Kliegl Brothers Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company

Company logo from the 1922 catalog | |

| Industry | Stage lighting |

|---|---|

| Founded | New York City, United States (1896) |

| Founder | Anton Kliegl, Johann Kliegl |

| Defunct | 1996 |

| Headquarters | Manhattan, New York City, United States |

| Products | Electric stage lighting products |

| Parent | Myerhofer Electric Stage Lighting Company |

| Website |

klieglbros |

Kliegl Brothers Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company was an American manufacturer of electrical stage lighting products in the 20th century. The company had a significant influence in the development of theatrical, cinema, television, and specialty lighting. It equipped many major performing venues in the United States and its products were used in several other countries as well. Their eponymous product, the Klieglight, was the trade name for two quite different production lights manufactured by the company, and survives today in both industry argot and in popular idiom as a synonym for "spotlight" or "center of attention".[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

History

Origins

The company was founded in 1896 in New York City when a Bavarian immigrant, Anton Kliegl, in partnership with A. H. Guendel, purchased the Myerhofer Electric Stage Lighting Company, and renamed it the Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company.[10] A year later his older brother Johann Kliegl replaced Guendel, and the firm became known as the Kliegl Brothers Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company. From its infancy as a firm so small that its proprietors also worked as stagehands to supplement their income,[11] it grew to be one of the largest firms in North America manufacturing lighting and control equipment for the theatre and television stage.

Factories

In the beginning, the firm occupied the Meyerhofer facilities in the old Star Theatre at 842 Broadway, New York City.[12] By 1901 they had moved to 1393-95 Broadway/129 West 38th Street.[13][14] After the loss of this plant to fire on August 15, 1911, they moved again, this time to 240 West 50th Street,[14] and in September 1921, they built and occupied their own four-story plus basement factory at 321-325 West 50th Street.[15] In 1962 they moved to a new, modern two-story plant at 32-32 48th Avenue in Long Island City. By 1966 an annex had been opened two blocks away to meet the press of business. By 1966 "NY/LA" appeared on drawing title blocks, denoting their last expansion, the opening of a branch sales/engineering office in Los Angeles under George Howard. By 1979 "LA" had vanished from the title blocks.[16] After 1980, the company's business began to decline, and by 1990 they had moved to a smaller plant at 5 Aerial Way, Syosset, Long Island, New York.[17] By 1996, the bankrupt company had closed down.

Management

Johann Kliegl was born in Bad Kissingen, Bavaria, Germany in 1869, and his brother Anton in 1872.[18][19][20][21][22] Johann, trained as a locksmith, emigrated to the United States in 1888, and Anton, trained as a plumber, followed him there in 1893. There they both started working in a factory which manufactured electric arc lamps.

Throughout their lives, the two brothers maintained close ties to Bad Kissingen, and endowed there a school, still extant, and grown to encompass grade, middle and high school divisions.[23] Many of their employees were brought over from Bad Kissingen, such that the "patois" on the factory floor was known to the staff as "50th Street Deutsch". Anton, in fact, died in Bad Kissengen on May 19, 1927.[22]

Management was retained by the Kliegl family throughout the history of the firm. Johann remained active until a few days prior to his death on September 30, 1959.[21] His son, Herbert Kliegl, was by that time the managing head of the firm, and remained so until a few weeks before his death on October 3, 1968.[24] Control then passed to Herbert's son John H. Kliegl II. By 1992 the firm was in Chapter 11,[25] and an investment broker, Richard Davisson, took complete ownership and control, replacing John Kliegl II with Al Vitale.[17][26] The firm ceased operations in November 1996.[27]

Products

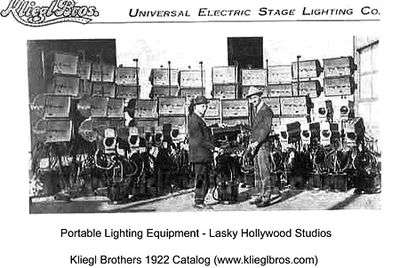

At the time of the firm's founding, electric lighting for the stage was in its infancy. Held finds no catalog of stage lighting equipment earlier than Kliegl's catalog of 1898.[28] as cited in Rubin[29]page 72, note 39. Indeed, it may be inferred that the use of "Electric" in the company's name was intended to distinguish its products from the illuminating gas or acetylene fueled equipment they would replace. Many of what became common devices, such as the stage "shoe" or thrust plug and the disappearing footlight were patented by the Kliegls, and many others were developed into the forms still familiar today[30][31] Initially they continued the Myerhofer business as "contractors and manufacturers", as noted in their Catalog G of 1913.[32] In 1903 they furnished and installed the complete stage lighting system for the Metropolitan Opera Company's new home on West 37th Street (John was at the time an electrician for the Met).[29][33]page93 In 1933 they would be again called to provide a complete new stage lighting system, although not as installers. Catalog G also displayed the carbon arc floodlight, developed by the firm in 1911, as the iconic Klieglight. A diverse assortment of lighting and electrical products were also cataloged, such as exit signs, backup batteries, dimmer boards, connectors, effect projectors, chandeliers, marquee lights (and complete marquees), charging outlets for electric cars, switchboards, etc. Featured was a "Skyrocket" sign for Tilyou's Steeplechase Park in Coney Island.[34] The development of electrical standards was spurred, in part, by the Iroquois Theatre fire of 1903. Kliegl Brothers' Catalog E states that "plugs and receptacles are in accordance with Underwriter's requirements and pass city inspections"[29]page 10. The Kliegls maintained a direct interest in the development of standards for theatre electrical systems. From 1950 to his death, Herbert Kliegl was a member of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) code making panel No. 115.[35] A precursor of today's spotlights, the "baby spotlight", their first using an incandescent lamp, was introduced in their Catalog E of 1906[33] as cited in Rubin [29]page 84. The takeover of the incandescent lamp would be inexorable.[36][37] as cited in Rubin [29]page93, note 66 From about 1908, motion picture studios were using the company's floor-stand arc lamps, which allowed for point-source lighting, including some of the first low-light effects; the shadow produced by the two pairs of carbon rods can be seen in some early films.[38] In their 1922 catalog, the company was still featuring its motion picture studio equipment, but by 1926, references to motion picture applications had dwindled to a single line of type on the first page.[32] In 1924 they introduced the use of glass rondels as color media in border and footlights, eliminating coloring of individual lamps.[39] Kliegl Brothers introduced its Fresnel lens spots in 1929, and by 1935 were ordering their own Fresnel lenses from Corning.[33] as cited in Rubin[29]page 171

Pages devoted to Kliegl products in the 1928/29 catalogs of retailers such as Holzmueller on the west coast and wholesalers like Marle in Stamford, Connecticut, showed that their sales now extended well beyond their own factory.[32] The condensed catalog of 1929 for the first time lists a broader range of "Mazda" (incandescent lamps) than arc spots.[32] By 1930, the "Mazda" name has vanished, yielding to "incandescents".

In 1932, the Kliegl brothers installed their new ellipsoidal reflector spotlights in the Center Theatre in Radio City.[40] Based on the new GE T14 medium bipost lamps, these had triple the efficiency of the standard plano convex spots. They were demonstrated to a meeting of the Illuminating Engineering Society on April 19, 1933[29]page 186 and introduced as a standard product in Catalog B of 1933 as "Klieglights" [29]page 187, note 75 and billed on pages 42–45 of Catalog 40 of 1936 as "The New Klieglight".[32]

Catalog 40 of 1936 introduced a full line of architectural downlights (individual architectural products had been made for some time), the autotransformer dimmer (originally dubbed the "Transtat", the catalog was overstamped, changing the trade name to "Autrastat"), motor operated dimmers, fresnel lens spots, etc. At the same time, the more obsolete and exotic products began to disappear.[32]

This catalog also introduced "Alzak" reflectors, Alzak being a proprietary process for producing a mirror-like finish on aluminium. Under agreement with the process owner, Alcoa, Kliegl Brothers created reflectors using the Alzak process for their own use and for sale at the Kliegl Reflector Company, a separate subsidiary plant located on 11th Avenue between 33rd and 34th streets (opposite the location of the present Javits Center). Major was the only other licensee for stage lighting reflectors.[29]page 205

An interesting specialty, prominently featured in this catalog, but dating to the first catalog, was the effect projector, in which rotating, hand painted, transparent discs rotated before projector spots. Precise optical lenses spread the image to beam lighted patterns or images, ranging from a simple snowfall to the elaborate "Christ Rising to Heaven with Three Angels", onto a stage backdrop. Six artists sat before the tall 50th Street windows on the third floor hand painting the tiny images which would be magnified many times when in use.[29]pagees 10-11 These were used not only on stage, but also in architectural applications.[41] By 1960, effect projectors had been made obsolete by film, and later, computer-generated projections.

By catalog T61, issued in 1954, the arc spots were represented by a single model, while the Klieglight line offered models ranging from 250 watt to 3000 watt spots.[32] The company was also offering their "Dynabeam" lensed follow spot, and fresnels from 100 to 2000 watts. In that era of patch panels and small numbers of high wattage dimmers, Kliegl Brothers offered its "Safpatch" patch panels, and "Rotolector" rotary power switches, both developed by Herbert Kliegl. Both products interlocked the electrical contacts with a circuit breaker, preventing arcs while switching or patching.[42][43][44] From the beginning of the firm's operations, custom products were readily available. Indeed, the craft shop system used throughout its history made little differentiation between custom and standard products. High-end lighting designers regularly sought out Kliegl Brothers, who could design and produce the hardware that would fulfill their visions. Often, the custom product made its mark on the industry, such as the wall washers designed for the UN General Assembly room, or the fluorescent wall washers for New York's Pan American (now Met Life) building lobby, both designed by Herbert Kliegl. A custom oddity was the scoreboard designed for Madison Square Garden, across 50th Street from the factory. This remained in use until the relocation of the Garden to its current home atop Penn Station.

Until 1959 Kliegl provided controls as an assembler of equipment purchased or licensed from others. Resistance plates and variable brush autotransformers were largely purchased from Ward Leonard; magnetic amplifiers from General Electric. Thyratron dimmers were manufactured under license from Strand Electric of England.[29] All this started to change in 1958.

In 1959 the first commercially viable solid state theatre dimmer, Kliegl's SCR(R), was introduced as model R59.[45][46] Improved models followed. Within two years, the solid state dimmer had, as a practical matter, swept away all other dimming systems.

In the 1960s, like other theatrical suppliers, the company was making more from amateur theatre companies than from either film or professional theatre.[47] In 1977, the company received permission to start a Toronto subsidiary.[48] But by the 1978 series of catalog brochures, product development had significantly slowed down.[32] An attempt to build a modern control console had failed, and the control systems had been largely outsourced. Luminaire and accessory lines had further narrowed, and the trend was inexorable. Unable to compete in a world of low-cost mass production, the firm finally ceased operations in 1996.

Klieglight

The first "Klieglight" was a powerful carbon arc light designed for the motion picture industry.[49] It was not the first arc light offered by the company (arc floods are offered in their bulletin "Stage Lighting Apparatus and Effects of Every Description", published prior to 1906), and nor was it a spotlight.[50] Its first listing is in Catalog G of 1913, where it is shown as a horizontal wide flood.[32] None of the surviving catalogs, through to its disappearance from the company's product line, describe any other lighting instrument as a "Klieglight", with all arc spotlights uniformly described as "arc spotlights". "Klieglight", however, reappears on pages 42–45 of Catalog 40 of 1936 as the name of their new line of ellipsoidal reflector incandescent spotlights, and this usage continued as long as the company was in existence.[32] Oddly enough, the company apparently did not attempt to trademark the name, although there was a filing for a logo that was never carried through.[51]

Major projects

The following is a representative sampling of major projects undertaken by Kliegl Brothers:

- Metropolitan Opera at 37th Street, New York City (1903 and 1933); replacements thereafter[29]

- Roxy Theatre, stage lighting[32]

- CEA Movie Studios, Madrid, Spain[32]

- Madison Square Garden at 50th Street, NYC[32]

- Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center, architectural lighting

- Radio City Music Hall (1932; equipment replaced 1963)[52]

- Jones Beach Marine Theatre

- 666 5th Avenue, New York City, exterior lighting

- RCA Building at Rockefeller Center, exterior lighting

- Philharmonic Hall, (Avery Fisher Hall) Lincoln Center, architectural lighting (1962)

- Place des Arts, Montreal (1963)

- New York State Theatre, Lincoln Center (1964)

- Los Angeles Music Center (1965) [16]

- CBS Studios 31 & 3, Los Angeles (1967, 70)[16]

- Moscow World Trade Center (1971)[16]

- ABC TV 66th and 67th Street Studios, New York City

- NBC TV studios, Hollywood

- Teatro Teresa Careno, Caracas, Venezuela

- State Opera House (Staatsoper), Vienna, Austria

- Ernie Pyle Theatre, Tokyo, Japan

References

- ↑ Morgan, Frederick; Hellman, Geoffrey (July 13, 1957). "Kleig-Light Kleigl". The New Yorker. New York City. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ Klages, Bill (January 5, 2012). "What's a Klieg Light?". TV Technology. NewBay Media. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Klieg light". Thesarus.com. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Klieg light". Wordsmith.org. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "The Klieg Light Magazine". Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Klieg Magazine". Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Dimming The Klieg Lights On Drama Queens And Kings". Etiquette Hell. May 16, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "THE CONGRESS: Duel under the Klieg Lights". Time Magazine. New York City: Time Inc. August 18, 1947. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ Gallo, Bill (December 21, 2000). "Klieg Lights in Vermont". Phoenix New Times. Phoenix, Arizona: Kurtis Barton. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Item 2". Dr. Joel E. Rubin Collection. Ohio State University: Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Library.

- ↑ "Kliegl Brothers". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

Lists 16 shows produced between 1901 and 1917 with the Kliegl Brothers listed as either stage electrician or lighting designer.

- ↑ "Earliest published catalog". Dr. Joel E. Rubin Collection. Ohio State University: Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Library. 1898.

- ↑ "Catalog". Dr. Joel E. Rubin Collection. Ohio State University: Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Library. 1902.

- 1 2 "Advertisement sheet". Dr. Joel E. Rubin Collection. Ohio State University: Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Library. February 17, 1912.

- ↑ The New York Times. New York City, New York. August 17, 1920. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Theatre Lighting Drawings Collection. Kliegl Brothers Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company.". Rare Books and Manuscripts, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, 104 Paterno Library. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Libraries.

- 1 2 Broadcasting Yearbook

- ↑ Wulz, Gerhard (2001). Der Kapellenfriedhof in Bad Kissingen. Ein Führer mit Kurzbiografien [The Chapel Cemetery in Bad Kissingen. A guide with short biographies] (in German). Verlag Stadt Bad Kissingen. ISBN 3-934912-04-4.

- ↑ "Die Kliegl-Brüder: Anton Tiberius & Johann Hugo Kliegl". Website of the city of Bad Kissingen. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ "Kissengen's Favorite Son". Liederkranz News. New York: Liederkranz Club. 6 (9). June 1958.

- 1 2 "Obituary of Johann Kliegl". The New York Times. New York City, New York. October 1, 1959.

- 1 2 "Obituary of Anton Kliegl". The New York Times. New York City, New York. May 21, 1927.

- ↑ "Anton-Kliegl-Mittelschule Bad Kissingen". Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Obituary of Herbert Kliegl". The New York Times. New York City, New York. October 9, 1968.

- ↑ West's New York digest, 4th. 5, part 2. West. 2008.

- ↑ Re Kliegl Bros. (238 BR 531 – Bankr. Court, ED New York 1999). Text

- ↑ New York Department of State

- ↑ Held, McDonald Watkins (1955). "A History of Stage Lighting in the United States in the Nineteenth Century". Doctoral dissertation. Northwestern University.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Rubin, Joel Edward (1960). "The technical development of stage lighting apparatus in the United States, 1900-1950". Doctoral dissertation. Stanford University.

- ↑ US 963733, Kliegl, John H., "Plug-switch", published July 22, 1907, issued July 05, 1910

- ↑ US 1141122, Kliegl, Anton T., "Stage-footlights", published May 25, 1914, issued June 01, 1915

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Kliegl Brothers Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company Collectors Society". klieglbros.com. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Wild, Larry. "A Brief Outline of the History of Stage Lighting". Aberdeen, South Dakota: Northern State University. Retrieved January 7, 2014.as cited in

- ↑ For illustrations of the company's products from the early era of incandescent lighting, see Izenour, George C. (1996). Theater Technology (2nd ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University. p. 127. ISBN 9780300067668.

- ↑ Archives. National Fire Protection Association.

- ↑ "Replacing the Arc Lamps in Stage Lighting". Electrical Review. LXXI (2). July 14, 1917.

- ↑ "Kliegl Stage Lamp Designed to Use 1000-Watt Gas Filled Lamps". Electrical Record. XXI (2). August 1917.

- ↑ Abel, Richard, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Early Cinema. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. p. 385. ISBN 9780415234405.

- ↑ "Detachable color globes: A new feature embodied in stage lighting equipment". Architecture and Building. LVI (1). January 1924.

- ↑ Burris-Meyer, Harold (1949). Theatres & auditoriums. New York: Reinhold Pub. Corp. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ Akron Beacon Journal. Akron, Ohio. October 27, 2002. p. F7. Missing or empty

|title=(help);|section=ignored (help) - ↑ Safpatch, Kliegl, Herbert A., "Trademark serial number 71667038, registration number 0602956", published May 25, 1954, issued March 08, 1955

- ↑ Rotolector, Kliegl, Herbert A., "Trademark serial number 71608009, registration Number 0548015", published December 22, 1950, issued September 11, 1951

- ↑ US 2594181, Kliegl, Herbert A., "Selector switch", published Jul 29, 1950, issued Apr 22, 1952

- ↑ Brightness Controls for Electrical Lighting, Kliegl, Herbert A., "Trademark serial number 72063321, registration number 0694481", published November 28, 1958, issued March 15, 1960

- ↑ US 2920240, Sutherland, Macklem F, "Theater lighting control system", published Dec 8, 1958, issued Jan 5, 1960

- ↑ Dusseault, Norm (June 10, 1962). "Cuelines: Amateur theatre is big—and it's getting bigger". St. Petersburg Times.

- ↑ "FIRA approves sale of two clothing firms". The Montreal Gazette. July 8, 1977.

- ↑ "Definition of klieg light". Merriam-Webster dictionary. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Item 11". Dr. Joel E. Rubin Collection. Ohio State University: Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Library.

- ↑ Filing for logo. Serial number 73595071, April 24, 1986

- ↑ The New York Times. New York City, New York. December 25, 1932. Missing or empty

|title=(help)