Li gui

The Li gui (Chinese: 利簋) is an ancient Chinese bronze sacrificial gui vessel cast by an early Zhou dynasty official named Li. It has the distinction of being the earliest Zhou bronze vessel to be discovered,[1] the earliest record of metal being given as a gift by the king,[2] one of only two vessels dateable to the reign of King Wu of Zhou to record personal names,[3] and the only epigraphic evidence of the day of the Zhou conquest of Shang.[4] This makes the Li gui highly important to the periodisation of the Shang and Zhou dynasties, and it has been described as bearing "the single most important inscription regarding the Zhou conquest of Shang."[5]

A round vessel on a square pedestal, the Li gui measures 28 centimeters high; the mouth of the vessel has a diameter of 22 centimeters. It has two bird-shaped handles and is covered with a high-relief taotie motif similar to earlier Shang ritual objects.[6] It was excavated in 1976 in Lintong district, Shaanxi, and was kept for a time at the Lintong County Museum, before being transferred to the National Museum of China in Beijing, where it now resides. In 2002, it was listed among the cultural artefacts prohibited from leaving Chinese soil.[7]

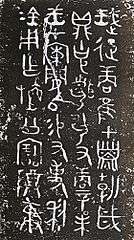

Inscription

The Li gui is inscribed with thirty-two graphs commemorating King Wu of Zhou's conquest of Shang. The most important feature of the inscription is the record of the cylical signs of the day of the decisive Battle of Muye. The inscription accords with the date carried by the Shi Fu (世俘, "capture of the world") chapter of the Yi Zhou Shu,[8] and the Mu Shi (牧誓, "Speech at Muye") chapter of the Book of Documents.[9] The inscription begins: "King Wu attacked Shang. It was the morning of the jiazi day." King Wu's name thus recorded on a contemporary vessel supports the theory that the early Zhou kings were called by the same titles in life as they were after their deaths, unlike later Chinese monarchs.[10]

The next several graphs are the subject of much dispute in interpretation, most saliently over whether to read the word sui (歲, the bottom-rightmost graph in the inscription) as the name of a ritual or as a reference to the planet Jupiter.[11] There is no scholarly consensus on the meaning of this portion of the inscription, with renderings ranging from "Jupiter was in the correct position, letting the King know he would conquer, and soon he controlled Shang"[12] to "The King performed the sui and ding sacrifices, letting it be known that he could rout the ruler of Shang."[13]

Following the problematic passage, the inscription concludes: "On the xinwei day [i.e. seven days later], the King was at Jian[14] encampment. He granted his youshi[15] Li metal, with which he makes this treasured ritual vessel for his esteemed ancestor Zhan."[16] This indicates that Li, the caster of the vessel, may have been a participant in the Battle of Muye.[17]

Notes

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1989), p 51

- ↑ Cook, p 267

- ↑ Xie, p 75

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1991), p 87

- ↑ Li Feng, p 48

- ↑ So, p 16

- ↑ The Chinese Cultural Heritage Protection Web Site (in Chinese)

- ↑ Yi Zhou Shu, 40.439

- ↑ Speech at Muye, with translation by James Legge

- ↑ Shirakawa, p 325, citing Tang Lan (唐蘭) (1977)

- ↑ Shirakawa summarises the various proposed translations pp 320–28; Shaughnessy (1991) illustrates the different interpretations on a graph-by-graph basis, then translates each individually, pp 92–4. Shaughnessy (1991), pp 92–104, is the most thorough English treatment of the inscription, though it antedates several Chinese translations.

- ↑ Chinese Archaeology, pp 196–7

- ↑ Shirakawa, p 325

- ↑ The reading jian for this graph was proposed by Yu Xingwu. It is a toponym that appears in other inscriptions, and appears to have been part of the Shang royal demesne near the capital. See Shirakawa, p 324.

- ↑ Youshi is read variously as 又事 or 右史. Cook renders this title as "aiding ritualist"; Shaughnessy gives "chargé d'affaires", which has the drawback of still not being English. See Cook, p 267; Shaughnessy (1991), p 87

- ↑ Zhan (旜) may be Li's family name, or it may be his home state. The two interpretations are not exclusive, but if it is a toponym, 旜公 may also be rendered "the Lord of Zhan". Zhan may also be identical to 檀 (tan), as suggested by Tang Lan. See Shaughnessy (1991), p 91

- ↑ See Shirakawa, p 325, citing Tang Lan; Cook, p 267 n 104

References

- Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed. (2001). 殷周金文集成釋文 [Transcribed Texts of Collected Shang and Zhou Bronze Inscriptions]. 3. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Chinese Culture University Press. p. 287. ISBN 962-996-041-9.

- Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed. (2004). 中國考古學: 兩周卷 [Chinese Archaeology: Western Zhou and Eastern Zhou]. Beijing: Chinese Social Science Press. ISBN 7-5004-4871-6.

- Huang Huaixin (黃懷信), Zhang Yirong (張懿鎔), Tian Xudong (田旭東), eds. (1995). 逸周書彙校集注 [Yizhoushu, with Collected Annotation and Exegesis]. Shanghai Guji Publishing.

- Cook, Constance A. (1997). "Wealth and the Western Zhou". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Cambridge University Press. 60 (2): 253–294. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00036399. JSTOR 620385.

- Li Feng (2006). Landscape and Power in Early China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521852722.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1989). "The Role of Grand Protector Shi in the Consolidation of the Zhou Conquest". Ars Orientalis. 19: 51–77.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1991). Sources of Western Zhou History. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 87–105. ISBN 0-520-07028-3.

- Shirakawa Shizuka (白川靜) (1962–84). "50". 金文通釋 [Complete Explanations of Bronze Inscriptions] (in Japanese). 6. Kobe: Hakutsuru bijutsukan. pp. 317–29.

- So, Jenny F. (2008). "Antiques in Antiquity: Early Chinese looks at the past". Journal of Chinese Studies. The Chinese University of Hong Kong (48).

- Xie Bolin (謝博霖) (2012). 西周青銅器銘文人名及斷代研究 [Research into names and dates inscribed on Western Zhou bronzes] (Master's thesis) (in Chinese). National Chengchi University, Taibei.