Battle of Kwajalein

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Kwajalein was fought as part of the Pacific campaign of World War II. It took place from 31 January-3 February 1944, on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Employing the hard-learned lessons of the battle of Tarawa, the United States launched a successful twin assault on the main islands of Kwajalein in the south and Roi-Namur in the north. The Japanese defenders put up stiff resistance, although outnumbered and under-prepared. The determined defense of Roi-Namur left only 51 survivors of an original garrison of 3,500.

For the US, the battle represented both the next step in its island-hopping march to Japan and a significant moral victory because it was the first time the Americans had penetrated the "outer ring" of the Japanese Pacific sphere. For the Japanese, the battle represented the failure of the beach-line defense. Japanese defenses became prepared in depth, and the battles of Peleliu, Guam, and the Marianas proved far more costly to the US.

Background

Geography

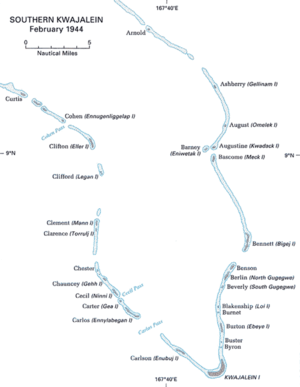

Kwajalein Atoll is in the heart of the Marshall Islands. It lies in the Ralik Chain, 2,100 nmi (2,400 mi; 3,900 km) southwest of Honolulu, Hawaii at 8°43′N 167°44′E / 8.717°N 167.733°E. Kwajalein is the world's largest coral atoll and comprises 93 islands and islets, it has a land area of 1,560 acres (6.33 km²),[1]:12 and surrounds one of the largest lagoons in the world, measuring 324 mi² (839 km²) in size.

The two most significant land masses are Kwajalein Island in the south, and the linked islands of Roi-Namur in the north. By the start of World War II, the Marshalls (South Pacific Mandate) were already an integral part of the Japanese perimeter of defense. Its facilities were being utilized as outlying bases for submarines and surface warships, as well as for air staging for future advances being planned against Ellice, the Fiji Islands, and Samoa.

Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign

After the capture of Makin and Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, the next step in the United States Navy's campaign in the central Pacific was the Marshall Island chain.[1]:7 These islands had been Imperial German colonies, after their purchase from Spain in 1899,.[1]:11 At the end of World War I, however, they were assigned to Japan in the post-war settlement as the "Eastern Mandates". The islands then became a mystery because the Japanese closed them to the outside world. It was presumed the Japanese had built illegal fortifications throughout the islands, but the precise extent of such fortifications was unknown.[1]:9 Japan regarded them as part of the "outer ring" of their territory.[1]:10

The strategic importance of the Marshalls had been recognized as early as 1921 in Plan Orange, an American interwar plan for a possible conflict with Japan. The Marshalls were a key step in the island-hopping march to the Japanese mainland.[1]:7

After losing the Solomon Islands and New Guinea to the Allies in 1943, the Japanese command decided that the Gilbert and Marshall Islands were expendable.[1]:21 They preferred fighting a decisive battle closer to home. Nevertheless, the Marshalls were reinforced at the end of 1943 to make their capture more costly for the Americans. By January 1944, the regional commander in Truk, Admiral Masashi Kobayashi, had 28,000 troops to defend the Marshalls, although he had very few aircraft.[1]:33

Japanese planning and preparations

The 6th Base Force, under the command of Rear Admiral Monzo Akiyama, and headquartered on Kwajalein since August 1941, was the principal defense force of the islands.[1]:31 Akiyama, however, had his men spread out over a very wide area, with IJN air bases located on Roi-Namur, Mille, Maloelap, Eniwetok, and Wotje.[1]:31 Garrison troops on the island included the 1st Company, 3rd Mobile Battalion, 1st Amphibious Brigade, plus units of the 2nd Mobile Battalion.[1]:31

The defense system on the islands was mostly in line, with little or no depth.[1]:33 The Japanese had twin 12.7 cm guns on each end of the island plus 80mm guns on the ocean and lagoon sides.[1]:35 The 22nd Air Flotilla, depleted after the Gilbert campaign, had 128 aircraft in the Marshalls, 10 on Kwajalein.[1]:31

US planning and preparation

The Marshall campaign planned by the US, involved attacks on seven islands, bypassing many more.[1]:18 Operation Flintlock had nine phases, the main phase being the capture of Kwajalein and Majuro Atolls, a second phase, Operation Catchpole, being the capture of Eniwetok, and remaining phases being the capture of remaining islands.[1]:18 Bombardment by the Seventh Air Force, and a carrier air attack on 4 Dec. 1943, followed by additional attacks in Jan. 1944, destroyed all Japanese aircraft.[1]:36,18 The 4th Marine Division—under Major General Harry Schmidt—was assigned to Roi-Namur, and the Army's 7th Infantry Division—under Major General Charles H. Corlett—would make the assault on Kwajalein.[1]:18

Staging through Baker Island airfield, B-24 Liberators bombed strategic targets. In the beginning, the most important was Mili Atoll, the Japanese base closest to the Gilberts and Maloelap, the most powerful enemy bases threatening the upcoming operations. Mille was the subject of several attacks throughout November, causing considerable damage to installations and high losses of aircraft for the Japanese. But Mille remained the only base within fighter reach of the Gilberts, and the defenders managed to keep the facilities there operational and reinforced with aircraft. Following the capture of Tarawa and until 19 December, 106 B-24s dropped a total of 122 short tons (111 t) of explosives on Mille's airbase. The largest of those raids came on 4 December when 34 B-24s pulverized the atoll in conjunction with carrier-based bombing raids of other parts of the Marshalls. On 18 December, renewed strikes were initiated against enemy targets on Mille with land-based Douglas A-24 Banshee dive bombers and Bell P-39 Airacobra fighters making their debut in the Marshall air offensive. Japanese losses for the day amounted to 10 fighters (four on the ground) and four damaged. Other aircraft types participating in the offensive included B-25 Mitchells and Curtiss P-40 Warhawks.

It was necessary to take another atoll in the eastern Marshalls—Majuro. This feature is 220 mi (190 nmi; 350 km) southeast of Kwajalein and could serve as an advanced air and naval base as well as safeguard supply lines to Kwajalein. Majuro was very lightly defended and only the V Amphibious Corps Marine Reconnaissance Company and the 2nd Battalion, 106th Infantry, 7th Infantry Division were employed in its capture. The island was taken on 31 January 1944, without any US casualties.[1]:37–38

Battle

The U.S. forces for the landings were Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner's 5th Fleet Amphibious Force, and Major General Holland M. Smith's V Amphibious Corps, which comprised the 4th Marine Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, the Army's 7th Infantry Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett, as well as the 22nd Marines, and the Army's 106th and 111th Infantry regiments. The 4th and 7th Divisions were assigned to the initial landings at Kwajalein, while the 2nd Battalion of the 106th was assigned to the simultaneous capture of Majuro Atoll. The rest of the 106th and the 22nd Marines were in reserve for Kwajalein, while awaiting the following assault on Eniwetok, scheduled for three months later.

The 7th Infantry Division began by capturing the small islands labeled Carlos, Carter, Cecil, and Carlson on 31 January, which were used as artillery bases for the next day's assault.[1]:54–67 Kwajalein Island is 2.5 mi (4.0 km) long, but it is only 880 yd (800 m) wide. There was therefore no possibility of defence in depth, and the Japanese planned to counter-attack the landing beaches.[1]:33 They had not realized until the battle of Tarawa that American amphibious vehicles could cross coral reefs and land on the lagoon side of an atoll; accordingly the strongest defences on Kwajalein faced the ocean.[1]:33 The bombardment by the Southern Attack Force, including the battleship USS Tennessee,[1]:44,54 plus B-24 bombers from Apamama and artillery on Carlson island was devastating. The Official U.S. Army history of the battle quotes a soldier as saying "the entire island looked as if it had been picked up 20,000 feet and then dropped." Landing beaches Red 1 and 2 were assaulted at 0930 on 1 February, the Americans reaching halfway across the runway by sunset.[1]:56–60 Although the Japanese counterattacked every night, the island was declared secure by the end of the fourth day.[1]:66

On the north side of the atoll, the 4th Marine Division followed a similar plan, first capturing islets Ivan, Jacob, Albert, Allen, and Abraham on 31 January, and then landing on Roi-Namur on 1 February.[1]:38–54 The airfield on the western half (Roi) was captured quickly, and the eastern half (Namur) fell the next day. The worst setback came when a Marine demolition team threw a satchel charge of high explosives into a Japanese bunker, not realizing it was a torpedo warhead magazine. The resulting explosion killed twenty Marines and wounded dozens more[2] and caused an observation pilot to radio, "The whole damn island has blown up!"[3]

Aftermath

The relatively easy capture of Kwajalein demonstrated US amphibious capabilities and showed that the changes to training and tactics after the costly battle of Tarawa had been effective.[1]:89 It allowed Nimitz to speed up operations in the Marshalls and invade Ebeye Island on 3–4 February, Engebi Island on 18–19 February, Eniwetok Island on 19–21 February, and Parry Island on 22–23 February 1944.[1]:66–85

The Japanese also realized that beach-line defenses were too vulnerable to naval and aerial bombardment. In the campaign for the Mariana Islands, the defense in depth on Guam and Peleliu would be much harder to overcome than the comparatively thin line on Kwajalein.

After the war ended, working US airplanes were sunk off the Atoll, as a cheaper method than sending the airplanes back to the US. The airplane graveyard included several Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, Vought F4U Corsairs, Grumman TBF Avengers, Curtiss SB2C Helldivers, North American B-25 Mitchells, Curtiss C-46 Commandos and Grumman F4F Wildcats.[4]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Rottman, G., 2004, The Marshall Islands 1944: "Operation Flintlock, the capture of Kwajalein and Eniwetok", Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, ISBN 1-84176-851-0

- ↑ Duncan, Basil. "Roi-Namur". THE MARSHALL ISLANDS CAMPAIGN. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Spector, Ronald (1985), EAGLE AGAINST THE SUN: The American War With Japan (New York: Random House), p. 270

- ↑ "GALLERY: WWII Airplane Graveyard in Pacific Ocean". Retrieved 2015-07-23.

References

- Bailey, Dan E. (1992). World War II: Wrecks of the Kwajalein and Truk Lagoons. North Valley Diver Publications. ISBN 0-911615-05-9.

- Marshall, S. L. A.; Joseph G. Dawson (2001). Island Victory: The Battle of Kwajalein Atoll. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8272-9.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1961). Aleutians, Gilberts and Marshalls, June 1942 – April 1944, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ASIN B0007FBB8I.

- Rottman, Gordon; Howard Gerrard (2004). The Marshall Islands 1944: "Operation Flintlock, the capture of Kwajalein and Eniwetok". Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-851-0.

- Sauer, Howard (1999). "Kwajalein". The Last Big-Gun Naval Battle: The Battle of Surigao Strait. Palo Alto, California: The Glencannon Press. ISBN 1-889901-08-3.- Firsthand account of the U.S. pre-invasion bombardment operation by a crewmember of the USS Maryland.

Further reading

- Wright III, Burton. Eastern Mandates. US Army Campaigns in World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-23.

- Chapin, Captain John C., USMCR (Ret), Breaking the Outer Ring: Marine Landings in the Marshall Islands, Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps, 1994.

- Heinl, Robert D., and John A. Crown (1954). "The Marshalls: Increasing the Tempo". USMC Historical Monograph. Historical Division, Division of Public Information, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- Dyer, George Carroll (1956). "The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner". United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

External links

- What Makes a Battle — Moving images from Kwajalein island during battle

- Soldiers of the 184th Infantry, 7th ID in the Pacific, 1943–1945

- Animated History of The Battle for Kwajalein

Coordinates: 8°43′N 167°44′E / 8.717°N 167.733°E