Leland Stanford

| Leland Stanford | |

|---|---|

|

Stanford c. 1870. | |

| United States Senator from California | |

|

In office March 4, 1885 – June 21, 1893 | |

| Preceded by | James T. Farley |

| Succeeded by | George Clement Perkins |

| 8th Governor of California | |

|

In office January 10, 1862 – December 10, 1863 | |

| Lieutenant | John F. Chellis |

| Preceded by | John G. Downey |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Low |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Amasa Leland Stanford March 9, 1824 Watervliet, New York |

| Died |

June 21, 1893 (aged 69) Palo Alto, California |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Elizabeth Lathrop |

| Children | Leland Stanford, Jr. |

| Alma mater | Cazenovia Seminary |

| Profession | Entrepreneur, politician |

| Signature |

|

Amasa Leland Stanford[1] (March 9, 1824 – June 21, 1893) was an American tycoon, industrialist, politician, and a co-founder (with his wife, Jane) of Stanford University. Migrating to California from New York at the time of the Gold Rush, he became a successful merchant and wholesaler, and continued to build his business empire. He served one two-year term as governor of California after his election in 1861, and later eight years as senator from the state. As president of Southern Pacific Railroad and, beginning in 1861, Central Pacific, he had tremendous power in the region and a lasting impact on California. He is widely considered a robber baron.[2][3][4][5][6]

Biography

Early years

Stanford was born in 1824 in what was then Watervliet, New York (now the Town of Colonie). He was one of eight children of Josiah and Elizabeth Phillips Stanford. Among his siblings were New York State Senator Charles Stanford (1819–1885) and Australian businessman and spiritualist Thomas Welton Stanford (1832–1918). His immigrant ancestor, Thomas Stanford, settled in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in the 17th century.[7] Later ancestors settled in the eastern Mohawk Valley of central New York about 1720.

Stanford's father was a farmer of some means. Stanford was raised on family farms in the Lisha Kill and Roessleville (after 1836) areas of Watervliet. The family home in Roessleville was called Elm Grove. The Elm Grove home was razed in the 1940s. Stanford attended the common schools until 1836 and was tutored at home until 1839. He attended Clinton Liberal Institute, in Clinton, New York, and studied law at Cazenovia Seminary in Cazenovia, New York, in 1841–45. In 1845, he entered the law office of Wheaton, Doolittle and Hadley in Albany.[7]

Career and politics

After being admitted to the bar in 1848, Stanford migrated with many other settlers, moving to Port Washington, Wisconsin, where he began law practice with Wesley Pierce.[8] His father presented him with a law library said to be the finest north of Milwaukee.[7] In 1850, Stanford was nominated by the Whig Party as Washington County, Wisconsin district attorney.

Marriage and family

On September 30, 1850, Stanford married Jane Elizabeth Lathrop in Albany, New York. She was the daughter of Dyer Lathrop, a merchant of that city, and Jane Anne (Shields) Lathrop.[9] The couple did not have any children for years, until their only child, a son, Leland DeWitt Stanford, was born in 1868 when his father was forty-four.[10]

Businesses

In 1852, having lost his law library and other property to a fire, Stanford followed his five brothers to California during the California Gold Rush. His wife, Jane, returned temporarily to Albany and her family. He went into business with his brothers and became the keeper of a general store for miners at Michigan City, California, later the name changed to Michigan Bluff in Placer County; later he had a wholesale house. He served as a justice of the peace and helped organize the Sacramento Library Association, which later became the Sacramento Public Library. In 1855, he returned to Albany to join his wife but found the pace of Eastern life too slow after the excitement of developing California.

In 1856, he and Jane moved to Sacramento, where he engaged in mercantile pursuits on a large scale. Stanford was one of the four major businessmen known popularly as "The Big Four" (or among themselves as "the Associates") who were the key investors in the Central Pacific Railroad, which they incorporated on June 28, 1861, and of which Stanford was elected president. His other three associates were Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, and Collis P. Huntington. They hired Theodore Dehone Judah as the chief engineer.

Stanford ran unsuccessfully for governor of California in 1859. He was nominated again in 1861 and was elected. He served one term, then limited to two years.

The railroad's first locomotive, named "Gov. Stanford" in his honor, is on display today at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.[9][11]

In May 1868, he joined Lloyd Tevis, Darius Ogden Mills, H.D. Bacon, Hopkins, and Crocker in forming the Pacific Union Express Company. It merged in 1870 with Wells Fargo and Company.[12] Stanford was a director of Wells Fargo and Company from 1870 to January 1884. After a brief retirement from the board, he served again from February 1884 until his death in June 1893.[13]

While the Central Pacific was under construction, Stanford and his associates in 1868 acquired control of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Stanford was elected president of the Southern Pacific, a post he held until 1890 (except for a brief period in 1869-70 when Tevis was acting president), when he was ousted by Collis Huntington.

As head of the railroad company that built the western portion of the "First Transcontinental Railroad" over the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, Nevada, and Utah, Stanford presided at the ceremonial driving of "Last Spike" in Promontory, Utah on May 10, 1869. The grade of the CPRR met that of the Union Pacific Railroad, which had been built west from its western terminus at Council Bluffs, Iowa/Omaha, Nebraska.

Stanford moved with his family from Sacramento to San Francisco in 1874, where he assumed presidency of the Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company, the steamship line to Japan and China associated with the Central Pacific.[14]

The Southern Pacific Company was organized in 1884 as a holding company for the Central Pacific-Southern Pacific system. Stanford was president of the Southern Pacific Company from 1885 until 1890, when he was forced out of that post (as well as the presidency of the Southern Pacific Railroad) by Collis Huntington. This was thought to be retaliation for Stanford's election to the United States Senate in 1885 over Huntington's friend, A. A. Sargent.[15]

Stanford was elected chairman of the Southern Pacific Railroad's executive committee in 1890, and he held this post and the presidency of the Central Pacific Railroad until his death.[15]

Other interests

He owned two wineries, the Leland Stanford Winery in Alameda County founded in 1869, and run and later inherited by his brother Josiah, and the 55,000 acres (223 km2) Great Vina Ranch in Tehama County, containing what was then the largest vineyard in the world at 3,575 acres (14 km2) and given to Stanford University.[16]

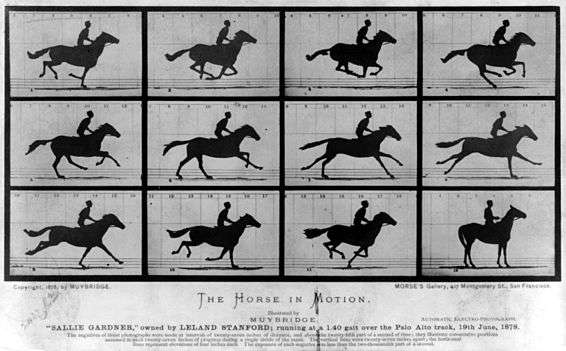

Stanford was also interested in horses and owned the Gridley tract of 17,800 acres (72 km2) in Butte County. In Santa Clara County, he founded his Palo Alto Stock Farm.[17][18] He bred Standardbred horses to be raced as trotters, including his winning horses Electioneer, Arion, Sunol, Palo Alto, Beautiful Bells, and Chimes; and Thoroughbreds for flat racing. In 1872 Stanford commissioned the photographer Eadweard Muybridge to undertake scientific studies of the gaits of horses at a trot and gallop at his Palo Alto Stock Farm. He wanted to determine if they had all four feet off the ground at the same time, which was a question of the day. As the Palo Alto breeding farm was later developed for Stanford University, the university was nicknamed "The Farm."

Stanford was the founder of the insurance company Pacific Life.

Residences

.jpeg)

The Stanfords retained ownership of their mansion in Sacramento, where their only son was born. Now the Leland Stanford Mansion State Historic Park, the house museum is also used for California state social occasions. The Stanfords' home in San Francisco's Nob Hill district was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; the site is occupied now by the Stanford Court Hotel. The Stanford residence at the Palo Alto Stock Farm became a convalescent home for children in 1919 (forerunner of the Lucille Packard Children's Hospital) and was torn down in 1965.[19][20]

Politics

Stanford was politically active and became a leading member of the Republican Party. In 1856, he met with other Whig politicians in Sacramento on April 30 to organize the California Republican Party at its first state convention. He was chosen as a delegate to the Republican Party convention which selected US presidential electors in both 1856 and 1860. Stanford was defeated in his 1857 bid for California state treasurer, and his 1859 bid for the office of governor of California. In 1860, he was named a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago, but did not attend. He was elected governor in a second campaign in 1861.[9]

He was the eighth Governor of California, serving from January 1862 to December 1863, and the first Republican governor. Due to the Great Flood of 1862, the governor was said to have needed to row in a boat to his own inauguration. A large, slow-speaking man who always read from a prepared text, he impressed his listeners as being more sincere than a glib, extemporaneous speaker.[21][22]

During his gubernatorial tenure, he cut the state's debt in half, and advocated for the conservation of forests. He also oversaw the establishment of the California's first state normal school in San José, later to become San José State University. Following Stanford's governorship, the term of office changed from two years to four years, in line with legislation passed during his time in office.

Later, he served in the United States Senate from 1885 until his death in 1893. He served for four years as chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, and also served on the Naval Committee. He authored several Senate bills that advanced ideas advocated by the Populists: a bill to foster the creation of worker-owned cooperatives,[23][24] and a bill to allow the issuance of currency backed by land value instead of only the gold standard.[25][26] Neither bill made it out of committee. In Washington, D.C., he had a residence on Farragut Square near the home of Baron Karl von Struve, Russian minister to the United States.

Racism against the Chinese

The gold strike in California had brought a large influx of newcomers into the territory, including Chinese immigrants. They were persecuted in the gold fields and in small towns and cities, as well because of racial discrimination.[27] Anti-Chinese sentiment became an official political issue over time. Stanford, as governor, ostensibly supported the prevailing mood in the state, which lobbied for the restriction of Chinese immigration. In a message to the legislature in January 1862, Stanford said, “The presence of numbers of that degraded and distinct people would exercise a deleterious effect upon the superior race.”[28] His statement was initially received with widespread enthusiasm, and Stanford was lauded as a defender of the white race. Public opinion shifted when it was revealed that Stanford's Central Pacific Railroad had recruited and imported thousands of Chinese laborers to construct the railway track.[28]

Stanford University

With his wife Jane, Stanford founded Leland Stanford Junior University as a memorial for their only child, Leland Stanford, Jr., who died as a teenager of typhoid fever in Florence, Italy, in 1884 while on a trip to Europe. The University was established by March 9, 1885, Endowment Act of the California assembly and senate, and the Grant of Endowment from Leland and Jane Stanford signed at the first meeting of the board of trustees on November 14, 1885.[29]

The Stanfords donated approximately US$40 million[30] (over $1 billion in 2010 dollars) to develop the university, which held its opening exercises October 1, 1891. It was intended for agricultural studies. Its first student, admitted to Encina Hall that day, was Herbert Hoover. The wealth of the Stanford family during the late 19th century is estimated at about $50 million (about $1.3 billion in 2010 dollars).

Worker Cooperatives

Stanford had ideas of employee ownership for more than thirty years before giving them expression in his plans for Stanford University, proposals as a Senator, and in interviews with the news media.[31]

Personal life

Leland Stanford was an active freemason from 1850 to 1855, joining the Prometheus Lodge No. 17 in Port Washington, Wisconsin. After moving west, he became a member of the Michigan City Lodge No. 47 in Michigan Bluff, California.[32] He was also a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows in California.

Long suffering from locomotor ataxia, Leland Stanford died of heart failure at home in Palo Alto, California, on June 21, 1893.[33] He was buried in the family mausoleum on the Stanford campus. Jane Stanford died in 1905 after being poisoned with strychnine.[34][35]

Legacy and honors

- In 1862 California volunteer troops re-building a military post at the confluence of the San Pedro River and Aravaipa Creek in Arizona Territory named the post Fort Stanford after the governor. However, the post later reverted to its former name, Fort Breckenridge, and in 1866 became Camp Grant.

- Central Pacific locomotives named for Stanford[36][37] were:

- Gov. Stanford, a 4-4-0 locomotive built in 1863 by the Norris Locomotive Works in Philadelphia and brought to San Francisco by sailing vessel. This engine is preserved at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

- El Gobernador, a 4-10-0 locomotive built in the Central Pacific shops in Sacramento in 1884. Found to be disappointing in its performance as a freight hauler, it was scrapped in July 1894.

- The Stanford Memorial Church on the university campus is dedicated to him.

- 2008, Stanford was inducted into the The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts, California Hall of Fame. A relative Tom Stanford accepted the honors on his behalf.[38]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Burlingame, Dwight (August 19, 2004). Philanthropy in America: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 456. ISBN 978-1-57607-860-0.

- ↑ Tuterow, Norman E. The governor: the life and legacy of Leland Stanford, a California colossus, Volume 2. (2004: Arthur H. Clark Co.2004) page 1146.

- ↑ Carlisle, Rodney P. (editor). Handbook to Life in America, Vol. 4. (April 2009: Facts on File) page 8.

- ↑ Cummings, Bruce. "Dominion from Sea to Sea: Pacific Ascendancy and American Power." (2009: Yale University Press.) page 672.

- ↑ Lindsay, David. Madness in the Making. (2005: Universe.) page 214.

- ↑ Goethals, George R. et al. Encyclopedia of Leadership, Vol. I. (2004: Sage Publications.) page 897.

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. XVII, p. 501. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1935.

- ↑ "LandmarkHunter.com - Port Washington Downtown Historic District". landmarkhunter.com.

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. XVII, p. 502.

- ↑ "Jane Stanford: The woman behind St". Stanford University. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Keith Wheeler, The Railroaders, pp. 60-61. New York: Time-Life Books, 1973.

- ↑ Noel M. Loomis, Wells Fargo, pp. 199-200. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1968.

- ↑ Loomis, pp. 215, 255, 270.

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol. II, p. 129. New York: James T. White & Company, 1899. Reprint of 1891 edition.

- 1 2 Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. XVII, pp. 503, 504.

- ↑ Thomas Pinney, 1989, A History of Wine in America from the Beginnings to Prohibition, Volume 1, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06224-5

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, op. cit.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. XVII, p. 504.

- ↑ https://www.lpch.org/aboutus/HistoryAndMission/index.html

- ↑ "Jane L. Stanford: Timeline - Stanford University". stanford.edu.

- ↑ Cleveland Amory, Who Killed Society?, p. 430. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960

- ↑ Wheeler, p. 56.

- ↑ Stanford, Leland, 1887. Co-operation of Labor, New York Tribune, May 4, 1887. Special Collection 33a, Box 7, Folder 74, Stanford University Archives. PDF

- ↑ Congressional Record, 49 Congress, 2 Sess.: 1804-1805; 51 Congress, 1 Sess.: 2068-2069, 5169-5170, 2 Sess.: 667-668; 52 Congress, 1 Sess.: 468-479, 2684-2686.

- ↑ The Land Loan Project: Senator Stanford Explains His New Money Scheme, New York Times March 31, 1892.

- ↑ "The great question : an interview with senator Leland Stanford on money.". worldcat.org.

- ↑ Asbury, Herbert, The Barbary Coast, Basic Books, 2008, p. 143

- 1 2 Asbury, Herbert, The Barbary Coast, Basic Books, 2008, p. 145

- ↑ The Leland Stanford, Junior, University. The Act of the Legislature of California. The Grant of Endowment. Address of Leland Stanford to the Trustees. Minutes of the First Meeting of Board of Trustees.

- ↑ "Stanford Estate Worth Seven Millions". The Evening News. 5 April 1905.

- ↑ Altenberg,Lee "Beyond Capitalism: Leland Stanford's Forgotten Vision," Sandstone and Tile, Vol. 14 (1): 8-20, Winter 1990, Stanford Historical Society, Stanford, California. http://dynamics.org/~altenber/PAPERS/BCLSFV/, accessed June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Denslow, William (June 15, 2007) [1957]. 10,000 Famous Freemasons (papernack). IV. New Orleans: Cornerstone Book Publishers. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-887560-06-1.

- ↑ Kate Field's Washington Vol. 7, No. 26. June 28, 1893. p. 403

- ↑ National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, op. cit.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. XVII, pp. 504, 505.

- ↑ Stephen E. Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World. The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869, pp. 115, 117. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

- ↑ Brian Hollingsworth, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of North American Locomotives, pp. 40-41. New York: Crescent Books, 1984.

- ↑ Bruce Dancis, "New California Hall of Fame class includes Fonda, Nicholson", Sacramento Bee, May 28, 2008.

References

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Stanford, Leland". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Stanford, Leland". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leland Stanford. |

- Governor Leland Stanford biography at the California State Library

- Beyond Capitalism: Leland Stanford's Forgotten Vision, by Lee Altenberg, Sandstone and Tile, 1990, Stanford Historical Society

- United States Congress. "Leland Stanford (id: S000793)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Penny Postcards: Leland Stanford's store: Michigan Bluff, California

- Stanford's racist speech: "Leland Stanford promised in his inaugural address to protect the state from "the dregs of Asia" -PBS.org

- Leland Stanford at Find a Grave

- The Philanthropy Hall of Fame, Leland Stanford

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John G. Downey |

Governor of California January 10, 1862 – December 10, 1863 |

Succeeded by Frederick Low |

| Preceded by James T. Farley |

U.S. Senator (Class 3) from California March 4, 1885 – June 21, 1893 Served alongside: John F. Miller, George Hearst, Charles N. Felton, Stephen M. White |

Succeeded by George C. Perkins |

| Business positions | ||

| Preceded by None |

Executive Committee Chairmen Southern Pacific Railroad 1890–1893 |

Succeeded by Robert S. Lovett |