Irreconcilables

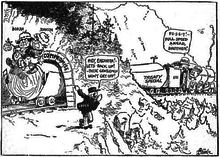

The Irreconcilables were bitter opponents of the Treaty of Versailles in the United States in 1919. Specifically, the term refers to about 12 to 18 United States Senators, both Republicans and Democrats, who fought intensely to defeat the ratification of the treaty by the Senate in 1919. They succeeded, and the United States never ratified the Treaty of Versailles and never joined the League of Nations.

The Republican Party controlled the United States Senate after the election of 1918, but the Senators were divided into multiple positions on the Versailles question. It proved possible to build a majority coalition, but impossible to build a two thirds coalition that was needed to pass a treaty.[1] One block of Democrats strongly supported the Versailles Treaty. A second group of Democrats supported the Treaty but followed President Woodrow Wilson in opposing any amendments or reservations. The largest bloc, led by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge,[2] comprised a majority of the Republicans. They wanted a treaty with reservations, especially on Article 10, which involved the power of the League Nations to make war without a vote by the United States Congress.[3] The closest the Treaty came to passage, came in mid-November 1919, was when Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-Treaty Democrats, and were close to a two-thirds majority for a Treaty with reservations, but Wilson rejected this compromise and enough Democrats followed his lead to permanently end the chances for ratification.

Among the leading Irreconcilables were Republicans George Norris of Nebraska, William Borah of Idaho, Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, and Hiram Johnson of California. Democrats included Senators Thomas Gore of Oklahoma, James Reed of Missouri, and the Irish Catholic leader David I. Walsh of Massachusetts.[4]

The lists vary, but Ralph Stone identified sixteen in 1963: William Borah of Idaho, Frank B. Brandegee of Connecticut, Albert B. Fall of New Mexico, Bert M. Fernald of Maine, Joseph I. France of Maryland, Asle J. Gronna of North Dakota, Hiram W. Johnson of California, Philander C. Knox of Pennsylvania, Robert M. LaFollette of Wisconsin, Medill McCormick of Illinois, George H. Moses of New Hampshire, George W. Norris of Nebraska, Miles Poindexter of Washington, James A. Reed of Missouri, Lawrence Sherman of Illinois, and Charles S. Thomas of Colorado. Reed and Thomas were Democrats, the other 14 were Republicans

McCormick's position can be traced to his Anglophobia and nationalistic attitudes, Sherman's to personal antipathy to President Woodrow Wilson and his domestic policies.[5] Indeed, all of the Irreconcilables were bitter enemies of President Wilson, and he launched a nationwide speaking tour in the summer of 1919 to refute them. However, Wilson collapsed midway with a serious stroke that effectively ruined his leadership skills.[6]

According to Stone's 1970 book, the Irreconcilables in the Senate fell into three loosely defined factions. One group was composed of isolationists and extreme nationalists who proclaimed that America must be the sole commander of its destiny, and that membership in any international organization that might have power over the United States was unacceptable. A second group, the "realists", rejected narrow isolationism in favor of limited cooperation among nations with similar interests. They thought the League of Nations would be too strong. A third group, the "idealists", called for a truly democratic league to foster peace and justice in the world. The three factions cooperated to help defeat the treaty. All of them denounced the League as a tool of Britain and its nefarious empire.

Among the American public as a whole, the Irish Catholics and the German Americans were intensely opposed to the Treaty.[7]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Thomas A. Bailey, Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945)

- ↑ William C. Widenor, Henry Cabot Lodge and the Search for an American Foreign Policy (1980)

- ↑ Stone (1970)

- ↑ Bailey, (1945) p. 53.

- ↑ Stone 1963

- ↑ John Milton Cooper, Jr. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009) ch 22

- ↑ Duff (1968)

Further reading

- Bailey, Thomas A. Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945)

- Duff, John B. "The Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans," Journal of American History Vol. 55, No. 3 (Dec., 1968), pp. 582–598 in JSTOR

- Stone, Ralph A. The Irreconcilables: The Fight Against the League of Nations. (University Press of Kentucky, 1970)

- Stone, Ralph A. "The Irreconcilables' Alternatives to the League," Mid America, 1967, Vol. 49 Issue 3, pp 163–173,

- Stone, Ralph A. "Two Illinois Senators among the Irreconcilables," Mississippi Valley Historical Review Vol. 50, No. 3 (Dec., 1963), pp. 443–465 in JSTOR

- Stone, Ralph A. ed. Wilson and the League of Nations (1967), articles by scholars.