Indus river dolphin

| Indus river dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

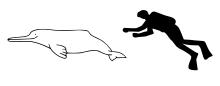

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Platanistidae |

| Genus: | Platanista |

| Species: | P. gangetica |

| Subspecies: | P. g. minor |

| Trinomial name | |

| Platanista gangetica minor | |

| |

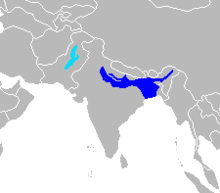

| Ranges of the Ganges River dolphin and of the Indus River dolphin | |

The Indus river dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor) is a subspecies of freshwater river dolphin found in the Indus river (and its Beas and Sutlej tributaries) of India and Pakistan. This dolphin was the first discovered side-swimming cetacean. It is patchily distributed in five small, sub-populations that are separated by irrigation barrages.[2] The Indus dolphin does not form easily defined groups who interact. Instead, they're typically found in loose aggregations.[2] From the 1970s until 1998, the Ganges River dolphin and the Indus dolphin were regarded as separate species; however, in 1998, their classification was changed from two separate species to subspecies of a single species (see taxonomy below). It has been named as the national mammal of Pakistan.[3]

Other names

- Indus River Dolphin, Indus Blind Dolphin, side-swimming dolphin

- Known locally in Pakistan as "Bhulan", a word which comes from (Sindhi: ٻلهڻ)

Taxonomy

The species was described by two separate authors Lebeck and Roxburgh in the year 1801 and it is unclear to whom the original description should be ascribed.[4] Until the 1970s the Indus and Ganges river dolphins were regarded as a single species. The two populations are geographically separate and have not interbred for many hundreds if not thousands of years. Based on differences in skull structure, vertebrae and lipid composition scientists declared the two populations as separate species in the early 1970s.[5] In 1998 the results of these studies were questioned and the classification reverted to the pre-1970 consensus of a single species containing two subspecies until the taxonomy could be resolved using modern techniques such as molecular sequencing. The latest analyses of mitochondrial DNA of the two subspecies did not display the variances needed to support their classification as separate species.[6] Thus, at present, there are two subspecies recognized in the genus Platanista: Platanista gangetica minor (the Indus dolphin) and Platanista gangetica gangetica (the Ganges river dolphin).[7]

Distribution

The Indus River Dolphin only occurs in the Indus River system.[2] These dolphins occupied about 3,400 km of the Indus River and the tributaries attached to it in the past.[2] But today, its only found in one fifth of this previous range.[8] Its effective range today has declined by 80% since 1870.[2] It no longer exists throughout the tributaries, and its home range is only 690 km of the river.[2] This dolphin prefers a freshwater habitat with a water depth greater than 1 meter and that have more than 700 meters squared of cross-sectional area. Today this species can only be found in the Indus River's main stem.

Physical Description and Diet

The Indus dolphin has the long, pointed nose characteristic of all river dolphins. The teeth are visible in both the upper and lower jaws even when the mouth is closed. The teeth of young animals are almost an inch long, thin and curved; however, as animals age the teeth undergo considerable changes and in mature adults become square, bony, flat disks. The snout thickens towards its end. The species does not have a crystalline eye lens, rendering it effectively blind, although it may still be able to detect the intensity and direction of light. Navigation and hunting are carried out using echolocation. The body is a brownish color and stocky at the middle. The species has a small triangular lump in place of a dorsal fin. The flippers and tail are thin and large in relation to the body size, which is about 2-2.2 meters in males and 2.4–2.6 meters in females. The oldest recorded animal was a 28-year-old male 199 centimeters in length.[9] Mature adult females are larger than males. Sexual dimorphism is expressed after females reach about 150 cm; the female rostrum continues to grow after the male rostrum stops growing, eventually reaching approximately 20 cm longer. Calves have been observed between January and May and do not appear to stay with the mother for more than a few months. Gestation is thought to be approximately 9–10 months.The species feeds on a variety of crustaceans and fish, including prawns, carp, catfish, gobies, etc.

Human Interaction

The Indus river dolphin has been very adversely affected by human use of the river systems in the sub-continent. Entanglement in fishing nets can cause significant damage to local population numbers. Some individuals are still taken each year and their oil and meat used as a liniment, as an aphrodisiac and as bait for catfish. Irrigation has lowered water levels throughout their ranges. Poisoning of the water supply from industrial and agricultural chemicals may have also contributed to population decline. Perhaps the most significant issue is the building of dozens of dams along many rivers, causing the segregation of populations and a narrowed gene pool in which dolphins can breed. There are currently three sub-populations of Indus dolphins considered capable of long-term survival if protected.[2]

Conservation and Status

The Indus river dolphin is listed by the IUCN as endangered on their Red List of Threatened Species [1] and by the U.S. government National Marine Fisheries Service under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. It is the second most endangered cetacean in the world. It is estimated that there are only about 1,200 individuals remaining.[2] However, not a lot is known because this species is not very well studied. There are many threats to their survival. Reckless and extensive fishing that reduces their prey availability is a large factor.[8] Also, they are sometimes accidentally entangled in the fishing nets which can cause fatalities.[8] Deforestation that occurs along the river basin is causing sedimentation which degrades the dolphin's habitat.[8] Another factor in their decline is the construction of cross-river structures such as dams and barrages. These are a problem because they cause more isolation in the already small sub-populations.[8] Lastly, human induced water pollution is a major threat factor. This pollution is usually in the form of either industrial and human waste, or agricultural run-off containing high amounts of chemical fertilizers and poisonous pesticides.[8] Studies suggest that a good understanding of this species ecology is needed in order to develop good conservation plans. Regular monitoring is also a necessity to assess the population's status and factors causing its decline.[8] There are currently a few organizations that are helping to conserve the Indus dolphin. The World Wildlife Fund(WWF) is involved in rescue missions and helping to reduce pollution in the river. In addition, WWF Pakistan is assisting in educating the public. They have even arranged training courses for many institutions. Lastly, CITES (Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species) prohibits the hunting and trade of many endangered species, including this one. Although these efforts are a start, the Indus River dolphin's future is still uncertain because it's not very well studied.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 Smith, B. D. & G. T. Braulik (2008). "Platanista gangetica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 14 December 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Braulik, G.T. (2006). "Status assessment of the Indus river dolphin, Platanista gangetica minor, March–April 2001". Biological Conservation. 129: 579–590. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.026.

- ↑ "The Official Web Gateway to Pakistan". www.pakistan.gov.pk. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ↑ Kinze, C.C. (2000). "Rehabilitation of Platanista gangetica (Lebeck, 1801) as the valid scientific name of the Ganges dolphin". Zoologische Mededelingen. repository.naturalis.nl. 74: 193–203.

- ↑ Pilleri, G.; G. Marcuzzi & O. Pilleri (1982). "Speciation in the Platanistoidea, systematic, zoogeographical and ecological observations on recent species". Investigations on Cetacea. 14: 15–46.

- ↑ "One Species or Two? Vicariance, Lineage Divergence and Low mtDNA Diversity in Geographically Isolated Populations of South Asian River Dolphin" (PDF). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22(1). 2015. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9265-6.

- ↑ Rice, DW (1998). Marine mammals of the world: Systematics and distribution. Society for Marine Mammalogy. ISBN 978-1891276033.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Khan, M.S. (2013). "Indus River Dolphin: The Survivor of River Beas, Punjab, India". Current Science. 104 (11): 1464–1465.

- ↑ Kasuya, T., 1972. Some information on the growth of the Ganges dolphin with a comment on the Indus dolphin. Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst., 24: 87–108

Further reading

- Randall R. Reeves; Brent S. Stewart; Phillip J. Clapham; James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410.

- Smith, B. D.; G. T. Braulik & R. K. Sinha (2004). "Platanista gangetica gangetica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- Smith, B. D.; G. T. Braulik & A. A. Chaudhry (2004). "Platanista gangetica minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- Blind dolphins need space to breath - The Nation (Pakistan)

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Indus river dolphin |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indus river dolphin. |