Computer security

| This article is part of a series on |

| Computer security |

|---|

|

| Related security categories |

| Threats |

| Defenses |

Computer security, also known as cyber security or IT security, is the protection of computer systems from the theft or damage to the hardware, software or the information on them, as well as from disruption or misdirection of the services they provide.[1]

It includes controlling physical access to the hardware, as well as protecting against harm that may come via network access, data and code injection,[2] and due to malpractice by operators, whether intentional, accidental, or due to them being tricked into deviating from secure procedures.[3]

The field is of growing importance due to the increasing reliance on computer systems and the Internet in most societies,[4] wireless networks such as Bluetooth and Wi-Fi – and the growth of "smart" devices, including smartphones, televisions and tiny devices as part of the Internet of Things.

Vulnerabilities and attacks

A vulnerability is a system susceptibility or flaw. Many vulnerabilities are documented in the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database. An exploitable vulnerability is one for which at least one working attack or "exploit" exists.[5]

To secure a computer system, it is important to understand the attacks that can be made against it, and these threats can typically be classified into one of the categories below:

Backdoors

A backdoor in a computer system, a cryptosystem or an algorithm, is any secret method of bypassing normal authentication or security controls. They may exist for a number of reasons, including by original design or from poor configuration. They may have been added by an authorized party to allow some legitimate access, or by an attacker for malicious reasons; but regardless of the motives for their existence, they create a vulnerability.

Denial-of-service attack

Denial of service attacks (DoS) are designed to make a machine or network resource unavailable to its intended users.[6] Attackers can deny service to individual victims, such as by deliberately entering a wrong password enough consecutive times to cause the victim account to be locked, or they may overload the capabilities of a machine or network and block all users at once. While a network attack from a single IP address can be blocked by adding a new firewall rule, many forms of Distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks are possible, where the attack comes from a large number of points – and defending is much more difficult. Such attacks can originate from the zombie computers of a botnet, but a range of other techniques are possible including reflection and amplification attacks, where innocent systems are fooled into sending traffic to the victim.

Direct-access attacks

An unauthorized user gaining physical access to a computer is most likely able to directly copy data from it. They may also compromise security by making operating system modifications, installing software worms, keyloggers, covert listening devices or using wireless mice.[7] Even when the system is protected by standard security measures, these may be able to be by-passed by booting another operating system or tool from a CD-ROM or other bootable media. Disk encryption and Trusted Platform Module are designed to prevent these attacks.

Eavesdropping

Eavesdropping is the act of surreptitiously listening to a private conversation, typically between hosts on a network. For instance, programs such as Carnivore and NarusInsight have been used by the FBI and NSA to eavesdrop on the systems of internet service providers. Even machines that operate as a closed system (i.e., with no contact to the outside world) can be eavesdropped upon via monitoring the faint electro-magnetic transmissions generated by the hardware; TEMPEST is a specification by the NSA referring to these attacks.

Spoofing

Spoofing, in general, is a fraudulent or malicious practice in which communication is sent from an unknown source disguised as a source known to the receiver. Spoofing is most prevalent in communication mechanisms that lack a high level of security.[8]

Tampering

Tampering describes a malicious modification of products. So-called "Evil Maid" attacks and security services planting of surveillance capability into routers[9] are examples.

Privilege escalation

Privilege escalation describes a situation where an attacker with some level of restricted access is able to, without authorization, elevate their privileges or access level. So for example a standard computer user may be able to fool the system into giving them access to restricted data; or even to "become root" and have full unrestricted access to a system.

Phishing

Phishing is the attempt to acquire sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details directly from users.[10] Phishing is typically carried out by email spoofing or instant messaging, and it often directs users to enter details at a fake website whose look and feel are almost identical to the legitimate one. Preying on a victim's trust, phishing can be classified as a form of social engineering.

Clickjacking

Clickjacking, also known as "UI redress attack" or "User Interface redress attack", is a malicious technique in which an attacker tricks a user into clicking on a button or link on another webpage while the user intended to click on the top level page. This is done using multiple transparent or opaque layers. The attacker is basically "hijacking" the clicks meant for the top level page and routing them to some other irrelevant page, most likely owned by someone else. A similar technique can be used to hijack keystrokes. Carefully drafting a combination of stylesheets, iframes, buttons and text boxes, a user can be led into believing that they are typing the password or other information on some authentic webpage while it is being channeled into an invisible frame controlled by the attacker.

Social engineering

Social engineering aims to convince a user to disclose secrets such as passwords, card numbers, etc. by, for example, impersonating a bank, a contractor, or a customer.[11]

A popular and profitable cyber scam involves fake CEO emails sent to accounting and finance departments. In early 2016, the FBI reported that the scam has cost US businesses more than $2bn in about two years.[12]

In May 2016, the Milwaukee Bucks NBA team was the victim of this type of cyber scam with a perpetrator impersonating the team's president Peter Feigin, resulting in the handover of all the team's employees' 2015 W-2 tax forms.[13]

Systems at risk

Computer security is critical in almost any industry which uses computers. Currently, most electronic devices such as computers, laptops and cellphones come with built in firewall security software, but despite this, computers are not 100 percent accurate and dependable to protect our data (Smith, Grabosky & Urbas, 2004.) There are many different ways of hacking into computers. It can be done through a network system, clicking into unknown links, connecting to unfamiliar Wi-Fi, downloading software and files from unsafe sites, power consumption, electromagnetic radiation waves, and many more. However, computers can be protected through well built software and hardware. By having strong internal interactions of properties, software complexity can prevent software crash and security failure.[14]

Financial systems

Web sites and apps that accept or store credit card numbers, brokerage accounts, and bank account information are prominent hacking targets, because of the potential for immediate financial gain from transferring money, making purchases, or selling the information on the black market.[15] In-store payment systems and ATMs have also been tampered with in order to gather customer account data and PINs.

Utilities and industrial equipment

Computers control functions at many utilities, including coordination of telecommunications, the power grid, nuclear power plants, and valve opening and closing in water and gas networks. The Internet is a potential attack vector for such machines if connected, but the Stuxnet worm demonstrated that even equipment controlled by computers not connected to the Internet can be vulnerable to physical damage caused by malicious commands sent to industrial equipment (in that case uranium enrichment centrifuges) which are infected via removable media. In 2014, the Computer Emergency Readiness Team, a division of the Department of Homeland Security, investigated 79 hacking incidents at energy companies.[16] Vulnerabilities in smart meters (many of which use local radio or cellular communications) can cause problems with billing fraud.[17]

Aviation

The aviation industry is very reliant on a series of complex system which could be attacked.[18] A simple power outage at one airport can cause repercussions worldwide,[19] much of the system relies on radio transmissions which could be disrupted,[20] and controlling aircraft over oceans is especially dangerous because radar surveillance only extends 175 to 225 miles offshore.[21] There is also potential for attack from within an aircraft.[22]

In Europe, with the (Pan-European Network Service)[23] and NewPENS,[24] and in the US with the NextGen program,[25] air navigation service providers are moving to create their own dedicated networks.

The consequences of a successful attack range from loss of confidentiality to loss of system integrity, which may lead to more serious concerns such as exfiltration of data, network and air traffic control outages, which in turn can lead to airport closures, loss of aircraft, loss of passenger life, damages on the ground and to transportation infrastructure. A successful attack on a military aviation system that controls munitions could have even more serious consequences.

Consumer devices

Desktop computers and laptops are commonly infected with malware either to gather passwords or financial account information, or to construct a botnet to attack another target. Smart phones, tablet computers, smart watches, and other mobile devices such as Quantified Self devices like activity trackers have also become targets and many of these have sensors such as cameras, microphones, GPS receivers, compasses, and accelerometers which could be exploited, and may collect personal information, including sensitive health information. Wifi, Bluetooth, and cell phone networks on any of these devices could be used as attack vectors, and sensors might be remotely activated after a successful breach.[26]

Home automation devices such as the Nest thermostat are also potential targets.[26]

Large corporations

Large corporations are common targets. In many cases this is aimed at financial gain through identity theft and involves data breaches such as the loss of millions of clients' credit card details by Home Depot,[27] Staples,[28] and Target Corporation.[29] Medical records have been targeted for use in general identify theft, health insurance fraud, and impersonating patients to obtain prescription drugs for recreational purposes or resale.[30]

Not all attacks are financially motivated however; for example security firm HBGary Federal suffered a serious series of attacks in 2011 from hacktivist group Anonymous in retaliation for the firm's CEO claiming to have infiltrated their group, [31][32] and Sony Pictures was attacked in 2014 where the motive appears to have been to embarrass with data leaks, and cripple the company by wiping workstations and servers.[33][34]

Automobiles

If access is gained to a car's internal controller area network, it is possible to disable the brakes and turn the steering wheel.[35] Computerized engine timing, cruise control, anti-lock brakes, seat belt tensioners, door locks, airbags and advanced driver assistance systems make these disruptions possible, and self-driving cars go even further. Connected cars may use wifi and bluetooth to communicate with onboard consumer devices, and the cell phone network to contact concierge and emergency assistance services or get navigational or entertainment information; each of these networks is a potential entry point for malware or an attacker.[35] Researchers in 2011 were even able to use a malicious compact disc in a car's stereo system as a successful attack vector,[36] and cars with built-in voice recognition or remote assistance features have onboard microphones which could be used for eavesdropping.

A 2015 report by U.S. Senator Edward Markey criticized manufacturers' security measures as inadequate, and also highlighted privacy concerns about driving, location, and diagnostic data being collected, which is vulnerable to abuse by both manufacturers and hackers.[37]

Government

Government and military computer systems are commonly attacked by activists[38][39][40][41] and foreign powers.[42][43][44][45] Local and regional government infrastructure such as traffic light controls, police and intelligence agency communications, personnel records, student records,[46] and financial systems are also potential targets as they are now all largely computerized. Passports and government ID cards that control access to facilities which use RFID can be vulnerable to cloning.

Internet of Things and physical vulnerabilities

The Internet of Things (IoT) is the network of physical objects such as devices, vehicles, and buildings that are embedded with electronics, software, sensors, and network connectivity that enables them to collect and exchange data[47] – and concerns have been raised that this is being developed without appropriate consideration of the security challenges involved.[48][49]

While the IoT creates opportunities for more direct integration of the physical world into computer-based systems,[50][51] it also provides opportunities for misuse. In particular, as the Internet of Things spreads widely, cyber attacks are likely to become an increasingly physical (rather than simply virtual) threat.[52] If a front door's lock is connected to the Internet, and can be locked/unlocked from a phone, then a criminal could enter the home at the press of a button from a stolen or hacked phone. People could stand to lose much more than their credit card numbers in a world controlled by IoT-enabled devices. Thieves have also used electronic means to circumvent non-Internet-connected hotel door locks.[53]

Medical devices have either been successfully attacked or had potentially deadly vulnerabilities demonstrated, including both in-hospital diagnostic equipment[54] and implanted devices including pacemakers[55] and insulin pumps.[56]

Impact of security breaches

Serious financial damage has been caused by security breaches, but because there is no standard model for estimating the cost of an incident, the only data available is that which is made public by the organizations involved. "Several computer security consulting firms produce estimates of total worldwide losses attributable to virus and worm attacks and to hostile digital acts in general. The 2003 loss estimates by these firms range from $13 billion (worms and viruses only) to $226 billion (for all forms of covert attacks). The reliability of these estimates is often challenged; the underlying methodology is basically anecdotal."[57]

However, reasonable estimates of the financial cost of security breaches can actually help organizations make rational investment decisions. According to the classic Gordon-Loeb Model analyzing the optimal investment level in information security, one can conclude that the amount a firm spends to protect information should generally be only a small fraction of the expected loss (i.e., the expected value of the loss resulting from a cyber/information security breach).[58]

Attacker motivation

As with physical security, the motivations for breaches of computer security vary between attackers. Some are thrill-seekers or vandals, others are activists or criminals looking for financial gain. State-sponsored attackers are now common and well resourced, but started with amateurs such as Markus Hess who hacked for the KGB, as recounted by Clifford Stoll, in The Cuckoo's Egg.

A standard part of threat modelling for any particular system is to identify what might motivate an attack on that system, and who might be motivated to breach it. The level and detail of precautions will vary depending on the system to be secured. A home personal computer, bank, and classified military network face very different threats, even when the underlying technologies in use are similar.

Computer protection (countermeasures)

In computer security a countermeasure is an action, device, procedure, or technique that reduces a threat, a vulnerability, or an attack by eliminating or preventing it, by minimizing the harm it can cause, or by discovering and reporting it so that corrective action can be taken.[59][60][61]

Some common countermeasures are listed in the following sections:

Security by design

Security by design, or alternately secure by design, means that the software has been designed from the ground up to be secure. In this case, security is considered as a main feature.

Some of the techniques in this approach include:

- The principle of least privilege, where each part of the system has only the privileges that are needed for its function. That way even if an attacker gains access to that part, they have only limited access to the whole system.

- Automated theorem proving to prove the correctness of crucial software subsystems.

- Code reviews and unit testing, approaches to make modules more secure where formal correctness proofs are not possible.

- Defense in depth, where the design is such that more than one subsystem needs to be violated to compromise the integrity of the system and the information it holds.

- Default secure settings, and design to "fail secure" rather than "fail insecure" (see fail-safe for the equivalent in safety engineering). Ideally, a secure system should require a deliberate, conscious, knowledgeable and free decision on the part of legitimate authorities in order to make it insecure.

- Audit trails tracking system activity, so that when a security breach occurs, the mechanism and extent of the breach can be determined. Storing audit trails remotely, where they can only be appended to, can keep intruders from covering their tracks.

- Full disclosure of all vulnerabilities, to ensure that the "window of vulnerability" is kept as short as possible when bugs are discovered.

Security architecture

The Open Security Architecture organization defines IT security architecture as "the design artifacts that describe how the security controls (security countermeasures) are positioned, and how they relate to the overall information technology architecture. These controls serve the purpose to maintain the system's quality attributes: confidentiality, integrity, availability, accountability and assurance services".[62]

Techopedia defines security architecture as "a unified security design that addresses the necessities and potential risks involved in a certain scenario or environment. It also specifies when and where to apply security controls. The design process is generally reproducible." The key attributes of security architecture are:[63]

- the relationship of different components and how they depend on each other.

- the determination of controls based on risk assessment, good practice, finances, and legal matters.

- the standardization of controls.

Security measures

A state of computer "security" is the conceptual ideal, attained by the use of the three processes: threat prevention, detection, and response. These processes are based on various policies and system components, which include the following:

- User account access controls and cryptography can protect systems files and data, respectively.

- Firewalls are by far the most common prevention systems from a network security perspective as they can (if properly configured) shield access to internal network services, and block certain kinds of attacks through packet filtering. Firewalls can be both hardware- or software-based.

- Intrusion Detection System (IDS) products are designed to detect network attacks in-progress and assist in post-attack forensics, while audit trails and logs serve a similar function for individual systems.

- "Response" is necessarily defined by the assessed security requirements of an individual system and may cover the range from simple upgrade of protections to notification of legal authorities, counter-attacks, and the like. In some special cases, a complete destruction of the compromised system is favored, as it may happen that not all the compromised resources are detected.

Today, computer security comprises mainly "preventive" measures, like firewalls or an exit procedure. A firewall can be defined as a way of filtering network data between a host or a network and another network, such as the Internet, and can be implemented as software running on the machine, hooking into the network stack (or, in the case of most UNIX-based operating systems such as Linux, built into the operating system kernel) to provide real time filtering and blocking. Another implementation is a so-called "physical firewall", which consists of a separate machine filtering network traffic. Firewalls are common amongst machines that are permanently connected to the Internet.

Some organizations are turning to big data platforms, such as Apache Hadoop, to extend data accessibility and machine learning to detect advanced persistent threats.[64][65]

However, relatively few organisations maintain computer systems with effective detection systems, and fewer still have organised response mechanisms in place. As result, as Reuters points out: "Companies for the first time report they are losing more through electronic theft of data than physical stealing of assets".[66] The primary obstacle to effective eradication of cyber crime could be traced to excessive reliance on firewalls and other automated "detection" systems. Yet it is basic evidence gathering by using packet capture appliances that puts criminals behind bars.

Vulnerability management

Vulnerability management is the cycle of identifying, and remediating or mitigating vulnerabilities",[67] especially in software and firmware. Vulnerability management is integral to computer security and network security.

Vulnerabilities can be discovered with a vulnerability scanner, which analyzes a computer system in search of known vulnerabilities,[68] such as open ports, insecure software configuration, and susceptibility to malware

Beyond vulnerability scanning, many organisations contract outside security auditors to run regular penetration tests against their systems to identify vulnerabilities. In some sectors this is a contractual requirement.[69]

Reducing vulnerabilities

While formal verification of the correctness of computer systems is possible,[70][71] it is not yet common. Operating systems formally verified include seL4,[72] and SYSGO's PikeOS[73][74] – but these make up a very small percentage of the market.

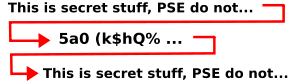

Cryptography properly implemented is now virtually impossible to directly break. Breaking them requires some non-cryptographic input, such as a stolen key, stolen plaintext (at either end of the transmission), or some other extra cryptanalytic information.

Two factor authentication is a method for mitigating unauthorized access to a system or sensitive information. It requires "something you know"; a password or PIN, and "something you have"; a card, dongle, cellphone, or other piece of hardware. This increases security as an unauthorized person needs both of these to gain access.

Social engineering and direct computer access (physical) attacks can only be prevented by non-computer means, which can be difficult to enforce, relative to the sensitivity of the information. Training is often involved to help mitigate this risk,[75][76] but even in a highly disciplined environments (e.g. military organizations), social engineering attacks can still be difficult to foresee and prevent.

It is possible to reduce an attacker's chances by keeping systems up to date with security patches and updates, using a security scanner or/and hiring competent people responsible for security. The effects of data loss/damage can be reduced by careful backing up and insurance.

Hardware protection mechanisms

While hardware may be a source of insecurity, such as with microchip vulnerabilities maliciously introduced during the manufacturing process,[77][78] hardware-based or assisted computer security also offers an alternative to software-only computer security. Using devices and methods such as dongles, trusted platform modules, intrusion-aware cases, drive locks, disabling USB ports, and mobile-enabled access may be considered more secure due to the physical access (or sophisticated backdoor access) required in order to be compromised. Each of these is covered in more detail below.

- USB dongles are typically used in software licensing schemes to unlock software capabilities,[79] but they can also be seen as a way to prevent unauthorized access to a computer or other device's software. The dongle, or key, essentially creates a secure encrypted tunnel between the software application and the key. The principle is that an encryption scheme on the dongle, such as Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) provides a stronger measure of security, since it is harder to hack and replicate the dongle than to simply copy the native software to another machine and use it. Another security application for dongles is to use them for accessing web-based content such as cloud software or Virtual Private Networks (VPNs).[80] In addition, a USB dongle can be configured to lock or unlock a computer.[81]

- Trusted platform modules (TPMs) secure devices by integrating cryptographic capabilities onto access devices, through the use of microprocessors, or so-called computers-on-a-chip. TPMs used in conjunction with server-side software offer a way to detect and authenticate hardware devices, preventing unauthorized network and data access.[82]

- Computer case intrusion detection refers to a push-button switch which is triggered when a computer case is opened. The firmware or BIOS is programmed to show an alert to the operator when the computer is booted up the next time.

- Drive locks are essentially software tools to encrypt hard drives, making them inaccessible to thieves.[83] Tools exist specifically for encrypting external drives as well.[84]

- Disabling USB ports is a security option for preventing unauthorized and malicious access to an otherwise secure computer. Infected USB dongles connected to a network from a computer inside the firewall are considered by the magazine Network World as the most common hardware threat facing computer networks.[85]

- Mobile-enabled access devices are growing in popularity due to the ubiquitous nature of cell phones. Built-in capabilities such as Bluetooth, the newer Bluetooth low energy (LE), Near field communication (NFC) on non-iOS devices and biometric validation such as thumb print readers, as well as QR code reader software designed for mobile devices, offer new, secure ways for mobile phones to connect to access control systems. These control systems provide computer security and can also be used for controlling access to secure buildings.[86]

Secure operating systems

One use of the term "computer security" refers to technology that is used to implement secure operating systems. In the 1980s the United States Department of Defense (DoD) used the "Orange Book"[87] standards, but the current international standard ISO/IEC 15408, "Common Criteria" defines a number of progressively more stringent Evaluation Assurance Levels. Many common operating systems meet the EAL4 standard of being "Methodically Designed, Tested and Reviewed", but the formal verification required for the highest levels means that they are uncommon. An example of an EAL6 ("Semiformally Verified Design and Tested") system is Integrity-178B, which is used in the Airbus A380[88] and several military jets.[89]

Secure coding

In software engineering, secure coding aims to guard against the accidental introduction of security vulnerabilities. It is also possible to create software designed from the ground up to be secure. Such systems are "secure by design". Beyond this, formal verification aims to prove the correctness of the algorithms underlying a system;[90] important for cryptographic protocols for example.

Capabilities and access control lists

Within computer systems, two of many security models capable of enforcing privilege separation are access control lists (ACLs) and capability-based security. Using ACLs to confine programs has been proven to be insecure in many situations, such as if the host computer can be tricked into indirectly allowing restricted file access, an issue known as the confused deputy problem. It has also been shown that the promise of ACLs of giving access to an object to only one person can never be guaranteed in practice. Both of these problems are resolved by capabilities. This does not mean practical flaws exist in all ACL-based systems, but only that the designers of certain utilities must take responsibility to ensure that they do not introduce flaws.

Capabilities have been mostly restricted to research operating systems, while commercial OSs still use ACLs. Capabilities can, however, also be implemented at the language level, leading to a style of programming that is essentially a refinement of standard object-oriented design. An open source project in the area is the E language.

The most secure computers are those not connected to the Internet and shielded from any interference. In the real world, the most secure systems are operating systems where security is not an add-on.

Response to breaches

Responding forcefully to attempted security breaches (in the manner that one would for attempted physical security breaches) is often very difficult for a variety of reasons:

- Identifying attackers is difficult, as they are often in a different jurisdiction to the systems they attempt to breach, and operate through proxies, temporary anonymous dial-up accounts, wireless connections, and other anonymising procedures which make backtracing difficult and are often located in yet another jurisdiction. If they successfully breach security, they are often able to delete logs to cover their tracks.

- The sheer number of attempted attacks is so large that organisations cannot spend time pursuing each attacker (a typical home user with a permanent (e.g., cable modem) connection will be attacked at least several times per day, so more attractive targets could be presumed to see many more). Note however, that most of the sheer bulk of these attacks are made by automated vulnerability scanners and computer worms.

- Law enforcement officers are often unfamiliar with information technology, and so lack the skills and interest in pursuing attackers. There are also budgetary constraints. It has been argued that the high cost of technology, such as DNA testing, and improved forensics mean less money for other kinds of law enforcement, so the overall rate of criminals not getting dealt with goes up as the cost of the technology increases. In addition, the identification of attackers across a network may require logs from various points in the network and in many countries, the release of these records to law enforcement (with the exception of being voluntarily surrendered by a network administrator or a system administrator) requires a search warrant and, depending on the circumstances, the legal proceedings required can be drawn out to the point where the records are either regularly destroyed, or the information is no longer relevant.

Notable attacks and breaches

Some illustrative examples of different types of computer security breaches are given below.

Robert Morris and the first computer worm

In 1988, only 60,000 computers were connected to the Internet, and most were mainframes, minicomputers and professional workstations. On November 2, 1988, many started to slow down, because they were running a malicious code that demanded processor time and that spread itself to other computers – the first internet "computer worm".[91] The software was traced back to 23-year-old Cornell University graduate student Robert Tappan Morris, Jr. who said 'he wanted to count how many machines were connected to the Internet'.[91]

Rome Laboratory

In 1994, over a hundred intrusions were made by unidentified crackers into the Rome Laboratory, the US Air Force's main command and research facility. Using trojan horses, hackers were able to obtain unrestricted access to Rome's networking systems and remove traces of their activities. The intruders were able to obtain classified files, such as air tasking order systems data and furthermore able to penetrate connected networks of National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Goddard Space Flight Center, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, some Defense contractors, and other private sector organizations, by posing as a trusted Rome center user.[92]

TJX customer credit card details

In early 2007, American apparel and home goods company TJX announced that it was the victim of an unauthorized computer systems intrusion[93] and that the hackers had accessed a system that stored data on credit card, debit card, check, and merchandise return transactions.[94]

Stuxnet attack

The computer worm known as Stuxnet reportedly ruined almost one-fifth of Iran's nuclear centrifuges[95] by disrupting industrial programmable logic controllers (PLCs) in a targeted attack generally believed to have been launched by Israel and the United States[96][97][98][99] although neither has publicly acknowledged this.

Global surveillance disclosures

In early 2013, massive breaches of computer security by the NSA were revealed, including deliberately inserting a backdoor in a NIST standard for encryption[100] and tapping the links between Google's data centres.[101] These were disclosed by NSA contractor Edward Snowden.[102]

Target and Home Depot breaches

In 2013 and 2014, a Russian/Ukrainian hacking ring known as "Rescator" broke into Target Corporation computers in 2013, stealing roughly 40 million credit cards,[103] and then Home Depot computers in 2014, stealing between 53 and 56 million credit card numbers.[104] Warnings were delivered at both corporations, but ignored; physical security breaches using self checkout machines are believed to have played a large role. "The malware utilized is absolutely unsophisticated and uninteresting," says Jim Walter, director of threat intelligence operations at security technology company McAfee – meaning that the heists could have easily been stopped by existing antivirus software had administrators responded to the warnings. The size of the thefts has resulted in major attention from state and Federal United States authorities and the investigation is ongoing.

Ashley Madison breach

In July 2015, a hacker group known as "The Impact Team" successfully breached the extramarital relationship website Ashley Madison. The group claimed that they had taken not only company data but user data as well. After the breach, The Impact Team dumped emails from the company's CEO, to prove their point, and threatened to dump customer data unless the website was taken down permanently. With this initial data release, the group stated "Avid Life Media has been instructed to take Ashley Madison and Established Men offline permanently in all forms, or we will release all customer records, including profiles with all the customers' secret sexual fantasies and matching credit card transactions, real names and addresses, and employee documents and emails. The other websites may stay online."[105] When Avid Life Media, the parent company that created the Ashley Madison website, did not take the site offline, The Impact Group released two more compressed files, one 9.7GB and the second 20GB. After the second data dump, Avid Life Media CEO Noel Biderman resigned, but the website remained functional.

Legal issues and global regulation

Conflict of laws in cyberspace has become a major cause of concern for computer security community. Some of the main challenges and complaints about the antivirus industry are the lack of global web regulations, a global base of common rules to judge, and eventually punish, cyber crimes and cyber criminals. There is no global cyber law and cybersecurity treaty that can be invoked for enforcing global cybersecurity issues.

International legal issues of cyber attacks are complicated in nature. Even if an antivirus firm locates the cyber criminal behind the creation of a particular virus or piece of malware or form of cyber attack, often the local authorities cannot take action due to lack of laws under which to prosecute.[106][107] Authorship attribution for cyber crimes and cyber attacks is a major problem for all law enforcement agencies.

"[Computer viruses] switch from one country to another, from one jurisdiction to another – moving around the world, using the fact that we don't have the capability to globally police operations like this. So the Internet is as if someone [had] given free plane tickets to all the online criminals of the world."[106] Use of dynamic DNS, fast flux and bullet proof servers have added own complexities to this situation.

Government

The role of the government is to make regulations to force companies and organizations to protect their systems, infrastructure and information from any cyber-attacks, but also to protect its own national infrastructure such as the national power-grid.[108]

The question of whether the government should intervene or not in the regulation of the cyberspace is a very polemical one. Indeed, for as long as it has existed and by definition, the cyberspace is a virtual space free of any government intervention. Where everyone agree that an improvement on cybersecurity is more than vital, is the government the best actor to solve this issue? Many government officials and experts think that the government should step in and that there is a crucial need for regulation, mainly due to the failure of the private sector to solve efficiently the cybersecurity problem. R. Clarke said during a panel discussion at the RSA Security Conference in San Francisco, he believes that the "industry only responds when you threaten regulation. If industry doesn't respond (to the threat), you have to follow through."[109] On the other hand, executives from the private sector agree that improvements are necessary, but think that the government intervention would affect their ability to innovate efficiently.

Actions and teams in the US

Legislation

The 1986 18 U.S.C. § 1030, more commonly known as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is the key legislation. It prohibits unauthorized access or damage of "protected computers" as defined in .

Although various other measures have been proposed, such as the "Cybersecurity Act of 2010 – S. 773" in 2009, the "International Cybercrime Reporting and Cooperation Act – H.R.4962"[110] and "Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act of 2010 – S.3480"[111] in 2010 – none of these has succeeded.

Executive order 13636 Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity was signed February 12, 2013.

Agencies

The Department of Homeland Security has a dedicated division responsible for the response system, risk management program and requirements for cybersecurity in the United States called the National Cyber Security Division.[112][113] The division is home to US-CERT operations and the National Cyber Alert System.[113] The National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center brings together government organizations responsible for protecting computer networks and networked infrastructure.[114]

The third priority of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is to: "Protect the United States against cyber-based attacks and high-technology crimes",[115] and they, along with the National White Collar Crime Center (NW3C), and the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) are part of the multi-agency task force, The Internet Crime Complaint Center, also known as IC3.[116]

In addition to its own specific duties, the FBI participates alongside non-profit organizations such as InfraGard.[117][118]

In the criminal division of the United States Department of Justice operates a section called the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section. The CCIPS is in charge of investigating computer crime and intellectual property crime and is specialized in the search and seizure of digital evidence in computers and networks.[119]

The United States Cyber Command, also known as USCYBERCOM, is tasked with the defense of specified Department of Defense information networks and "ensure US/Allied freedom of action in cyberspace and deny the same to our adversaries."[120] It has no role in the protection of civilian networks.[121][122]

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission's role in cybersecurity is to strengthen the protection of critical communications infrastructure, to assist in maintaining the reliability of networks during disasters, to aid in swift recovery after, and to ensure that first responders have access to effective communications services.[123]

The Food and Drug Administration has issued guidance for medical devices,[124] and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration[125] is concerned with automotive cybersecurity. After being criticized by the Government Accountability Office,[126] and following successful attacks on airports and claimed attacks on airplanes, the Federal Aviation Administration has devoted funding to securing systems on board the planes of private manufacturers, and the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System.[127] Concerns have also been raised about the future Next Generation Air Transportation System.[128]

Computer emergency readiness team

"Computer emergency response team" is a name given to expert groups that handle computer security incidents. In the US, two distinct organization exist, although they do work closely together.

- US-CERT: part of the National Cyber Security Division of the United States Department of Homeland Security.[129]

- CERT/CC: created by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and run by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI).

International actions

Many different teams and organisations exist, including:

- The Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) is the global association of CSIRTs.[130] The US-CERT, AT&T, Apple, Cisco, McAfee, Microsoft are all members of this international team.[131]

- The Council of Europe helps protect societies worldwide from the threat of cybercrime through the Convention on Cybercrime.[132]

- The purpose of the Messaging Anti-Abuse Working Group (MAAWG) is to bring the messaging industry together to work collaboratively and to successfully address the various forms of messaging abuse, such as spam, viruses, denial-of-service attacks and other messaging exploitations.[133] France Telecom, Facebook, AT&T, Apple, Cisco, Sprint are some of the members of the MAAWG.[134]

- ENISA : The European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA) is an agency of the European Union with the objective to improve network and information security in the European Union.

Europe

CSIRTs in Europe collaborate in the TERENA task force TF-CSIRT. TERENA's Trusted Introducer service provides an accreditation and certification scheme for CSIRTs in Europe. A full list of known CSIRTs in Europe is available from the Trusted Introducer website.

National teams

Here are the main computer emergency response teams around the world. Most countries have their own team to protect network security.

Canada

On October 3, 2010, Public Safety Canada unveiled Canada's Cyber Security Strategy, following a Speech from the Throne commitment to boost the security of Canadian cyberspace.[135][136] The aim of the strategy is to strengthen Canada's "cyber systems and critical infrastructure sectors, support economic growth and protect Canadians as they connect to each other and to the world."[136] Three main pillars define the strategy: securing government systems, partnering to secure vital cyber systems outside the federal government, and helping Canadians to be secure online.[136] The strategy involves multiple departments and agencies across the Government of Canada.[137] The Cyber Incident Management Framework for Canada outlines these responsibilities, and provides a plan for coordinated response between government and other partners in the event of a cyber incident.[138] The Action Plan 2010–2015 for Canada's Cyber Security Strategy outlines the ongoing implementation of the strategy.[139]

Public Safety Canada's Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre (CCIRC) is responsible for mitigating and responding to threats to Canada's critical infrastructure and cyber systems. The CCIRC provides support to mitigate cyber threats, technical support to respond and recover from targeted cyber attacks, and provides online tools for members of Canada's critical infrastructure sectors.[140] The CCIRC posts regular cyber security bulletins on the Public Safety Canada website.[141] The CCIRC also operates an online reporting tool where individuals and organizations can report a cyber incident.[142] Canada's Cyber Security Strategy is part of a larger, integrated approach to critical infrastructure protection, and functions as a counterpart document to the National Strategy and Action Plan for Critical Infrastructure.[137]

On September 27, 2010, Public Safety Canada partnered with STOP.THINK.CONNECT, a coalition of non-profit, private sector, and government organizations dedicated to informing the general public on how to protect themselves online.[143] On February 4, 2014, the Government of Canada launched the Cyber Security Cooperation Program.[144] The program is a $1.5 million five-year initiative aimed at improving Canada's cyber systems through grants and contributions to projects in support of this objective.[145] Public Safety Canada aims to begin an evaluation of Canada's Cyber Security Strategy in early 2015.[137] Public Safety Canada administers and routinely updates the GetCyberSafe portal for Canadian citizens, and carries out Cyber Security Awareness Month during October.[146]

China

China's network security and information technology leadership team was established February 27, 2014. The leadership team is tasked with national security and long-term development and co-ordination of major issues related to network security and information technology. Economic, political, cultural, social and military fields as related to network security and information technology strategy, planning and major macroeconomic policy are being researched. The promotion of national network security and information technology law are constantly under study for enhanced national security capabilities.

Germany

Berlin starts National Cyber Defense Initiative: On June 16, 2011, the German Minister for Home Affairs, officially opened the new German NCAZ (National Center for Cyber Defense) Nationales Cyber-Abwehrzentrum located in Bonn. The NCAZ closely cooperates with BSI (Federal Office for Information Security) Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik, BKA (Federal Police Organisation) Bundeskriminalamt (Deutschland), BND (Federal Intelligence Service) Bundesnachrichtendienst, MAD (Military Intelligence Service) Amt für den Militärischen Abschirmdienst and other national organisations in Germany taking care of national security aspects. According to the Minister the primary task of the new organisation founded on February 23, 2011, is to detect and prevent attacks against the national infrastructure and mentioned incidents like Stuxnet.

India

Some provisions for cybersecurity have been incorporated into rules framed under the Information Technology Act 2000.

The National Cyber Security Policy 2013 is a policy framework by Department of Electronics and Information Technology (DeitY) which aims to protect the public and private infrastructure from cyber attacks, and safeguard "information, such as personal information (of web users), financial and banking information and sovereign data".

The Indian Companies Act 2013 has also introduced cyber law and cyber security obligations on the part of Indian directors.

Pakistan

Cyber-crime has risen rapidly in Pakistan. There are about 34 million Internet users with 133.4 million mobile subscribers in Pakistan. According to Cyber Crime Unit (CCU), a branch of Federal Investigation Agency, only 62 cases were reported to the unit in 2007, 287 cases in 2008, ratio dropped in 2009 but in 2010, more than 312 cases were registered. However, there are many unreported incidents of cyber-crime.[147]

"Pakistan's Cyber Crime Bill 2007", the first pertinent law, focuses on electronic crimes, for example cyber-terrorism, criminal access, electronic system fraud, electronic forgery, and misuse of encryption.[147]

National Response Centre for Cyber Crime (NR3C) – FIA is a law enforcement agency dedicated to fight cybercrime. Inception of this Hi-Tech crime fighting unit transpired in 2007 to identify and curb the phenomenon of technological abuse in society.[148] However, certain private firms are also working in cohesion with the government to improve cyber security and curb cyberattacks.[149]

South Korea

Following cyberattacks in the first half of 2013, when government, news-media, television station, and bank websites were compromised, the national government committed to the training of 5,000 new cybersecurity experts by 2017. The South Korean government blamed its northern counterpart for these attacks, as well as incidents that occurred in 2009, 2011,[150] and 2012, but Pyongyang denies the accusations.[151]

Other countries

- CERT Brazil, member of FIRST (Forum for Incident Response and Security Teams)

- CARNet CERT, Croatia, member of FIRST

- AE CERT, United Arab Emirates

- SingCERT, Singapore

- CERT-LEXSI, France, Canada, Singapore

- INCIBE, Spain

- ID-CERT, Indonesia

Modern warfare

Cybersecurity is becoming increasingly important as more information and technology is being made available on cyberspace. There is growing concern among governments that cyberspace will become the next theatre of warfare. As Mark Clayton from the Christian Science Monitor described in an article titled "The New Cyber Arms Race":

In the future, wars will not just be fought by soldiers with guns or with planes that drop bombs. They will also be fought with the click of a mouse a half a world away that unleashes carefully weaponized computer programs that disrupt or destroy critical industries like utilities, transportation, communications, and energy. Such attacks could also disable military networks that control the movement of troops, the path of jet fighters, the command and control of warships.[152]

This has led to new terms such as cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism. More and more critical infrastructure is being controlled via computer programs that, while increasing efficiency, exposes new vulnerabilities. The test will be to see if governments and corporations that control critical systems such as energy, communications and other information will be able to prevent attacks before they occur. As Jay Cross, the chief scientist of the Internet Time Group, remarked, "Connectedness begets vulnerability."[152]

Job market

Cybersecurity is a fast-growing[153] field of IT concerned with reducing organizations' risk of hack or data breach. According to research from the Enterprise Strategy Group, 46% of organizations say that they have a "problematic shortage" of cybersecurity skills in 2016, up from 28% in 2015.[154] Commercial, government and non-governmental organizations all employ cybersecurity professionals. The fastest increases in demand for cybersecurity workers are in industries managing increasing volumes of consumer data such as finance, health care, and retail.[155] However, the use of the term "cybersecurity" is more prevalent in government job descriptions.[156]

Typical cybersecurity job titles and descriptions include:[157]

- Security analyst

- Analyzes and assesses vulnerabilities in the infrastructure (software, hardware, networks), investigates using available tools and countermeasures to remedy the detected vulnerabilities, and recommends solutions and best practices. Analyzes and assesses damage to the data/infrastructure as a result of security incidents, examines available recovery tools and processes, and recommends solutions. Tests for compliance with security policies and procedures. May assist in the creation, implementation, and/or management of security solutions.

- Security engineer

- Performs security monitoring, security and data/logs analysis, and forensic analysis, to detect security incidents, and mounts incident response. Investigates and utilizes new technologies and processes to enhance security capabilities and implement improvements. May also review code or perform other security engineering methodologies.

- Security architect

- Designs a security system or major components of a security system, and may head a security design team building a new security system.

- Security administrator

- Installs and manages organization-wide security systems. May also take on some of the tasks of a security analyst in smaller organizations.

- Chief Information Security Officer (CISO)

- A high-level management position responsible for the entire information security division/staff. The position may include hands-on technical work.

- Chief Security Officer (CSO)

- A high-level management position responsible for the entire security division/staff. A newer position now deemed needed as security risks grow.

- Security Consultant/Specialist/Intelligence

- Broad titles that encompass any one or all of the other roles/titles, tasked with protecting computers, networks, software, data, and/or information systems against viruses, worms, spyware, malware, intrusion detection, unauthorized access, denial-of-service attacks, and an ever increasing list of attacks by hackers acting as individuals or as part of organized crime or foreign governments.

Student programs are also available to people interested in beginning a career in cybersecurity.[158][159] Meanwhile, a flexible and effective option for information security professionals of all experience levels to keep studying is online security training, including webcasts.[160][161][162]

Terminology

The following terms used with regards to engineering secure systems are explained below.

- Access authorization restricts access to a computer to group of users through the use of authentication systems. These systems can protect either the whole computer – such as through an interactive login screen – or individual services, such as an FTP server. There are many methods for identifying and authenticating users, such as passwords, identification cards, and, more recently, smart cards and biometric systems.

- Anti-virus software consists of computer programs that attempt to identify, thwart and eliminate computer viruses and other malicious software (malware).

- Applications with known security flaws should not be run. Either leave it turned off until it can be patched or otherwise fixed, or delete it and replace it with some other application. Publicly known flaws are the main entry used by worms to automatically break into a system and then spread to other systems connected to it. The security website Secunia provides a search tool for unpatched known flaws in popular products.

- Authentication techniques can be used to ensure that communication end-points are who they say they are.

- Automated theorem proving and other verification tools can enable critical algorithms and code used in secure systems to be mathematically proven to meet their specifications.

- Backups are a way of securing information; they are another copy of all the important computer files kept in another location. These files are kept on hard disks, CD-Rs, CD-RWs, tapes and more recently on the cloud. Suggested locations for backups are a fireproof, waterproof, and heat proof safe, or in a separate, offsite location than that in which the original files are contained. Some individuals and companies also keep their backups in safe deposit boxes inside bank vaults. There is also a fourth option, which involves using one of the file hosting services that backs up files over the Internet for both business and individuals, known as the cloud.

- Backups are also important for reasons other than security. Natural disasters, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, or tornadoes, may strike the building where the computer is located. The building can be on fire, or an explosion may occur. There needs to be a recent backup at an alternate secure location, in case of such kind of disaster. Further, it is recommended that the alternate location be placed where the same disaster would not affect both locations. Examples of alternate disaster recovery sites being compromised by the same disaster that affected the primary site include having had a primary site in World Trade Center I and the recovery site in 7 World Trade Center, both of which were destroyed in the 9/11 attack, and having one's primary site and recovery site in the same coastal region, which leads to both being vulnerable to hurricane damage (for example, primary site in New Orleans and recovery site in Jefferson Parish, both of which were hit by Hurricane Katrina in 2005). The backup media should be moved between the geographic sites in a secure manner, in order to prevent them from being stolen.

- Capability and access control list techniques can be used to ensure privilege separation and mandatory access control. This section discusses their use.

- Chain of trust techniques can be used to attempt to ensure that all software loaded has been certified as authentic by the system's designers.

- Confidentiality is the nondisclosure of information except to another authorized person.[163]

- Cryptographic techniques can be used to defend data in transit between systems, reducing the probability that data exchanged between systems can be intercepted or modified.

- Cyberwarfare is an internet-based conflict that involves politically motivated attacks on information and information systems. Such attacks can, for example, disable official websites and networks, disrupt or disable essential services, steal or alter classified data, and cripple financial systems.

- Data integrity is the accuracy and consistency of stored data, indicated by an absence of any alteration in data between two updates of a data record.[164]

- Encryption is used to protect the message from the eyes of others. Cryptographically secure ciphers are designed to make any practical attempt of breaking infeasible. Symmetric-key ciphers are suitable for bulk encryption using shared keys, and public-key encryption using digital certificates can provide a practical solution for the problem of securely communicating when no key is shared in advance.

- Endpoint security software helps networks to prevent exfiltration (data theft) and virus infection at network entry points made vulnerable by the prevalence of potentially infected portable computing devices, such as laptops and mobile devices, and external storage devices, such as USB drives.[165]

- Firewalls are an important method for control and security on the Internet and other networks. A network firewall can be a communications processor, typically a router, or a dedicated server, along with firewall software. A firewall serves as a gatekeeper system that protects a company's intranets and other computer networks from intrusion by providing a filter and safe transfer point for access to and from the Internet and other networks. It screens all network traffic for proper passwords or other security codes and only allows authorized transmission in and out of the network. Firewalls can deter, but not completely prevent, unauthorized access (hacking) into computer networks; they can also provide some protection from online intrusion.

- Honey pots are computers that are either intentionally or unintentionally left vulnerable to attack by crackers. They can be used to catch crackers or fix vulnerabilities.

- Intrusion-detection systems can scan a network for people that are on the network but who should not be there or are doing things that they should not be doing, for example trying a lot of passwords to gain access to the network.

- A microkernel is the near-minimum amount of software that can provide the mechanisms to implement an operating system. It is used solely to provide very low-level, very precisely defined machine code upon which an operating system can be developed. A simple example is the early '90s GEMSOS (Gemini Computers), which provided extremely low-level machine code, such as "segment" management, atop which an operating system could be built. The theory (in the case of "segments") was that—rather than have the operating system itself worry about mandatory access separation by means of military-style labeling—it is safer if a low-level, independently scrutinized module can be charged solely with the management of individually labeled segments, be they memory "segments" or file system "segments" or executable text "segments." If software below the visibility of the operating system is (as in this case) charged with labeling, there is no theoretically viable means for a clever hacker to subvert the labeling scheme, since the operating system per se does not provide mechanisms for interfering with labeling: the operating system is, essentially, a client (an "application," arguably) atop the microkernel and, as such, subject to its restrictions.

- Pinging The ping application can be used by potential crackers to find if an IP address is reachable. If a cracker finds a computer, they can try a port scan to detect and attack services on that computer.

- Social engineering awareness keeps employees aware of the dangers of social engineering and/or having a policy in place to prevent social engineering can reduce successful breaches of the network and servers.

Scholars

- Ross J. Anderson

- Annie Anton

- Adam Back

- Daniel J. Bernstein

- Matt Blaze

- Stefan Brands

- L. Jean Camp

- Lance Cottrell

- Lorrie Cranor

- Dorothy E. Denning

- Peter J. Denning

- Cynthia Dwork

- Deborah Estrin

- Joan Feigenbaum

- Ian Goldberg

- Shafi Goldwasser

- Lawrence A. Gordon

- Peter Gutmann

- Paul Kocher

- Monica S. Lam

- Butler Lampson

- Brian LaMacchia

- Carl Landwehr

- Kevin Mitnick

- Peter G. Neumann

- Susan Nycum

- Roger R. Schell

- Bruce Schneier

- Dawn Song

- Gene Spafford

- Joseph Steinberg

- Salvatore J. Stolfo

- Willis Ware

- Moti Yung

See also

- Attack tree

- CAPTCHA

- CERT

- CertiVox

- Cloud computing security

- Common Criteria

- Comparison of antivirus software

- Computer security model

- Content Disarm & Reconstruction

- Content security

- Countermeasure (computer)

- Cyber hygiene

- Cyber Insurance

- Cyber security standards

- Dancing pigs

- Data loss prevention software

- Data security

- Differentiated security

- Disk encryption

- Exploit (computer security)

- Fault tolerance

- Human–computer interaction (security)

- Identity management

- Identity theft

- Identity-based security

- Information security awareness

- Internet privacy

- IT risk

- Kill chain

- List of Computer Security Certifications

- Mobile security

- Network security

- Network Security Toolkit

- Next-Generation Firewall

- Open security

- OWASP

- Penetration test

- Physical information security

- Presumed security

- Privacy software

- Proactive cyber defence

- Risk cybernetics

- Sandbox (computer security)

- Separation of protection and security

- Software Defined Perimeter

Further reading

- Wu, Chwan-Hwa (John); Irwin, J. David (2013). Introduction to Computer Networks and Cybersecurity. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1466572133.

- Lee, Newton (2015). Counterterrorism and Cybersecurity: Total Information Awareness (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-17243-9.

- Singer, P. W.; Friedman, Allan (2014). Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199918119.

- Kim, Peter (2014). The Hacker Playbook: Practical Guide To Penetration Testing. Seattle: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1494932633.

References

- ↑ Gasser, Morrie (1988). Building a Secure Computer System (PDF). Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 3. ISBN 0-442-23022-2. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ "Definition of computer security". Encyclopedia. Ziff Davis, PCMag. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Rouse, Margaret. "Social engineering definition". TechTarget. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ "Reliance spells end of road for ICT amateurs", May 07, 2013, The Australian

- ↑ "Computer Security and Mobile Security Challenges" (pdf). researchgate.net. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ↑ "Distributed Denial of Service Attack". csa.gov.sg. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Wireless mouse leave billions at risk of computer hack: cyber security firm

- ↑

- ↑ Gallagher, Sean (May 14, 2014). "Photos of an NSA "upgrade" factory show Cisco router getting implant". Ars Technica. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Identifying Phishing Attempts". Case.

- ↑ Arcos Sergio. "Social Engineering" (PDF).

- ↑ Scannell, Kara (24 Feb 2016). "CEO email scam costs companies $2bn". Financial Times (25 Feb 2016). Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bucks leak tax info of players, employees as result of email scam". Associated Press. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ J. C. Willemssen, "FAA Computer Security". GAO/T-AIMD-00-330. Presented at Committee on Science, House of Representatives, 2000.

- ↑ Financial Weapons of War, Minnesota Law Review (2016), available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2765010

- ↑ Pagliery, Jose. "Hackers attacked the U.S. energy grid 79 times this year". CNN Money. Cable News Network. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ "Vulnerabilities in Smart Meters and the C12.12 Protocol". SecureState. 2012-02-16. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ P. G. Neumann, "Computer Security in Aviation," presented at International Conference on Aviation Safety and Security in the 21st Century, White House Commission on Safety and Security, 1997.

- ↑ J. Zellan, Aviation Security. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science, 2003, pp. 65–70.

- ↑ "Air Traffic Control Systems Vulnerabilities Could Make for Unfriendly Skies [Black Hat] - SecurityWeek.Com".

- ↑ "Hacker Says He Can Break Into Airplane Systems Using In-Flight Wi-Fi". NPR.org. 4 August 2014.

- ↑ Jim Finkle (4 August 2014). "Hacker says to show passenger jets at risk of cyber attack". Reuters.

- ↑ "Pan-European Network Services (PENS) - Eurocontrol.int".

- ↑ "Centralised Services: NewPENS moves forward - Eurocontrol.int".

- ↑ "NextGen Program About Data Comm - FAA.gov".

- 1 2 "Is Your Watch Or Thermostat A Spy? Cybersecurity Firms Are On It". NPR.org. 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Melvin Backman (18 September 2014). "Home Depot: 56 million cards exposed in breach". CNNMoney.

- ↑ "Staples: Breach may have affected 1.16 million customers' cards". Fortune.com. December 19, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-21.

- ↑ "Target security breach affects up to 40M cards". Associated Press via Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Jim Finkle (23 April 2014). "Exclusive: FBI warns healthcare sector vulnerable to cyber attacks". Reuters. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Bright, Peter (February 15, 2011). "Anonymous speaks: the inside story of the HBGary hack". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ Anderson, Nate (February 9, 2011). "How one man tracked down Anonymous—and paid a heavy price". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ Palilery, Jose (December 24, 2014). "What caused Sony hack: What we know now". CNN Money. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ↑ James Cook (December 16, 2014). "Sony Hackers Have Over 100 Terabytes Of Documents. Only Released 200 Gigabytes So Far". Business Insider. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- 1 2 Timothy B. Lee (18 January 2015). "The next frontier of hacking: your car". Vox.

- ↑ Stephen Checkoway; Damon McCoy; Brian Kantor; Danny Anderson; Hovav Shacham; Stefan Savage; Karl Koscher; Alexei Czeskis; Franziska Roesner; Tadayoshi Kohno (2011). Comprehensive Experimental Analyses of Automotive Attack Surfaces (PDF). SEC'11 Proceedings of the 20th USENIX conference on Security. Berkeley, CA, US: USENIX Association. pp. 6–6.

- ↑ Tracking & Hacking: Security & Privacy Gaps Put American Drivers at Risk (PDF) (Report). 2015-02-06. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Internet strikes back: Anonymous' Operation Megaupload explained". RT. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Gary McKinnon profile: Autistic 'hacker' who started writing computer programs at 14". The Daily Telegraph. London. 23 January 2009.

- ↑ "Gary McKinnon extradition ruling due by 16 October". BBC News. September 6, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ↑ Law Lords Department (30 July 2008). "House of Lords – Mckinnon V Government of The United States of America and Another". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

15. … alleged to total over $700,000

- ↑ "NSA Accessed Mexican President's Email", October 20, 2013, Jens Glüsing, Laura Poitras, Marcel Rosenbach and Holger Stark, spiegel.de

- ↑ Sanders, Sam (4 June 2015). "Massive Data Breach Puts 4 Million Federal Employees' Records At Risk". NPR. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Liptak, Kevin (4 June 2015). "U.S. government hacked; feds think China is the culprit". CNN. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Sean Gallagher. "Encryption "would not have helped" at OPM, says DHS official".

- ↑ "Schools Learn Lessons From Security Breaches". Education Week. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Internet of Things Global Standards Initiative". ITU. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ Singh, Jatinder; Pasquier, Thomas; Bacon, Jean; Ko, Hajoon; Eyers, David (2015). "Twenty Cloud Security Considerations for Supporting the Internet of Things". IEEE Internet of Things Journal: 1–1. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2015.2460333.

- ↑ Chris Clearfield. "Why The FTC Can't Regulate The Internet Of Things". Forbes. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ "Internet of Things: Science Fiction or Business Fact?" (PDF). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Ovidiu Vermesan; Peter Friess. "Internet of Things: Converging Technologies for Smart Environments and Integrated Ecosystems" (PDF). River Publishers. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Christopher Clearfield "Rethinking Security for the Internet of Things" Harvard Business Review Blog, 26 June 2013/

- ↑ "Hotel room burglars exploit critical flaw in electronic door locks". Ars Technica. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Hospital Medical Devices Used As Weapons In Cyberattacks". Dark Reading. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Jeremy Kirk (17 October 2012). "Pacemaker hack can deliver deadly 830-volt jolt". Computerworld. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "How Your Pacemaker Will Get Hacked". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Cashell, B., Jackson, W. D., Jickling, M., & Webel, B. (2004). The Economic Impact of Cyber-Attacks. Congressional Research Service, Government and Finance Division. Washington DC: The Library of Congress.

- ↑ Gordon, Lawrence; Loeb, Martin (November 2002). "The Economics of Information Security Investment". ACM Transactions on Information and System Security. 5 (4): 438–457. doi:10.1145/581271.581274.

- ↑ RFC 2828 Internet Security Glossary

- ↑ CNSS Instruction No. 4009 dated 26 April 2010

- ↑ InfosecToday Glossary

- ↑ Definitions: IT Security Architecture. SecurityArchitecture.org, Jan, 2006

- ↑ Jannsen, Cory. "Security Architecture". Techopedia. Janalta Interactive Inc. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Cybersecurity at petabyte scale".

- ↑ Woodie, Alex (9 May 2016). "Why ONI May Be Our Best Hope for Cyber Security Now". Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Firms lose more to electronic than physical theft". Reuters.

- ↑ Foreman, P: Vulnerability Management, page 1. Taylor & Francis Group, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4398-0150-5

- ↑ Anna-Maija Juuso and Ari Takanen Unknown Vulnerability Management, Codenomicon whitepaper, October 2010 .

- ↑ Alan Calder and Geraint Williams. PCI DSS: A Pocket Guide, 3rd Edition. ISBN 978-1-84928-554-4.

network vulnerability scans at least quarterly and after any significant change in the network

- ↑ Harrison, J. (2003). "Formal verification at Intel": 45–54. doi:10.1109/LICS.2003.1210044.

- ↑ Umrigar, Zerksis D.; Pitchumani, Vijay (1983). "Formal verification of a real-time hardware design". Proceeding DAC '83 Proceedings of the 20th Design Automation Conference. IEEE Press. pp. 221–7. ISBN 0-8186-0026-8.

- ↑ "Abstract Formal Specification of the seL4/ARMv6 API" (PDF). Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ↑ Christoph Baumann, Bernhard Beckert, Holger Blasum, and Thorsten Bormer Ingredients of Operating System Correctness? Lessons Learned in the Formal Verification of PikeOS

- ↑ "Getting it Right" by Jack Ganssle

- ↑ Arachchilage, Nalin; Love, Steve; Scott, Michael (June 1, 2012). "Designing a Mobile Game to Teach Conceptual Knowledge of Avoiding 'Phishing Attacks'". International Journal for e-Learning Security. Infonomics Society. 2 (1): 127–132. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ Scott, Michael; Ghinea, Gheorghita; Arachchilage, Nalin (7 July 2014). Assessing the Role of Conceptual Knowledge in an Anti-Phishing Educational Game (pdf). Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies. IEEE. p. 218. doi:10.1109/ICALT.2014.70. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ "The Hacker in Your Hardware: The Next Security Threat". Scientific American.

- ↑ Waksman, Adam; Sethumadhavan, Simha (2010), "Tamper Evident Microprocessors" (PDF), Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, California

- ↑ "Sentinel HASP HL". E-Spin. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ↑ "Token-based authentication". SafeNet.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ↑ "Lock and protect your Windows PC". TheWindowsClub.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ↑ James Greene (2012). "Intel Trusted Execution Technology: White Paper" (PDF). Intel Corporation. Retrieved 2013-12-18.

- ↑ "SafeNet ProtectDrive 8.4". SCMagazine.com. 2008-10-04. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ↑ "Secure Hard Drives: Lock Down Your Data". PCMag.com. 2009-05-11.

- ↑ "Top 10 vulnerabilities inside the network". Network World. 2010-11-08. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ↑ "Forget IDs, use your phone as credentials". Fox Business Network. 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ↑ Lipner, Steve (2015). "The Birth and Death of the Orange Book". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 37 (2): 19–31. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2015.27.

- ↑ Kelly Jackson Higgins (2008-11-18). "Secure OS Gets Highest NSA Rating, Goes Commercial". Dark Reading. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ↑ "Board or bored? Lockheed Martin gets into the COTS hardware biz". VITA Technologies Magazine. December 10, 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ Sanghavi, Alok (21 May 2010). "What is formal verification?". EE Times_Asia.

- 1 2 Jonathan Zittrain, 'The Future of The Internet', Penguin Books, 2008

- ↑ Information Security. United States Department of Defense, 1986

- ↑ "THE TJX COMPANIES, INC. VICTIMIZED BY COMPUTER SYSTEMS INTRUSION; PROVIDES INFORMATION TO HELP PROTECT CUSTOMERS" (Press release). The TJX Companies, Inc. 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ Largest Customer Info Breach Grows. MyFox Twin Cities, 29 March 2007.

- ↑ "The Stuxnet Attack On Iran's Nuclear Plant Was 'Far More Dangerous' Than Previously Thought". Business Insider. 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Reals, Tucker (24 September 2010). "Stuxnet Worm a U.S. Cyber-Attack on Iran Nukes?". CBS News.

- ↑ Kim Zetter (17 February 2011). "Cyberwar Issues Likely to Be Addressed Only After a Catastrophe". Wired. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ↑ Chris Carroll (18 October 2011). "Cone of silence surrounds U.S. cyberwarfare". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ John Bumgarner (27 April 2010). "Computers as Weapons of War" (PDF). IO Journal. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ Newman, Lily Hay (9 October 2013). "Can You Trust NIST?". IEEE Spectrum.

- ↑ "New Snowden Leak: NSA Tapped Google, Yahoo Data Centers", Oct 31, 2013, Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai, mashable.com

- ↑ Seipel, Hubert. "Transcript: ARD interview with Edward Snowden". La Foundation Courage. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ↑ Michael Riley; Ben Elgin; Dune Lawrence; Carol Matlack. "Target Missed Warnings in Epic Hack of Credit Card Data - Businessweek". Businessweek.com.

- ↑ "Home Depot says 53 million emails stolen". CNET. CBS Interactive. 6 November 2014.

- ↑ Mansfield-Devine, Steve (2015-09-01). "The Ashley Madison affair". Network Security. 2015 (9): 8–16. doi:10.1016/S1353-4858(15)30080-5.

- 1 2 "Mikko Hypponen: Fighting viruses, defending the net". TED.

- ↑ "Mikko Hypponen – Behind Enemy Lines". Hack In The Box Security Conference.