Imperial Airlines Flight 201/8

Lockheed Constellation L-049 similar to accident aircraft | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | November 8, 1961 |

| Summary | Pilot error |

| Site |

Henrico County, near Richmond, Virginia 37°28′39.56″N 77°18′1.96″W / 37.4776556°N 77.3005444°WCoordinates: 37°28′39.56″N 77°18′1.96″W / 37.4776556°N 77.3005444°W |

| Passengers | 74 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 77 |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 2[1] |

| Survivors | 2 |

| Aircraft type | Lockheed L-049E Constellation |

| Operator | Imperial Airlines |

| Registration | N2737A |

Imperial Airlines Flight 201/8 was a Lockheed Constellation L-049 four-engine propliner, registration N2737A (c/n 1976), chartered by the United States Army to transport new recruits to Columbia, South Carolina, for training.[2][3] On November 8, 1961, at 21:24 Eastern Time Zone (EST), the aircraft crashed as it attempted to land at Byrd Field, near Richmond, Virginia. While there were no apparent impact-related injuries, all seventy-four passengers and three crew members died as a result of carbon monoxide asphyxiation in the ensuing fire and smoke. Two crew members—the captain and flight engineer—survived after escaping the burning wreckage.[1][4][5][6] This was the second deadliest accident in American history for a single civilian aircraft.[7]

The accident was investigated by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), which attributed the cause to numerous errors committed by the flight crew, as well as poor management and improper maintenance by the airline. The CAB concluded that the "flight crew was not capable of performing the function or assuming the responsibility for the job they presumed to do."[4]

Flight crew

The Lockheed Constellation L-049, like many airliners of its era, was normally crewed by three individuals: a captain (or pilot in command) in the left seat, a first officer (also known as copilot) in the right seat, and a flight engineer in the rear seat. The accident flight crewing was unusual in several respects.[4]

First, its first officer was also a captain, who was more senior and had more total flying time and L-049 experience than the designated captain. According to later testimony, the two captains agreed between them prior to the flight that the more senior one would serve as copilot, sitting in the right seat, while the more junior one would serve as pilot in command, sitting in the left seat.[4]

Second, the person who was actually sitting in the flight engineer's position was a trainee, a "student flight engineer", under supervision of the official flight engineer assigned to the flight, who was sitting next to him.[4]

As would emerge in later testimony at the post-crash hearing, this crewing combination led to confusion in the cockpit during the final flight segment, as to who was making the decisions and giving the orders as pilot in command, and who was operating the engine and fuel controls as flight engineer.[4]

Flight history

The four-engined chartered propliner departed Columbia, South Carolina, at 15:24 EST, and landed in Newark, New Jersey, at 17:37, where it picked up its first group of 26 passengers. It departed at 18:22 for Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, where it picked up 31 additional passengers. At 19:12 it departed for Baltimore, Maryland, where it picked up a final group of 17 passengers and departed for South Carolina at 20:30. During these flight segments, as he would later testify at the CAB hearing, the flight engineer opened the cross feed valves between the number three and four engines, since he had seen a drop in fuel pressure on the number 3 fuel pressure gauge after the initial takeoff from Columbia.[4]

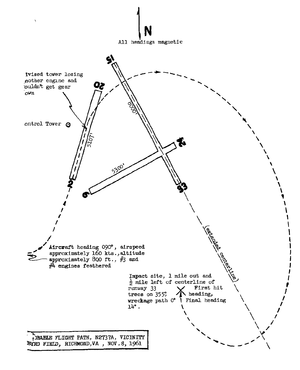

During the final flight segment from Baltimore to Columbia, the crew experienced fuel flow disruptions to both right side engines, eventually leading both of them to shut down, after multiple unsuccessful attempts by the crew to restore proper fuel flow and engine operation. Flying with asymmetric thrust from the two left side engines (which were operating normally at that point), the captain decided to land in Byrd Field (now called Richmond International Airport), near Richmond, Virginia, as a precaution.[4]

Crash

As the crew attempted to extend the gear for landing, they encountered difficulties, since hydraulic power to the landing gear in that aircraft was normally supplied by the two right side engines, now shut down. The crew initially selected runway 33 for landing, then decided on runway 02, and when they realized they were too high for landing on runway 02, they decided to climb and go around for runway 33 again. While climbing on the two operating engines, with asymmetric thrust, the number one engine (outboard on left side) failed due to over-boosting, leading to a rapid loss of airspeed and eventual stall. The aircraft crashed into trees, and a fire broke out which engulfed the entire aircraft in flames and smoke. The captain and flight engineer were able to escape, but all others were trapped inside the wreckage and were overcome by carbon monoxide poisoning before they could exit, as later autopsies would reveal.[4]

Investigation

The accident was investigated by the CAB and included two hearings where, among others, the surviving captain and flight engineer testified. Based on their investigation, the CAB concluded that the momentary fuel pressure fluctuations in the number 3 and 4 (right side) engines noticed by the flight engineer during takeoff, were most likely caused by a boost pump failure, and did not necessitate any action as long as the engines kept running normally. According to the CAB, by opening the cross-feed valves between the number 3 and 4 fuel tanks, and leaving them open with the boost pump on for much of the flight, the flight engineer most likely caused the number 4 tank to run dry, resulting in the failure of both right side engines due to fuel exhaustion or starvation during the final flight segment.[4][8]

The CAB concluded that, had proper fuel management procedures been followed, all engines would have kept running normally, or even restarted once they shut down. The Constellation crew, however, mismanaged the fuel flow to the right side engines, causing them to shut down, and were unable to restart them. During the ensuing precautionary landing which resulted in the crash, additional flight crew mistakes were highlighted by the CAB investigators, who were highly critical of Imperial Airlines management, maintenance and flying procedures. The CAB's final report stated:[4]

From a study of all the information available to the Board it is concluded that this flight crew was not capable of performing the function or assuming the responsibility for the job they presumed to do. The Board further concludes that the management personnel of Imperial Airlines should have been aware of the manner in which company operations were being accomplished. It is believed that the substandard maintenance practices of Imperial's employees were condoned by management. The manner in which maintenance and personnel records were kept by the company confirms this conclusion.

The CAB issued the following Probable Cause statement:[4]

The Board determines the probable cause of this accident was the lack of command coordination and decision, lack of judgment, and lack of knowledge of the equipment resulting in loss of power in three engines creating an emergency situation which the crew could not handle.

Aftermath

After the accident, it was revealed that Imperial Airlines had been fined in 1959 for "flying 30 marines in an 'unairworthy' C-46," and in 1953, under its previous name of "Regina Cargo Airlines", 19 soldiers had been killed in a crash near Centralia, Washington, while being transported in a Douglas DC-3 owned by the company.[3]

Time news magazine reported that statistically the "nonskeds" in general were "more than 30 times as dangerous" in the number of fatalities per passenger mile as the scheduled airlines in 1961.[9] According to Time, the U.S. military had been effectively forced to rely on nonskeds such as Imperial Airlines to carry troops within the U.S. because of the combination of two laws. First, the Congress had mandated the use of civilian air carriers (for economic reasons); and second, the Pentagon was obligated to bid for such services and select the lowest bidder, which often turned out to be financially unsound companies with a poor safety record.[3]

As a result of the accident, the Congress became concerned about the safety practices of the nonskeds, or "supplemental carriers." The chairman of the Senate Aviation Subcommittee, A. S. Mike Monroney immediately sent a telegram to the CAB, urging a sweeping probe of the supplemental carrier industry.[10] By 1962, Congress passed a law requiring all supplemental carriers to re-apply for certification by the CAB, to carry liability insurance and to maintain "a healthier financial status."[9] The new rules caused some 20 nonskeds to go out of business, but within five years the industry was booming again, partly due to the troop and equipment carrying needs of the Vietnam War.[11]

See also

- Air Tahoma Flight 185 – another propliner accident caused by fuel cross-feed mismanagement

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

Notes

- 1 2 "Probe Of Air Crash Under Way". AP on Logansport Press, Logansport, IN. November 10, 1961. p. 1.

- ↑ "ASN crash record". ASN. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- 1 2 3 "What Did Matter". Time Magazine. November 17, 1961.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "CAB Aircraft Accident Report" (PDF). CAB. Retrieved 2009-06-05. (see DOT archive external link below to access PDF file)

- ↑ "A Few Discrepancies". Time Magazine. December 15, 1961.

- ↑ "Suffocation Claims Most Crash Victims". UPI in The Valley Independent, Monessen, PA. November 10, 1961. p. 1.

- ↑ "74 young recruits - Air Crash Killed 77 - On last leg of trip when tragedy struck". UPI on Ames Daily Tribune, Ames, IA. November 11, 1961.

- ↑ The flight engineer denied in his testimony that he had left the cross feed valves and boost pumps on during cruise flight, but the CAB discounted his testimony based on the preponderance of the other testimony and evidence.

- 1 2 "Off the Schedule". Time Magazine. September 21, 1962.

- ↑ "Crash May Set off Sweeping Probe - Clamor for Crackdown on Carriers". UPI in The Valley Independent, Monessen, PA. November 10, 1961. p. 5.

- ↑ "High-Flying Supplemental". Time Magazine. June 30, 1967.

External links

- Smoldering tail of N2737A guarded by military police after crash (on www.baaa-acro.com)

- DOT accident archive site (To retrieve original report copy in PDF format: Historical Aviation Accident reports, 1961, Imperial Airlines, PDF)