Incunable

An incunable, or sometimes incunabulum (plural incunables or incunabula, respectively), is a book, pamphlet, or broadside (such as the Almanach cracoviense ad annum 1474) that was printed—not handwritten—before the year 1501 in Europe. "Incunable" is the anglicised singular form of "incunabula", Latin for "swaddling clothes" or "cradle",[1] which can refer to "the earliest stages or first traces in the development of anything."[2] A former term for "incunable" is "fifteener", referring to the 15th century.

The first recorded use of incunabula as a printing term is in the Latin pamphlet De ortu et progressu artis typographicae ("Of the rise and progress of the typographic art", Cologne, 1639) by Bernhard von Mallinckrodt, which includes the phrase prima typographicae incunabula, "the first infancy of printing", a term to which he arbitrarily set an end of 1500 which still stands as a convention.[3] The term came to denote the printed books themselves in the late 17th century. John Evelyn, in moving the Arundel Manuscripts to the Royal Society in August 1678, remarked of the printed books among the manuscripts: "The printed books, being of the oldest impressions, are not the less valuable; I esteem them almost equal to MSS."[4]

The convenient but arbitrarily chosen end date for identifying a printed book as an incunable does not reflect any notable developments in the printing process, and many books printed for a number of years after 1500 continued to be visually indistinguishable from incunables. "Post-incunable" typically refers to books printed after 1500 up to another arbitrary end date such as 1520 or 1540.

As of 2014, there are about 30,000 distinct incunable editions known to be extant, while the number of surviving copies in Germany alone is estimated at around 125,000.[5][6]

Types

There are two types of incunabula in printing: the Block book printed from a single carved or sculpted wooden block for each page, by the same process as the woodcut in art (these may be called xylographic), and the typographic book, made with individual pieces of cast metal movable type on a printing press. Many authors reserve the term incunabula for the typographic ones only.[7]

The spread of printing to cities both in the north and in Italy ensured that there was great variety in the texts chosen for printing and the styles in which they appeared. Many early typefaces were modelled on local forms of writing or derived from the various European forms of Gothic script, but there were also some derived from documentary scripts (such as most of Caxton's types), and, particularly in Italy, types modelled on handwritten scripts and calligraphy employed by humanists.

Printers congregated in urban centres where there were scholars, ecclesiastics, lawyers, nobles and professionals who formed their major customer base. Standard works in Latin inherited from the medieval tradition formed the bulk of the earliest printing, but as books became cheaper, works in the various local vernaculars (or translations of standard works) began to appear.

Famous examples

Incunabula include the Gutenberg Bible of 1455, the Peregrinatio in terram sanctam of 1486—printed and illustrated by Erhard Reuwich—both from Mainz, the Nuremberg Chronicle written by Hartmann Schedel and printed by Anton Koberger in 1493, and the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili printed by Aldus Manutius with important illustrations by an unknown artist. Other printers of incunabula were Günther Zainer of Augsburg, Johannes Mentelin and Heinrich Eggestein of Strasbourg, Heinrich Gran of Haguenau and William Caxton of Bruges and London. The first incunable to have woodcut illustrations was Ulrich Boner's Der Edelstein, printed by Albrecht Pfister in Bamberg in 1461.[8]

Statistical data

The data in this section were derived from the Incunabula Short-Title Catalogue (ISTC).[9]

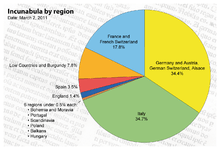

- Printing towns: The number of printing towns and cities stands at 282. These are situated in some 18 countries in terms of present-day boundaries. In descending order of the number of editions printed in each, these are: Italy, Germany, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, England, Austria, the Czech Republic, Portugal, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Turkey, Croatia, Montenegro, and Hungary (see diagram below). The following table shows the 20 main 15th century printing locations; as with all data in this section, exact figures are given, but should be treated as close estimates (the total editions recorded in ISTC at May 2013 is 28,395):

| Town or city | No. of editions | % of ISTC recorded editions |

|---|---|---|

| Venice | 3,549 | 12.5 |

| Paris | 2,764 | 9.7 |

| Rome | 1,922 | 6.8 |

| Cologne | 1,530 | 5.4 |

| Lyon | 1,364 | 4.8 |

| Leipzig | 1,337 | 4.7 |

| Augsburg | 1,219 | 4.3 |

| Strasbourg | 1,158 | 4.1 |

| Milan | 1,101 | 3.9 |

| Nuremberg | 1,051 | 3.7 |

| Florence | 801 | 2.8 |

| Basel | 786 | 2.8 |

| Deventer | 613 | 2.2 |

| Bologna | 559 | 2.0 |

| Antwerp | 440 | 1.5 |

| Mainz | 418 | 1.5 |

| Ulm | 398 | 1.4 |

| Speyer | 354 | 1.2 |

| Pavia | 337 | 1.2 |

| Naples | 323 | 1.1 |

| TOTAL | 22,024 | 77.6 |

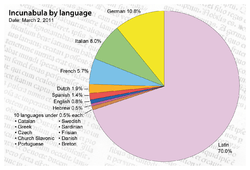

- Languages: The 18 languages that incunabula are printed in, in descending order, are: Latin, German, Italian, French, Dutch, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Catalan, Czech, Greek, Church Slavonic, Portuguese, Swedish, Breton, Danish, Frisian, Sardinian and Occitan(see diagram below).

- Illustrations: Only about one edition in ten (i.e. just over 3,000) has any illustrations, woodcuts or metalcuts.

- Survival: The 'commonest' incunable is Schedel's Nuremberg Chronicle ("Liber Chronicarum") of 1493, with c 1,250 surviving copies (which is also the most heavily illustrated). Very many incunabula are unique, but on average about 18 copies survive of each. This makes the Gutenberg Bible, at 48 or 49 known copies, a relatively common (though extremely valuable) edition.

- Total number of volumes: Counting extant incunabula is complicated by the fact that most libraries consider a single volume of a multi-volume work as a separate item, as well as fragments or copies lacking more than half the total leaves. A complete incunable may consist of a slip, or up to ten volumes.

- Formats: In terms of format, the 29,000-odd editions comprise: 2,000 broadsides, 9,000 folios, 15,000 quartos, 3,000 octavos, 18 12mos, 230 16mos, 20 32mos, and 3 64mos.

- Caxton: ISTC at present cites 528 extant copies of books printed by Caxton, which together with 128 fragments makes 656 in total, though many are broadsides or very imperfect (incomplete).

- Dispersal: Apart from migration to mainly North American and Japanese universities, there has been remarkably little movement of incunabula in the last five centuries. None were printed in the Southern Hemisphere, and the latter appears to possess less than 2,000 copies – i.e. about 97.75% remain north of the equator. However many incunabula are sold at auction or through the rare book trade every year.

Major collections

The British Library's Incunabula Short Title Catalogue now records over 29,000 titles, of which around 27,400 are incunabula editions (not all unique works). Studies of incunabula began in the 17th century. Michel Maittaire (1667–1747) and Georg Wolfgang Panzer (1729–1805) arranged printed material chronologically in annals format, and in the first half of the 19th century, Ludwig Hain published, Repertorium bibliographicum— a checklist of incunabula arranged alphabetically by author: "Hain numbers" are still a reference point. Hain was expanded in subsequent editions, by Walter A. Copinger and Dietrich Reichling, but it is being superseded by the authoritative modern listing, a German catalogue, the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke, which has been under way since 1925 and is still being compiled at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. North American holdings were listed by Frederick R. Goff and a worldwide union catalogue is provided by the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue.[10]

Notable collections, with the approximate numbers of incunabula held, include:

| Library | Location | Number of copies | Number of editions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bavarian State Library | Munich | 20,000 | 9,756 | [11] |

| British Library | London | 12,500 | 10,390 | [12] |

| Bibliothèque nationale de France | Paris | 12,000 | 8,000 | [13] |

| Vatican Library | Vatican City | 8,600 | 5,400 (more than) | [14] |

| Austrian National Library | Vienna | 8,000 | [15] | |

| Württembergische Landesbibliothek | Stuttgart | 7,076 | ||

| National Library of Russia | Saint Petersburg | 7,000 | ||

| Bodleian Library | Oxford | 6,755 | 5,623 | [16] |

| Library of Congress | Washington, DC | 5,600 | ||

| Huntington Library | San Marino, CA | 5,537 | 5,228 | |

| Russian State Library | Moscow | 5,300 | ||

| Cambridge University Library | Cambridge | 4,650 | [17] | |

| Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III | Naples | 4,563 | [18] | |

| John Rylands Library | Manchester | 4,500 | ||

| Danish Royal Library | Copenhagen | 4,425 | [19] | |

| Berlin State Library | Berlin | 4,442 | [20] | |

| Harvard University | Cambridge, Massachusetts | 4,389 | 3,627 | [21] |

| National Library of the Czech Republic | Prague | 4,200 | [22] | |

| National Central Library (Florence) | Florence | 4,000 | [23] | |

| Jagiellonian Library | Cracow | 3,671 | [24] | |

| Yale University (Beinecke) | New Haven, Connecticut | 3,525 (all collections) | ||

| Herzog August Library | Wolfenbüttel | 3,477 | 2,835 | [25] |

| Biblioteca Nacional de España | Madrid | 3,159 | 2,298 | [26] |

| Biblioteca Marciana | Venice | 2,883 | ||

| Uppsala University Library | Uppsala | 2,500 | [27] | |

| Biblioteca comunale dell'Archiginnasio | Bologna | 2,500 | [28] | |

| Bibliothèque Mazarine | Paris | 2,370 | [29] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale | Colmar | 2,300 | [30] | |

| University and State Library Tirol | Innsbruck | 2122 | 1889 | [31] |

| Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire | Strasbourg | 2,098 (circa) | [32] | |

| Morgan Library | New York | 2,000 (more than) | ||

| Newberry Library | Chicago | 2,000 (more than) | [33] | |

| National Central Library (Rome) | Rome | 2,000 | [34] | |

| National Library of the Netherlands | The Hague | 2,000 | ||

| National Széchényi Library | Budapest | 1,814 | ||

| University Library Heidelberg | Heidelberg | 1,800 | ||

| Abbey library of Saint Gall | St. Gallen | 1,650 | ||

| Turin National University Library | Turin | 1,600 | [35] | |

| Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal | Lisbon | 1,597 | [36] | |

| Biblioteca Universitaria di Padova | Padua | 1,583 | [37] | |

| Strahov Monastery Library | Prague | 1,500 (more than) | [38] | |

| Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève | Paris | 1,450 | [39] | |

| Walters Art Museum | Baltimore, Maryland | 1,250 | [40] | |

| Bryn Mawr College | Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania | 1,214 | ||

| Bibliothèque municipale | Lyon | 1,200 | [41] | |

| Biblioteca Colombina | Seville | 1,194 | [42] | |

| University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign | Urbana, Illinois | 1,100 (more than) | [43] | |

| Bridwell Library | Dallas, Texas | 1,000 (more than) | [44] | |

| University of Glasgow | Glasgow, UK | 1,000 (more than) | [45] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale de Besançon | Besançon | 1,000 (circa) | ||

| Huntington Library | San Marino, California | 827 | [46] | |

| Free Library of Philadelphia | Philadelphia | 800 (more than) | ||

| Princeton University Library | Princeton, New Jersey | 750 (including the Scheide Library) | ||

| Leiden University Library | Leiden | 700 | ||

| Bibliothèque municipale | Grenoble | 654 | ||

| Bibliothèque municipale | Avignon | 624 | [47] | |

| Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire | Fribourg (Switzerland) | 617 | 537 | [48] |

| Bibliothèque de la Sorbonne | Paris | 614 (including the Victor Cousin collection) | [49] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale | Cambrai | 600 | ||

| National Library of Medicine | Bethesda, Maryland | 580 | [50] | |

| Humanist Library of Sélestat | Sélestat | 550 | [51] | |

| Médiathèque de la Vieille Île | Haguenau | 541 | [52] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale | Rouen | 535 | ||

| Boston Public Library | Boston | 525 | ||

| Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine | Kyiv | 524 | ||

| Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile | Padua | 483 | [53] | |

| Univerzitná knižnica v Bratislave | Bratislava | 465 | ||

| Bibliothèque de Genève | Geneva | 464 | ||

| Bibliothèque municipale | Metz | 463 | ||

| Folger Shakespeare Library | Washington, D.C. | 450 (circa) | [54] | |

| University of Michigan Library | Ann Arbor, Michigan | 450 (circa) | [55] | |

| Fondazione Ugo Da Como | Lonato del Garda, Italy | 450 | ||

| Brown University Library | Providence, Rhode Island | 450 | [56] | |

| Bancroft Library | Berkeley, California | 430 | ||

| University of Zaragoza | Zaragoza | 406 | ||

| The College of Physicians of Philadelphia | Philadelphia | 400 (more than) | ||

| Médiathèque de la ville et de la communauté urbaine | Strasbourg | 394 (5,000 destroyed by fire in the 1870 Siege of Strasbourg) | [57][58] | |

| Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin | Austin, Texas | 380 | [59] | |

| National Library of Finland | Helsinki | 375 | [60] | |

| State Library of Victoria | Melbourne | 355 | [61] | |

| University of Chicago Library | Chicago | 350 (more than) | [62] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale | Bordeaux | 333 | [63] | |

| Smithsonian Institution Libraries | Washington, DC | 320 | ||

| Vilnius University Library | Vilnius | 327 | [64] | |

| Bibliothèque universitaire de Médecine | Montpellier | 300 | [65] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale | Douai | 300 | ||

| Bibliothèque municipale | Amiens | 300 | ||

| University of Seville | Seville | 298 | [66] | |

| Bibliothèque municipale | Poitiers | 289 | ||

| National Library of Wales | Aberystwyth | 250 | [67] | |

| Bibliothèque du Grand Séminaire | Strasbourg | 238 | [68] | |

| State Library of New South Wales | Sydney | 236 | [69] | |

| Library of the Kynžvart Castle | Lazne Kynzvart | 230 | [70] | |

| Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America | New York | 216 | [71] | |

| Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto | Toronto | 200 (more than) | [72] | |

| Latimer Family Library at Saint Vincent College | Latrobe, Pennsylvania | 200 (circa) | [73] | |

| Stanford University Libraries | Palo Alto, California | 178 | [74] | |

| Cardiff University Library | Cardiff, UK | 173 | [75] | |

| National Library of Greece | Athens, Greece | 149 | ||

| Médiathèque protestante de Strasbourg | Strasbourg | 94 | [76] | |

| National Library of Malta | Valletta | 60 | [77] | |

| Odesa National Research Library | Odessa | 52 | ||

| Lviv National Scientific Library | Lviv | 49 | ||

| Bibliothèque centrale / Grand'rue | Mulhouse | 18 (7 [library] + 10 [fonds Armand Weiss] + 1 [fonds Gérard]) | [78][79][80] |

Post-incunable

The end date for identifying a printed book as an incunable is convenient but was chosen arbitrarily; it does not reflect any notable developments in the printing process around the year 1500. Books printed for a number of years after 1500 continued to look much like incunables, with the notable exception of the small format books printed in italic type introduced by Aldus Manutius in 1501. The term post-incunable is sometimes used to refer to books printed "after 1500—how long after, the experts have not yet agreed."[81] For books printed on the Continent, the term generally covers 1501–1540, and for books printed in the UK, 1501–1520.[81]

See also

References

- ↑ C.T. Lewis and C. Short, A Latin dictionary, Oxford 1879, p. 930. The word incunabula is a neuter plural; the singular incunabulum is never found in Latin and not used in English by most specialists.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 1933, I:188.

- ↑ Glomski, J (2001). "Incunabula Typographiae: seventeenth-century views on early printing". The Library. 2: 336. doi:10.1093/library/2.4.336.

- ↑ Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn From 1641 to 1705/6.

- ↑ British Library: Incunabula Short Title Catalogue gives 30,375 editions as of March 2014, which also includes some prints from the 16th century though (retrieved 23 July 2015).

- ↑ According to Bettina Wagner: "Das Second-Life der Wiegendrucke. Die Inkunabelsammlung der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek", in: Griebel, Rolf; Ceynowa, Klaus (eds.): "Information, Innovation, Inspiration. 450 Jahre Bayerische Staatsbibliothek", K G Saur, München 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-11772-5, pp. 207–224 (207f.) the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue lists 30,375 titles published before 1501.

- ↑ Oxford Companion to the Book, ed. M.F. Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen, OUP, 2010, s.v. 'Incunabulum', p. 815.

- ↑ Daniel De Simone (ed), A Heavenly Craft: the Woodcut in Early Printed Books, New York, 2004, p. 48.

- ↑ BL.uk, consulted in 2007. The figures are subject to slight change as new copies are reported. Exact figures are given but should be treated as close estimates; they refer to extant editions.

- ↑ "ISTC". Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- ↑ "Incunabula". Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ↑ "Incunabula Collections". British Library. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ↑ "Les Incunables". Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 2013-09-07.

- ↑ "All catalogues". Vatican Library. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "Research on Holdings". Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- ↑ "Rare Books (Western) - Bodleian Library". Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- ↑ "Incunabula Cataloguing Project". Cambridge University Library. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ↑ "Guida rapida: Informazioni utili" (in Italian). Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ Catalogue of Incunables at the Danish Royal Library

- ↑ "Zahlen und Fakten" (in German). Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ Whitesell, David (2006). First supplement to James E. Walsh's Catalogue of the fifteenth-century printed books in the Harvard University Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Library. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-674-02145-7. OCLC 71691077.

- ↑ "Incunabula". National Library of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ "La Biblioteca - Informazioni generali - Patrimonio librario" (in Italian). Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ "The Jagiellonian University Library Collection". Biblioteka Jagiellońska. 2009-12-31. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ "Herzog August Library - Inkunabeln -Bestandsgeschichte" (in German). Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ↑ "Biblioteca Nacional de España - Colecciones - Incunables" (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de España. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ↑ http://www.ub.uu.se/arv/special/einkunab.cfm Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Raccolte - Opere a stampa" (in Italian). Biblioteca comunale dell'Archiginnasio. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Collections" (in French). Bibliothèque Mazarine. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Patrimoine : Manuscrits et Livres anciens" (in French). Bibliothèque de Colmar. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ "Inkunabeln" (in German). Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- ↑ "Les incunables" (in French). Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ "Incunabula Short Title Catalogue". British Library. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

- ↑ "Collezioni" (in Italian). Biblioteca nazionale centrale di Roma. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Incunaboli" (in Italian). Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Incunabula". Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ "Il patrimonio bibliografico" (in Italian). Biblioteca Universitaria di Padova. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Concise history of the monastic library". Royal Canonry of Premonstratensians at Strahov. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ "Les imprimés" (in French). Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Manuscript and Rare Books". Walters Art Museum. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon" (in French). Lectura. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "Institución Colombina - Biblioteca Colombina - Incunables" (in Spanish). Institución Colombina. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ↑ "Rare Books". Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ↑ "Incunabula: Printing in Europe before 1501". Bridwell Library, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ↑ "Glasgow Incunabula Project". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ↑ http://catalog.huntington.org/search/X?SEARCH=%28ad%29%20or%20%28ein%29%20or%20%28del%29%20or%20%28da%29&Db=1501&SORT=D&m=a&b=stack. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Médiathèque Ceccano" (in French). Mairie d'Avignon. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ↑ Catalogue des incunables du canton de Fribourg par Romain Jurot. Avec la collaboration de Joseph Leisibach et Angéline Rais. Fribourg : Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, 2015. ISBN 978-2-9700704-9-8.

- ↑ Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne. Bibliotheque.sorbonne.fr. Retrieved on 2011-02-20.

- ↑ U.S. National Library of Medicine, History of Medicine Division. http://nlm.nih.gov/hmd. Retrieved on 2012-02-29.

- ↑ "La Bibliothèque Humaniste en quelques chiffres & dates" (in French). Bibliothèque Humaniste de Sélestat. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ↑ "Médiathèque de la Vieille Ile. Haguenau, Bas-Rhin" (in French). Catalogue collectif de France (CCFr). Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑

- ↑ "Printed Books". Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ↑ "Collections". Special Collections Library, The University of Michigan. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ↑ https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Medieval_Studies/brown/

- ↑ "Strasbourg - Médiathèque André Malraux" (in French). Catalogue collectif de France (CCFr). Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ La bibliothèque municipale de Strasbourg | Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France. Bbf.enssib.fr. Retrieved on 2011-02-20.

- ↑ "Incunabula". Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- ↑ "Åbo Akademis biblioteks inkunabler" (in Swedish). Åbo Akademi University. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ http://search.slv.vic.gov.au/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?ct=facet&fctN=facet_genre&fctV=Specimens&rfnGrp=1&rfnGrpCounter=1&frbg=&&indx=1&fn=search&dscnt=0&vl(1UIStartWith0)=contains&scp.scps=scope%3A(ROSETTA_OAI)%2Cscope%3A(SLV_VOYAGER)%2Cscope%3A(SLV_DIGITOOL)%2Cscope%3A(SLVPRIMO)&vl(10247183UI0)=any&vid=MAIN&mode=Basic&ct=search&srt=rank&tab=default_tab&dum=true&vl(freeText0)=incunabula%20specimens&dstmp=1474273036118. Retrieved 2016-09-19. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Rare Book Collections". University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ↑ Bordeaux : Culture – Bibliothèque. Bordeaux.fr. Retrieved on 2011-02-20.

- ↑ Vilnius University Library. Retrieved on 2013-10-29.

- ↑ (French) Patrimoine documentaire / Documentation / Université Montpellier 1 – Université Montpellier 1. Univ-montp1.fr. Retrieved on 2011-02-20.

- ↑

- ↑ [Hand-list of Incunabula in the National Library of Wales compiled by Victor Scholderer (N.L.W. Journal Supplement Series 1, No. 1, 1940)]

- ↑ "La bibliothèque ancienne du Grand Séminaire" (in French). Séminaire Sainte Marie Majeure - Diocèse de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ specimens&searchscope=2 "Incunabula specimen search" Check

|url=value (help). SL-NSW. Retrieved 2016-09-19. - ↑ Kynžvart Castle: Library (Czech)

- ↑ "Incunabula". University of Toronto. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- ↑ First Impressions: Hebrew Printing in the Fifteenth Century, The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary. Jtsa.edu. Retrieved on 2011-02-20.

- ↑ Latimer Family Library brochure, May 2015.

- ↑ Guide to the Incunabula Collection at Stanford University, 1467-1500

- ↑ List of incunabula in Special Collections and Archives, Cardiff University

- ↑ "Catalogue de la Médiathèque protestante". Médiathèque protestante. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ↑ "Collections". Malta Libraries. Ministry for Education. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "Bibliothèque-médiathèque. Mulhouse, Haut-Rhin" (in French). Catalogue collectif de France. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

- ↑ "Armand Weiss" (in French). Catalogue collectif de France. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

- ↑ "Gérard" (in French). Catalogue collectif de France. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

- 1 2 Carter, John; Barker, Nicolas (2004). ABC for Book Collectors (PDF) (8th ed.). New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press and the British Library. p. 172. ISBN 1-58456-112-2. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Incunabula. |

- Centre for the History of the Book

- British Library worldwide Incunabula Short Title Catalogue

- Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW), partially English version

- History of Incunabula Studies

- UIUC Rare Book & Manuscript Library

- Grand Valley State University Incunabula & 16th Century Printing digital collections

- Incunable Collection at the Library of Congress

- Digital facsimiles of several incunabula from the website of the Linda Hall Library