Kama Sutra

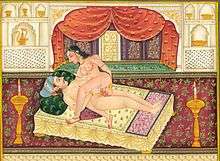

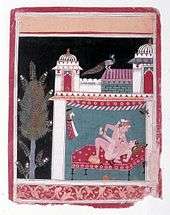

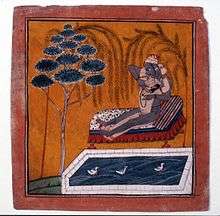

The Kama Sutra (Sanskrit: कामसूत्र ![]() pronunciation , Kāmasūtra) is an ancient Indian Hindu[1][2] text written by Vātsyāyana. It is widely considered to be the standard work on human sexual behaviour in Sanskrit literature.

pronunciation , Kāmasūtra) is an ancient Indian Hindu[1][2] text written by Vātsyāyana. It is widely considered to be the standard work on human sexual behaviour in Sanskrit literature.

A portion of the work consists of practical advice on sexual intercourse.[3] It is largely in prose, with many inserted anustubh poetry verses. "Kāma" which is one of the four goals of Hindu life, means desire including sexual desire the latter being the subject of the textbook, and "sūtra" literally means a thread or line that holds things together, and more metaphorically refers to an aphorism (or line, rule, formula), or a collection of such aphorisms in the form of a manual.

Contrary to western popular perception, the Kama Sutra is not exclusively a sex manual; it presents itself as a guide to a virtuous and gracious living that discusses the nature of love, family life and other aspects pertaining to pleasure oriented faculties of human life.[4][5] Kama Sutra, in parts of the world, is presumed or depicted as a synonym for creative sexual positions; in reality, only 20% of Kama Sutra is about sexual positions. The majority of the book, notes Jacob Levy,[6] is about the philosophy and theory of love, what triggers desire, what sustains it, how and when it is good or bad.[7]

The Kama Sutra is the oldest and most notable of a group of texts known generically as Kama Shastra (Sanskrit: Kāma Śāstra).[8]

Historians attribute Kamasutra to be composed between 400 BCE and 200 CE.[9] John Keay says that the Kama Sutra is a compendium that was collected into its present form in the 2nd century CE.[10]

Content

In the preface of Kama Sutra, Vatsyayana cites the work of previous authors based on which he compiled his own Kama Sutra. He states that the seven parts of his work were an abridgment of longer works by Dattaka (first part), Suvarnanabha (second part), Ghotakamukha (third part), Gonardiya (fourth part), Gonikaputra (fifth part), Charayana (sixth part), and Kuchumara (seventh part). Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra has 1250 verses, distributed in 36 chapters, which are further organised into seven parts.[11] According to both the Burton and Doniger[12] translations, the contents of the book are structured into seven parts like the following:

- 1. General remarks

- five chapters on contents of the book, three aims and priorities of life, the acquisition of knowledge, conduct of the well-bred townsman, reflections on intermediaries who assist the lover in his enterprises.

- 2. Amorous advances/sexual union

- ten chapters on stimulation of desire, types of embraces, caressing and kisses, marking with nails, biting and marking with teeth, on copulation (positions), slapping by hand and corresponding moaning, virile behaviour in women, superior coition and oral sex, preludes and conclusions to the game of love. It describes 64 types of sexual acts.

- 3. Acquiring a wife

- five chapters on forms of marriage, relaxing the girl, obtaining the girl, managing alone, union by marriage.

- 4. Duties and privileges of the wife

- two chapters on conduct of the only wife and conduct of the chief wife and other wives.

- 5. Other men's wives

- six chapters on behaviour of woman and man, how to get acquainted, examination of sentiments, the task of go-between, the king's pleasures, behaviour in the women's quarters.

- 6. About courtesans

- six chapters on advice of the assistants on the choice of lovers, looking for a steady lover, ways of making money, renewing friendship with a former lover, occasional profits, profits and losses.

- 7. Occult practices

- two chapters on improving physical attractions, arousing a weakened sexual power.

Pleasure and spirituality

Some Indian philosophies follow the "four main goals of life",[13][14] known as the purusharthas:[15]

Dharma, Artha and Kama are aims of everyday life, while Moksha is release from the cycle of death and rebirth. The Kama Sutra (Burton translation) says:

Dharma is better than Artha, and Artha is better than Kama. But Artha should always be first practised by the king for the livelihood of men is to be obtained from it only. Again, Kama being the occupation of public women, they should prefer it to the other two, and these are exceptions to the general rule.

- —Kama Sutra 1.2.14[16]

Of the first three, virtue is the highest goal, a secure life the second and pleasure the least important. When motives conflict, the higher ideal is to be followed. Thus, in making money virtue must not be compromised, but earning a living should take precedence over pleasure, but there are exceptions.

In childhood, Vātsyāyana says, a person should learn how to make a living; youth is the time for pleasure, and as years pass one should concentrate on living virtuously and hope to escape the cycle of rebirth.[17] The Kama Sutra acknowledges that the senses can be dangerous: 'Just as a horse in full gallop, blinded by the energy of his own speed, pays no attention to any post or hole or ditch on the path, so two lovers, blinded by passion, in the friction of sexual battle, are caught up in their fierce energy and pay no attention to danger' (2.7.33).

Also the Buddha preached a Kama Sutra, which is located in the Atthakavagga (sutra number 1). This Kama Sutra, however, is of a very different nature as it warns against the dangers that come with the search for pleasures of the senses.

Many in the Western world wrongly consider the Kama Sutra to be a manual for tantric sex. While sexual practices do exist within the very wide tradition of Hindu Tantra, the Kama Sutra is not a Tantric text, and does not touch upon any of the sexual rites associated with some forms of Tantric practice.

Translations

The most widely known English translation of the Kama Sutra was privately printed in 1883. It is usually attributed to renowned orientalist and author Sir Richard Francis Burton, but the chief work was done by the Indian archaeologist Bhagwan Lal Indraji, under the guidance of Burton's friend, the Indian civil servant Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, and with the assistance of a student, Shivaram Parshuram Bhide.[18] Burton acted as publisher, while also furnishing the edition with footnotes whose tone ranges from the jocular to the scholarly. Burton says the following in its introduction:

It may be interesting to some persons to learn how it came about that Vatsyayana was first brought to light and translated into the English language. It happened thus. While translating with the pundits the 'Anunga Runga, or the stage of love', reference was frequently found to be made to one Vatsya. The sage Vatsya was of this opinion, or of that opinion. The sage Vatsya said this, and so on. Naturally questions were asked who the sage was, and the pundits replied that Vatsya was the author of the standard work on love in Sanscrit[sic] literature, that no Sanscrit library was complete without his work, and that it was most difficult now to obtain in its entire state. The copy of the manuscript obtained in Bombay was defective, and so the pundits wrote to Benares, Calcutta and Jaipur for copies of the manuscript from Sanscrit libraries in those places. Copies having been obtained, they were then compared with each other, and with the aid of a Commentary called 'Jayamanglia' a revised copy of the entire manuscript was prepared, and from this copy the English translation was made. The following is the certificate of the chief pundit:

"The accompanying manuscript is corrected by me after comparing four different copies of the work. I had the assistance of a Commentary called 'Jayamangla' for correcting the portion in the first five parts, but found great difficulty in correcting the remaining portion, because, with the exception of one copy thereof which was tolerably correct, all the other copies I had were far too incorrect. However, I took that portion as correct in which the majority of the copies agreed with each other."

In the introduction to her own translation, Wendy Doniger, professor of the history of religions at the University of Chicago, writes that Burton "managed to get a rough approximation of the text published in English in 1883, nasty bits and all". The philologist and Sanskritist Professor Chlodwig Werba, of the Institute of Indology at the University of Vienna, regards the 1883 translation as being second only in accuracy to the academic German-Latin text published by Richard Schmidt in 1897.[19]

A noteworthy translation by Indra Sinha was published in 1980. In the early 1990s its chapter on sexual positions began circulating on the internet as an independent text and today is often assumed to be the whole of the Kama Sutra.[20]

Alain Daniélou contributed a noteworthy translation called The Complete Kama Sutra in 1994.[21] This translation, originally into French, and thence into English, featured the original text attributed to Vatsyayana, along with a medieval and a modern commentary. Unlike the 1883 version, Daniélou's new translation preserves the numbered verse divisions of the original, and does not incorporate notes in the text. He includes English translations of two important commentaries:

- The Jayamangala commentary, written in Sanskrit by Yashodhara during the Middle Ages, as page footnotes.

- A modern commentary in Hindi by Devadatta Shastri, as endnotes.

Daniélou[22] translated all Sanskrit words into English (but uses the word "brahmin"). He leaves references to the sexual organs as in the original: persistent usage of the words "lingam" and "yoni" to refer to them in older translations of the Kama Sutra is not the usage in the original Sanskrit; he argues that "to a modern Hindu 'lingam' and 'yoni' mean specifically the sexual organs of the god Shiva and his wife, and using those words to refer to humans' sexual organs would seem irreligious." The view that lingam means only "sexual organs" is disputed by academics such as S. N. Balagangadhara.[23]

An English translation by Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar, an Indian psychoanalyst and senior fellow at Center for Study of World Religions at Harvard University, was published by Oxford University Press in 2002. Doniger contributed the Sanskrit expertise while Kakar provided a psychoanalytic interpretation of the text.[24]

See also

- History of sex in India

- Kamashastra

- Khajuraho Group of Monuments

- Lazzat Un Nisa

- List of Indian inventions and discoveries

- Song of Songs

- The Jewel in The Lotus

- The Perfumed Garden

- Vatsyayana cipher

- Mlecchita vikalpa

Popular culture

- Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love

- Tales of the Kama Sutra: The Perfumed Garden

- Tales of the Kama Sutra 2: Monsoon

- Kamasutra 3D

- Kamasutra Nights

References

- ↑ Doniger, Wendy (2003). Kamasutra – Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. p. i. ISBN 978-0-19-283982-4.

The Kamasutra is the oldest extant Hindu textbook of erotic love. It was composed in Sanskrit, the literary language of ancient India, probably in North India and probably sometime in the third century

- ↑ Coltrane, Scott (1998). Gender and families. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8039-9036-4.

- ↑ Common misconceptions about Kama Sutra. "The Kama Sutra is neither exclusively a sex manual nor, as also commonly used art, a sacred or religious work. It is certainly not a tantric text. In opening with a discussion of the three aims of ancient Hindu life – dharma, artha and kama – Vatsyayana's purpose is to set kama, or enjoyment of the senses, in context. Thus dharma or virtuous living is the highest aim, artha, the amassing of wealth is next, and kama is the least of three." —Indra Sinha.

- ↑ Carroll, Janell (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3.

- ↑ Devi, Chandi (2008). From Om to Orgasm: The Tantra Primer for Living in Bliss. AuthorHouse. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-4343-4960-6.

- ↑ Jacob Levy (2010), Kama sense marketing, iUniverse, ISBN 978-1440195563, see Introduction

- ↑ Alain Daniélou, The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text, ISBN 978-0892815258.

- ↑ For Kama Sutra as the most notable of the kāma śhāstra literature see: Flood (1996), p. 65.

- ↑ Sengupta, J. (2006). Refractions of Desire, Feminist Perspectives in the Novels of Toni Morrison, Michèle Roberts, and Anita Desai. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 21. ISBN 9788126906291. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ↑ John Keay (2010). India: A History: from the Earliest Civilisations to the Boom of the Twenty-first Century. Grove Press. pp. 81–103.

- ↑ book, see index pages by Wendy Doniger, also translation by Burton

- ↑ Date checked: 29 March 2007 Burton and Doniger

- ↑ For the Dharma Śāstras as discussing the "four main goals of life" (dharma, artha, kāma, and moksha) see: Hopkins, p. 78.

- ↑ For dharma, artha, and kama as "brahmanic householder values" see: Flood (1996), p. 17.

- ↑ For definition of the term पुरुष-अर्थ (puruṣa-artha) as "any of the four principal objects of human life, i.e. धर्म (dharma), अर्थ (artha), काम (kāma), and मोक्ष (mokṣa)" see: Apte, p. 626, middle column, compound #1.

- ↑ Quotation from the translation by Richard Burton taken from . Text accessed 3 April 2007.

- ↑ Book I, Chapter ii, Lines 2-4 Vatsyayana Kamasutram Electronic Sanskrit edition: Titus Texts, University of Frankfurt bālye vidyāgrahaṇādīn arthān, kāmaṃ ca yauvane, sthāvire dharmaṃ mokṣaṃ ca

- ↑ McConnachie (2007), pp. 123–125.

- ↑ McConnachie (2007), p. 233.

- ↑ Sinha, p. 33.

- ↑ The Complete Kama Sutra by Alain Daniélou.

- ↑ Stated in the translation's preface

- ↑ Balagangadhara, S. N. (2007). Antonio De Nicholas, Krishnan Ramaswamy, Aditi Banerjee, eds. Invading the Sacred. Rupa & Co. pp. 431–433. ISBN 978-81-291-1182-1.

- ↑ McConnachie (2007), p. 232.

Bibliography

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (fourth revised & enlarged ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4.

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9.

- Daniélou, Alain (1993). The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text. Inner Traditions. ISBN 0-89281-525-6.

- Doniger, Wendy; Sudhir Kakar (2002). Kamasutra. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283982-9.

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5.

- Hopkins, Thomas J. (1971). The Hindu Religious Tradition. Cambridge: Dickenson Publishing Company, Inc.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- McConnachie, James (2007). The Book of Love: In Search of the Kamasutra. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-373-2.

- Sinha, Indra (1999). The Cybergypsies. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-600-34158-5.

External links

Original and translations

- Sir Richard Burton's English translation on Indohistory.com

-

The Kama Sutra public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Kama Sutra public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Kama Sutra in the original Sanskrit provided by the TITUS project

- Kama Sutra at Project Gutenberg