Pinya Kingdom

| Kingdom of Pinya | ||||||||||||

| ပင်းယခေတ် | ||||||||||||

| Kingdom | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

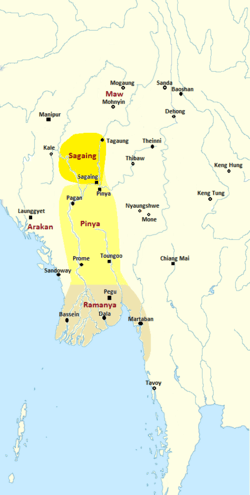

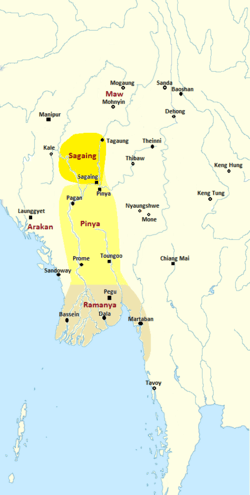

Pinya Kingdom c. 1350 | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Pinya | |||||||||||

| Languages | Burmese (official) Mon, Shan | |||||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism, Ari Buddhism, Animism | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||

| • | 1313–25 | Thihathu | ||||||||||

| • | 1325–40 | Uzana I | ||||||||||

| • | 1344–50 | Kyawswa I | ||||||||||

| • | 1359–64 | Narathu | ||||||||||

| Regent | ||||||||||||

| • | 1340–44 | Sithu | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Hluttaw | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Warring states | |||||||||||

| • | Myinsaing Regency founded | 17 December 1297 | ||||||||||

| • | Pinya Kingdom founded | 7 February 1313 | ||||||||||

| • | Sagaing secession | 1315–17 (de facto) 1325 (de jure) | ||||||||||

| • | Uzana I–Kyawswa I rivalry | 1325–44 | ||||||||||

| • | Toungoo secession | 1358–59 | ||||||||||

| • | Maw raids | 1358–64 | ||||||||||

| • | Ava Kingdom founded | 26 February 1365 | ||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||

| • | 1313 | 140,000 km² (54,054 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| • | 1325 | 100,000 km² (38,610 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| • | 1360 | 80,000 km² (30,888 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||

| History of Myanmar |

|---|

_peacock.svg.png) |

|

|

|

|

The Pinya Kingdom (Burmese: ပင်းယခေတ်, pronounced: [pɪ́ɴja̰ kʰɪʔ]) was the kingdom that ruled Central Myanmar (Burma) from 1313 to 1365. It was the successor state of Myinsaing, the polity that controlled much of Upper Burma between 1297 and 1313. Founded as the de jure successor state of the Pagan Empire by Thihathu, Pinya faced internal divisions from the start. The northern province of Sagaing led by Thihathu's eldest son Saw Yun successfully fought for autonomy in 1315−17, and formally seceded in 1325 after Thihathu's death.

The rump Pinya Kingdom was left embroiled in an intense rivalry between Thihathu's other sons Uzana I and Kyawswa I until 1344. Pinya had little control over its vassals; its southernmost vassals Toungoo (Toungoo) and Prome (Pyay) were practically independent. Central authority briefly returned during Kyawswa I's reign (1344−50) but broke down right after his death. In the 1350s, Kyawswa II repaired Pinya's long-strained relationship with Sagaing, in order to face off against the northern Shan state of Maw. The two Maw raids in 1358–59 and 1362–63 thoroughly devastated Pinya's countryside during which Toungoo successfully broke away. Narathu switched sides and aided the Maw attack on Sagaing in 1363–64. But after the Maw troops sacked both Sagaing and Pinya in succession in 1364, Thihathu's great grandson Thado Minbya of Sagaing seized both devastated capitals in 1364, and founded the Ava Kingdom in 1365.

Pinya was a microcosm of the small kingdoms period (1287–1555) of Burmese history. Weakened by internal divisions, Pinya despite controlling two of the three main granaries never reached its potential. Although its successor Ava would prove more successful in reassembling major parts of the erstwhile empire, it too would be hampered by fierce regional rivalries, and Myanmar would remain divided into the mid-16th century.

History

Early period

Myinsaing regency

Pinya was the successor state of Myinsaing, the polity that succeeded the Pagan Empire in Upper Burma.[note 1] After the Mongol invasions (1277–87), the Mongols seized northern Burma to Tagaung, and the rest of the empire broke up into several petty states. Pagan was left holding only a small region around the capital. In 1297, the three former Pagan commanders— Athinkhaya, Yazathingyan and Thihathu—overthrew King Kyawswa of Pagan (r. 1289–97), who had become a Mongol vassal nine months earlier.[1][2] The brothers placed a puppet king, and ruled from their base in Kyaukse. The Mongols invaded once again in 1300–01 but could not break through. They withdrew altogether from northern Burma in 1303.[3]

The brothers went on to reassemble the core regions of the fallen empire. In the north, they regained up to Tagaung but no further. Various Shan states, nominal Mongol vassals, now dominated the entire northwestern-to-southeastern arc surrounding the Irrawaddy valley. In the south, the brothers established suzerainty down to Prome (Pyay), and Toungoo (Taungoo).[note 2] They did not try to regain Ramanya farther south,[note 3] or Arakan in the west.

The regency of the triumvirate was short-lived. Thihathu, the youngest and most ambitious brother, was never satisfied with a mere regent status, and declared himself king in 1309.[4] The proclamation ended the charade of Saw Hnit's nominal status as king.[5] The old power structure at Pagan led by the dowager queen Pwa Saw was not happy but there was little she or Saw Hnit could do. It is not clear what the two elder brothers made of their brother's announcement.[note 4] At any rate, the elder brothers died in 1310 and 1312/13,[note 5] and Thihathu became the undisputed ruler.

Early Pinya

To commemorate his reign, Thihathu founded a new capital at Pinya, also in the Kyaukse valley but closer to the Irrawaddy. He decided to keep his capital in the premier granary instead of returning to Pagan (Bagan) because Pinya was closer to the Mu valley granary in the north.[6] On 7 February 1313, Thihathu, of non-royal birth, was crowned king as the rightful heir of the Pagan kings by Queen Pwa Saw herself.[7]

For the first time since the 1280s, the entire Irrawaddy valley between Prome in the south and Tagaung in the north was under a single ruler. However, Pinya’s authority over the frontier regions such as Prome and Toungoo was nominal. The Myinsaing-Pinya rulers had inherited the longstanding problem that had existed since the late Pagan period: between one and two-thirds of Upper Burma's cultivated land had been donated to religion, and the crown had lost resources needed to retain the loyalty of courtiers and military servicemen.[8] Furthermore, "markedly drier weather during the late 13th and much of the 14th centuries" in Upper Burma forced large migrations from the established granaries (Kyaukse, Minbu, and Mu valley)[9] "to better watered districts farther south".[10]

To compound the problem, Pinya was hit with a dynastic feud from the start. So eager was Thihathu to be seen as a legitimate king of Pagan, he made his adopted stepson Uzana, biological son of King Kyawswa of Pagan and Queen Mi Saw U, his heir-apparent. He also appointed Kyawswa I, his biological son by Mi Saw U, governor of Pinle, the second most coveted position.[11] On the other hand, the king did not appoint Saw Yun, his eldest biological son by a commoner queen, Yadanabon, or Tarabya his stepson by Yadanabon, to any meaningful positions. He appointed Saw Yun governor of Sagaing in 1314 only after the eldest son's repeated protestations.[12][13] Saw Yun remained deeply unhappy for he still did not command an army as did Uzana and Kyawswa.[12]

Sagaing secession

The simmering resentment led to Saw Yun's insurrection. The young prince upgraded Sagaing's timber walls to brick without his father's permission in 1315–16.[14] Thihathu seemed conflicted about punishing his teenage son. The king, who had never liked to share power—even with his own brothers—never sent a full force to reclaim Sagaing. He did order two small expeditions, the first led by Crown Prince Uzana and the second led by Prince Kyawswa. But by the end of 1316–17 dry season, both expeditions had failed to dislodge Saw Yun.[15]

Sagaing got a breather in 1317 when Toungoo and Taungdwin revolted. Thihathu bought peace with Taungdwin but Toungoo required an expedition. In the end, Pinya agreed to a deal that allowed the rebel leader Thawun Nge to remain in office in exchange for his nominal submission to Pinya.[16][17] The deal with Toungoo proved to be the model for Sagaing as well. The king allowed Saw Yun to remain in office at Sagaing in exchange for his son’s nominal submission. He was resigned to the fact that his kingdom would break apart once he died.[18]

Middle period

Age of disunity

The kingdom formally split into two right after Thihathu’s death in 1325. Saw Yun (r. 1315–27) now controlled the northern country to Tagaung while Uzana I (r. 1325–40) became king of the southern country to Prome and Toungoo. But the control of the southern kingdom was further split between Uzana and Kyawswa. The half-brothers continued to maintain their own military units throughout Central Burma.[19] Kyawswa openly conducted his own policy, for example ordering an attempt on Saw Yun's life.[20]

The rivalry greatly sapped Pinya’s ability to control its own vassals or defend them. Pinya did nothing when Gov. Saw Hnit of Toungoo was assassinated in 1325;[21] Ramanya attacked Prome in 1330;[22] Arakan raided Thayet in 1333–34;[23] or Sagaing raided Mindon in 1339.[24] The rivalry came to a head in 1340. The brothers came close to war but Uzana ultimately backed down.[25][26] He abdicated the throne to Gov. Sithu of Myinsaing, who was also Kyawswa’s father-in-law. Sithu the regent never wielded any power—chronicles do not mention him at all. Though Sithu made an alliance with King Kyaswa of Sagaing (r. 1339–49), Kyawswa never seemed concerned about his father-in-law. According to contemporary inscriptions, he had already declared himself king at least since 1342,[note 6] and became the undisputed ruler in 1344.[27]

Brief return to normalcy

Kyawswa I (r. 1344–50) brought a brief period of unity, at least in the core region. He successfully reunified Pinya's military corps in Central Burma, and formed elite cavalry and shielded infantry units.[28] However, Pinya's hold on more remote places, Toungoo in particular, remained weak. Two Toungoo governors were assassinated in the first three years of his reign. Kyawswa had to be satisfied with the nominal submission by the usurpers.[29] Similarly, his attempt to check the power of the Buddhist clergy was not successful, not least because the court did not fully cooperate.[30] On balance, Kyawswa I brought a much needed period of stability to the country. But he suddenly died in 1350.[27] He is said to have become a nat (spirit) with the name Nga-zi Shin Nat.[31]

Decline

Rapprochement with Sagaing

Pinya struggled to remain relevant after Kyawswa I's death. King Kyawswa II (r. 1350–59) never had much control over the vassals. As a result, he like his father before him tried to regain resources in the core region from the clergy. (His 1359 decree to check on tax-free glebe lands was the earliest extant land survey (sittan) in Myanmar.[27])

One notable change was his Sagaing policy. He agreed to a truce with the northern rival in 1351. Prior to the truce, the relations between them had been worsening with Sagaing having accepted high-level Pinya defections in 1349–51.[note 7] A key driver for the truce may have been the emergence of the Shan state of Maw (Mong Mao), which had fought a successful war against its Mongol overlords (1342–48).[32] After Maw reached a deal with the Mongols in 1355,[32] they turned their attention to their south, launching their first raid into Sagaing territory in 1356. Recognizing the eventual threat to his own realm farther south, Kyawswa II in 1357/58 agreed to an alliance with Sagaing.[33]

Maw raids and Toungoo secession

However, the Pinya king could not fulfill his commitment. His vassals by and large ignored his decree to provide conscripts. Gov. Theingaba of Toungoo outright revolted during the Maw Shan raid of 1358–59, and raided up to Yamethin, 200 km north of Toungoo.[34] Kyawswa II had no response as the Maw forces broke through the Sagaing lines and breached Pinya territory in early 1359. The king died during the raid which ransacked much of his country.[27]

Pinya was now on its last legs. Most of its vassals were practically independent. King Narathu (r. 1359–64) reversed his brother's policy, and broke the alliance with Sagaing.[35] It won no reprieve: Maw forces raided deep into Pinya territory in 1362–63.[27] In desperation, Narathu sought an alliance with the Maw ruler Tho Kho Bwa (r. 1340–71). In 1363, the two rulers agreed to a joint attack on Sagaing, with Pinya as the junior partner.[35] In 1364, they laid siege to the city of Sagaing, with Pinya responsible for a naval blockade. The Maw forces sacked Sagaing in April 1364. But the Maw ruler was unhappy with Pinya's porous blockade, and ordered his forces to attack Pinya across the river. The Maw forces sacked the city in May. The raiders brought the loot and Narathu back to their country.[36]

Fall

The latest Maw invasion left Upper Burma in tatters. Narathu's eldest brother, Uzana II (r. 1364) succeeded the Pinya throne.[37] At Sagaing, a young prince named Thado Minbya (r. 1364–67), a great grandson of Thihathu, seized the throne. Unlike Uzana II, Thado Minbya proved an able and ambitious ruler. He quickly consolidated his hold on the Sagaing vassals, and looked to reunify all of Upper Burma. He took Pinya in September 1364.[38] Over the next six months, he feverishly built a new citadel at a more strategic location at the confluence of the Irrawaddy and the Myitnge in order to defend against the Maw raids. On 26 February 1365, the king proclaimed the foundation of the city of Ava (Inwa), as the capital of the successor state of Pinya and Sagaing kingdoms.[39]

Government

Pinya kings continued to employ Pagan's administrative model of solar polities[6] in which the high king ruled the core while semi-independent tributaries, autonomous viceroys, and governors actually controlled day-to-day administration and manpower.[40][41]

Administrative regions

The court, Hluttaw, was the center of administration, representing at once executive, legislative and judiciary branches of the government.[42] The court administered the kingdom at three general levels: taing (တိုင်း, province), myo (မြို့, town), and ywa (ရွာ, village).[43] Unlike the Pagan government, the Pinya court's reach was limited mainly to the Kyaukse region and its vicinity. The majority of the vassal states reported in the chronicles lay within a 250 km radius from Pinya. Indeed, during the rivalry between Uzana I and Kyawswa I, Pinya did not even control all of the core region.[19] Judging by where Uzana I's battalions were stationed, Pinya's effective power extended no more than 150 km from Pinya.[note 8]

The following table is a list of key vassal states mentioned in the chronicles. Other vassal states listed in the chronicles were Pindale, Pyinsi, Yindaw, Hlaingdet, Kyaukpadaung, Pahtanago, Mindon, Taingda, Mindat, Kanyin, Myaung, Myede, Salin, Paunglaung, Legaing, Salay, Kugan Gyi, Kugan Nge, Ywatha, Talok, Ten tracts of Bangyi, Yaw, Htilin, Laungshay, and Tharrawaddy.[44][45]

| State | Region | Ruler | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pagan (Bagan) | Core | Saw Hnit (1299–1325) | Nominal king (1299–1309) |

| Uzana II of Pagan (1325–68) | Viceroy | ||

| Myinsaing | Core | Sithu (1310–44) Shwe Nan Shin (c. 1344–90?) |

|

| Mekkhaya | Core | No rulers reported after Yazathingyan | |

| Pinle | Core | Kyawswa I (1313–44) Nawrahta (1344–49) Min Letwe (1349–60s?) |

Thihathu proclaimed himself king on 20 October 1309. Nawrahta defected to Sagaing in 1349. |

| Sagaing | Core | Saw Yun (1314–25) | In revolt (1315–17); Independent 1325 onwards |

| Paukmyaing | Core | Min Pale (1347–60s) | |

| Lanbu | Core | Yandathu (1340s)[46] | |

| Wadi | Core | Thinkhaya (c. 1344–?)[46] | |

| Yamethin | Mid | Thihapate (1330s–51) Swa Saw Ke (1351) Thilawa (1351–95/96) |

|

| Shisha | Mid | Nawrahta (1313–44) | |

| Taungdwin | Mid | Thihapate I (1310s–50s)[47] Thihapate II (c. 1350s–67) |

|

| Nyaungyan | Mid | Saw Mon Nit (c. 1344–?)[46] Gonandarit (1350s?)[48] Baya Kyawthu (1360s)[49] |

|

| Sagu | Mid | Theinkhathu Saw Hnaung (c. 1360s–90s) | |

| Thayet | South | Min Shin Saw (1300–34; 1344–50s?) | |

| Prome (Pyay) | South | Kyaswa (c. 1305–44) Saw Yan Naung (1344–1377/78) |

|

| Toungoo (Taungoo) | South | Thawun Gyi (1279–1317) Thawun Nge (1317–24) Saw Hnit (1324–25) Kayin Ba (1325–42) Letya Sekkya (1342–44) Htauk Hlayga (1344–47) Theingaba (1347–67) (in revolt (1358–67)) |

Rulers assassinated (1317, 1325, 1344, 1347); In revolt 1358–67 |

Size

At its founding, Pinya under Thihathu controlled much of Upper Burma from Tagaung to Tharrawaddy. The approximate area would be at least 140,000 km².[note 9] The kingdom's nominal claim became about 100,000 km² after the Sagaing secession in 1325, and about 80,000 km² after the Toungoo secession in 1358.

Military

Pinya was a military weakling. Thihathu claimed to have controlled at least 20,000 troops.[50] But after Thihathu, the Pinya military was divided between Uzana I and Kyawswa I, who maintained their own militias. Uzana I's special military units totaled just 640 shielded knights, 1040 cavalry, and 300 archers.[19] Kyawswa I reunified the army but later Pinya kings never controlled a large enough force to make a difference. Local militias thrived especially after the collapse of Pinya such as in Sagu, Taungdwin and Toungoo.[note 10]

Historiography

Most royal chronicles treat Myinsaing-Pinya as a single period, and Sagaing as a junior branch of the Myinsaing dynasty.

| Item | Zatadawbon Yazawin | Maha Yazawin | Yazawin Thit | Hmannan Yazawin | Inscriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of dynasty | Pinya dynasty[51] | no specific name | Pinya dynasty[52] | Myinsaing−Pinya dynasty[7] | |

| Start of dynasty | 1300/01[51] | 1300/01[53] | 1312/13[54] | 1298/99[55] | 17 December 1297 (of Myinsaing)[56] |

| Thihathu's proclamation as king | 1309/10[57] | 1309/10[53] | 1309/10[58] | 1309/10[59] | 20 October 1309[4] |

| Foundation of Pinya | 7 February 1313[57] | 1312/13[53] | 1312/13[54] | 7 February 1313[7] | |

| Sagaing secession (de facto) |

1322/23[51] | 1322/23[60] | 15 May 1315[61] | 15 May 1315[62] | 26 March 1316[14] |

| Sagaing secession (de jure) |

1323/24[60] | before 30 April 1322[63] | before 30 April 1322[64] | before 29 March 1325[note 11] | |

| Fall of Pinya to Maw Shans | 1364[65] | May 1364[66] | 1364[67] | May 1364[37] | |

| Fall of Pinya to Sagaing | not mentioned | September 1364[66] | 1364[68] | September 1364[69] | |

| End of dynasty | 26 February 1365[70] | 26 February 1365[66] | 26 February 1365[71] | 26 February 1365[72] | before 8 July 1365[note 12] |

Notes

- ↑ Most main royal chronicles treat Myinsaing and Pinya periods as the single dynasty that followed Pagan in Upper Burma. See (Zata 1960: 43), (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 259), and (Hmannan 2003: 363). Only one main chronicle (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 158–159) treats Pinya as a separate period.

- ↑ Chronicles (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 263; Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 376) claim as far south as Tharawaddy.

- ↑ (Harvey 1925: 111): The brothers, when they were Pagan generals, did try to retake Lower Burma in 1293–94 but failed.

- ↑ After all, Thihathu had given himself royal titles in 1295, 1296, and 1306 per (Than Tun 1959: 122).

- ↑ (Than Tun 1959: 123): Athinkhaya died on 13 April 1310. The main chronicles before Hmannan all say Yazathingyan died in 674 ME (1312/13): see (Zata 1960: 43), (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 259) and (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 156–157). Hmannan (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 369) in contradiction to the prior chronicles says Yazathingyan died in 665 ME (1303/04) but inscriptional evidence (Than Tun 1959: 123) shows Hmannan is incorrect.

- ↑ (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 166): According to an inscription donated on 17 June 1342 by Kyawswa's chief queen consort Atula Sanda Dewi, Kyawswa had already claimed himself king.

- ↑ Prince Nawrahta in 1349 per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 380) and Gov. Swa Saw Ke in 1351 per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 403).

- ↑ (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 378): Uzana I's troops were stationed at Pinya, Thingyi, Nyaungyan, Kyauksauk, Lanbu, Thindaung and Yet-Khant Kan-Zaunt.

- ↑ Pinya's claims were similar to Ava's although Ava at its peak was larger. See (Lieberman 2003: 26) and (Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin 2012) for Ava's territory at its peak. Pinya's claims covered present-day Mandalay Region (37,945.6 km²), Magway Region (44,820.6 km²), about half of Bago Region (39,402.3/2 = 19701 km²) and about Sagaing Region (93,704/2 = 46,852 km²), or a total area about 150,000 km².

- ↑ See Thado Minbya's campaigns against Sagu, Taungdwin and Toungoo in (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 398–400)

- ↑ Derived from Uzana I's succession. Per (Than Tun 1959: 123, 127), Uzana I came to power in late 686 ME. 687 ME began on 29 March 1325.

- ↑ (Taw, Forchhammer 1899: 8; Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 182, footnote 2): Per the inscription dedicated at the Shwezigon Pagoda by King Thado Minbya himself on 8 July 1365 (Tuesday, 5th waxing of Waso 727 ME), he was already of king of Ava.

References

- ↑ Than Tun 1959: 119−120

- ↑ Htin Aung 1967: 74

- ↑ Than Tun 1959: 121−122

- 1 2 Than Tun 1959: 122

- ↑ Htin Aung 1967: 75

- 1 2 Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin 2012: 109

- 1 2 3 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 370

- ↑ Lieberman 2003: 120

- ↑ Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin 2012: 94

- ↑ Lieberman 2003: 121

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 370–371

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 374

- ↑ Harvey 1925: 79

- 1 2 Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 161, fn-3

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 373–376

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 160, fn#1

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 372

- ↑ Htin Aung 1967: 76−77

- 1 2 3 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 378

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 383

- ↑ Sein Lwin Lay 2006: 21

- ↑ Phayre 1967: 66

- ↑ Sandamala Linkara Vol. 1 1997: 180

- ↑ Than Tun 1959: 127

- ↑ Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 265

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 379

- 1 2 3 4 5 Than Tun 1959: 124

- ↑ MSK Vol. 2 1955: 22

- ↑ Sein Lwin Lay 2006: 22

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 381

- ↑ MSK Vol. 13 1973: 412

- 1 2 Than Tun 1964: 278

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 384–385

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 334, footnote 3

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 392

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 385

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 393

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 393–394

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 396, 398

- ↑ Lieberman 2003: 35

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 1985: 99–101

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 1985: 130–131

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 1985: 104–105

- ↑ Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 263

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 376

- 1 2 3 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 382

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 400

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 380

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 405

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 373

- 1 2 3 Zata 1960: 43

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 158

- 1 2 3 Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 259

- 1 2 Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 159

- ↑ Hmannan 2003: 363

- ↑ Than Tun 1959: 119

- 1 2 Zata 1960: 42

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 162

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 369

- 1 2 Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 262

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 161

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 375

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 173

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 389

- ↑ Zata 1960: 42−43

- 1 2 3 Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 275

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 170

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 177

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 394

- ↑ Zata 1960: 44

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 181

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 396

Bibliography

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (1985). Pagan: The Origins of Modern Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-0960-2.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael A.; Maitrii Aung-Thwin (2012). A History of Myanmar Since Ancient Times (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-1-86189-901-9.

- Burma Translation Society, ed. (1955). Myanma Swezon Kyan (in Burmese). 2 (1 ed.). Heartford, Heartfordshire: Stephen Austin & Sons, Ltd.

- Burma Translation Society, ed. (1973). Myanma Swezon Kyan (in Burmese). 13 (1 ed.). Yangon: Sarpay Beikman.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Kala, U (1724). Maha Yazawin (in Burmese). 1–3 (2006, 4th printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Maha Sithu (1798). Myint Swe (1st ed.); Kyaw Win and Thein Hlaing (2nd ed.), ed. Yazawin Thit (in Burmese). 1–3 (2012, 2nd printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

- Royal Historians of Burma (c. 1680). U Hla Tin (Hla Thamein), ed. Zatadawbon Yazawin (1960 ed.). Historical Research Directorate of the Union of Burma.

- Royal Historical Commission of Burma (1832). Hmannan Yazawin (in Burmese). 1–3 (2003 ed.). Yangon: Ministry of Information, Myanmar.

- Sandamala Linkara, Ashin (1931). Rakhine Razawin Thit (in Burmese). 1–2 (1997–1999 ed.). Yangon: Tetlan Sarpay.

- Sein Lwin Lay, Kahtika U (1968). Mintaya Shwe Hti and Bayinnaung: Ketumadi Taungoo Yazawin (in Burmese) (2006, 2nd printing ed.). Yangon: Yan Aung Sarpay.

- Taw, Sein Ko; Emanuel Forchhammer (1899). Inscriptions of Pagan, Pinya and Ava: Translation, with Notes. Archaeological Survey of India.

- Than Tun (December 1959). "History of Burma: A.D. 1300–1400". Journal of Burma Research Society. XLII (II).

- Than Tun (1964). Studies in Burmese History (in Burmese). 1. Yangon: Maha Dagon.