Kunlun Mountain (mythology)

- This article is about the mythological mountain of Chinese traditional belief. For the real mountain range in China, see Kunlun Mountains.

.jpg)

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

|

Institutions and temples |

|

Internal traditions Major cultural forms

Main philosophical traditions: Ritual traditions: Devotional traditions: Confucian churches and sects: |

| Chinese folk religion's portal |

Kunlun Mountain[1] (traditional Chinese: 崑崙山; simplified Chinese: 昆仑山; pinyin: Kūnlún shān), or known just as Kunlun, is an important symbol in Chinese mythology representing the axis mundi and divinity.

The mythological Kunlun Mountain should not be confused with the real, geographic Kunlun Mountains. Various locations of Kunlun Mountain are proposed in the various legends, myths, and semi-historical accounts in which it appears. These various accounts describe it as the dwelling place of various female gods and male gods, together with marvelous plants and creatures. Many important events in Chinese mythology were located on Kunlun Mountain, according to Lihui Yang, et al. (2005:160-164).

Historical development

As the mythology related to the Kunlun Mountain developed, and was influenced by the introduction of ideas about an axis mundi from the cosmology of India. Kunlun Mountain became identified with (or took on the attributes of) Mount Sumeru. (Anthony Christie 1968:74)

Another historical development in the mythology of Kunlun, (again with Indian influence) was that rather than just being the source of the Yellow River, Kunlun began to be considered to be the source of four major rivers flowing to the four quarters of the compass, according to Anthony Christie (1968:74).

The Kunlun mythos was also influenced by developments within the Taoist tradition, causing Kunlun to be perceived more as a paradise than a dangerous wilderness. (Christie, 1968:75)

Another trend argued in some recent research, is that over time, a merger of various traditions has result in a duality of paradises, an East Paradise (identified with Mount Penglai) and a West Paradise, with Kunlun Mountain identified as the West Paradise. A pole replaced a former mythic system which opposed Penglai with Guixu ("Returning Mountain"), and the Guixu mythological material was transferred to the Kunlun mythos. (Yang, et al., 2005:163).

Name

The Chinese name Kunlun 崑崙 (or 崐崘) is written with characters combining the "mountain radical" 山 with phonetics of kun 昆 and lun 侖. Alternate names for Kunlun shan include Kunling 崑陵 (with "hill") and Kunqiu 崑丘 (with "mound").

The term "Kunlun" is theoretically semantically related to the term Hundun, or, hundun (Chinese: 混沌; pinyin: hùndùn; Wade–Giles: hun-t'un; literally: "primal chaos" or "muddled confusion"), sometimes personified as a living creature: and, also semantically related is the term kongdong (Chinese: 空洞; pinyin: kōngdòng; Wade–Giles: k'ung-t'ung; literally: "grotto of vacuity"), according to Kristofer Schipper (1978: 366). Grotto-heavens were traditionally associated with mountains, as hollows or caves located in/on certain mountains. The term "Kunlun Mountain" can be translated as "Cavernous Mountain": and, the mythological Kunlun mountain has been viewed as a hollow mountain (located directly under the Pole Star), according to Schipper (1978: 365-366).

Kunlun 崑崙 was anciently used to transcribe the southern people called Gurong, who were slaves in China. Edward H. Schafer (1985:46) quotes the Old Book of Tang description. "They are also called Kurung. They are the barbarous men of the islands, great and small, of the Southern Seas. They are very black, and expose their naked Figures. They can tame and cow ferocious beasts, rhinoceroses, elephants, and the like." Schafer (1985:290) notes that besides Kunlun 崑崙, these southerners were occasionally written Gulong 古龍 or Gulun 骨論.

Julie Wilensky notes that the term kunlun (崑崙) is a "mysterious and poorly understood word first applied to dark-skinned Chinese and then expanded over time to encompass multiple meanings, all connoting dark skin." (Wilensky, 2002: 2) But then she goes on to say, "These uses of kunlun are unrelated to the name of the Kunlun Mountains." And in a footnote to this, " Chang Hsing-Iang writes that the Kunlun mountain 'region has been familiar to the Chinese from the earliest times, and no Chinese work has ever described its inhabitants as being black-skinned.'"(Wilensky, 2002: 4) She then goes on to say how "Kunlun" is used to refer to an island or islands in Southeast Asia. (Wilensky, 2002: 6-7)

Location

Various ideas of the location of the mythical Kunlun Mountain have been given: chapter eleven of the Shanhaijing describes it as being in the northwest, chapter sixteen says it is south of the western sea, and other sources place it in the center of the earth. (Yang, et al., 2005:160-164).

Some believed Kunlun to be located to the "far" west, in this case the alleged location was relocated further and further to the west, along with advances in geographical knowledge.(Christie, 1968:74) E. T. C. Werner identifies Kunlun with the Hindu Kush mountain range.(Werner, 1994[1922]:16)

At times, the mythical Kunlun Mountain has been confused with the modern Kunlun Mountains and with Kurung (or Kurung Bnam, possibly meaning "Kings of the Mountain" in Old Khmer (formerly known as Old Cambodian), and equivalent to the Sanskrit Śailarāja, also meaning "Kings of the Mountain", referring to a mythical holy cosmic mountain. Kurung (Kunlun) is known to have flourished during the time of the Tang dynasty, and seems to have developed ambassadorial relations with the Tang court, by the time of Li He (790–816), who records a visit in one of his extent poems: although geographical specifics of the state of Kunlun's location(s) remain uncertain, it is associated with trans-Gangetic India, possibly the Malay peninsula or areas controlled by the Sailendra thalassocracy (Shafer, 1985 [1963]:47-48).

Description

Kunlun Mountain has been described in various texts, as well as being depicted in art. Sometimes Kunlun appears as a pillar of the sky (or earth). Sometimes as being composed of multiple tiers. Lihui Yang, et al., (2005:160) emphasize the commonality of "mystery, grandeur, or magnificence" in the mythological descriptions. The base of the Kunlun Mountain is said to penetrate as far into the earth, as its above-ground part proceeds towards the sky (Christie, 1968:74).

Generally, accounts emphasize the difficulty of access to the mountain and even more to its more hallowed places, due to surrounding waters and steep cliffs of immense heights. Kunlun typically also has a strong association with various means to obtain immortality, or longevity. Poetic descriptions tend to lavish Kunlun with paradisaical detail: gem-like rocks and towering cliffs of jasper and jade, exotic jeweled plants, bizarrely formed and colored magical fungi, and numerous birds and other animals, together with humans who have become immortal beings. Sometimes it is the Eight Immortals who are seen, coming to pay their respects to the goddess Xiwangmu, perhaps invited to join her in a feast of immortal repast. Such anyway, was the well-worn image, which was also a motif frequently painted, carved, or otherwise depicted in the material arts.

Association with divinity

Supreme Deity

Kunlun is believed to be the representation of the Supreme Deity (Taidi). According to some sources, his throne is at the top tier of the mountain and known as the "Palace of Heaven". As Kunlun was sometimes viewed as the pillar holding up the sky and keeping it separated from the earth, some accounts place the top of Kunlun in Heaven rather than locating it as part of the earth: in this case the Supreme Deity's abode on Kunlun is actually in Heaven, and Kunlun functions as a sort of ladder which could be used to travel between earth and Heaven. Accordingly, any person who succeeded in climbing up to the top of Kunlun would magically become an immortal spirit. (Yang, 2005: 160-162).

Xiwangmu

Although not originally located on Kunlun, but rather on a Jade Mountain neighboring to the north (and west of the Moving Sands), Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West, in later accounts was relocated to a palace protected by golden ramparts, within which immortals (xian) feasted on bear paws, monkey lips, and the livers of dragons, served at the edge of the Lake of Gems. Every 6000 years the peaches which conferred immortality upon those who ate them would be served (except the time when they were purloined by Monkey King). Originally a plague deity with tiger teeth and leopard tail, she became a beautiful and well-mannered goddess responsible for guarding the herb of immortality (Christie, 1968:78-79).

Yu Shi

Yu Shi, a Chinese spirit or god of rain, also known as the "Lord of Rain" or "Leader of Rain" is thought to have his dwelling place upon the Kunlun slopes. During the reign of Shennong, a certain Chisongzi (Master Red Pine) performed a rain-making ceremony which successfully ended a terrible drought, leading to his promotion to "Yu Shi", "Master of Rain" (Christie, 1968:75).

Shamans

According to the Shanhaijing, the top of Kunlun is the habitation of shamans, depicting Wu Peng holding the herb of immortality there, in the company of five other shamans. (Hawkes, 2011[1985]: 45)

Xian

In later tradition Kunlun was pictured as a Daoist paradise, inhabited by xian, or Daoist immortals (humans who had metamorphosed into superhuman form), which was presided over by Xiwangmu. The xian were often seen as temporary residents, who visited by means of flying on the back of a magical crane or dragon.

Creatures

Kunlun has a lively bestiary, with various more-or-less fantastic beasts and birds described as present in its environs. Often the tiger or beings with tiger-like features are associated with Kunlun, since the tiger is symbolic of the west, as Kunlun is often associated with the Western Paradise (Christie, 1968:34). Creatures symbolic of immortality are often seen or described in depictions of Kunlun, such as deer or cranes. Xiwangmu is often identified as having a pet spotted deer. Besides the cranes (traditionally thought of as the mounts or the transformations of immortals), other birds come and go from the mountain, flying errands for Xiwangmu: these blue (or green) birds are her qingniao. Sometimes the poets claim to have received a happy inspiration during a visit by one of these birds, carrying a message from Xiwangmu.

Plants

The flora of Kunlun and its environs is in keeping with the rest of its natural (and supernatural qualities), and includes the Pearl and Jade Trees, the Tree of Immortality, and Tree Grain, the last of which (Muhe) was forty feet and height and five spans in thickness (Yang, et al., 2005:160). Peaches are (and have been) often associated with Xiwangmu (Eberhard, 2003: 320) The langgan (traditional Chinese: 琅 (variantly 瑯玕; simplified Chinese: 琅玕; pinyin: lánggān; Wade–Giles: lang-kan) was a tree of fairy gems in colours of blue or green, which was reported to grow on Kunlun in the classic books of the Zhou and early Han dynasties. (Schafer, 1963: 246)

Places

Kunlun is described as having various structures, areas, or significant features either on or around the area of the mountain. The palace of Xiwangmu, sometimes described as having golden ramparts, was located on Kunlun: those blessed to gather there might partake of the fruit of longevity (Christie, 1968:72). Often her palace is described as having a park or garden, bordering a Jasper Pool. Of gardens, a (the) Hanging Garden was referenced early on.

Events

Kunlun Mountain is a major scene of action in various myths, as well as literary works derived from the myths, legends, or religious descriptions or depictions.

Marriage of Nüwa and Fuxi

Fuxi and Nuwa's marriage took place on the mountain of Kunlun. Generally held to be brother and sister, and the last surviving human beings after a catastrophic flood, the incest taboo was waived by an explicit sign after prayerful questioning of a divine being who approved their marriage and thus the repopulation of the world.

Mu, Son of Heaven

Mu son of Heaven is one visitor, carried along on his trip by eight extraordinary mounts, depicted in art as "weird and unworldly" (Shafer, 1985 [1963]:59).

Literary allusions

Many important literary allusions to Kunlun Mountain exist, including famous novels, poems, and theatrical pieces.

Novels

Among other literature, Kunlun Mountain appears in Fengshen Yanyi, Legend of the White Snake, the Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven, Kunlun Nu, Journey to the West (also known as Monkey), and the manga 3×3 Eyes.

Theater

The Kunlun Slave (slave from Kunlun) was a stock character in Chinese theater, and known in Japanese theater "Konron". He was portrayed as exotic in appearance, and possessed of superhuman powers. Mei Dingzuo (1549-1615) wrote a play "How the Kunlun Slave Became an Immortal".

Poetry

Kunlun Mountain is a subject of poetic allusion from the ancient poems "Li Sao" and "Heavenly Questions" by Qu Yuan, through frequent mentions in the medieval Tang dynasty poetry, and, in the twentieth century in Mao Zedong's 1935 poem "Kunlun".

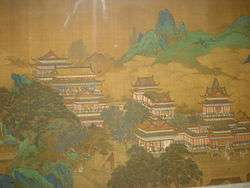

Gallery

-

Peach Festival of the Queen Mother of the West, a Chinese Ming Dynasty painting from the early 17th century, by an anonymous artist. A mythological event traditionally occurring on the mythological Kunlun Mountain. From the Freer and Sackler Galleries of Washington D.C.

-

A Japanese painting depicting Emperor Wudi of the Han dynasty meeting Xiwangmu, according to a fictional account of his magical transportation to Kunlun Mountain.

-

A throne and screen from the imperial workshops in the beginning of the era of the Kangxi Emperor (1662-1722). The screen depicts the Western Paradise, mythologically located on Kunlun Mountain, with scenes of mountains, valleys, seas, terraces, lakes, and palaces. Shown is the arrival of its ruler, the Queen Mother of the West (Xiwangmu), shown riding a phoenix, and the Eight Immortals awaiting her arrival.

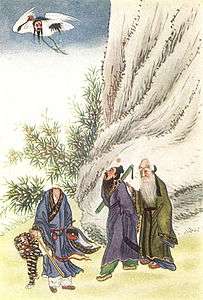

-

"Chiang Tzŭ-ya at K’un-lun"

See also

- Axis mundi

- Chi (mythology), has some discussion related to Kunlun beastiary

- Chinese mythology, a general article on Chinese mythology

- Feather Mountain, mythological location of Gun's demise

- Four Mountains, advisors to emperors Yao and Shun, sometimes associated with four cardinal mountains

- Gigaku, article mentioning the character from Kunlun

- Hundun, mentions kunlun in etymological terms, with cognate meaning

- Jade Mountain (mythology), another mythical mountain

- Mount Buzhou, another mythical mountain

- Mount Penglai, another mythical mountain

- Neijing Tu, Daoist internal alchemy diagram relating human anatomy and cosmic theory

- Peaches of Immortality, magical fruit providing longevity

- Sungmo, Korean primordial goddess associated to a "western mountain"

- Xiwangmu, Chinese primordial goddess identified with Kunlun

Notes

- ↑ The Chinese language does not necessarily distinguish between singular and plural, thus from a purely grammatical viewpoint "Kunlun Mountain" is an equally valid translation as "Kunlun Mountains", also 山 (shān) can mean "mountain", "hill", or "mound"; however, most descriptions and many depictions focus on a more singular and spectacular manifestation, thus the translation "Kunlun Mountain" seems appropriate. Anthony Christie uses "Mount", but "Mountain" is probably less ambiguous

References

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (2003 [1986]), A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00228-1

- Hawkes, David, translator and introduction (2011 [1985]). Qu Yuan et al., The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Schipper, Kristofer (Feb. - May, 1978). "The Taoist Body", in History of Religions , Vol. 17, No. 3/4, Current Perspectives in the Study of Chinese Religions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. < Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062436 (subscription required) >

- Werner, E. T. C. (1994 [1922]). Myths and Legends of China. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28092-6

- Wilensky, Julie (July, 2002). "The Magical Kunlun and 'Devil Slaves:' Chinese Perceptions of Dark-skinned People and Africa before 1500", in Sino-Platonic Papers 122. New Haven:Yale. < Stable URL: http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp122_chinese_africa.pdf >

- Yang, Lihui, et al. (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6