The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

| The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp | |

|---|---|

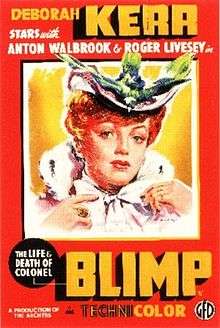

Cinema poster | |

| Directed by |

Michael Powell Emeric Pressburger |

| Produced by |

Michael Powell Emeric Pressburger |

| Written by |

Michael Powell Emeric Pressburger |

| Starring |

Deborah Kerr Roger Livesey Anton Walbrook |

| Music by | Allan Gray |

| Cinematography | Georges Perinal |

| Edited by | John Seabourne Sr. |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

General Film Distributors (UK) United Artists (US) |

Release dates |

(UK) |

Running time | 163 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £200,000 or US$2 million[1] |

| Box office | $275,472 (US)[2] |

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is a 1943 romantic drama war film written, produced and directed by the British film making team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger under the production banner of The Archers. It stars Roger Livesey, Deborah Kerr and Anton Walbrook. The title derives from the satirical Colonel Blimp comic strip by David Low but the story itself is original. The film is renowned for its Technicolor cinematography.

Plot

Major-General Clive Wynne-Candy (Roger Livesey) is a senior commander in the Home Guard during the Second World War. Before a training exercise, he is "captured" in a Turkish bath by soldiers led by Lieutenant "Spud" Wilson, who has struck pre-emptively. He ignores Candy's outraged protests that "War starts at midnight!" They scuffle and fall into a bathing pool.

An extended flashback ensues.

Boer War

In 1902, Lieutenant Candy is on leave from the Boer War. He has received a letter from Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr), who is working in Berlin. She complains that a German named Kaunitz is spreading anti-British propaganda, and she wants the British embassy to do something about it. When Candy brings this to his superiors' attention, they refuse him permission to intervene, but he decides to act anyway.

In Berlin, Candy and Edith go to a café, where he confronts Kaunitz. Provoked, Candy inadvertently insults the Imperial German Army officer corps. The Germans insist he fight a duel with an officer chosen by lot: Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook). Candy and Theo become friends while recuperating from their wounds in the same nursing home. Edith visits them both regularly and, although it is implied that she has feelings for Clive,[3] she becomes engaged to Theo. Candy is delighted, but soon realises to his consternation that he loves her himself.

First World War

Candy, now a brigadier general, believes that the Allies won the First World War because "right is might". While in France, he meets nurse Barbara Wynne (Kerr again). She bears a striking resemblance to Edith. Back in England, he courts and marries her despite their twenty-year age difference.

Candy tracks Theo down at a prisoner of war camp in England. Candy greets him as if nothing has changed, but Theo snubs him. Later, about to be repatriated to Germany, Theo apologises and accepts an invitation to Clive's house. He remains sceptical that his country will be treated fairly.

Barbara dies between the world wars, and Candy retires in 1935.

Second World War

In 1939, Theo relates to an immigration official how he was estranged from his children when they became Nazis. Before the war, he had refused to move to England when Edith wanted to; by the time he was ready, she had died. Candy vouches for Theo.

Candy reveals to Theo that he loved Edith and only realised it after it was too late. He admits that he never got over it. He shows Theo a portrait of Barbara. Theo then meets Candy's MTC driver, Angela "Johnny" Cannon (Kerr again), personally chosen by the Englishman; Theo is struck by her resemblance to Barbara and Edith.

Candy, restored to the active list, is to give a BBC radio talk regarding the retreat from Dunkirk. Candy plans to say that he would rather lose the war than win it using the methods employed by the Nazis: his talk is cancelled at the last minute. Theo urges his friend to accept the need to fight and win by whatever means are necessary, because the consequences of losing are so dire.

Candy is again retired, but, at Theo's and Angela's urging, he turns his energy to the Home Guard. Candy's energy and connections are instrumental in building up the Home Guard. His house is bombed in the Blitz and is replaced by an emergency water supply cistern. He moves to his club, where he relaxes in a Turkish bath before a training exercise he has arranged.

The film has now come full circle. The brash young lieutenant who captures Candy is in fact Angela's boyfriend, who used her to learn about Candy's plans and location. She tries to warn Candy, but is too late.

Afterward, Theo and Angela find Candy sitting across the street from where his house once stood. He recalls that after being given a severe dressing down by his superior for causing the diplomatic incident, he had declined the man's invitation to dinner, and had often regretted doing so. He tells Angela to invite her boyfriend to dine with him.

Years before, Clive had promised Barbara that he would "never change" until his house is flooded and "this is a lake". Seeing the cistern, he realises that "here is the lake and I still haven't changed". The film ends with Candy saluting the new guard as it passes by.

Cast

|

|

Cast notes:

- Making their second appearance in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp were director Michael Powell's golden cocker spaniels, Erik and Spangle, who had previously appeared in Contraband (1940), and went on to be seen in the Powell and Pressburger films I Know Where I'm Going! (1945) and A Matter of Life and Death (US: Stairway to Heaven, 1946).[4]

Production

According to the directors, the idea for the film did not come from the newspaper comic strip by David Low but from a scene cut from their previous film, One of Our Aircraft Is Missing, in which an elderly member of the crew tells a younger one, "You don't know what it's like to be old." Powell has stated that the idea was actually suggested by David Lean (then an editor) who, when removing the scene from the film, mentioned that the premise of the conversation was worthy of a film in its own right.[5]

Powell wanted Laurence Olivier (who had previously appeared in Powell and Pressburger's 49th Parallel and The Volunteer) to play Candy however the Ministry of Information refused to release Olivier, who was serving in the Fleet Air Arm, from active service telling Powell and Pressburger, "...we advise you not to make it and you can't have Laurence Olivier because he's in the Fleet Air Arm and we're not going to release him to play your Colonel Blimp".[6]

Powell wanted Wendy Hiller to play Kerr's parts but she pulled out due to pregnancy. The character of Frau von Kalteneck, a friend of Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff, was played by Roger Livesey's wife Ursula Jeans; although they often appeared on stage together this was their only appearance together in a film.

Further problems were caused by Prime Minister Winston Churchill who, prompted by objections from James Grigg, his secretary of state for war, sent a memo suggesting the production be stopped. Grigg warned that the public's belief in the "Blimp conception of the Army officer" would be given "a new lease of life".[7] After Ministry of Information and War Office officials had viewed a rough cut, objections were withdrawn in May 1943. Churchill's disapproval remained, however, and at his insistence an export ban, much exploited in advertising by the British distributors, remained in place until August of that year.[7]

The film was shot in four months at Denham Film Studios and on location in and around London, and at Denton Hall in Yorkshire. Filming was made difficult by the wartime shortages and by Churchill's objections leading to a ban on the production crew having access to any military personnel or equipment. But they still managed to "find" quite a few Army vehicles and plenty of uniforms.

Michael Powell once said of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp that it is

... a 100% British film but it's photographed by a Frenchman, it's written by a Hungarian, the musical score is by a German Jew, the director was English, the man who did the costumes was a Czech; in other words, it was the kind of film that I've always worked on with a mixed crew of every nationality, no frontiers of any kind."[8]

At other times he also pointed out that the designer was German, and the leads included Austrian and Scottish actors.

Original release and contemporary reception

The film was released in the UK in 1943. The première, organised by Lady Margaret Alexander, took place on 10 June at the Odeon cinema, Leicester Square, London, with all proceeds donated to the Odeon Services and Seamen's Fund.[9] The film was heavily attacked on release mainly because of its sympathetic presentation of a German officer, albeit an anti-Nazi one, who is more down-to-earth and realistic than the central British character. Sympathetic German characters had previously appeared in the films of Powell and Pressburger, for example The Spy in Black and 49th Parallel, the latter of which was also made during the war.

The film provoked an extremist pamphlet, The Shame and Disgrace of Colonel Blimp, by "right-wing sociologists E. W. and M. M. Robson", members of the obscure Sidneyan Society:

[A] highly elaborate, flashy, flabby and costly film, the most disgraceful production that has ever emanated from a British film studio.

The film was the fourth most popular movie at the British box office in 1943.[10]

Due to the British government's disapproval of the film, it was not released in the United States until 1945 and then in a modified form, as The Adventures of Colonel Blimp or simply Colonel Blimp. The original cut was 163 minutes. It was reduced to a 150-minute version, then later to 90 minutes for television. One of the crucial changes made to the shortened versions was the removal of the film's flashback structure.[11]

Restorations

In 1983, the original cut was restored for a re-release, much to Emeric Pressburger's delight. Pressburger, as affirmed by his grandson Kevin Macdonald on a Carlton Region 2 DVD featurette, considered Blimp the best of his and Powell's works.

Nearly thirty years later, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp underwent another restoration similar to that performed on The Red Shoes. The fundraising was spearheaded by Martin Scorsese and his long-time editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, also Michael Powell's widow. Restoration work was completed by the Academy Film Archive[12] in association with the BFI, ITV Studios Global Entertainment Ltd. (the current copyright holders), and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by The Material World Charitable Foundation, the Louis B. Mayer Foundation, Cinema per Roma Foundation, and The Film Foundation. The restored version premièred in New York on 6 November 2011, followed by a screening in London on 30 November.

The restored film is being shown around the world[13] and was released on DVD & Blu-ray on 22 October 2012.[14]

Reputation and analysis

Although the film is strongly pro-British, it is a satire on the British Army, especially its leadership. It suggests that Britain faced the option of following traditional notions of honourable warfare or to "fight dirty" in the face of such an evil enemy as Nazi Germany.[15][16] There is also a certain similarity between Candy and Churchill and some historians have suggested that Churchill may have wanted the production stopped because he had mistaken the film for a parody of himself (he had himself served in the Boer War and the First World War).[17][18] Churchill's exact reasons remain unclear, but he was acting only on a description of the planned film from his staff, not on a viewing of the film itself.

Since the highly successful re-release of the film in the 1980s, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp has been re-evaluated.[19] The film is praised for its dazzling Technicolor cinematography (which, with later films such as The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus, would become The Archers' greatest legacy), the performances by the lead actors as well as for transforming, in Roger Ebert's words; "a blustering, pigheaded caricature into one of the most loved of all movie characters".[20] David Mamet has written: "My idea of perfection is Roger Livesey (my favorite actor) in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (my favorite film) about to fight Anton Walbrook (my other favorite actor)."[21] Stephen Fry saw the film as addressing "what it means to be English", and praised it for the bravery of taking a "longer view of history" in 1943.[22] Anthony Lane of the New Yorker said in 1995 that the film "may be the greatest English film ever made, not least because it looks so closely at the incurable condition of being English".[23]

The film currently has a rating of 95% on Rotten Tomatoes and also appears in Empire magazine's list of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time at number 80.[24]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ "Indies $70,000,000 Pix Output". Variety: 3. 3 November 1944. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Sarah Street, Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA, Continuum, 2002 p 97

- ↑ This is suggested by Michael Powell in the DVD commentary track.

- ↑ Erik at the Internet Movie Database, Spangle at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Michael Powell, commentary on the Criterion Collection Laserdisc (also available on the Criterion DVD)

- ↑ Chapman, James. "'The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp' reconsidered.". The Powell & Pressburger Pages. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- 1 2 Aldgate, Anthony; Richards, Jeffrey (1999). Best of British. Cinema and Society (2 ed.). London: I. B. Taurus. ISBN 978-1-86064-288-3.

- ↑ Ian Christie, "Powell and Pressburger", 1985; in David Lazar, Michael Powell: Interviews, 2003. ISBN 1-57806-498-8

- ↑ "Film of "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp"". The Times. London. 3 June 1943. p. 7.

- ↑ Robert Murphy, Realism and Tinsel: Cinema and Society in Britain 1939-48 2003 p 206

- ↑ As may be seen in the shortened version available at some national libraries like the BFI

- ↑ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

- ↑ Screenings 2012

- ↑ Amazon (UK)

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/LifeAndDeathOfColonelBlimp_the

- ↑ As is shown in the film in Theo's speech to Clive after Clive's broadcast is cancelled

- ↑ Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (1994). Ian Christie, ed. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-14355-5.

- ↑ A. L. Kennedy (1997). The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. BFI. ISBN 0-85170-568-5.

- ↑ Chapman, James (March 1995). "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp: reconsidered.". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. pp. 19–36.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (27 October 2002). "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943)". rogerebert.suntimes.com.

- ↑ David Mamet, Bambi vs. Godzilla, 2007, p. 148

- ↑ Stephen Fry, interviewed by the Daily Telegraph, 2003

- ↑ Anthony Lane, The New Yorker, 20 March 1995

- ↑ http://www.empireonline.com/500/83.asp

- Bibliography

- Chapman, James. "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp: reconsidered." Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 03/95 15(1) pp. 19–36.

- Christie, Ian. "The Colonel Blimp File." Sight and Sound, 48. 1978

- Includes the contents of Public Record Office file on the film

- Christie, Ian. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (script) by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger. London: Faber & Faber, 1994. ISBN 0-571-14355-5.

- Includes the contents of Public Record Office file on the film, memos to & from Churchill and the script showing the difference between the original and final versions

- Kennedy, A.L. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. London: BFI Film Classics, 1997. ISBN 0-85170-568-5.

- Powell, Michael. A Life in Movies: An Autobiography. London: Heinemann, 1986. ISBN 0-434-59945-X.

- Powell, Michael. Million Dollar Movie. London: Heinemann, 1992. ISBN 0-434-59947-6.

- Vermilye, Jerry. The Great British Films. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1978. pp66–68. ISBN 0-8065-0661-X.

External links

- The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp at the Internet Movie Database

- The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp at the TCM Movie Database

- The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp at AllMovie

- The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp at the British Film Institute's Screenonline. Full synopsis and film stills (and clips viewable from UK libraries).

- BFI's Top Fifty (British) Films

- Blimp material at the Powell & Pressburger Appreciation Society

- BBC Radio 4 programme on the film with contributions by Martin Scorsese, Thelma Schoonmaker, Kevin Macdonald (director) and Ian Christie.

- The Shame and Disgrace of Colonel Blimp

- DVD reviews

- Region 2 UK – Carlton DVD

- Region 2 France – Warner Home Vidéo / L'Institut Lumière

- Review by John White at DVD Times (UK)

- Region 1 USA – Criterion Collection

- DVD comparisons

- DVD Beaver comparison of Carlton & Criterion releases

- Celtoslavica comparison of Carlton & Criterion releases