SOSUS

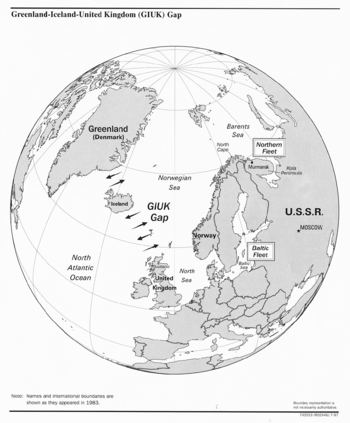

SOSUS, an acronym for sound surveillance system, is a chain of underwater listening posts located around the world in places such as the Atlantic Ocean near Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom—the GIUK gap—and at various locations in the Pacific Ocean. The United States Navy's initial intent for the system was for tracking Soviet submarines, which had to pass through the gap to attack targets further west. It was later supplemented by mobile assets such as the Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS), and became part of the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS).

History

SOSUS development was started in 1949 when the US Navy formed the Committee for Undersea Warfare to research anti-submarine warfare. The panel allocated $10 million annually to develop systems to counter the Soviet submarine threat consisting primarily of a large fleet of diesel submarines. They decided on a system to monitor low-frequency sound in the SOFAR channel using multiple listening sites equipped with hydrophones and a processing facility that could detect submarine positions by triangulation over hundreds of miles.

Research phase

At MIT in 1950, the committee sponsored Project Hartwell, named for the Hartwell Farms restaurant in Lexington, MA, where some of the initial steps were planned.[1] In November, they selected Western Electric to build a demonstration system, and the first six element hydrophone array was installed on the island of Eleuthera in the Bahamas. Meanwhile, Project Jezebel at Bell Labs and Project Michael at Columbia University focused on studying long range acoustics in the ocean.

By 1952, enough progress resulted in top secret plans to deploy six arrays in the North Atlantic basin, and the classified name SOSUS was used. The number of arrays was increased to nine later in the year, and Royal Navy and USN ships, including USS Neptune and USS Peregrine, started laying the cabling under the cover of Project Caesar. In 1953, Jezebel's research had developed an additional high-frequency system for direct plotting of ships passing over the stations, intended to be installed in narrows and straits, called Project Colossus.

SOSUS goes operational

In 1961, SOSUS tracked the Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) submarine USS George Washington (SSBN-598) from the US to the UK. The next year SOSUS detected and tracked its first Soviet diesel submarine. Later that year the SOSUS test system in the Bahamas tracked a Soviet Foxtrot class submarine during the Cuban Missile Crisis. SOSUS was upgraded a number of times as submarines became quieter.

SOSUS systems consisted of bottom mounted hydrophone arrays connected by underwater cables to facilities ashore. The individual arrays were installed primarily on continental slopes and seamounts at locations optimized for undistorted long range acoustic propagation. The combination of location within the ocean and the sensitivity of arrays allowed the system to detect acoustic power of less than a watt at ranges of several hundred kilometres (The system is so sensitive that it can even detect the presence of Soviet/Russian Tu-95 Bear 4-engine bombers flying overhead; the tips of the bombers's long propellers exceed the speed of sound, creating sonic booms as they rotate. These sonic booms reach the surface of the ocean below, which then transmits the sonic shocks to the underwater hydrophones.[2]).

SOSUS monitoring stations were known as Naval Facilities (NAVFAC, not to be confused with the Naval Facilities Engineering Command that has the same acronym.) NAVFACs existed in the west at Naval Air Station Adak, Alaska; Naval Facility Pacific Beach, Washington; Naval Facility Coos Head, Oregon; Naval Facility Centerville Beach near Eel River, California; Naval Facility Point Sur near Monterey, California; Naval Outlying Field San Nicolas Island, California; and Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington.

In the east, they were deployed at the Tom Nevers Naval Facility, Massachusetts; Naval Facility Cape Henlopen/Naval Facility Lewes, Delaware; Naval Facility Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; and Naval Facility Punta Borinquen, Puerto Rico.

Other NAVFACs were located in the Pacific at Naval Air Station Barbers Point, Hawaii; Naval Air Facility Midway; and Naval Base Guam, while additional Atlantic locations expanded to include Naval Air Station Keflavik, Iceland; CFS Shelburne, Nova Scotia and Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland (both later remoted to CFB Halifax, Nova Scotia); Naval Facility Brawdy, Wales; Joint Maritime Facility St. Mawgan, Cornwall; Antigua; Maritime Data Centre Gibraltar, UK; Naval Facility Barbados; Naval Facility Eleuthera, Bahamas; Naval Facility San Salvador, Bahamas; Naval Facility Bermuda; and Naval Facility Grand Turk. Evaluation Centers were also set up at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington and Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia in the early 1980s. The Data Evaluation Center at Dam Neck was named after Commander Will James whose entire Navy career was spent in the system.

When the USS Thresher (SSN-593) sank in 1963, SOSUS helped determine its location. In 1968, the first detections of Victor and Charlie class Soviet submarines were made, while in 1974 the first Delta class submarine was observed. In 1968, SOSUS played a key role in locating the wreckage of a US Nuclear Attack submarine, the USS Scorpion (SSN-589), lost near the Azores in May. Moreover, SOSUS data from March 1968 facilitated the discovery, and clandestine retrieval 6 years later, of parts of a Soviet GOLF II-class ballistic missile submarine, the K-129, that foundered that month north of Hawaii.[3]

In 1985, the Fixed Distributed System (FDS) test array became operational and the first SURTASS patrol began. The name for the overall system had become Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS).

Given its criticality to Cold War operations against the Soviet Navy's submarine fleet, SOSUS / IUSS remained highly classified from its inception and the purpose and activities of the various NAVFACs was not publicly acknowledged nor commonly known outside of the U.S. Navy's submarine fleet, its cruiser/destroyer/frigate fleet, and its antisubmarine warfare aircraft forces until the end of the Cold War. In 1991, the system mission was declassified and the next year it began reporting whale detections and SOSUS work stations began replacing paper lofargrams. The Advanced Deployable System became operational as part of IUSS in 1996.

SOSUS Secrecy Compromised

In 1988, Stephen Joseph Ratkai, a Hungarian-Canadian recruited by Soviet Intelligence, was arrested, charged and convicted in St. John's, Newfoundland for attempting to obtain information on the SOSUS site at Naval Station Argentia. John Anthony Walker, a United States Navy Chief Warrant Officer and communications specialist, divulged SOSUS operational information to the Soviet Union during the Cold War which compromised its effectiveness.[4][5]

SOSUS after the Cold War

SOSUS was gradually condensed into a smaller number of monitoring stations during the 1970s and 1980s. However, the SOSUS arrays themselves were based upon technology that could only be upgraded irregularly. With the ending of the Cold War in the 1990s, the immediate need for SOSUS decreased, and the focus of the US Navy also turned toward a system that was deployable on a theatre basis. In effect, the end of the Cold War eliminated much of the justification for maintaining IUSS at its full capability, with the existence and capabilities of SOSUS and IUSS being declassified in 1991.[3] Although officially declassified in 1991, by that time IUSS and SOSUS had long been an open secret.[3]

Alternate or dual-use partnerships exist with the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory[6] for Ocean Acoustic Tomography, NOAA VENTS,[7] Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute,[8] Texas ARL,[9] and several other organizations.

Commander, Undersea Surveillance (CUS), operates as the immediate superior in command (ISIC) for all IUSS sites, whereas operational command of those same sites is held by Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC).

See also

- Communication with submarines

- Integrated Undersea Surveillance System insignia

- SOFAR channel

- Project Artemis

References

- ↑ This explanation of Hartwell for the name of the project is given in fn. 24 on p. 338 of Jack S. Goldstein's biography of Jerrold Zacharias; A Different Sort of Time.

- ↑ Television interview of Tom Clancy: "I was amazed when I discovered this. I hadn't thought it could be true until I was personally told so by a former SOSUS operator."

- 1 2 3 "SOSUS The "Secret Weapon" of Undersea Surveillance". Undersea Warfare. Vol. 7 no. 2. US Navy. Winter 2005. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/06/us/spy-case-is-called-threat-to-finding-soviet-submarines.html

- ↑ http://www.nps.edu/Academics/Schools/GSEAS/Departments/USW/Documents/HOWARDAPR2011.pdf

- ↑ Blue Water Acoustic Research at APL-UW

- ↑ "NOAA PMEL Acoustics Program". Pmel.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- ↑ "Autonomous Hydrophone Array (AHA)". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 2012-02-03. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- ↑ "Ongoing Research at ARL:UT". Arlut.utexas.edu. University of Texas at Austin Applied Research Laboratories. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

|section=ignored (help)

External links

- History of IUSS: Timeline

- "SOSUS: The 'Secret Weapon' of Undersea Surveillance", Undersea Warfare, Winter, 2005, Vol. 7, No. 2, article by Edward C. Whitman

- The Acoustic Monitoring Project

- The Third Battle: Innovation in the US Navy's Silent Cold War (MIT: March, 2000)

- Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), GlobalSecurity.org

- A Letter from Joe Worzel to Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory regarding the establishment of Palisades Geophysical Institute, its work, and support of the education and research community

- The SOund SUrveillance System, Federation of American Scientists, Intelligence Resource Program

- Navy article on Sosus

- Japanese LQO-3 SOSUS Arrays.