Splenomegaly

| Splenomegaly | |

|---|---|

| |

| CT scan showing splenomegaly in a patient with chronic lymphoid leukemia | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| ICD-10 | Q89.0, R16.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 759.0, 789.2 |

| DiseasesDB | 12375 |

| MedlinePlus | 003276 |

| eMedicine | ped/2139 med/2156 |

| MeSH | D013163 |

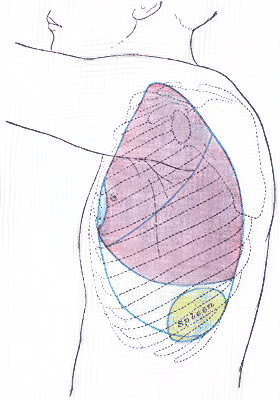

Splenomegaly is an enlargement of the spleen. The spleen usually lies in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the human abdomen. Splenomegaly is one of the four cardinal signs of hypersplenism which include; some reduction in the number of circulating blood cells affecting granulocytes, erythrocytes or platelets in any combination, a compensatory proliferative response in the bone marrow, and the potential for correction of these abnormalities by splenectomy. Splenomegaly is usually associated with increased workload (such as in hemolytic anemias), which suggests that it is a response to hyperfunction. It is therefore not surprising that splenomegaly is associated with any disease process that involves abnormal red blood cells being destroyed in the spleen. Other common causes include congestion due to portal hypertension and infiltration by leukemias and lymphomas. Thus, the finding of an enlarged spleen, along with caput medusa, is an important sign of portal hypertension.[1]

Definition

Poulin et al.[2] classify splenomegaly as:

- Moderate splenomegaly, if the largest dimension is between 11–20 cm

- Severe splenomegaly, if the largest dimension is greater than 20 cm

- Splenomegaly refers strictly to spleen enlargement, and is distinct from hypersplenism, which connotes overactive function by a spleen of any size. Splenomegaly and hypersplenism should not be confused. Each may be found separately, or they may coexist.

- Clinically if a spleen is palpable, it means it is enlarged as it has to undergo at least twofold enlargement to become palpable. However, the tip of the spleen may be palpable in a newborn baby up to 3 months of age.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may include abdominal pain, chest pain, chest pain similar to pleuritic pain when stomach, bladder or bowels are full, back pain, early satiety due to splenic encroachment, or the symptoms of anemia due to accompanying cytopenia.

Signs of splenomegaly may include a palpable left upper quadrant abdominal mass or splenic rub. It can be detected on physical examination by using Castell's sign, Traube's space percussion or Nixon's sign, but an ultrasound can be used to confirm diagnosis. In patients where the likelihood of splenomegaly is high, the physical exam is not sufficiently sensitive to detect it; abdominal imaging is indicated in such patients.[3]

Causes

The most common causes of splenomegaly in developed countries are infectious mononucleosis, splenic infiltration with cancer cells from a hematological malignancy and portal hypertension (most commonly secondary to liver disease, and Sarcoidosis). Splenomegaly may also come from bacterial infections, such as syphilis or an infection of the heart's inner lining (endocarditis).[4]

The possible causes of moderate splenomegaly (spleen <1000 g) are many, and include:

The causes of massive splenomegaly (spleen >1000 g) are fewer, and include:

- visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar)

- chronic myelogenous leukemia

- myelofibrosis

- malaria

- splenic marginal zone lymphoma

Treatment

If the splenomegaly underlies hypersplenism, a splenectomy is indicated and will correct the hypersplenism. However, the underlying cause of the hypersplenism will most likely remain; consequently, a thorough diagnostic workup is still indicated, as, leukemia, lymphoma and other serious disorders can cause hypersplenism and splenomegaly. After splenectomy, however, patients have an increased risk for infectious diseases.

Patients undergoing splenectomy should be vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Meningococcus. They should also receive annual influenza vaccinations. Long-term prophylactic antibiotics may be given in certain cases.

In cases of infectious mononucleosis splenomegaly is a common symptom and health care providers may consider using abdominal ultrasonography to get insight into a person's condition.[11] However, because spleen size varies greatly, ultrasonography is not a valid technique for assessing spleen enlargement and should not be used in typical circumstances or to make routine decisions about fitness for playing sports.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Ghazi, Ali (2010). "Hypercalcemia and huge splenomegaly presenting in an elderly patient with B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 4 (334). doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-330.

- ↑ Matacia-Murphy 'et al., Splenomegaly (Medscape, updated Apr. 2012)

- ↑ Grover SA, Barkun AN, Sackett DL (1993). "The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have splenomegaly?". JAMA. 270 (18): 2218–21. doi:10.1001/jama.270.18.2218. PMID 8411607. Ovid full text

- ↑ Kaiser, Larry R.; Pavan Atluri; Giorgos C Karakousis; Paige M Porrett (2006). The surgical review: an integrated basic and clinical science study guide. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5641-3.

- ↑ Sproat, LO.; Pantanowitz, L.; Lu, CM.; Dezube, BJ. (Dec 2003). "Human immunodeficiency virus-associated hemophagocytosis with iron-deficiency anemia and massive splenomegaly". Clin Infect Dis. 37 (11): e170–3. doi:10.1086/379613. PMID 14614691.

- ↑ Friedman, AD.; Daniel, GK.; Qureshi, WA. (Jun 1997). "Systemic ehrlichiosis presenting as progressive hepatosplenomegaly". South Med J. 90 (6): 656–60. doi:10.1097/00007611-199706000-00017. PMID 9191748.

- ↑ Neufeld EF, Muenzer J (1995). "The mucopolysaccharidoses". In Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease.7th ed. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill , New York. pp. 2465–94.

- ↑ Suvajdzić, N.; Cemerikić-Martinović, V.; Saranović, D.; Petrović, M.; Popović, M.; Artiko, V.; Cupić, M.; Elezović, I. (Oct 2006). "Littoral-cell angioma as a rare cause of splenomegaly". Clin Lab Haematol. 28 (5): 317–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00801.x. PMID 16999722.

- ↑ Dascalescu, CM.; Wendum, D.; Gorin, NC. (Sep 2001). "Littoral-cell angioma as a cause of splenomegaly". N Engl J Med. 345 (10): 772–3. doi:10.1056/NEJM200109063451016. PMID 11547761.

- ↑ Ziske, C.; Meybehm, M.; Sauerbruch, T.; Schmidt-Wolf, IG. (Jan 2001). "Littoral cell angioma as a rare cause of splenomegaly". Ann Hematol. 80 (1): 45–8. doi:10.1007/s002770000223. PMID 11233776.

- 1 2 American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (24 April 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, retrieved 29 July 2014, which cites

- Putukian, M; O'Connor, FG; Stricker, P; McGrew, C; Hosey, RG; Gordon, SM; Kinderknecht, J; Kriss, V; Landry, G (Jul 2008). "Mononucleosis and athletic participation: an evidence-based subject review". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 18 (4): 309–15. doi:10.1097/jsm.0b013e31817e34f8. PMID 18614881.

- Spielmann, AL; DeLong, DM; Kliewer, MA (Jan 2005). "Sonographic evaluation of spleen size in tall healthy athletes.". AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 184 (1): 45–9. doi:10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840045. PMID 15615949.

External links

- Splenomegaly and hypersplenism at patient.info

- Medical dictionary

- 11-141b. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition (Hypersplenism)

- /Splenomegaly and Hypersplenism