War economy

A war economy is the set of contingencies undertaken by a modern state to mobilize its economy for war production. Philippe Le Billon describes a war economy as a "system of producing, mobilizing and allocating resources to sustain the violence." Some measures taken include the increasing of tax rates as well as the introduction of resource allocation programs. Needless to say, every country approaches the reconfiguration of its economy in a different way.

Many states increase the degree of planning in their economies during wars; in many cases this extends to rationing, and in some cases to conscription for civil defenses, such as the Women's Land Army and Bevin Boys in the United Kingdom in World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt said if the Axis Powers win, then "we would have to convert ourselves permanently into a militaristic power on the basis of war economy."[1]

During total war situations, certain buildings and positions are often seen as important targets by combatants. The Union blockade, Union General William T. Sherman's March to the Sea during the American Civil War, and the strategic bombing of enemy cities and factories during World War II are all examples of total war.[2]

Concerning the side of aggregate demand, this concept has been linked to the concept of "military Keynesianism", in which the government's military budget stabilizes business cycles and fluctuations and/or is used to fight recessions.

On the supply side, it has been observed that wars sometimes have the effect of accelerating progress of technology to such an extent that an economy is greatly strengthened after the war, especially if it has avoided the war-related destruction. This was the case, for example, with the United States in World War I and World War II. Some economists (such as Seymour Melman) argue, however, that the wasteful nature of much of military spending eventually can hurt technological progress.

United States

The United States alone has a very complex history with wartime economies. Many notable instances came during the twentieth century in which America’s main conflicts consisted of the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam.

World War I

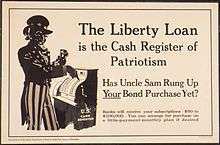

In mobilizing for World War I, the United States expanded its governmental powers by creating institutions such as the War Industries Board (WIB) to help with military production.[3] Others, such as the Fuel Administration, introduced daylight saving time in an effort to save coal and oil while the Food Administration encouraged higher grain production and “mobilized a spirit of self-sacrifice rather than mandatory rationing.”[3] Propaganda also played a large part in garnering support for topics ranging from tax initiatives to food conservation. Speaking on Four Minute Men, volunteers who rallied the public through short speeches, investigative journalist George Creel stated that the idea was extremely popular and the program saw thousands of volunteers throughout the states.[4]

World War II

In the case of the Second World War, the U.S. government took similar measures in increasing its control over the economy. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor provided the spark needed to begin conversion to a wartime economy. With this attack, Washington felt that a greater bureaucracy was needed to help with mobilization.[5] The government raised taxes which paid for half of the war’s costs and borrowed money in the form of war bonds to cover the rest of the bill.[3] “Commercial institutions like banks also bought billions of dollars of bonds and other treasury paper, holding more than $24 billion at the war’s end."[5] The creation of a handful of agencies helped funnel resources towards the war effort. One prominent agency was the War Productions board (WPB), which “awarded defense contracts, allocated scarce resources – such as rubber, copper, and oil – for military uses, and persuaded businesses to convert to military production."[3] Two-thirds of the American economy had been integrated into the war effort by the end of 1943.[3] Because of this massive cooperation between government and private entities, it could be argued that the economic measures enacted prior to and during the Second World War helped lead the Allies to victory.

Germany

World War I

Germany has experienced economic devastation following both World Wars. While this was not a result of faulty economic planning, it is important to understand the ways that Germany approached reconstruction. In World War I, the German agricultural sector was hit hard by the demands of the war effort. Not only were many of the workers conscripted, but lots of the food itself was allocated for the troops leading to a shortage.[6] “German authorities were not able to solve the food scarcity [problem], but implemented a food rationing system and several price ceilings to prevent speculation and profiteering. Unfortunately, these measures did not have the desired success."[6]

World War II

Heading into the Second World War, the Nazis introduced new policies that not only caused the unemployment rate to drop, it created a competent war machine in clear violation of the Treaty of Versailles. The Third Reich implemented a draft and built factories to supply its quickly expanding military. Both of these actions created jobs for many Germans who had been struggling from the economic collapse following World War I.[7] However, it is worth noting that while unemployment rates plummeted, “by 1939, government debt stood at over 40 billion Reichsmarks."[7] After World War II, Germany was discovered to have exploited the economies of the countries it invaded. The most important among these, according to historians Boldorf and Scherner, was France and “her highly developed economy… [being] one of the biggest in Europe.”[8] This is further supported when they later reveal how the French economy provided for 11 percent of Germany’s national income (during the occupation) which covered five months of Germany’s total income for the war. Using extortion and forced labor, the Nazis siphoned off much of France's economic output. For example, during the early months of the Nazi occupation, the French puppet government was forced to pay a "quartering" fee of twenty million Reichmarks per day. Supposedly, the fee was payment for the Nazi occupation forces. In reality, the money was used to fuel the Nazi war economy.[8] Germany employed numerous methods to support its war effort. However, due to the Nazi’s surrender to the Allies, it is hard to tell what their economic policies would have yielded in the long term.

See also

- Economic warfare

- Industrial warfare

- Military-industrial complex

- Companies by arms sales

- Total war

- War communism

- War effort

Further reading

- Moeller, Susan. (1999). "Compassion Fatigue", Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sells Disease, Famine, War and Death. New York & London: Routledge. 6 - 53.

- Goldstein, Joshua S. (2001). War and gender: How gender shapes the war system and vice versa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Le Billon, Dr. Philippe (2005) Geopolitics of Resource Wars: Resource Dependence, Governance and Violence. London: Frank Cass, 288pp

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wartime economy propaganda. |

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. "The Great Arsenal of Democracy".

- ↑ Durham, Robert. "Supplying the Enemy: The Modern Arms Industry & the Military–Industrial Complex". Google Books. Lulu.com, 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Henretta, Edwards, Self, James A., Rebecca, Robert O. (2011). America's History. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 672+.

- ↑ Creel, George (1920). How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe. New York: Harper and Bros. pp. 84–88, 90–92.

- 1 2 Tassava, Christopher. "The American Economy During World War II". EH.net. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- 1 2 Blum, Matthias (December 2011). "Government Decisions Before and During the First World War and the Living Standards in Germany During a Drastic Natural Experiment". Explorations in Economic History. 48 (4): 556–567. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2011.07.003. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- 1 2 Trueman, Chris. "The Nazis and the German Economy". History Learning Site. HistoryLearningSite.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- 1 2 Boldorf, Marcel; Scherner, Jonas (April 2012). "France's Occupation Costs and the War in the East: The Contribution to the German War Economy, 1940-4" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History. 47 (2): 291–316. doi:10.1177/0022009411431711. Retrieved 2012-04-25.