Languages of China

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of China |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

|

Monuments |

|

Organisations

|

|

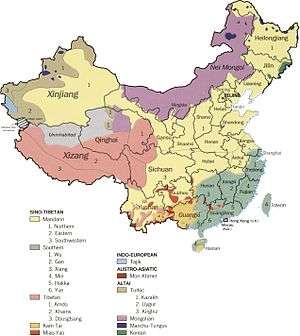

The languages of China are the languages that are spoken by China's 56 recognized ethnic groups. The predominant language in China, which is divided into seven major dialect groups, is known as Hanyu (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語; pinyin: Hànyǔ). and its study is considered a distinct academic discipline in China.[4] Hanyu, or Han language, spans eight primary dialect groups, that differ from each other morphologically and phonetically to such a degree that dialects from different regions can often be mutually unintelligible. The languages most studied and supported by the state include Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang. China has 297 living languages according to Ethnologue.[5]

Standard Chinese (known in China as Putonghua), a form of Mandarin Chinese, is the official national spoken language for the mainland and serves as a lingua franca within the Mandarin-speaking regions (and, to a lesser extent, across the other regions of mainland China). Several other autonomous regions have additional official languages. For example, Tibetan has official status within the Tibet Autonomous Region, and Mongolian has official status within Inner Mongolia. Language laws of China do not apply to either Hong Kong or Macau, which have different official languages (Cantonese, English and Portuguese) than the mainland.

Spoken languages

The spoken languages of nationalities that are a part of the People's Republic of China belong to at least nine families:

- The Sino-Tibetan family: 19 official ethnicities (including the Han and Tibetans)

- The Tai–Kadai family: several languages spoken by the Zhuang, the Bouyei, the Dai, the Dong, and the Hlai (Li people). 9 official ethnicities.

- The Hmong–Mien family: 3 official ethnicities

- The Austroasiatic family: 4 official ethnicities (the De'ang, Blang, Gin (Vietnamese), and Wa)

- The Turkic family: Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Salars, etc. 7 official ethnicities.[6]

- The Mongolic family: Mongols, Dongxiang, and related groups. 6 official ethnicities.[6]

- The Tungusic family: Manchus (formerly), Hezhe, etc. 5 official ethnicities.

- The Korean language

- The Indo-European family: 2 official ethnicities (the Russians and Tajiks (actually Pamiri people). There is also a heavily Persian-influenced Äynu language spoken by the Äynu people in southwestern Xinjiang who are officially considered Uyghurs.

- The Austronesian family: 1 official ethnicity (the Gaoshan, who speak many languages of the Formosan branch), 1 unofficial (the Utsuls, who speak the Tsat language but are considered Hui.)

Below are lists of ethnic groups in China by linguistic classification. Ethnicities not on the official PRC list of 56 ethnic groups are italicized. Respective Pinyin transliterations and simplified Chinese characters are also given.

Sino-Tibetan

- Sinitic

- Chinese/Han, Hàn, 汉; Traditional Chinese: 漢

- Chinese Muslim/Hui, Huí, 回

- Chinese/Han, Hàn, 汉; Traditional Chinese: 漢

- Tibeto-Burman

- Bai, Bái, 白

- Tujia, Tǔjiā, 土家

- Qiangic

- Qiang, Qiāng, 羌

- Pumi/Prinmi, Pǔmǐ, 普米

- Baima, Báimǎ, 白马 ; Traditional Chinese: 白馬

- Tangut, Xīxià, 西夏 (extinct)

- Bodish

- Tibetan, Zàng, 藏

- Lhoba, Luòbā, 珞巴

- Monpa/Monba, Ménbā, 门巴; Traditional Chinese: 門巴

- Lolo–Burmese–Naxi

- Jingpho–Nungish–Luish

- Jingpho, Jǐngpō, 景颇 ; Traditional Chinese: 景頗

- Derung, Dúlóng, 独龙 ; Traditional Chinese: 獨龍

- Nu, Nù, 怒

Tai–Kadai

(Possibly the ancient Bǎiyuè 百越)

- Kra

- Gelao, Gēlǎo, 仡佬

- Kam–Sui

- Hlai/Li, Lí, 黎

- Tai

- Zhuang (Vahcuengh), Zhuàng, 壮 ; Traditional Chinese:壯

- Northern Zhuang, Běibù Zhuàngyǔ, 北部壮语 ; Traditional Chinese:北部壯語

- Southern Zhuang, Nánbù Zhuàngyǔ, 南部壮语 ; Traditional Chinese:南部壯語

- Bouyei, Bùyī, 布依

- Dai, Dǎi, 傣

- Tai Lü language, Dǎilèyǔ, 傣仂语 ; Traditional Chinese: 傣仂語

- Tai Nüa language, Déhóng Dǎiyǔ, 德宏傣语 ; Traditional Chinese: 德宏傣語

- Tai Dam language, Dǎinǎyǔ, 傣哪语; Dǎidānyǔ, 傣担语

- Tai Ya language, Dǎiyǎyǔ, 傣雅语

- Tai Hongjin language, Hónghé Dǎiyǔ, 红金傣语 ; Traditional Chinese: 紅金傣語

- Zhuang (Vahcuengh), Zhuàng, 壮 ; Traditional Chinese:壯

Turkic

- Karluk

- Uyghur, Wéiwúěr, 维吾尔; Traditional Chinese: 維吾爾

- Äynu, Àinǔ, 艾努

- Uzbek, Wūzībiékè, 乌孜别克 ; Traditional Chinese: 烏茲別克

- Kipchak

- Kazakh, Hāsàkè, 哈萨克 ; Traditional Chinese: 哈薩克

- Kyrgyz, Kēěrkèzī, 柯尔克孜; Traditional Chinese: 柯爾克孜

- Tatar, Tǎtǎěr, 塔塔尔 ; Traditional Chinese:塔塔爾

- Oghuz

- Salar, Sǎlá, 撒拉

- Siberian

- Old Turkic, Tūjué, 突厥 (extinct)

- Western Yugur, Yùgù, 裕固

- Old Uyghur, Huíhú, 回鶻 (extinct)

- Fuyu Kyrgyz, Fúyú Jí'ěrjísī, 扶餘吉爾吉斯

- Tuvan, túwǎ, 圖瓦

Mongolic

- Mongolian, Měnggǔ, 蒙古

- Oirat, wèilātè, 衛拉特

- Torgut Oirat, tǔěrhùtè, 土爾扈特

- Buryat, bùlǐyàtè, 布里亞特

- Daur, Dáwò'ěr, 达斡尔

- Khitan, Qìdān, 契丹 (extinct)

- Southeastern

- Monguor, Tǔ [Zú], 土[族]

- Eastern Yugur, Yùgù, 裕固

- Dongxiang, Dōngxiāng, 东乡 ; Traditional Chinese: 東鄉

- Bonan, Bǎoān, 保安

- Kangjia, Kāngjiā, 康家语 ; Traditional Chinese: 康加語

- Monguor, Tǔ [Zú], 土[族]

Tungusic

- Southern

- Manchu, Mǎnzhōu/Mǎn, 满洲/满 ; Traditional Chinese: 滿洲/滿

- Jurchen, Nǚzhēn, 女真 (extinct)

- Xibe, Xībó, 锡伯 ; Traditional Chinese: 錫伯

- Nanai/Hezhen, Hèzhé, 赫哲

- Manchu, Mǎnzhōu/Mǎn, 满洲/满 ; Traditional Chinese: 滿洲/滿

- Northern

- Evenki, Èwēnkè, 鄂温克

- Oroqen, Èlúnchūn, 鄂伦春 ; Traditional Chinese: 鄂倫春

Korean/Choson

Cháoxiǎn, 朝鲜 ; Traditional Chinese: 朝鮮

Hmong–Mien

(Possibly the ancient Nánmán 南蛮 ; Traditional Chinese: 南蠻)

- Hmong/Miao, Miáo, 苗

- Mien/Yao, Yáo, 瑶 ; Traditional Chinese: 瑤

- She, Shē, 畲

Austroasiatic

- Palaung-Wa

- Vietnamese/Kinh, Jīng, 京

Austronesian

- Formosan languages, Gāoshān, 高山

- Tsat, Huíhuī 回輝

Indo-European

- Russian, Éluósī, 俄罗斯 ; Traditional Chinese: 俄羅斯

- Tocharian, tǔhuǒluó, 吐火羅 (extinct)

- Saka, sāi, 塞 (extinct)

- Pamiri, (mislabelled as "Tajik", Tǎjíkè, 塔吉克)

- Portuguese (spoken in Macau)

- English (spoken in Hong Kong and in Weihai)

- German (spoken in Qingdao)

- French (spoken in Zhanjiang)

Mixed

Written languages

The following languages traditionally had written forms that do not involve Chinese characters (hanzi):

- The Dai – Tai Lü language or Tai Nüa language - Tai Lü alphabet or Tai Nüa alphabet

- The Kazakhs – Kazakh language – Kazakh Arabic alphabet

- The Koreans – Korean language – Chosŏn'gŭl alphabet

- The Kyrgyz – Kyrgyz language – Kyrgyz Arabic alphabet

- The Manchus – Manchu language – Manchu alphabet

- The Mongolians – Mongolian language – Mongolian alphabet

- The Naxi – Naxi language - Dongba characters

- The Sui – Sui language – Sui script

- The Tibetans – Tibetan language – Tibetan alphabet

- The Uyghurs – Uyghur language – Uyghur Arabic alphabet

- The Xibe – Xibe language – Manchu alphabet

- The Yi – Yi language – Yi syllabary

Many modern forms of spoken Chinese languages have their own distinct writing system using Chinese characters that contain colloquial variants. These typically are used as sound characters to help determine the pronunciation of the sentence within that language:

- Written Cantonese

- Chữ nôm - Vietnamese

- Written Hokkien

- Shanghainese

Some formerly have used Chinese characters

- The Jurchens (Manchu ancestors) – Jurchen language – Jurchen script

- The Koreans – Korean language – Hanja

- The Khitans (Mongolic people) – Khitan language – Khitan script

- The Tanguts (Sino-Tibetan people) – Tangut language – Tangut script

- The Zhuang (Tai people) – Zhuang languages – Sawndip

During Qing dynasty, palaces, temples, and coins have sometimes been inscribed in four scripts:

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty, the official writing system was:

Chinese banknotes contain several scripts in addition to Chinese script. These are:

Other writing system for Chinese languages in China include:

Ten nationalities who never had a written system have, under the PRC's encouragement, developed phonetic alphabets. According to a government white paper published in early 2005, "by the end of 2003, 22 ethnic minorities in China used 28 written languages."

Language policy

The Chinese language policy in mainland China is heavily influenced by the Soviet nationalities policy and officially encourages the development of standard spoken and written languages for each of the nationalities of China. However, in this schema, Han Chinese are considered a single nationality and the official policy of the People's Republic of China (PRC) treats the different varieties of Chinese differently from the different national languages, even though their differences are as significant as those between the various Romance languages of Europe. While official policies in mainland China encourage the development and use of different orthographies for the national languages and their use in educational and academic settings, realistically speaking it would seem that, as elsewhere in the world, the outlook for minority languages perceived as inferior is grim.[7] The Tibetan Government-in-Exile argue that social pressures and political efforts result in a policy of sinicization and feels that Beijing should promote the Tibetan language more. Because many languages exist in China, they also have problems regarding diglossia. Recently, in terms of Fishman's typology of the relationships between bilingualism and diglossia and his taxonomy of diglossia (Fishman 1978, 1980) in China: more and more minority communities have been evolving from "diglossia without bilingualism" to "bilingualism without diglossia." This could be an implication of mainland China's power expanding.[8]

Study of foreign languages

It is also considered increasingly prestigious and useful to have some ability in English, which is a required subject for persons attending university. During the 1950s and 1960s, Russian had some social status among elites in mainland China as the international language of socialism. Japanese is the second most-studied foreign language in China.

In the late 1960s, English replaced the position of Russian to become the most important foreign language in China. After the Reform and Opening-up policy in 1988, English is taught in the public schools starting in the third year of primary school,[2][3] languages other than English are now considered to be "minor languages" (小语种 ; Traditional Chinese:小語種 xiǎo yǔzhǒng) and are only really studied at the university level apart from some special schools which are called Foreign Language Schools in some well-developed cities. Japanese and Korean are not considered as "minor languages" by most of the Chinese people. Russian, French, and German are widely taught in Universities and colleges nowadays.

In Northeast China, there are many bilingual schools (Mandarin-Japanese; Mandarin-Korean; Mandarin-Russian), in these schools, students learn other languages other than English.

The Economist, issue April 12, 2006, reported that up to one fifth of the population is learning English. Gordon Brown, the former British Prime Minister, estimated that the total English-speaking population in China will outnumber the native speakers in the rest of the world in two decades.[9]

Literary Arabic is studied by Hui students.[10]

Literary Arabic education was promoted in Islamic schools by the Kuomintang when it ruled mainland China.[11]

Portuguese is taught in Macau as one of the official languages there and as a center of learning of the language in the region, although use has declined drastically since its transfer from Portugal to the PRC.

Further reading

- Kane, D. (2006). The Chinese language: its history and current usage. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle. ISBN 0-8048-3853-4

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Webster, J. (2005). Studies in Chinese language. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-5874-2

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China (illustrated, reprint ed.). N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069101468X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Hong, B. (1978). Chinese language use. Canberra: Contemporary China Centre, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 0-909596-29-8

- Cheng, C. C., & Lehmann, W. P. (1975). Language & linguistics in the People's Republic of China. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-74615-6

See also

- Chinglish

- Demographics of the People's Republic of China

- Demographics of Taiwan

- Hong Kong English

- Languages of Hong Kong

- Languages of Macau

- Languages of Taiwan

- Macanese Portuguese

- Nationalities of China

- Classification schemes for Southeast Asian languages

References

This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Burma past and present, by Albert Fytche, a publication from 1878 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Burma past and present, by Albert Fytche, a publication from 1878 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ↑ http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/michaellaw/2014/02/19/cantonese-in-hong-kong-not-the-official-language

- 1 2 http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/english-craze-hits-chinese-language-standards

- 1 2 http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/asians-offer-region-lesson-%E2%80%93-english

- ↑ Dwyer, Arienne (2005). The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur Identity, Language Policy, and Political Discourse (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1-932728-29-5.

Tertiary institutions with instruction in the languages and literatures of the regional minorities (e.g., Xinjiang University) have faculties entitled Hanyu xi ("Languages of China Department") and Hanyu wenxue xi ("Literatures of the Languages of China Department").

- ↑ Languages of China – from Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.

- 1 2 Western Yugur is a Turkic language, whereas is Eastern Yugur a Mongolic language.

- ↑ The prospects for the long-term survival of Non-Han minority languages in the south of China

- ↑ Minglang Zhou, Multilingualism in China the politics of Writing reforms for minority languages 1949-2002 (2003)

- ↑ "English beginning to be spoken here". The Economist. 2006-04-12.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999), China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects, Richmond: Curzon Press, p. 155, ISBN 0-7007-1026-4, retrieved 2010-06-28

- ↑ Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.