Lavras

| Lavras | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

|

Partial view of the central region | |||

| |||

| Etymology: Mining and tillage | |||

| Nickname(s): Cidade dos Ipês e das Escolas ("City of the Ipês and Schools") | |||

| Anthem: Hino do município de Lavras | |||

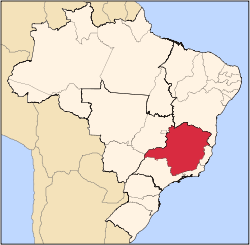

Location of Lavras | |||

| Coordinates: 21°14′42″S 45°00′00″W / 21.24500°S 45.00000°WCoordinates: 21°14′42″S 45°00′00″W / 21.24500°S 45.00000°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Region | Southeast | ||

| State |

| ||

| Mesoregion | Campo das Vertentes | ||

| Founded | 1729 | ||

| Town rights | 1831 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Silas Costa Pereira (PMDB) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 564.495 km2 (217.953 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 919 m (3,015 ft) | ||

| Population (2016)[1] | |||

| • Total | 101,208 | ||

| • Density | 179,29/km2 (46,440/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Lavrense | ||

| Time zone | BRT (UTC−3) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | BRST (UTC−2) | ||

| Postal Code | 37200-000 | ||

| Area code(s) | (+55) 35 | ||

| Website | www.lavras.mg.gov.br | ||

Lavras is a municipality in Southern Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Located at an altitude of 919 m, it has a population of 101,208 inhabitants (2016).[1] The area of the municipality is 564.495 km². The average annual temperature is 19.6°C and the average annual rainfall is 1,511 millimetres.

Located at the Green Valley and Waterfalls tourist circuit, it is also near Waters circuit — a series of spas in the state of São Paulo and Minas Gerais — and the Inconfidentes Trail circuit — a historical region of Minas. Lavras is connected by highway to the state capital, Belo Horizonte (237 km), to São Paulo (379 km) and Rio de Janeiro (423 km).[2]

History

| Population growth | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1760 | 1,000 | — |

| 1813 | 10,612 | +4.56% |

| 1834 | 11,322 | +0.31% |

| 1854 | 14,203 | +1.14% |

| 1872 | 31,813 | +4.58% |

| 1890 | 24,756 | −1.38% |

| 1900 | 38,685 | +4.56% |

| 1920 | 42,859 | +0.51% |

| 1940 | 42,187 | −0.08% |

| 1950 | 27,364 | −4.24% |

| 1960 | 37,262 | +3.14% |

| 1970 | 44,449 | +1.78% |

| 1980 | 52,710 | +1.72% |

| 1991 | 65,893 | +2.05% |

| 2000 | 78,772 | +2.00% |

| 2010 | 92,171 | +1.58% |

| 2016 | 101,208 | +1.57% |

Early settlement

The settlement of the Campos de Sant'Ana das Lavras do Funil dated from the first half of the 18th century, founded in 1729.[3] The first inhabitants were the Paulista family of Francisco Bueno da Fonseca (c. 1670-1752), leader of a revolt against a Portuguese judge in São Paulo in 1712.[4] Bueno da Fonseca, his sons and other explorers, settled in the region of the rivers Capivari and Grande by the years of 1720[5] or 1721,[6] where they were engaged in the search for gold and in the opening of new roads to the Goiás mines. In 1737 the explorers receive from the Governor Martinho de Mendonça an allotment letter confirming their region occupation, which grew through agriculture and livestock.

On June 18, 1759, Bartolomeu Bueno do Prado, Anhangüera's grandson and Francisco Bueno da Fonseca's son-in-law, left the village heading 400 men, summoned from the entire Minas Gerais captaincy, to disrupt the quilombo confederation of Campo Grande. The influence of captain Bueno da Fonseca's family contributed to the village's rapid growing. In 1760 they managed to change the parish seat from Carrancas, as Lavras do Funil already had 1,000 inhabitants, twice more than the former.[7] In 1813 the village was elevated to freguesia, detaching itself from Carrancas. That time, Lavras had 6 chapels and a population of 10,612 souls.

19th century

On the Imperial period, Lavras obtained its political and administrative emancipation, becoming a municipality in 1831 and city in 1868, when there was a change in municipal toponymic from "Lavras do Funil" to "Lavras".[8] In 1832 the inspector Manuel Custódio Neto reported to the municipal chamber that the town consisted of 245 buildings and there was no pavement on its streets. The only public buildings where the parish church, and the Rosário and Mercês chapels. Lavras had three private primary schools, with a total of 62 students.[3] According to the 1834 census, Lavras had 11,322 inhabitants.[9]

One of the most significant events of this period was the Liberal Revolution of 1842. For just over a month, between June 14 and July 22, liberals and conservatives kept their barracks in Sant'Ana main square, current Praça Dr. Augusto Silva. The defeated liberals fled or were arrested, subsequently amnestied by the imperial government.[9]

Golden Age

The late nineteenth century and early twentieth century was a time of rapid development in Lavras. On December 18, 1880 it was inaugurated the 208 km river navigation between the Ribeirão Vermelho port (Lavras) and Capetinga port (municipality of Piumhi), made by steamboat "Dr. Jorge ". On April 14, 1888 the Estrada de Ferro Oeste de Minas inaugurated the first station in Ribeirão Vermelho, and, on April 1, 1895, Lavras' city station is inaugurated. Later, in 1911, a tramway was opened, and so Lavras was one of the few cities in Brazilian interior to have this transportation system.[10]

After the Proclamation of the Republic, Lavras established itself as a major regional center of Minas Gerais, being the birthplace of Francisco Salles, an important politician of the Old Republic. At this time, several colleges were created, such as the Evangelical Institute (founded in 1892 by Samuel Rhea Gammon), the College of Our Lady of Lourdes (founded in 1900 by nuns of the Congregation of the Auxiliary Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy), the Lavras School Group (founded in 1907 by Professor Firmino Costa) and the Agricultural School of Lavras (founded in 1908). The quality its education made Lavras to become known as "the city of ipês and schools", a slogan created by journalist Jorge Duarte.[11]

Social and political changes

Local demographics has been modified with the arrival of many immigrants, representing 1.9% of the population according to Census 1920: the municipality had a total of 806 foreigners, of which 380 were Italian, 189 were Portuguese, 166 Lebanese, 28 Spaniards, 20 Americans, 12 Austrians, five French, two Russians, one Uruguayan and three of undetermined nationality.[12]

The 1920s represented a slowdown in Lavras progress, partly caused by the intense political dispute promoted by two distinct groups: the Mineiro Republican Party, under the new direction of Italian doctor Paulo Menicucci, was favorable to the candidacy of Arthur Bernardes to the Presidency and Raul Soares to the Presidency of Minas Gerais; and dissidents, led by Colonel Pedro Sales, supported the respective opposition candidacies of Nilo Peçanha and Francisco Sales. This dispute became known as between "Doves and Hawks": Doves because of effeminate psychasthenics tics attributed to Bernardes, and Hawks for associating the cleverness, the cunning spirit, and, of course, as one of the little dove predators.[9] Such local clash lasted until the following decade, when it was eclipsed by the new national political order — the Estado Novo.

It was in the mid-twentieth century that Lavras constituted its current geographic boundaries. In its administrative division for the year 1933, the municipality was formed by eight districts: Lavras, Carrancas, Ijaci (formerly Conceição do Rio Grande), Ingaí, Itumirim (formerly Rosário), Itutinga (formerly Santo Antônio da Ponte Nova), Luminárias (Nossa Senhora do Carmo das Luminárias) and Ribeirão Vermelho. The municipality has experienced political and administrative separation in 1938, 1943, 1948 and 1962, when their old districts became newly created neighboring municipalities and is currently composed of single district, the urban agglomeration's city.[13]

Progress and stagnation

On the populist period during the Fourth Republic, Lavras development was signaled by new links with major centers: firstly, it was the inauguration of air transport line, that existed between 1947 and 1960;[14][15] secondly was the Lavras-Fernão Dias patch opening to road traffic in 1962. Another aspect of progress was the inauguration of the Itutinga hydroelectric power plant in 1955, which increased electricity production and stimulated industrial growth in the city, through the expansion of existing plants and setting up new ventures.

Lavras, in the 1950s, passed by one of its moments of greatest cultural, artistic and sporting wealth thanks to civic associations such as the Lavras Friends Society (Sal) and Lavrense Society of Artistic Culture (Solca). Chroniclers of the time remember several initiatives such as balls, competitions, exhibitions, educational events, theatrical performances, music recitals and poetry, friendly football tournaments and also the formation of a public library and a city museum.[9]

In the early 1960s, while the country experienced a period of serious institutional crises, Lavras suffered a series of attacks made by a pyromaniac, in which several historical houses were consumed by the flames. In this context, in 1962 the local authorities decided the Municipal Theatre demolition, sealing the end of civic organizations and city's cultural decay. This decline was exacerbated in 1963 by the newspaper A Gazeta disappearance — the only printed weekly at the time — and almost closing of the Agricultural School of Lavras, which was federalized.[16] Other sign of visible social degradation was the Rosary church walls collapse in 1965, difficultly rebuilt only in 1970,[7] and the end of the tramway in 1967.

The 1960s and 1970s represented profound changes in Lavras social composition. On one hand, there was the growth of urban areas due to rural exodus; on the other, it was noted that the city's population growth was below the national average, caused by the phenomenon of internal migration: as Lavras being economically stagnant, many of its children have moved to other centers looking for better opportunities. Another sign of the municipality weakening was the lack of political representation, which would be broken fourteen years later with the election of Maurício Souza Pádua to the Legislative Assembly of Minas Gerais in 1983.

New Millennium

On the eve of the 21st century, Lavras resumed its development path, being currently one of the most prosperous cities in the region, claiming in 2010 the second highest HDI in southern Minas Gerais.[17] This progress is the result of a number of factors, mainly: the installation of the industrial district, which has brought several factories, such as COFAP, inaugurated in February 1988, generating many jobs;[18] the transformation of ESAL into the Federal University of Lavras, in December 1994,[19] whose recent expansion brought thousands of students from other regions of Brazil;[20][21] and the construction of the Funil Hydroelectric Plant in 2002, which changed the countryside by the dam's formed lake.

Nevertheless, this development has also generated new problems in Lavras, such as drug trafficking and increased violence: from 2000-2002 to 2010-2012, the number of homicides caused by firearms increased from 4 to 18.[22][23] Another problem seen today is a major dispute between rival political groups,[24] dividing the city with intensity not seen since the 1920s.

Economy

As 2013, Lavras gross domestic product is R$2,058,203,000, or R$20,965 per capita. Of the GDP, agriculture corresponds to 2.7%, industry to 20.4%, services to 65.3%, while taxes are 11.6%.[25]

Agriculture and Livestock

Lavras agricultural sector stands out especially for the production of coffee and milk, despite the presence of other crops and beef cattle breeding. The production data in 2014 according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics:[26]

| Value (R$ 103) | Area (ha) | Production (t) | Yield (t/ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banana | 120 | 10 | 120 | 12 |

| Coffee | 36,098 | 4,610 | 4,979 | 1.08 |

| Grape | 25 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

| Guava | 160 | 7 | 84 | 12 |

| Orange | 347 | 43 | 559 | 13 |

| Passion fruit | 47 | 3 | 36 | 12 |

| Peach | 25 | 1 | 13 | 13 |

| Value (R$ 103) | Area (ha) | Production (t) | Yield (t/ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bean | 1,230 | 1,000 | 820 | 0.82 |

| Cassava | 54 | 5 | 90 | 18 |

| Corn | 9,720 | 4,000 | 21,600 | 5,400 |

| Soybean | 1,181 | 450 | 1,125 | 2,5 |

| Sugarcane | 275 | 43 | 3,440 | 80 |

| Tomato | 190 | 4 | 200 | 50 |

| Value (R$ 103) | Production | |

|---|---|---|

| Fish | 54 | 9,000 kg |

| Honey | 196 | 28,000 kg |

| Chicken egg | 29,958 | 7,490,000 doz |

| Quail egg | 6,019 | 7,524,000 doz |

| Bovinae | Cows | Galliformes | Chicken | Quail | Equinae | Goat | Sheep | Swine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27,440 | 6,890 | 912,540 | 389,687 | 387,851 | 1,500 | 100 | 550 | 8,500 |

Education

On 2012, Lavras had 31 preschool, 37 primary schools, 16 secondary schools and 3 special education centers. There were 18,671 students and 1,127 teachers. Lavras has also 9 higher education universities and faculties.[27]

| Preschool | Primary schools | Secondary schools | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schools | Teachers | Student | Schools | Teachers | Student | Schools | Teachers | Student | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Municipal School | 21 | 89 | 1721 | 18 | 305 | 6234 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| State School | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 193 | 3671 | 7 | 160 | 3008 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Private School | 10 | 44 | 456 | 11 | 207 | 2394 | 9 | 129 | 1187 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 31 | 133 | 2177 | 37 | 705 | 12299 | 16 | 289 | 4195 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ministério da Educação, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais - INEP - Censo Educacional 2012. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Federal University of Lavras

Lavras has one of Brazil's top universities, the Federal University of Lavras. Founded in 1908 it is well known in Brazil and abroad for its courses in agronomy and veterinary science. There are 6,090 undergraduate students and 2,059 on postgraduate programs.[28]

Transport

Lavras was a station on the Estrada de Ferro Oeste de Minas, a narrow gauge railway.

Sports

Lavras is home of Fabril Esporte Clube, a football club that achieved minor success during the 1980s in Minas Gerais state championship. Some famous athletes were born in Lavras, as the Brazil national football team defenders Alemão and Caçapa and the Bronze medal Olympic winner volleyball player Ana Paula Connelly.

References

- 1 2 IBGE. "Estimativas da população residente 2016". IBGE (in Portuguese). Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Calculadora". Distância entre Cidades. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 Costa, Firmino (1911). "História de Lavras". Revista do Arquivo Público Mineiro (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte: Imprensa Oficial de Minas Gerais. 16 (jan./jun.): 130–131. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Németh-Torres, Geovani (2012). De Parnaíba às Lavras do Funil: Subsídios para a História das Origens de Lavras (e-book) (in Portuguese). Lavras: Geovani Németh-Torres. ISBN 978-85-911368-2-7. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Saint-Adolphe, J. C. Milliet de (1845). Diccionario Geographico, Historico e Descriptivo, do Imperio do Brazil (in Portuguese). 1. Paris: J. P. Aillaud. pp. 556–557. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ São Paulo, Arquivo do Estado de (1896). "Descendência de Amador Bueno de Ribeira". Publicação Oficial de Documentos Interessantes para a História e Costumes de São Paulo (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia Industrial de São Paulo. 4: 27–33. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 Németh-Torres, Geovani (2010). Os 250 Anos da Paróquia de Sant'Ana: Uma História da Igreja Católica em Lavras (in Portuguese). Lavras: Geovani Németh-Torres. ISBN 978-85-911368-0-3. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Provincial Law No. 1510, July 20, 1868.

- 1 2 3 4 Vilela, Marcio Salviano (2007). A Formação Histórica dos Campos de Sant'Ana das Lavras do Funil (in Portuguese). Lavras: Indi.

- ↑ Morrison, Allen (8 April 2012). "The Tramways of Lavras, Minas Gerais state, Brazil". Urban Transport in Latin America. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Duarte, Jorge (24 August 1941). "Lavras, Terra dos Ipês e das Escolas." (in Portuguese). Lavras: A Gazeta.

- ↑ Brasil (1926). Recenseamento do Brazil: realizado em 1 de setembro de 1920, população. (PDF) (in Portuguese). 4–1. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia da Estatística. p. 685. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ IBGE (1959). "Lavras". Enciclopédia dos Municípios Brasileiros (PDF) (in Portuguese). 25. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. pp. 443–450. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Németh-Torres, Geovani (2011). A Atenas Mineira: Capítulos Histórico-Culturais de Lavras. (in Portuguese). Lavras: Geovani Németh-Torres. ISBN 978-85-911368-1-0. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Aeroclube de Lavras. "História" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Federal Law No. 4,307, December 23, 1963. Federaliza a Escola Superior de Agricultura de Lavras (ESAL) e dá outras providências

- ↑ Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento (PNUD) (2010). "Ranking do IDH-M dos municípios do Brasil" (PDF). Atlas do Desenvolvimento Humano (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Alberto da Silva (2002). Gerenciamento eletrônico de documentos: estudo de caso na Magneti Marelli Cofap - Lavras/MG (Monograph) (in Portuguese). Lavras: UFLA. p. 32. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Federal Law No. 8,956, December 15, 1994. Dispõe sobre a transformação da Escola Superior de Lavras em Universidade Federal de Lavras e dá outras providências.

- ↑ Between 1991 and 2010, enrollment in undergraduate higher education in Lavras jumped from 3,066 to 8,366. INEP (2010). "Série Histórica por Município: Número de Cursos, Matrículas, Concluintes, Vagas Oferecidas, Candidatos Inscritos e Ingressos - 1991 a 2010" (Excel). Sinopses Estatísticas da Educação Superior - Graduação (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ In the first semester of 2015, only 20% of students who entered the UFLA were from Lavras. Alvim, Ana Eliza (12 March 2015). "PAS e SiSU: UFLA já recebeu, neste semestre, estudantes de 19 estados e do Distrito Federal". UFLA (in Portuguese). Lavras. ASCOM. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Monteiro, Maria Gabriela; Santa Rosa, Idael Christiano A.; Lopes, Maria Cristina Godinho; Faria, Valdeir Martins de (17 September 2004). "Estudo da mortalidade por causas externas em Lavras, MG" (PDF). XIII Congresso dos Pós-Graduandos da UFLA (in Portuguese). Lavras: UFLA. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Brasil (2015). "Tabelas com a totalidade dos municípios". Mapa da Violência (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Tribunal Regional Eleitoral de Minas Gerais (30 January 2014). "Corte confirma cassação do prefeito de Lavras" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ IBGE (2013). Minas Gerais » Lavras » produto interno bruto dos municípios.

- ↑ IBGE (2014). Minas Gerais » Lavras » informações completas.

- ↑ IBGE (2012). Minas Gerais » Lavras » ensino - matrículas, docentes e rede escolar.

- ↑ Universidade Federal de Lavras. Homepage.

External links

- Prefeitura de Lavras

- Universidade Federal de Lavras

- Centro Universitário de Lavras

- History of Lavras