Konkani people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 7.4 million[1] (2007) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Karnataka | 706,397[2] |

| Goa | 602,606[2] |

| Maharashtra | 522,000 |

| Kerala | 113,432[3] |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 27,000 |

| Languages | |

| Konkani (Including Katkari, Varli, Kadodi, Phudagi and Kukna) | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism, Christianity, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryans · Kannadigas · Tuluvas · Marathis | |

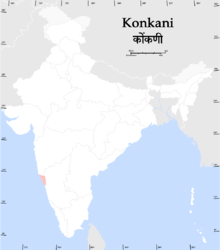

The Konkani people (Koṅkaṇī lok also Koṅkaṇe, Koṅkaṇstha) are a linguistic community found mainly in the Konkan Coast of south western India whose mother-tongue is the Konkani language. They originate from coastal Karnataka and Goa.

The word Konkan and, in turn Konkani, is derived from Kuṅkaṇ or Kuṅkaṇu. Different authorities explain etymology of this word differently. Some include:

- Koṇ meaning top of the mountain.

- Name of aboriginal mother goddess, which is sometimes sanskritised to mean goddess Renuka.

Thus the name Konkane, comes from the word Konkaṇ, which means the people of Konkan.[4]

The Konkani people speak different dialects of Konkani, their native tongue; although a very high percentage are bilingual.[5]

Denominations

Endonyms

In general, in Konkani the masculine form used to address a fellow Konkani speaker is Koṅkaṇo and the feminine form is Koṅkaṇe. The plural form is Konkane or Konkani. In Goa Konkano now refers only to Hindus, and Catholic Goans do not address themselves as Konkanos as they were banned by the Portuguese from referring to themselves this way. Saraswat Brahmins of Canara refer to the Konkanis as Āmcigelo /Āmcigelī. This literally means our tongue or people speaking our tongue. Though this is not common amongst the Goans, they normally refer to Konkani as Āmgelī bhās or our language. Sometimes Āmgele can be used in the Goan context to mean people from my community.

Exonyms

A Konkani person is normally referred to as a Konkaniga in Kannada (Census of India, 1891). Many of the colonial documents mention them as the Concanees, Canarians, Concanies.[6][7]

History

Prehistory

The then prehistoric region consisting of Modern Goa and some parts of Konkan adjoining Goa were inhabited by the Homo sapiens in Upper paleolithic and Mesolithic phase i.e. 8000–6000 BC. The rock engraving in many places along the coast has proven the existence of hunter-gathers.[8] Nothing much is known about these earliest settlers. Figures of Mother goddess and many other motifs have been recovered which do not really shed light on the ancient culture and language.[9] Traces of Shamanic culture have been found in Goa.[10]

It is believed that tribes of Austric origin like Kols, Mundaris, Kharvis may have settled Goa and Konkan during the Neolithic period, living on hunting, fishing and a primitive form of agriculture since 3500 BC.[11] According to Goan historian Anant Ramakrishna Dhume, the Gauda and Kunbi and other such castes are modern descendants of ancient Mundari tribes. In his work he mentions several words of Mundari origin in the Konkani language. He also elaborates on the deities worshiped by the ancient tribes, their customs, methods of farming and its overall impact on modern day Konkani society.[12] The Negroids were in an Neolithic stage of primitive culture, and they were food-gatherers rather. Traces of Negroid physical characteristics are found in parts of Goa, at least up to the middle of the first millennium.[12] The Proto-Australoid tribe known as the Konkas, from whom is derived the name of the region, Kongvan or Konkan with the other mentioned tribes formed reportedly the earliest settlers in the territory.[13] Agriculture was not fully developed at this stage, and was just shaping up. The Kols and Mundaris might have been using stone and wood implements as iron implements were used by the megalithic tribes as late as 1200 BC. The Kol tribe is believed to have migrated from Gujarat.[14] During this period worship of mother goddess in the form of anthill or Santer, was started. Anthill is called as Roen (Konkani:रोयण), this word has been derived from the austric word Rono meaning with holes. The later Indo-Aryan and Dravidian settlers also adopted anthill worship, which was translated to Santara in Prakrit by them.[12]

The later period

The first wave of Vedic people came and settled from Northern India in then Konkan region about 2400 BC. Some of them might have been followers of Vedic religion.[18] They were known to speak earliest form of Prakrit or Vedic Sanskrit vernacular. This migration of the northerners is mainly attributed to the drying up of the Sarasvati River in Northern India. Many historians claim only Gaud Saraswat Brahmins and few of the other Brahmins to be their descendants. This hypothesis is not authoritative according to some. Balakrishna Dattaram Kamat Satoskar a renowned Goan Indologist and historian, in his work Gomantak prakruti ani sanskruti, Volume I explains that the original Sarasvat tribe consisted of people of all the folds who followed the Vedic fourfold system and not just Brahmins, as the caste system was not fully developed then, and did not play an important role.(see Gomantak prakruti ani sanskruti,Volume I).

The second wave of Indo-Aryans occurred sometime between 1700 to 1400 BC. This second wave migration was accompanied by Dravidians from the Deccan plateau. A wave of Kusha or Harappan people a Lothal probably around 1600 BC to escape submergence of their civilisation which thrived on sea-trade.[10] The admixture of several cultures, customs, religions, dialects and beliefs, led to revolutionary change in the formation of early Konkani society.[18]

The classical period

The Maurya era is marked with migrations from the East, advent of Buddhism and different Prakrit vernaculars.[19] Greeks settled Goa during the Satavahana rule, similarly a mass migration of Brahmins happened from the north, whom the kings had invited to perform Vedic sacrifices.

The advent of Western Satrap rulers also led to many Scythian migrations, which later gave its way to the Bhoja kings. According to Vithal Raghavendra Mitragotri, many Brahmins and Vaishyas had come with Yadava Bhojas from the North (see A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara). The Yadava Bhojas patronised Buddhism and settled many Buddhist converts of Greek and Persian origin.[20]

The Abhirs, Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Shilaharas ruled the then Konkan-Goa for several years which was responsible for many changes in the society.Later The powerful Kadambas of Goa, came to power. During their rule,the society underwent radical transition. Close contact with the Arabs, Turks, introduction of Jainism, patronising Shaivism, use of Sanskrit and Kannada, the overseas trade had an overwhelming impact on the people.

13th–19th century AD

Turkic rule

In 1350 CE, Goa was conquered by the Bahmani Sultanate of Turkic origin. However, in 1370, the Vijayanagar Empire, a resurgent Hindu empire situated at modern day Hampi, reconquered the area. The Vijayanagar rulers held on to Goa for nearly 100 years, during which its harbours were important landing places for Arabian horses on their way to Hampi to strengthen the Vijaynagar cavalry. In 1469, however, Goa was reconquered, by the Bahmani Sultans. When this dynasty broke up in 1492, Goa became a part of Adil Shah's Bijapur Sultanate, who made Goa Velha their second capital. The Bahamanis demolished many temples, and forced the Hindus to convert to Islam. To avoid this religious persecution, several Goans families fled to the neighbourhood kingdom of Soonda.[21]

Portuguese rule

The Portuguese Conquest of Goa occurred in 1510 on behalf of the Portuguese admiral Afonso de Albuquerque. Goa (also Old Goa or Velha Goa) was not among the cities Albuquerque had received orders to conquer: he had only been ordered by the Portuguese king to capture Hormuz, Aden and Malacca.[22] Goa Inquisition was established in 1560, briefly suppressed from 1774–1778, and finally abolished in 1812.[23] The Goan Inquisition is considered a blot on the history of Konkani people and Goa. Its ostensible aim was to preserve the Catholic faith, the Inquisition's beginning in 1561 and its temporary abolition in 1774, some 16,202 persons were brought to trial by the Inquisition. Of this number, it is known that 57 were sentenced to death and executed in person; another 64 were burned in effigy. Others were subjected to lesser punishments or penanced, but the fate of many of the Inquisition's victims is unknown.[24]

The inquisitor's first act was to forbid any open practice of the Hindu faith on pain of death. Sephardic Jews living in Goa, many of whom had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape the excesses of the Spanish Inquisition to begin with, were also persecuted.[25] Seventy-one autos da fe were recorded. In the first few years alone, over 4000 people were arrested.[25] In the first hundred years, the Inquisition burnt at stake 57 alive and 64 in effigy, 105 of them being men and 16 women. Others sentenced to various punishments totalled 4,046, out of whom 3,034 were men and 1,012 were women.[26] According to the Chronista de Tissuary (Chronicles of Tiswadi), the last auto da fe was held in Goa on 7 February 1773.[26]

According to Indo-Portuguese historian Teotonio R. de Souza, grave abuse was practised in Goa in the form of 'mass baptism' and what went before it. The practice was begun by the Jesuits and was later initiated by the Franciscans also. The Jesuits staged an annual mass baptism on the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul (25 January), and to secure as many neophytes as possible, a few days before the ceremony the Jesuits would go through the streets of the Hindu quarter in pairs, accompanied by their slaves, whom they would urge to seize the Hindus. When the slaves caught up to a fugitive, they would smear his lips with a piece of beef, making him an 'untouchable' among his people. Conversion to Christianity was then his only option.

The inquisition was set as a tribunal, headed by a judge, sent to Goa from Portugal and was assisted by two judicial henchmen. The judge was answerable to no one except to Lisbon and handed down punishments as he saw fit. The Inquisition Laws filled 230 pages and the palace where the Inquisition was conducted was known as the Big House and the Inquisition proceedings were always conducted behind closed shutters and closed doors.

According to the historian, "the screams of agony of the victims (men, women, and children) could be heard in the streets, in the stillness of the night, as they were brutally interrogated, flogged, and slowly dismembered in front of their relatives. "Eyelids were sliced off and extremities were amputated carefully, a person could remain conscious even though the only thing that remained was his torso and head.[27]

Fr. Diago de Boarda and his advisor Vicar General, Miguel Vaz had made a 41-point plan for torturing Hindus. Under this plan Viceroy António de Noronha issued in 1566, an order applicable to the entire area under Portuguese rule:[27]

I hereby order that in any area owned by my master, the king, nobody should construct a Hindu temple and such temples already constructed should not be repaired without my permission. If this order is transgressed, such temples shall be, destroyed and the goods in them shall be used to meet expenses of holy deeds, as punishment of such transgression.

In 1567, the campaign of destroying temples in Bardez met with success. At the end of it 300 Hindu temples were destroyed. Enacting laws, prohibition was laid from 4 December 1567 on rituals of Hindu marriages, sacred thread wearing and cremation.[27]

All the persons above 15 years of age were compelled to listen to Christian preaching, failing which they were punished. In 1583 Hindu temples at Assolna and Cuncolim were destroyed through army action.[27]

"The fathers of the Church forbade the Hindus under terrible penalties the use of their own sacred books, and prevented them from all exercise of their religion. They destroyed their temples, and so harassed and interfered with the people that they abandoned the city in large numbers, refusing to remain any longer in a place where they had no liberty, and were liable to imprisonment, torture and death if they worshipped after their own fashion the gods of their fathers." wrote Filippo Sassetti, who was in India from 1578 to 1588.[27]

An order was issued in June 1684 eliminating the Konkani language and making it compulsory to speak the Portuguese language. The law provided for dealing toughly with anyone using the local language. Following that law all the symbols of non-Christian sects were destroyed and the books written in local languages were burnt.[27]

The victims of such inhuman laws of the Inquiry Commission included a French traveller named Charles Delone. He was an eyewitness to the atrocities, cruelty and reign of terror unleashed by priests.[28] He published a book in 1687 describing the lot of helpless victims. While he was in jail, he had heard the cries of tortured people beaten with instruments having sharp teeth. All these details are noted in Charles Dellon's book, Relation de l'Inquisition de Goa (The Inquisition of Goa).[28]

The viceroy ordered that Hindu pandits and physicians be disallowed from entering the capital city on horseback or palanquins, the violation of which entailed a fine. Successive violations resulted in imprisonment.[29]

Christian palaquin-bearers were forbidden from carrying Hindus as passengers. Christian agricultural labourers were forbidden to work in the lands owned by Hindus and Hindus forbidden to employ Christian labourers.[29]

The Inquisition guaranteed "protection" to Hindus who converted to Christianity. Thus, they initiated a new wave of baptisms to Hindus who were motivated by social coercion into converting.[30]

The adverse effects of the inquisition were tempered somewhat by the fact that Hindus were able to escape Portuguese hegemony by migrating to other parts of the subcontinent[31] including to Muslim territory.[32]

Ironically, the Inquisition also had an adverse unintended consequence, in that it was a compelling factor for the emigration of a large number of Portuguese from the Portuguese colonies, who although Roman Catholic by faith, had now acculturated into Hindu culture. These people went on to seek their fortunes in the courts of different Indian kings, where their services were employed, usually as gunners or cavalrymen.[33]

Impact on culture and language

In stark contrast to the earlier intense study of the Konkani language and its cultivation undertaken by the Portuguese priests as a communication medium in their quest for converts during the earlier century, the Inquisition brought about xenophobic measures intended at isolating new converts from the non-Christian populations.[34] This suppression of Konkani was in face of the repeated Maratha onslaughts of the late 17th and earlier 18th centuries, which for the first time posed a serious threat to Goa, and by extension, the Portuguese presence in India itself.[34] The Maratha threat, compounded by their religious zeal, led the Portuguese authorities to initiate a positive programme for the suppression of Konkani in Goa.[34] As a result, the ancient language of Konkani was suppressed and rendered unprivileged by the enforcement of Portuguese.[35] Urged by the Franciscans, the Portuguese viceroy forbade the use of Konkani on 27 June 1684 and further decreed that within three years, the local people in general would speak the Portuguese tongue and use it in all their contacts and contracts made in Portuguese territories. The penalties for violation would be imprisonment. The decree was confirmed by the king on 17 March 1687.[34] However, according to the Inquisitor António Amaral Coutinho's letter to the Portuguese monarch João V in 1731, these draconian measures did not meet with success.[a][36] With the fall of the "Province of the North" (which included Bassein, Chaul and Salsette) in 1739, the assault on Konkani gained new momentum.[34] On 21 November 1745, Archbishop Lourenzo de Santa Maria decreed that to qualify for priesthood, the knowledge of, and the ability to speak only in Portuguese, not only for the pretendentes, but also for all the close relations, men as well as women, confirmed by rigorous examinations by reverend persons was an essential prerequisite.[34] Furthermore, the Bamonns and Chardos were required to learn Portuguese within six months, failing which they would be denied the right to marriage.[34] The Jesuits, who had historically been the greatest advocates of Konkani, were expelled in 1761. In 1812, the Archbishop decreed that children should be prohibited from speaking Konkani in schools and in 1847, this was extended to seminaries. In 1869, Konkani was completely banned in schools.[34]

The result of this linguistic displacement was that Goans did not develop a literature in Konkani, nor could the language unite the population as several scripts (including Roman, Devanagari and Kannada) were used to write it.[35] Konkani became the lingua de criados (language of the servants)[37] as Hindu and Catholic elites turned to Marathi and Portuguese respectively. Ironically, Konkani is at present the 'cement' that binds all Konkanis across caste, religion and class and is affectionately termed Konkani Mai (Mother Konkani).[35] The language only received official recognition in 1987, when on the February of that year, the Indian government recognised Konkani as the official language of Goa.[38]

Konkanis today

The Konkani community, however, rebounded from every setback. With the end of the British and Portuguese Empires in India, the community has made significant strides. Konkanis today are an urbanized community. A large section of the community works in the banking sector, given their background in trade and commerce. However, the community has diversified into various professions and made a name for itself in the industrial, technical and medical fields. A high percentage of Konkanis are now engaged in tertiary occupations as compared to other communities.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ "Konkani". Ethnologue. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Commissioner Linguistic Minorities (originally from Indian Census, 2001)". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007.

- ↑ "Census of India – DISTRIBUTION OF 10,000 PERSONS BY LANGUAGE". Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ↑ Sardessai, Manohar Ray (2000). A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. New Delhi: Sahitya Akedemi. pp. 317, (see chapter I, pages: 1–15). ISBN 9788172016647.

- ↑ Language in India

- ↑ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1859). House of Commons papers, Volume 5 By Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Great Britain: HMSO, 1859.

- ↑ Krishnat P. Padmanabha Menon; Jacobus Canter Visscher (1924). History of Kerala: a history of Kerala written in the form of notes on Visscher's letters from Malabar, Volume 1. Asian Educational Services,. pp. see page 196.

- ↑ Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty, Robert G. Bednarik, Indirā Gāndhī Rāshṭrīya Mānava Saṅgrahālaya (1997). Indian rock art and its global context. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.,. pp. 228 pages (see page 34). ISBN 9788120814646.

- ↑ Goa (India : State). Directorate of Archives and Archaeology, Goa University (2001). Goa in the Indian sub-continent: seminar papers. Goa: Directorate of Archives and Archaeology, Govt. of Goa,. pp. 211 pages (see page 24).

- 1 2 Kamat, Nandkumar. "Prehistoric Goan Shamanism". Prehistoric Goan Shamanism. The navahind times. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ↑ De Souza, Teotonio R. (1994). Goa to me. Concept Publishing Company,. pp. 176 pages (see page 33). ISBN 9788170225041.

- 1 2 3 Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna (1986). The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D. Ramesh Anant S. Dhume. pp. 355 pages (see pages 53, 94, 83, 95).

- ↑ Gomes, Olivinho (1987). Village Goa: a study of Goan social structure and change. S. Chand,. pp. 426 pages.

- ↑ De Souza, Teotonio R. (1989). Essays in Goan history. Concept Publishing Company,. pp. 219 pages (see pages 1–16). ISBN 9788170222637.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=mcuxIsn6wbQC&pg=PA33&dq=bajirao+chitpavan&hl=en&sa=X&ei=0qhVUpX-DM6FrAeqiYDwAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=_g-_r-9Oa_sC&pg=PA400&dq=bajirao+chitpavan&hl=en&sa=X&ei=0qhVUpX-DM6FrAeqiYDwAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=tDRiJ3HZVPQC&pg=PA55&dq=konkani+chitpavan&hl=en&sa=X&ei=46lVUoaKFsb4rQeTkYCIAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- 1 2 Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna (1986). The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D. Ramesh Anant S. Dhume. pp. 355 pages (see pages 100–185).

- ↑ Moraes, Prof. George. "PRE-PORTUGUESE CULTURE OF GOA". Published in the Proceedings of the International Goan Convention. Published in the Proceedings of the International Goan Convention. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ↑ Satoskar, Ba.Da (1982). Gomantak prakruti ani sanskuti,khand II,in Marathi. Pune: Shubhda publishers. p. 106.

- ↑ Karnataka State Gazetteer by Karnataka (India), K. Abhishankar, Sūryanātha Kāmat, Published by Printed by the Director of Print, Stationery and Publications at the Govt. Press, 1990, Page:251

- ↑ Conversions and citizenry: Goa under Portugal, 1510–1610 Délio de Mendonça p.82ff

- ↑ "'Goa Inquisition was most merciless and cruel'". Rediff. 14 September 2005. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ↑ Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001), pp. 345–7.

- 1 2 Hunter, William W, The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Trubner & Co, 1886

- 1 2 Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians, Alan Machado Prabhu, I.J.A. Publications, 1999, p. 121

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Goa Inquisition by Christian Historian Dr. T. R. de Souza

- 1 2 L'Inquisition de Goa: la relation de Charles Dellon (1687)

- 1 2 Priolkar, A. K. The Goa Inquisition. (Bombay, 1961)

- ↑ Shirodhkar, P. P., Socio-Cultural life in Goa during the 16th century, p. 35

- ↑ Shirodhkar, P. P., Socio-Cultural life in Goa during the 16th century, p. 123

- ↑ The Cambridge history of seventeenth-century music, By Tim Carter, John Butt, pg. 105

- ↑ Dalrymple, William, White Mughals (2006), p. 14

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians, Alan Machado Prabhu, I.J.A. Publications, 1999, pp. 133–134

- 1 2 3 Newman, Robert S. (1999), The Struggle for a Goan Identity, in Dantas, N., The Transformation of Goa, Mapusa: Other India Press, p. 17

- ↑ Priolkar, Anant Kakba; Dellon, Gabriel; Buchanan, Claudius; (1961), The Goa Inquisition: being a quatercentenary commemoration study of the inquisition in India, Bombay University Press, p. 177

- ↑ Routledge, Paul (22 July 2000), "Consuming Goa, Tourist Site as Dispencible space", Economic and Political Weekly, 35, Economic and Political Weekly, p. 264

- ↑ Goa battles to preserve its identity – Times of India, 16 May 2010

Bibliography

- Hindu Temples and deities by Rui Pereira Gomes

- Bharatiya Samaj Vighatak Jati Varna Vyavastha by P.P. Shirodkar, published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu: district gazetter by Vithal Trimbak Gune, Goa, Daman and Diu (India). Gazetteer Dept, Published by Gazetteer Dept., Govt. of the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu, 1979

- The Village Communities. A Historical and legal Perspective – Souza de, Carmo. In: Borges, Charles J. 2000: 112 and Velinkar, Joseph. Village Communities in Goa and their Evolution

- Caste and race in India by Govind Sadashiv Ghurye

- The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D By Anant Ramkrishna Sinai Dhume

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Konkani people. |

- History of Konkani Muslims of Costal Maharashtra

- The Kanara Saraswat Association

- About the roots of the Konkani speaking Saraswat Brahmin community

- History of Mangalorean Konkani Christians

- A Welfare organisation of Konkani Muslim or Kokni Muslim in the Gulf

- Daivajna Community Website

- Origins of Konkani Language

- Online Manglorean Konkani Dictionary Project