Bering Strait

Coordinates: 66°0′N 169°0′W / 66.000°N 169.000°W

The Bering Strait (Russian: Берингов пролив, Beringov proliv, Yupik: Imakpik[2][3]) is a strait of the Pacific, which borders with the Arctic to north. It is located between Russia and the United States. Named after Vitus Bering, a Danish-born explorer in the service of the Russian Empire, it lies slightly south of the Arctic Circle being at about 65° 40' N latitude. The present Russia-US east-west boundary is at 168° 58' 37" W.

The Strait has been the subject of scientific speculation that humans migrated from Asia to North America across a land bridge known as Beringia when lower ocean levels – perhaps a result of glaciers locking up vast amounts of water – exposed a wide stretch of the sea floor,[4] both at the present strait and in the shallow sea north and south of it. This view of how Paleo-Indians entered America has been the dominant one for several decades and continues to be the most accepted one.

As of 2012, the Russian coast of the Bering Strait has been a closed military zone. Through organized trips and the use of special permits, it is possible for foreigners to visit. All arrivals must be through an airport or a cruise port, near the Bering Strait only at Anadyr or Provideniya. Unauthorized travelers who arrive on shore after crossing the strait, even those with visas, may be arrested, imprisoned briefly, fined, deported and banned from future visas.[5]

Geography and science

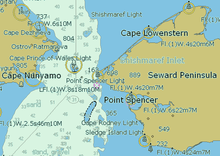

The Bering Strait is about 82 kilometres (51 mi) wide at its narrowest point, between Cape Dezhnev, Chukchi Peninsula, Russia, the easternmost point (169° 43' W) of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, United States, the westernmost point (168° 05' W) of the North American continent. Its depth varies between 30 metres (98 ft) and 50 metres (160 ft).[6] It borders with the Chukchi Sea (part of the Arctic Ocean) to north and with the Bering Sea to south.

The International Date Line runs equidistant between the Strait's Diomede Islands at a distance of 1.5 km (1 mi), leaving the Russian and American sides usually on different calendar days, with Cape Dezhnev 21 hours ahead of the American side (20 hours during daylight saving time).

Population

The area is sparsely populated.

The eastern coast belongs to the U.S. state of Alaska. Notable towns that straddle the Strait include Nome (3,788 people) and the small settlement of Teller (229 people).

The western coast belongs to the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, a Federal subject of Russia. Major towns that lie along the Strait include Lorino (1,267 people) and Lavrentiya (1,459 people).

The Diomede Islands lie midway in the Strait. The village in Little Diomede has a school which belongs to Alaska's Bering Strait School District.

Expeditions

The earliest reference of the strait were from maps from the Polo family; based on the adventures of Marco Polo.[7] From at least 1562, European geographers thought that there was a Strait of Anián between Asia and North America. In 1648, Semyon Dezhnyov probably passed through the strait, but his report did not reach Europe. Danish-born Russian navigator Vitus Bering entered it in 1728. In 1732, Mikhail Gvozdev crossed it for the first time, from Asia to America. Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld in 1878–79 sailed along the northern coast of Siberia, thereby proving that there was no northern land bridge from Asia to North America.

In March 1913, Captain Max Gottschalk (German) crossed from the east cape of Siberia to Shishmaref, Alaska, on dogsled via Little and Big Diomede islands. He was the first documented modern voyager to cross from Russia to North America without the use of a boat.[8]

In 1987, swimmer Lynne Cox swam a 4.3-kilometre (2.7 mi) course between the Diomede Islands from Alaska to the Soviet Union in 3.3 °C (37.9 °F) water during the last years of the Cold War.[9]

In June and July 1989, a British expedition, Kayaks Across the Bering Strait, completed the first sea kayak crossing of the Bering Strait from Wales (Kiŋigin), Alaska, to Cape Dezhnev, Siberia. The team of Robert Egelstaff, Trevor Potts, Greg Barton and Pete Clark landed on Little Diomede Island, rested a few days and completed the journey to Uelen. They were escorted to Moscow from where they flew back to London at the end of July.

During the first part of the crossing they were accompanied by two other groups, Paddling into Tomorrow led by Doug Van Etten. There was also small party led by Jim Noyes in a three-man Baidarka who were accompanied by a film crew. The film Curtain of Ice was produced by Aggi Orse.

In 1998, Russian adventurer Dmitry Shparo and his son Matvey made the modern crossing of the frozen Bering Strait on skis.

In March 2006, Briton Karl Bushby and French-American adventurer Dimitri Kieffer crossed the strait on foot, walking across a frozen 90 km (56 mi) section in 15 days.[10] They were soon arrested for not entering Russia through a border control.[11]

August 2008 marked the first crossing of the Bering Strait using an amphibious road-going vehicle. The specially modified Land Rover Defender 110 was driven by Steve Burgess and Dan Evans across the straits on its second attempt following the interruption of the first by bad weather.[12]

In February 2012, Korean team led by Hong Sung-Taek crossed the straits on foot in six days. They started from Chukotka Peninsula, the east coast of Russia on February 23 and arrived in Wales, the western coastal town in Alaska on February 29.[13]

In July, 2012, six adventurers associated with "Dangerous Waters", a reality adventure show under production, made the crossing on Sea-Doos but were arrested and permitted to return to Alaska on their Sea-Doos after being briefly detained in Lavrentiya, administrative center of the Chukotsky District. They were treated well and given a tour of the village's museum, but not permitted to continue south along the Pacific coast. The men had visas but the western coast of the Bering Strait is a closed military zone.[5]

Between August 4 and 10 (US dates), 2013, a team of 65 swimmers from 17 countries performed a relay swim across the Bering Strait, the first such swim in history. They swam from Cape Dezhnev, Russia, to Cape Prince of Wales, United States (roughly 110 km, due to the current).[14][15] They had direct support from the Russian Navy, using one of its ships, and assistance with permission.

Proposed tunnel

A physical link between Asia and North America via the Bering Strait nearly became a reality in 1864 when a Russian-American telegraph company began preparations for an overland telegraph line connecting Europe and America via the east. It was abandoned when the undersea Atlantic Cable proved successful.

A further proposal for a bridge-and-tunnel link from Siberia to Alaska was made by French engineer Baron Loicq de Lobel in 1906. Czar Nicholas II of Russia issued an order authorising a Franco-American syndicate represented by de Lobel to begin work on the Trans-Siberian Alaska railroad project, but no physical work ever commenced.[16][17][18][19][20]

Suggestions have been made to construct a Bering Strait bridge between Alaska and Siberia. However, despite the unprecedented engineering, political, and financial challenges, Russia green-lighted the US $65-billion TKM-World Link tunnel project in August 2011. If completed, the 103 km (64 mile) project would be the world's longest.[21] China is considering construction of a "China-Russia-Canada-America" railroad line that would include construction of a 200 km (120 mi) long underwater tunnel that would cross the Bering Strait.[22]

Proposed dam

In 1956, the Soviet Union proposed to the US a joint bi-national project to warm the Arctic Ocean and melt some of the ice cap. The Soviet project called for a 90 km (56 mi) wide dam across the Bering Straits. It would block the cold Pacific current with from entering arctic, and by pumping low-salinity cold surface water across the dam to the Pacific, warmer and higher salinity sea water from Arctic Ocean would be introduced into the ocean.[23][24]

However citing national security concerns, the CIA and FBI experts opposed the Soviet plan by arguing that while the plan was feasible, it would compromise NORAD and thus the dam could be built at only an immense cost.[25]

In 21st century, a similar dam have also been proposed, however the aim of the proposal is to preserve the Arctic ice cap against global warming.[26]

The "Ice Curtain" border

During the Cold War, the Bering Strait marked the border between the Soviet Union and the United States. The Diomede Islands—Big Diomede (Russia) and Little Diomede (US)—are only 3.8 km (2.4 mi) apart. Traditionally, the indigenous peoples in the area had frequently crossed the border back and forth for "routine visits, seasonal festivals and subsistence trade", but were prevented from doing so during the Cold War.[27] The border became known as the "Ice Curtain".[28] It was completely closed, and there was no regular passenger air or boat traffic. In 1987, American swimmer Lynne Cox symbolically helped ease tensions between the two countries by swimming across the border[29] and was congratulated jointly by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. Since 1990, tourist air and boat traffic has resumed, but is hampered by the need for visas and special military visit permits asked by US authorities and also by their Russian counterparts.

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.wall-maps.com/World/PetersProjection-over.gif

- ↑ Forbes, Jack D. 2007. The American Discovery of Europe. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 84 ff., 198,

- ↑ Stuckey, M., & J. Murphy. 2001. By Any Other Name: Rhetorical Colonialism in North America. American Indian Culture, Research Journal 25(4): 73–98, p. 80.

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- 1 2 Andrew Roth (July 11, 2012). "Journey by Sea Takes Awkward Turn in Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ↑ It is only 53 miles (85 km) wide, and at its deepest point is only 90 metres (300 ft) in depth.

- ↑ Klein, Christopher (September 30, 2014). "Did Marco Polo Visit Alaska?". History.

- ↑ The Victoria Advocate February 1 1938, additional text.

- ↑ Watts, Simon. (2012-08-08) BBC News - Swim that did not break Cold War ice curtain. Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "Epic explorer crosses frozen sea". BBC News. 3 April 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Epic explorer detained in Russia". BBC News. 4 April 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Cape to Cape Expedition". Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ The Korea Herald. "Korean team crosses Bering Strait". koreaherald.com.

- ↑ "ТАСС: Спорт - На Аляске завершилась международная эстафета "моржей", переплывших Берингов пролив". ТАСС.

- ↑ "Bering Strait Swim - Russia to America". Facebook.

- ↑ "San Francisco to St Petersburg by Rail! If the Tunnel is driven under Bering Strait will Orient meet Occident with Smile - or with Sword?". San Francisco Call. September 2, 1906. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Thinking Big: Roads and Railroads to Siberia.". InterBering LLC. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ Loicq de Lobel (August 2, 1906). "Le Klondyke, l'Alaska, le Yukon et les Iles Aléoutienne". Société Française d'Editions d'Art. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ "FOR BERING STRAIT BRIDGE". New York Times. August 2, 1906. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ James A. Oliver (2006). The Bering Strait Crossing: A 21st Century Frontier Between East and West.

- ↑ Halpin, Tony (2011-08-20). "Russia plans $65bn tunnel to America". The Sunday Times.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (2014-05-09). "China may build an undersea train to America". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ↑ http://gizmodo.com/5680669/thawing-the-arctic---soviet-russias-cold-war-war-on-cold

- ↑ http://www.vice.com/read/the-soviet-scientist-who-dreamed-of-melting-the-arctic-with-a-55-mile-dam

- ↑ "Ocean Dams Would Thaw North" Popular Mechanics, June 1956, p. 135.

- ↑ http://www.global-greenhouse-warming.com/could-a-300-km-dam-save-the-arctic.html

- ↑ State of Alaska website

- ↑ "Lifting the Ice Curtain", Peter A. Iseman, The New York Times, October 23, 1988

- ↑ "Swimming to Antarctica", CBS News, September 17, 2003

Further reading

- Oliver, James A. (2007). The Bering Strait Crossing. Information Architects. ISBN 0-9546995-6-4.

- "Russia Plans World's Longest Undersea Tunnel". Daily Tech. 2007-04-24. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bering Island, Sea and Strait". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 775–776.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bering Island, Sea and Strait". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 775–776.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bering Strait. |