation.[38] There was little hospital development by the main Protestant churches after 1530.[39] Some smaller groups such as the Moravians and the Pietists at Halle gave a role for hospitals, especially in missionary work.[40]

Enlightenment

In the 18th century, under the influence of the Age of Enlightenment, the modern hospital began to appear, serving only medical needs and staffed with trained physicians and surgeons. The nurses were untrained workers. The goal was to use modern methods to cure patients. They provided more narrow medical services, and were founded by the secular authorities. A clearer distinction emerged between medicine and poor relief. Within the hospitals, acute cases were increasingly treated alone, and separate departments were set up for different categories of patient.

The voluntary hospital movement began in the early 18th century, with hospitals being founded in London by the 1710s and 20s, including Westminster Hospital (1719) promoted by the private bank C. Hoare & Co and Guy's Hospital (1724) funded from the bequest of the wealthy merchant, Thomas Guy. Other hospitals sprang up in London and other British cities over the century, many paid for by private subscriptions. St. Bartholomew's in London was rebuilt in 1730, and the London Hospital opened in 1752.

These hospitals represented a turning point in the function of the institution; they began to evolve from being basic places of care for the sick to becoming centres of medical innovation and discovery and the principle place for the education and training of prospective practitioners. Some of the era's greatest surgeons and doctors worked and passed on their knowledge at the hospitals.[41] They also changed from being mere homes of refuge to being complex institutions for the provision of medicine and care for sick. The Charité was founded in Berlin in 1710 by King Frederick I of Prussia as a response to an outbreak of plague.

The concept of voluntary hospitals also spread to Colonial America; the Pennsylvania Hospital opened in 1752, New York Hospital in 1771, and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1811. When the Vienna General Hospital opened in 1784 (instantly becoming the world's largest hospital), physicians acquired a new facility that gradually developed into one of the most important research centres.[42]

Another Enlightenment era charitable innovation was the dispensary; these would issue the poor with medicines free of charge. The London Dispensary opened its doors in 1696 as the first such clinic in the British Empire. The idea was slow to catch on until the 1770s, when many such organizations began to appear, including the Public Dispensary of Edinburgh (1776), the Metropolitan Dispensary and Charitable Fund (1779) and the Finsbury Dispensary (1780). Dispensaries were also opened in New York 1771, Philadelphia 1786, and Boston 1796.[43]

Across Europe medical schools still relied primarily on lectures and readings. In the final year, students would have limited clinical experience by following the professor through the wards. Laboratory work was uncommon, and dissections were rarely done because of legal restrictions on cadavers. Most schools were small, and only Edinburgh, Scotland, with 11,000 alumni, produced large numbers of graduates.[44][45]

Spanish Americas

The first hospital founded in the Americas was the Hospital San Nicolás de Bari [Calle Hostos] in Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional Dominican Republic. Fray Nicolás de Ovando, Spanish governor and colonial administrator from 1502–1509, authorized its construction on December 29, 1503. This hospital apparently incorporated a church. The first phase of its construction was completed in 1519, and it was rebuilt in 1552.[46] Abandoned in the mid-18th century, the hospital now lies in ruins near the Cathedral in Santo Domingo.

Conquistador Hernán Cortés founded the two earliest hospitals in North America: the Immaculate Conception Hospital and the Saint Lazarus Hospital. The oldest was the Immaculate Conception, now the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno in Mexico City, founded in 1524 to care for the poor.[46]

Modern hospitals

English physician Thomas Percival (1740–1804) wrote a comprehensive system of medical conduct, 'Medical Ethics, or a Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and Surgeons (1803) that set the standard for many textbooks.[47]

In the mid 19th century, hospitals and the medical profession became more professionalized, with a reorganization of hospital management along more bureaucratic and administrative lines. The Apothecaries Act 1815 made it compulsory for medical students to practice for at least half a year at a hospital as part of their training.[48] An example of this professionalization was the Charing Cross Hospital, set up in 1818 as the 'West London Infirmary and Dispensary' from funds provided by Dr. Benjamin Golding. By 1821 it was treating nearly 10,000 patients a year, and it was relocated to larger quarters near Charing Cross in the heart of London. Its Charing Cross Hospital Medical School opened in 1822. It expanded several times and 1866 added a professional nursing staff.[49]

Florence Nightingale pioneered the modern profession of nursing during the Crimean War when she set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. The first official nurses’ training programme, the Nightingale School for Nurses, was opened in 1860, with the mission of training nurses to work in hospitals, to work with the poor and to teach.[50]

Nightingale was instrumental in reforming the nature of the hospital, by improving sanitation standards and changing the image of the hospital from a place the sick would go to die, to an institution devoted to recuperation and healing. She also emphasized the importance of statistical measurement for determining the success rate of a given intervention and pushed for administrative reform at hospitals.[51]

During the middle of the 19th century, the Second Viennese Medical School emerged with the contributions of physicians such as Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky, Josef Škoda, Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra, and Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis. Basic medical science expanded and specialization advanced. Furthermore, the first dermatology, eye, as well as ear, nose, and throat clinics in the world were founded in Vienna.[52]

By the late 19th century, the modern hospital was beginning to take shape with a proliferation of a variety of public and private hospital systems. By the 1870s, hospitals had more than tripled their original average intake of 3,00 patients. In continental Europe the new hospitals generally were built and run from public funds. Nursing was professionalized in France by the turn of the 20th century. At that time, the country's 1,500 hospitals were operated by 15,000 nuns representing over 200 religious orders. Government policy after 1900 was to secularize public institutions, and diminish the role the Catholic Church. This political goal came in conflict with the need to maintain better quality of medical care in antiquated facilities. New government-operated nursing schools turned out nonreligous nurses who were slated for supervisory roles. During the First World War, an outpouring of patriotic volunteers brought large numbers of untrained middle-class women into the military hospitals. They left when the war ended but the long-term effect was to heighten the prestige of nursing. In 1922 the government issued a national diploma for nursing.[53]

In the U.S., the number of hospitals reached 4400 in 1910, when they provided 420,000 beds.[54] These were operated by city, state and federal agencies, by churches, by stand-alone non-profits, and by for-profit enterprises. All the major denominations built hospitals; the 541 Catholic ones (in 1915) were staffed primarily by unpaid nuns. The others sometimes had a small cadre of deaconesses as staff.[55] Non-profit hospitals were supplemented by large public hospitals in major cities and research hospitals often affiliated with a medical school. The largest public hospital system in America is the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which includes Bellevue Hospital, the oldest U.S. hospital, affiliated with New York University Medical School.[56]

The National Health Service, the principal provider of health care in Britain, was founded in 1948, and took control of nearly all the hospitals.[57]

Church-sponsored hospitals and nurses

Protestants

The Protestant churches reentered the health field in the 19th century, especially with the establishment of orders of women, called deaconesses who dedicated themselves to nursing services. This movement began in Germany in 1836 when Theodor Fliedner and his wife opened the first deaconess motherhouse in Kaiserswerth on the Rhine. It became a model, and within half a century there were over 5,000 deaconesses in Europe. The Church of England named its first deaconess in 1862. The North London Deaconess Institution trained deaconesses for other dioceses and some served overseas.[58]

William Passavant in 1849 brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, in the United States, after visiting Kaiserswerth. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary (now Passavant Hospital).[59]

The American Methodists made medical services a priority from the 1850s. They began opening charitable institutions such as orphanages and old people's homes. In the 1880s, Methodists began opening hospitals in the United States, which served people of all religious backgrounds beliefs. By 1895, 13 hospitals were in operation in major cities.[60]

Catholics

In Quebec, Catholics operated hospitals continuously from the 1640s; they attracted nuns from the provincial elite. Jeanne Mance (1606–73) founded Montreal's city's first hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, in 1645. In 1657 she recruited three sisters of the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph, and continued to direct operations of the hospital. The project, begun by the niece of Cardinal de Richelieu was granted a royal charter by King Louis XIII and staffed by a colonial physician, Robert Giffard de Moncel.[61] The General Hospital in Quebec City opened in 1692. They often handled malaria, dysentery, and respiratory sickness.[62]

In the 1840s–1880s era, Catholics in Philadelphia founded two hospitals, for the Irish and German Catholics. They depended on revenues from the paying sick, and became important health and welfare institutions in the Catholic community.[63] By 1900 the Catholics had set up hospitals in most major cities. In New York the Dominicans, Franciscans, Sisters of Charity, and other orders set up hospitals to care primarily for their own ethnic group. By the 1920s they were serving everyone in the neighborhood.[64] In smaller cities too the Catholics set up hospitals, such as St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, Montana. The Sisters of Providence opened it in 1873. It was in part funded by the county contract to care for the poor, and also operated a day school and a boarding school. The nuns provided nursing care especially for infectious diseases and traumatic injuries among the young, heavily male clientele. They also proselytized the patients to attract converts and restore lapsed Catholics back into the Church. They built a larger hospital in 1890.[65] Catholic hospitals were largely staffed by Catholic orders of nuns, and nursing students, until the population of nuns dropped sharply after the 1960s. The Catholic Hospital Association formed in 1915.[66][67]

See also

References

- ↑ Risse, G.B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56 Books.Google.com

- 1 2 Askitopoulou, H., Konsolaki, E., Ramoutsaki, I., Anastassaki, E. Surgical cures by sleep induction as the Asclepieion of Epidaurus. The history of anaesthesia: proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium, by José Carlos Diz, Avelino Franco, Douglas R. Bacon, J. Rupreht, Julián Alvarez. Elsevier Science B.V., International Congress Series 1242(2002), p.11-17. Books.Google.com

- ↑ Risse, G.B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56 Books.Google.com

- ↑ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopaedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), pp. 134–35.

- ↑ Legge, James, A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fâ-Hien of his Travels in India and Ceylon (399–414 CE) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline, 1965

- 1 2 The Nurses should be able to Sing and Play Instruments - Wujastyk, Dominik; University College London.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Medical History - McGrew, Roderick E. (Macmillan 1985), p. 135.

- ↑ Prof. Arjuna Aluvihare, "Rohal Kramaya Lovata Dhayadha Kale Sri Lankikayo" Vidhusara Science Magazine, Nov. 1993.

- ↑ Resource Mobilization in Sri Lanka's Health Sector - Rannan-Eliya, Ravi P. & De Mel, Nishan, Harvard School of Public Health & Health Policy Programme, Institute of Policy Studies, February 1997, p. 19. Accessed 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Heinz E Müller-Dietz, Historia Hospitalium (1975).

- ↑ The Roman military Valetudinaria: fact or fiction – Baker, Patricia Anne, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunday 20 December 1998

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia – (2009)

- ↑ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopedia of Medical History (1985), p. 135.

- ↑ James Edward McClellan and Harold Dorn, Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), pp. 99, 101.

- ↑ Byzantine medicine

- ↑ Mehmet Mahfuz Söylemez, "The Jundishapur School: Its History, Structure, and Functions,", The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 22:2 p. 3

- ↑ Gail Marlow Taylor, The Physicians of Jundishapur, (University of California, Irvine), p. 7

- ↑ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p. 7

- ↑ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p. 3

- ↑ See Florez, "Espana Sagrada", XIII, 539; Heusinger, "Ein Beitrag", etc. in "Janus", 1846, I.

- 1 2 Capitulary Duplex, 803, chapter iii

- ↑ Virchow in "Gesch. Abhandl.", II

- ↑ Sethina Watson, "The Origins of the English Hospital," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society , Sixth Series (2006) 16:75–94 in JSTOR

- ↑ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), pp. 234–35.

- ↑ Guenter B. Risse, Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals,(Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 125

- ↑ Sir Glubb, John Bagot (1969), A Short History of the Arab Peoples, retrieved 2008-01-25

- ↑ Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 1973, p. 204 Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol. 1, A-K, Index, 2006, p. 304

- ↑ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2006). Islamic philosophy from its origin to the present : philosophy in the land of prophecy. State Univ. of New York Press. pp. 137–38. ISBN 0-7914-6799-6.

- ↑ Husain F. Nagamia, Islamic Medicine History and Current Practice, (2003), p. 24.

- ↑ Medicine And Health, "Rise and Spread of Islam 622–1500: Science, Technology, Health", World Eras, Thomson Gale.

- ↑ Toby E. Huff (2003). The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China and the West. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-521-52994-5.

- ↑ Andrew Cunningham; Ole Peter Grell (2002). Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe 1500–1700. Routledge. pp. 130–33.

- ↑ C. Scott Dixon; et al. (2009). Living With Religious Diversity in Early-Modern Europe. Ashgate. pp. 128–30.

- ↑ Keir Waddington (2003). Medical Education at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, 1123–1995. Boydell & Brewer. p. 18.

- ↑ James O. Robinson, "The Royal and Ancient Hospital of St Bartholomew (Founded 1123)," Journal of Medical Biography (1993) 1:1 pp. 23–30

- ↑ Virpi Mäkinen (2006). Lutheran Reformation And the Law. BRILL. pp. 227–29.

- ↑ Olwen Hufton, The Prospect before Her. A History of Women in Western Europe, 1500–1800 (1995), pp 382–84.

- ↑ Tim McHugh, "Expanding Women’s Rural Medical Work in Early Modern Brittany: The Daughters of the Holy Spirit," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences (2012) 67#3 pp 428-456. in project MJUSE

- ↑ Johann Jakob Herzog; Philip Schaff (1911). The new Schaff-Herzog encyclopedia of religious knowledge. Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 468–9.

- ↑ Christopher M. Clark (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise And Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Harvard U.P. p. 128.

- ↑ Reinarz, Jonathan. "Corpus Curricula: Medical Education and the Voluntary Hospital Movement". Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), p. 139.

- ↑ Michael Marks Davis; Andrew Robert Warner (1918). Dispensaries, Their Management and Development: A Book for Administrators, Public Health Workers, and All Interested in Better Medical Service for the People. MacMillan. pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Thomas H. Broman, "The Medical Sciences," in Roy Porter, ed, The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 4: 18th-century Science (2003) pp. 465–68

- ↑ Lisa Rosner, Medical Education in the Age of Improvement: Edinburgh Students and Apprentices 1760–1826 (1991)

- 1 2 Alfredo De Micheli, En torno a la evolución de los hospitales, Gaceta Médica de México, vol. 141, no. 1 (2005), p. 59.

- ↑ Ivan Waddington, "The Development of Medical Ethics – A Sociological Analysis," Medical History (1975) 19:1 pp. 36–51

- ↑ Porter, Roy (1999) [1997]. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 316–17. ISBN 978-0-393-31980-4.

- ↑ R.J. Minney, The Two Pillars Of Charing Cross: The Story of a Famous Hospital (1967)

- ↑ Kathy Neeb (2006). Fundamentals of Mental Health Nursing. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

- ↑ Nightingale, Florence (August 1999). Florence Nightingale: Measuring Hospital Care Outcomes. ISBN 0-86688-559-5. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Erna Lesky, The Vienna Medical School of the 19th Century (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976)

- ↑ Katrin Schultheiss, Bodies and Souls: politics and the professionalization of nursing in France, 1880–1922 (2001), pp. 3–11, 99, 116

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) p. 78

- ↑ Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) p. 76

- ↑ Barbra Mann Wall, American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (Rutgers University Press; 2011)

- ↑ Martin Gorsky, "The British National Health Service 1948–2008: A Review of the Historiography," Social History of Medicine, Dec 2008, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp. 437–60

- ↑ Henrietta Blackmore. The beginning of women's ministry: the revival of the deaconess in the nineteenth-century Church of England. Boydell Press. p. 131.

- ↑ See Christ Lutheran Church of Baden

- ↑ Wade Crawford Berkeley, History of Methodist Missions: The Methodist Episcopal Church 1845–1939 (1957) pp. 82, 192–93, 482

- ↑ Joanna Emery, "Angel of the Colony," Beaver (Aug/Sep 2006) 86:4 pp. 37–41. online

- ↑ François Rousseau, "Hôpital et Société en Nouvelle-France: L'Hôtel-Dieu de Québec À la Fin du XVIIie Siècle," Revue d'histoire de L'Amerique francaise (1977) 31:1 pp. 29–47

- ↑ Gail Farr Casterline, "St. Joseph's and St. Mary's: The Origins of Catholic Hospitals in Philadelphia," Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography (1984) 108:3 pp. 289–314

- ↑ Bernadette McCauley, "'Sublime Anomalies': Women Religious and Roman Catholic Hospitals in New York City, 1850–1920," Journal of the History of Medicine & Allied Sciences (1997) 52:3 pp. 289–309.

- ↑ Todd L. Savitt, and Janice Willms, "Sisters' Hospital: The Sisters of Providence and St. Patrick Hospital, Missoula, Montana, 1873–1890," Montana: The Magazine of Western History (2003) 53:1 pp. 28–43.

- ↑ Barbra Mann Wall, Unlikely Entrepreneurs: Catholic Sisters and the Hospital Marketplace, 1865–1925 (2005)

- ↑ Barbra Mann Wall, American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (Rutgers University Press; 2014)

Further reading

General

- Bowers, Barbara S. Medieval Hospital And Medical Practice (2007) excerpt and text search

- Brockliss, Lawrence, and Colin Jones. "The Hospital in the Enlightenment," in The Medical World of Early Modern France (Oxford UP, 1997), pp. 671–729; covers France 1650–1800

- Chaney, Edward (2000),"'Philanthropy in Italy': English Observations on Italian Hospitals 1545–1789", in: The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed. London, Routledge, 2000. https://books.google.com/books?id=rYB_HYPsa8gC

- Goldin, Grace. Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (Yale U. P., 1975), scholarly

- Goldin, Grace. Work of Mercy: A Picture History of Hospitals (1994), popular

- Harrison, Mark, et al. eds. From Western Medicine to Global Medicine: The Hospital Beyond the West (2008)

- Henderson, John, et al., eds. The Impact of Hospitals 300–2000 (2007); 426 pages; 16 essays by scholars table of contents

- Henderson, John. The Renaissance Hospital: Healing the Body and Healing the Soul (2006).

- Horden, Peregrine. Hospitals and Healing From Antiquity to the Later Middle Ages (2008)

- Jones, Colin. The Charitable Imperative: Hospitals and Nursing in Ancient Regime and Revolutionary France (1990)

- McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History (1985)

- Morelon, Régis and Roshdi Rashed, eds. Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science (1996)

- Porter, Roy. The Hospital in History, with Lindsay Patricia Granshaw (1989) ISBN 978-0-415-00375-9

- Risse, Guenter B. Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals (1999), 716pp; world coverage excerpt and text search

- Scheutz, Martin et al. eds. Hospitals and Institutional Care in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (2009)

Nursing

- Bullough, Vern L. and Bullough, Bonnie. The Care of the Sick: The Emergence of Modern Nursing (1978).

- D'Antonio, Patricia. American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work (2010), 272pp excerpt and text search

- Davies, Celia, ed. Rewriting Nursing History (1980),

- Dingwall, Robert, Anne Marie Rafferty, Charles Webster. An Introduction to the Social History of Nursing (Routledge, 1988)

- Dock, Lavinia Lloyd. A Short history of nursing from the earliest times to the present day (1920)full text online; abbreviated version of M. Adelaide Nutting and Dock, A History of Nursing (4 vol 1907); vol 1 online; vol 3 online

- Donahue, M. Patricia. Nursing, The Finest Art: An Illustrated History (3rd ed. 2010), includes over 400 illustrations; 416pp; excerpt and text search

- Fairman, Julie and Joan E. Lynaugh. Critical Care Nursing: A History (2000) excerpt and text search

- Hutchinson, John F. Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross (1996) 448 pp.

- Judd, Deborah. A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (2009) 272pp excerpt and text search

- Lewenson, Sandra B., and Eleanor Krohn Herrmann. Capturing Nursing History: A Guide to Historical Methods in Research (2007)

- Schultheiss, Katrin. Bodies and souls: politics and the professionalization of nursing in France, 1880–1922 (Harvard U.P., 2001) full text online at ACLS e-books

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. Historical Encyclopedia of Nursing (2004), 354pp; from ancient times to the present

- Takahashi, Aya. The Development of the Japanese Nursing Profession: Adopting and Adapting Western Influences (Routledgecurzon, 2011) excerpt and text search

Hospitals in Britain

- Bostridge. Mark. Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon (2008)

- Carruthers, G. Barry. History of Britain's Hospitals (2005) excerpt and text search

- Cherry, Stephen. Medical Services and the Hospital in Britain, 1860–1939 (1996) excerpt and text search

- Gorsky, Martin. "The British National Health Service 1948-2008: A Review of the Historiography," Social History of Medicine, Dec 2008, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp. 437–460

- Helmstadter, Carol, and Judith Godden, eds. Nursing before Nightingale, 1815–1899 (Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2011) 219 pp. on England

- Nelson, Sioban, and Ann Marie Rafferty, eds. Notes on Nightingale: The Influence and Legacy of a Nursing Icon (2010) 172 pp.

- Reinarz, Jonathan. "Health Care in Birmingham: The Birmingham Teaching Hospitals, 1779–1939" (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009)

- Sweet, Helen. "Establishing Connections, Restoring Relationships: Exploring the Historiography of Nursing in Britain," Gender and History, Nov 2007, Vol. 19 Issue 3, pp. 565–80

Hospitals in North America

- Agnew, G. Harvey. Canadian Hospitals, 1920 to 1970, A Dramatic Half Century (University of Toronto Press, 1974)

- Bonner, Thomas Neville. Medicine in Chicago: 1850-1950 (1957). pp. 147–74

- Connor, J. T. H. "Hospital History in Canada and the United States," Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 1990, Vol. 7 Issue 1, pp. 93–104

- Crawford, D.S. "Bibliography of Histories of Canadian hospitals and schools of nursing".

- D'Antonio, Patricia. American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work (2010), 272pp excerpt and text search

- Fairman, Julie and Joan E. Lynaugh. Critical Care Nursing: A History (2000) excerpt and text search

- Judd, Deborah. A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (2009) 272pp excerpt and text search

- Kalisch, Philip Arthur, and Beatrice J. Kalisch. The Advance of American Nursing (2nd ed. 1986); retitled as American Nursing: A History (4th ed. 2003), the standard history

- Reverby, Susan M. Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945 (1987) excerpt and text search

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System (1995) history to 1920 table of contents and text search

- Rosner, David. A Once Charitable Enterprise: Hospitals and Health Care in Brooklyn and New York 1885–1915 (1982)

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The rise of a sovereign profession and the making of a vast industry (1984) excerpt and text search

- Stevens, Rosemary. In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century (1999) excerpt and text search; full text in ACLS e-books

- Vogel, Morris J. The Invention of the Modern Hospital: Boston 1870–1930 (1980)

- Wall, Barbra Mann. Unlikely Entrepreneurs: Catholic Sisters and the Hospital Marketplace, 1865–1925 (2005)

- Wall, Barbra Mann. American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (2010) excerpt and text search