List of lingua francas

This is a list of lingua francas. A lingua franca (English plural lingua francas, although the pseudo-Latin form linguae francae is also seen) is a language systematically used to make communication possible between people not sharing a first language, in particular when it is a third language, distinct from both speakers' first languages. Examples of lingua francas are numerous, and exist on every continent. The most obvious modern example is English, which is the current dominant lingua franca of international diplomacy, business, science, technology and aviation. There are many other lingua francas centralized on particular regions, such as Arabic, Chinese, French, Russian and Spanish.

The popularity of languages changes over time, and there are many lingua francas that are of historical importance. These include French, which was the language of European diplomacy from the 17th until the mid-20th century, and Classical Chinese, which served as both the written lingua franca and the diplomatic language in Far East Asia until the early 20th century. French and Chinese are still significant lingua francas today.

Africa

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is spoken as a first language by millions of people in South Africa, and as a second language by millions more. During apartheid, the South African government aimed to establish it as the primary 'lingua franca' in South Africa and South African-controlled South-West Africa (now Namibia), although English was also in common use. Since the end of apartheid, English has been widely adopted as the sole lingua franca. Many institutions that had names in English and Afrikaans have since dropped the Afrikaans names. Notable cases are South African Airways and the South African Broadcasting Corporation. Afrikaans is still widely used, especially by the adult population. However, English is becoming more popular among the younger generation. This is having an impact on Afrikaans, with an increase in English loanwords.

In Namibia, Afrikaans holds a more universal role than in South Africa, across ethnic groups and races and is the spoken lingua franca in the capital Windhoek and throughout most of central and southern Namibia. There are pockets where German is commonly spoken. English is the sole official language, but its role as a lingua franca is second to Afrikaans.

Amharic

Amharic is widely spoken in Ethiopia. It is an official national language, and thereby serves as a lingua franca for the many different local populations.[1]

Arabic

There are more Arabic speakers in Africa than Asia. It is spoken as an official language in all of the continent's Arab League states. Arabic is also spoken as a trade language across the Sahara as far as the Sahel, including parts of Mali, Chad and Borno State in Nigeria.

Berber

During the rise of Berber dynasties like the Almoravids and Almohads between 1040 and 1500, Berber served as both the vernacular and lingua franca of Northwest Africa. Today the language is less influential due to its suppression and marginalization, and the adoption of French and Arabic by the political regimes of the Berber world as working languages. However, Tuareg, a branch of the Berber languages, is still playing the role of a lingua franca to some extent in some vast parts of the Sahara Desert, especially in southern Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Libya. Another branch, Tamazight, has become an official language of Morocco. In Algeria, Tamazight has been a national language since 2002, and an official State Language in 2016.

Fanagalo

Fanagalo or Fanakalo is a pidgin based on the Zulu, English, and Afrikaans languages. It was used as a lingua franca mainly in the mining industries in South Africa, however in this role it is being increasingly eclipsed by English which is viewed as being more neutral politically.[2]

Fula

Fula (Fula: Fulfulde or Pulaar or Pular, depending on the region; French: Peul) the language of the Fula people or Fulani (Fula: Fulɓe; French: Peuls) and associated groups such as the Toucouleur. Fula is spoken in all countries directly south of the Sahara (such as Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria, Niger, Mali...). It is spoken mainly by Fula people, but is also used as a lingua franca by several populations of various origin, throughout Western Africa.

Hausa

Hausa is widely spoken through Nigeria and Niger and recognised in neighbouring states such as Ghana, Benin, and Cameroon. The reason for this is that Hausa people used to be traders who led caravans with goods (cotton, leather, slaves, food crops etc.) through the whole West African region, from the Niger Delta to the Atlantic shores at the very west edge of Africa. They also reached North African states through Trans-Saharan routes. Thus trade deals in Timbuktu in modern Mali, Agadez, Ghat, Fez in Northern Africa, and other trade centers were often concluded in Hausa.

Krio

Krio is the most widely spoken language throughout Sierra Leone even though its native speakers, the Sierra Leone Creole people or Krios (a community of about 300,000 descendants of formerly enslaved people from the West Indies, United States and Britain), make up only about 5% of the country's population. The Krio language unites all the different ethnic groups, especially in their trade and interaction with each other. Krio is also spoken in The Gambia.

Lingala

Lingala is used by over 10 million speakers throughout the northwestern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a large part of the Republic of the Congo, as well as to some degree in Angola and the Central African Republic, although it has only about two million native speakers.[3] Its status is comparable to that of Swahili in eastern Africa.

Between 1880 and 1900, the colonial administration, in need of a common language for the region, adopted a simplified form of Bobangi, the language of the Bangala people, which became Lingala. Spoken Lingala has many loanwords from French, inflected with Lingala affixes.

Manding

The largely interintelligible Manding languages of West Africa serve as lingua francas in various places. For instance Bambara is the most widely spoken language in Mali, and Jula (almost the same as Bambara) is commonly used in western Burkina Faso and northern Côte d'Ivoire. Manding languages have long been used in regional commerce, so much so that the word for trader, jula, was applied to the language currently known by the same name. Other varieties of Manding are used in several other countries, such as Guinea, The Gambia, and Senegal.

Sango

The Sango language is a lingua franca developed for intertribal trading in the Central African Republic. It is based on the Northern Ngbandi language spoken by the Sango people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo but with a large vocabulary of French loan words. It has now been institutionalised as an official language of the Central African Republic.

Swahili

Swahili, known as Kiswahili to its speakers, is used throughout large parts of East Africa and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo as a lingua franca, despite being the mother tongue of a relatively small ethnic group on the East African coast and nearby islands in the Indian Ocean. At least as early as the late 18th century, Swahili was used along trading and slave routes that extended west across Lake Tanganyika and into the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo. Swahili rose in prominence throughout the colonial era, and has become the predominant African language of Tanzania and Kenya. Some ethnic groups now speak Swahili more often than their mother tongues, and many, especially in urban areas, choose to raise their children with Swahili as their first language, leading to the possibility that several smaller East African languages will fade away as Swahili transitions from being a regional lingua franca to a regional first language.

It has official status as a national language in DR Congo, Tanzania and Kenya, and symbolic official status (understood but not widely spoken) in Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. It is the first language of education in Tanzania and in much of eastern Congo. It is also the auxiliary language to be in the proposed East African Federation.

Wolof

Wolof is a widely spoken lingua franca of Senegal and The Gambia (especially the capital, Banjul). It is the native language of approximately 5 million Wolof people in Senegal, and is spoken as a second language by an equal number.

Asia

Akkadian

In the Middle East, from around 2600BCE to 1500BCE, forms of Akkadian were the universally recognized language. It was used throughout the Akkadian empire as well as internationally as a diplomatic language — for example between Egypt and Babylon — well after the fall of the Akkadian empire itself and even while Aramaic was more common in Babylon.

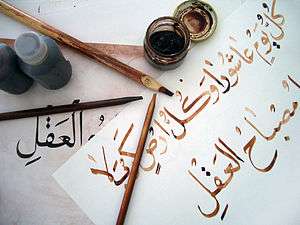

Arabic

Arabic, the native language of the Arabs, who originally came from the Arabian Peninsula, became the "lingua franca" of the Islamic (Arab) Empire (from CE 733 – 1492), which at its greatest extent included the borders of China and Northern India, Central Asia, Persia, Asia Minor, the Middle East, North Africa, Spain and Portugal.

During the Islamic Golden Age (around CE 1200), Arabic was the language of science and diplomacy. Arabic loanwords are found in many languages, including English, Persian, Turkish, Hindustani, Somali, Spanish, Portuguese and Swahili. In Iberia, this is a legacy of the Al-Andalus period. Additionally, Arabic was used by people neighbouring the Islamic Empire.

Arabic script was adopted by many other languages such as Urdu, Persian, Swahili (changed to Latin in the late 19th century), Turkish (switched to Latin script in 1928), and Somali (changed to Latin in 1972). Arabic became the lingua franca of these regions not simply because of commerce or diplomacy, but also on religious grounds since Arabic is the language of the Qur'an, Islam's holy book and these populations became heavily Muslim. Arabic remains the lingua franca for 23 countries (25 with the Palestinian territories and Western Sahara), in the Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa, in addition to Chad and Eritrea. Despite a few language script conversions from Arabic to Latin as just described, Arabic is the second most widely used alphabetic system in the world after Latin.[4] Arabic script is/has been used in languages including Afrikaans, Azeri, Bosnian, Hausa, Kashmiri, Kazakh, Kurdish, Kyrgyz, Malay, Morisco, Pashto, Persian, Punjabi, Sindhi, Somali, Tatar, Turkish, Turkmen, Urdu, Uyghur, and Uzbek.[5]

According to Encarta, which classified Chinese as a single language, Arabic is the second largest native language.[6] Used by more than a billion Muslims around the world,[5] it is also one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[7]

Aramaic

Aramaic was the native language of the Aramaeans and became the lingua franca of the Assyrian Empire and the western provinces of the Persian Empire, and was adopted by conquered peoples such as the Hebrews. A dialect of Old Aramaic developed into the literary language Syriac. The Syriacs, such as the Syriac-Aramaean, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, continued the use of Aramaic which ultimately evolved into the Neo-Aramaic dialects of the Middle East.

Azeri

Azeri served as a lingua franca in Transcaucasia (except the Black Sea coast), Southern Daghestan, Eastern Anatolia,[8][9] and Iranian Azerbaijan from the 16th century to the early 20th century. Its role has now been taken over by Russian in the North Caucasus, and by the official languages of the various independent states of the South Caucasus.[10][11]

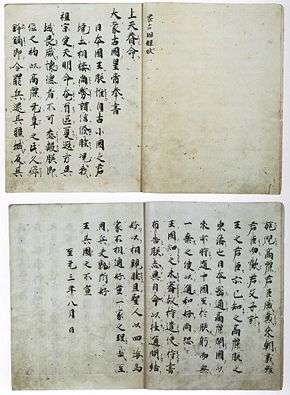

Chinese

Until the early 20th century, Classical Chinese served as both the written lingua franca and the diplomatic language in Far East Asia including China, Mongolia, Korea, Japan, the Ryūkyū Kingdom, and Vietnam. In the early 20th century, vernacular written Chinese replaced Classical Chinese within China as both the written and spoken lingua franca for speakers of different Chinese dialects, and because of the falling power and cultural influence of China in East Asia, English has since replaced Classical Chinese as the lingua franca in East Asia.

Hebrew

Throughout the centuries of Jewish exile, Hebrew has served the Jewish people as a lingua franca; allowing Jews from different areas of the world to communicate effectively with one another. This was particularly valuable for cross-culture mercantile trading that became one of the default occupations held by Jews in exilic times. Without the need for translators, documents could easily be written up to convey significant legal trade information. Among early Zionists, a newly reconstructed form of Hebrew served as a common language between Jews from nations as diverse as Poland and Yemen. In modern Israel, Hebrew is the commonly accepted language of administration and trade, even among Israeli-Arabs whose mother-tongue remains Arabic.

Hindustani

Hindustani, or Hindi–Urdu, is commonly spoken in India and Pakistan. It encompasses two standardized registers in the form of the official languages of Hindi and Urdu, as well as several nonstandard dialects. Hindi is one of the official languages of India, and Urdu is the national language and lingua franca of Pakistan. Urdu is also an official language in India. However, whilst the words and much of the speaking may sound similar, many literary differences are present, and Urdu is written in Nastaliq script while Hindi is written in the Devanagari script.

Hindi is also a lingua franca in Nepal. In the Terai i.e. floodplain districts of Nepal (along the Indian border), Hindi is a dominant language, though the people's mother tongues are typically Avadhi, Maithili, or Bhojpuri.

Malay-Indonesian

In the 15th century, during the Malacca Sultanate, Malay was used as a lingua franca in Maritime Southeast Asia, by locals, and traders and artisans that stopped at Malacca via the Straits of Malacca. Malay was also presumably used as a language of trade among the elites and artisans around the islands of modern-day Philippines. Dutch scholar, Francois Valentijn (1666–1727) described the use of Malay in the region as being equivalent to the contemporary use of Latin and French in Europe.[12]

Nowadays, Malay is used mostly in Malaysia (officially called Bahasa Malaysia) and Brunei, and to a lesser extent in Singapore and parts of Sumatra. One of Singapore's four official languages, the Malay language or 'Bahasa Melayu' was the lingua franca for Malays in Singapore prior to the introduction of English as a working and instructional language, and remains so for the elder generation.

Indonesian, a language based on traditional Malay and with which it is mutually intelligible, but also influenced by various languages such as Dutch, Sanskrit, Javanese, Arabic, and Portuguese, serves as a lingua franca throughout Indonesia and East Timor (where it is considered a working language), areas that are home to over 700 indigenous languages.

Persian

Persian became the second lingua franca of the Islamic world, in particular of the eastern regions.[13] Besides serving as the state and administrative language in many Islamic dynasties, some of which included Samanids, Ghurids, Ghaznavids, Ilkhanids, Seljuqids, Moguls and early Ottomans, Persian cultural and political forms, and often the Persian language, were used by the cultural elites from the Balkans to India.[14] For example, Persian was the only oriental language known and used by Marco Polo at the Court of Kublai Khan and in his journeys through China.[15] Arnold Joseph Toynbee's assessment of the role of the Persian language is worth quoting in more detail:

In the Iranic world, before it began to succumb to the process of Westernization, the New Persian language, which had been fashioned into literary form in mighty works of art ... gained a currency as a lingua franca; and at its widest, about the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries of the Christian Era, its range in this role extended, without a break, across the face of South-Eastern Europe and South-Western Asia.[16]

Persian remains the lingua franca in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan and was the lingua franca of North India before the British conquest. It is still understood by many in South Asia, mainly Southwestern Pakistan.

Sogdian

The lingua franca was Sogdian in Central Asia.[17]

Tagalog

Tagalog was declared the official language by the first constitution in the Philippines, the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.[18] Native Tagalog speakers continue to make up one of the country's largest linguistic and cultural groups, numbering an estimated 14 million. The Filipino language, which is standardised register of Tagalog, is taught in schools throughout the Philippines and is an official language of education and business along with English.[19]

Due to the large number of Languages of the Philippines, the designation of Tagalog (as 'Filipino') as 'national' in character is often disputed, as Cebuano and Ilocano are among several tongues that have comparatively large numbers of speakers, and are themselves used as linguae francae. See also Imperial Manila.

Europe

English

English is the current lingua franca of international business, education, science, technology, diplomacy, entertainment, radio, seafaring, and aviation. After World War II, it has gradually replaced French as the lingua franca of international diplomacy.[20] The rise of English in diplomacy began in 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles was written in English as well as in French, the dominant language used in diplomacy until that time. The widespread use of English was further advanced by the prominent international role played by English-speaking nations (the United States and the Commonwealth of Nations) in the aftermath of World War II, particularly in the establishment and organization of the United Nations. English is one of the six official languages of the United Nations (the other five being French, Arabic, Chinese, Russian and Spanish). The seating and roll-call order in sessions of the United Nations and its subsidiary and affiliated organizations is determined by alphabetical order of the English names of the countries.

When the United Kingdom became a colonial power, English served as the lingua franca of the colonies of the British Empire. In the post-colonial period, some of the newly created nations which had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as an official language to avoid the political difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous language above the others. The British Empire established the use of English in regions around the world such as North America, India, Africa, Australia and New Zealand, so that by the late 19th century its reach was truly global,[21] and in the latter half of the 20th century, widespread international use of English was much reinforced by the global economic, financial, scientific, military, and cultural pre-eminence of the English-speaking countries and especially the U.S. Today, more than half of all scientific journals are published in English, while in France, almost one-third of all natural science research appears in English,[22] lending support to English being the lingua franca of science and technology. English is also the lingua franca of international air traffic control and seafaring communications.

French

French was the language of diplomacy from the 17th century until the mid-20th century,[20] and is still a working language of some international institutions. In the international sporting world French is still the lingua franca as the International Olympic Committee and FIFA use French. It was also the lingua franca of European literature in the 18th century. French is still seen on documents ranging from passports to airmail letters. Until the accession of the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark in 1973, French and German were the official working languages of the European Economic Community.

French is spoken by educated people in cosmopolitan cities of the Middle East and North Africa and remains so in the former French colonies of the Maghreb, where French is particularly important in economic capitals such as Algiers, Casablanca and Tunis. Until the outbreak of the civil war in Lebanon, French was spoken by the upper-class Christian population. French is still a lingua franca in most Western and Central African countries and an official language of many, a remnant of French and Belgian colonialism. These African countries and others are members of the Francophonie. French is the official language of the Universal Postal Union, with English added as a working language in 1994.[23]

German

German served as a lingua franca in large portions of Europe for centuries, mainly the Holy Roman Empire, but was also wider used due to organisations like the Hanseatic League (see Low German).

Previously one of the official languages of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, German remained an important second language in much of Central and Eastern Europe long after the dissolution of that empire after World War I. Today, it is still the most common second language in some of the countries in the region (e.g. in Slovenia (45% of the pop.), Croatia (34%),[24] the Czech Republic (31%) and Slovakia (28%). In others, it is also known by significant numbers of the population (in Poland by 18%, in Hungary by 16%).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, German was a prerequisite language for scientists. Despite the anti-German sentiment after World War II, it remains a widespread language among scientists.

Greek and Latin

During the time of the Hellenistic civilization and Roman Empire, the lingua francas were Koine Greek and Latin. During the Middle Ages, the lingua franca was Greek in the parts of Europe, Middle East and Northern Africa where the Byzantine Empire held hegemony, and Latin was primarily used in the rest of Europe. Latin, for a significant portion of the expansion of the Roman Catholic Church, was the universal language of prayer and worship. During the Second Vatican Council, Catholic liturgy changed to local languages, although Latin remains the official language of the Vatican. Latin was used as the language of scholars in Europe until the early 19th century in most subjects. For instance, Christopher Simpson's "Chelys or The Division viol" on how to improvise on the viol (viola da gamba) was published in 1665 in a multilingual edition in Latin and English, to make the material accessible for the wider European music community. Another example is the Danish-Norwegian writer Ludvig Holberg, who published his book "Nicolai Klimii iter subterraneum" in 1741 about an ideal society "Potu" ("Utop" backwards) with equality between the genders and an egalitarian structure, in Latin in Germany to avoid Danish censorship and to reach a greater audience. Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica was published in Latin in 1687: the first English translation did not appear until 1729. In subjects like medicine and theology Latin has been a subject of study until the present day in most European universities, despite declining use in recent years.

Italian

The Mediterranean Lingua Franca was largely based on Italian and Provençal. This language was spoken from the 11th to 19th centuries around the Mediterranean basin, particularly in the European commercial empires of Italian cities (Genoa, Venice, Florence, Milan, Pisa, Siena) and in trading ports located throughout the eastern Mediterranean rim.[25]

During the Renaissance, standard Italian was spoken as a language of culture in the main royal courts of Europe, and among intellectuals. This lasted from the 14th century to the end of the 16th, when French replaced Italian as the usual lingua franca in northern Europe. On the other hand, Italian musical terms, in particular dynamic and tempo notations, have continued in use to the present day, especially for classical music, in music revues and program notes as well as in printed scores. Italian is considered the language of Opera.[26]

In the Catholic ecclesiastic hierarchy, Italian is known by a large part of members and is used in substitution of Latin in most official documents as well. The presence of Italian as the official language in Vatican City indicates its use not only in the seat in Rome, but also anywhere in the world where an episcopal seat is present.

Italian served as the official lingua franca in Italian North Africa (present-day Libya, consisting of the colonies of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fazzan) and in Italian East Africa (consisting of the present-day countries of the Horn of Africa: Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia).[27]

Low German

From about 1200 to 1600, Middle Low German was the language of the Hanseatic League which was present in most Northern European seaports, even London. It resulted in numerous Low German words being borrowed into Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. After the Middle Ages, modern High German and Dutch began to displace Low German, and it has now been reduced to many regional dialects, although they are still largely mutually intelligible. In recent years, the language has seen a resurgence in public interest, and it is increasingly being used as a mode of communication between speakers of (northern) German and (eastern) Dutch nationality.

Polish

Polish was a lingua franca in areas of Eastern Europe, especially regions that belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish was for several centuries the main language spoken by the ruling classes in Lithuania and Ukraine, and the modern state of Belarus.[28] After the Partitions of Poland and the incorporation of most of the Polish areas into the Russian Empire as Congress Poland, the Russian language almost completely supplanted Polish.

Portuguese

Portuguese served as lingua franca in the Portuguese Empire, Africa, South America and Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries. When the Portuguese started exploring the seas of Africa, America, Asia and Oceania, they tried to communicate with the natives by mixing a Portuguese-influenced version of Lingua Franca with the local languages. When English or French ships came to compete with the Portuguese, the crews tried to learn this "broken Portuguese". Through a process of change the Lingua Franca and Portuguese lexicon was replaced with the languages of the people in contact.

Portuguese remains an important lingua franca in Africa (PALOP), East Timor, Goa, and to a certain extent in Macau where it is recognized as an official language alongside Chinese though in practice not commonly spoken.

Russian

Russian is in use and widely understood in Northern and Central Asia, areas formerly part of the Soviet Union or bloc, and may be understood by older people in Central and Eastern Europe, formerly part of the Warsaw Pact. It remains the lingua franca in the Commonwealth of Independent States (the former Soviet Union minus the more Western Baltic states, where English and German are preferred). Russian is also one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[7]

Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian is a lingua franca in several of the territories of the former Yugoslavia, that is, modern Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia. In those four countries it is the main native language, and is also spoken by ethnic minorities. For example, a Hungarian from Vojvodina and an Italian from Istria might use it as a shared second language. Most people in Slovenia and Macedonia can understand or speak Serbo-Croatian as well. It is a pluricentric language and is commonly referred to as Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian or Montenegrin depending on the background of the speaker.

Spanish

With the growth of the Spanish Empire, Spanish became established in the Americas, as well as in parts of Africa, Asia and Oceania. It became the language of global trade until Napoleonic Wars and the breakup of the Spanish Empire at the beginning of the 19th century. Spanish was used as a lingua franca throughout the former Spanish Colonial Empire, including territory in present-day U.S., but particularly in present-day Mexico, Spanish Caribbean, Central and South America, and it's still the lingua franca within Hispanic America.

At present it is the second most used language in international trade, and the third most used in politics, diplomacy and culture after English and French.[29]

Yiddish

Yiddish originated in the Ashkenazi culture that developed from about the 10th century in the Rhineland and then spread to central and eastern Europe and eventually to other continents. For a significant portion of its history, Yiddish was the primary spoken language of the Ashkenazi Jews. Eastern Yiddish, three dialects of which are still spoken today, includes a significant but varying percentage of words from Slavic, Romanian and other local languages.

On the eve of World War II, there were 11 to 13 million Yiddish speakers, for many of whom Yiddish was not the primary language. The Holocaust, however, led to a dramatic, sudden decline in the use of Yiddish, as the extensive Jewish communities, both secular and religious, that used Yiddish in their day-to-day life were largely destroyed. Although millions of Yiddish speakers survived the war, further assimilation in countries such as the United States and the Soviet Union, along with the strictly Hebrew monolingual stance of the Zionist movement, led to a decline in the use of Yiddish. However, the number of speakers within the widely dispersed Orthodox (mainly Hasidic) communities is now increasing. It is a home language in most Hasidic communities, where it is the first language learned in childhood, used in schools, and in many social settings.

In the United States, as well as South America, the Yiddish language bonded Jews from many countries. Most of the Jewish immigrants to the New York metropolitan area during the years of Ellis Island considered Yiddish their native language. Later, Yiddish was no longer the primary language for the majority of the remaining speakers and often served as lingua franca for the Jewish immigrants who did not know each other's primary language, particularly following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yiddish was also the language in which second generation immigrants often continued to communicate with their relatives who remained in Europe or moved to Israel, with English, Spanish or Portuguese being primary language of the first and Russian, Romanian, or Hebrew that of the second.

Pre-Columbian North America

Chinook Jargon

Chinook Jargon was originally constructed from a great variety of Amerind words of the Pacific Northwest, arising as an intra-indigenous contact language in a region marked by divisive geography and intense linguistic diversity. The participating peoples came from a number of very distinct language families, speaking dozens of individual languages.

After European contact, the Jargon also acquired English and French loans, as well as words brought by other European, Asian, and Polynesian groups. Some individuals from all these groups soon adopted the Jargon as a highly efficient and accessible form of communication. This use continued in some business sectors well into the 20th century and some of its words continue to feature in company and organization names as well as in the regional toponymy.

In the Diocese of Kamloops, British Columbia, hundreds of speakers also learned to read and write the Jargon using the Duployan shorthand via the publication Kamloops Wawa. As a result, the Jargon also had the beginnings of its own literature, mostly translated scripture and classical works, and some local and episcopal news, community gossip and events, and diaries. Novelist and early Native American activist, Marah Ellis Ryan (1860?–1934) used Chinook words and phrases in her writing.

According to Nard Jones, Chinook Jargon was still in use in Seattle until roughly the eve of World War II, especially among the members of the Arctic Club, making Seattle the last city where the language was widely used. Writing in 1972, he remarked that at that later date "Only a few can speak it fully, men of ninety or a hundred years old, like Henry Broderick, the realtor, and Joshua Green, the banker."

Jones estimates that in pioneer times there were about 100,000 speakers of Chinook Jargon.

Nahuatl

Classical Nahuatl was the lingua franca of the Aztec Empire in Mesoamerica prior to the Spanish invasion in the 16th century. An extensive corpus of the language as spoken exists. Like Latin and Hebrew (prior to the founding of modern Israel), Classical Nahuatl was more of a sociolect spoken among the elites (poets, priests, traders, teachers, bureaucrats) than a language spoken in any common family household.

After the Spanish conquest, Nahuatl remained the lingua franca of New Spain. Spanish friars matched the language to a Latin alphabet, and schools were established to teach Nahuatl to Spanish priests, diplomats, judges, and political leaders. In 1570, Nahuatl was made the official language of New Spain, and it became the lingua franca throughout Spanish North America, used in trade and the courts. During the prolonged Spanish conquest of Guatemala Spain's native allies, mostly from Tlaxcala and Cholula, spread Nahuatl to Maya areas where it was not spoken prior to the arrival of the Spanish, resulting in Nahuatl placenames across Guatemala which persist up to the present.[30] In 1696, the official use of any language other than Spanish was banned throughout the empire. Especially since Mexican independence, the use of Nahuatl has dwindled.

Occaneechi

Prior to European colonization, the Occaneechi dialect of the Tutelo language served as a lingua franca in the land that would become the state of Virginia. Tutelo was a Siouan language. But Robert Beverley, Jr. observed that the Tuscarora, who spoke an Iroquoian language, and the Powhatan, who spoke an Algonquian language, both used Occaneechi in religious ceremonies, much like modern Christian communities use Latin.[31] Beverley also noted that the Occaneechi language was used by all native nations of Virginia as a trade language.

After European colonists introduced devastating infectious diseases, all native languages of Virginia began to decline. All dialects of Tutelo, including Occaneechi, became extinct by the end of the 20th century. However, there is considerable documentation of the language by numerous linguists, and interest among modern Tutelo people in reviving the language.[32]

South America

Portuguese and Spanish started to grow as lingua francas in the region in since the conquests of the 16th century. In the Case of Spanish this process was not even and as the Spanish used the structure of Inca Empire to consolidate their rule Quechua remained the lingua franca of large parts of what is now Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. Quechua importance as a language for trade and dealing with Spanish-approved indigenous authorities (curaca) made the language expand even after the Spanish conquest. It was not until the rebellion of Túpac Amaru II that the Spanish authorities changed to a policy of Hispanization that was continued by the republican states of Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia. Quechua also lost influence to Spanish as the commerce circuits grew to integrate other parts of the Spanish Empire where Quechua was unknown, for example in the Rio de la Plata.

Quechua

Also known as Runa Simi, as the Inca empire rose to prominence in South America, this imperial language became the most widely spoken language in the western regions of the continent. Even among tribes that were not absorbed by the empire Quechua still became an important language for trade because of the empire's influence. Even after the Spanish conquest of the Andes, Quechua for a long time was the most common language, and was promoted by the Spanish colonial authorities in the first centuries of colonization. Today it is still widely spoken although it has given way to Spanish as the more common lingua franca. It is spoken by some 10 million people through much of South America (mostly in Peru, south-western and central Bolivia, southern Colombia and Ecuador, north-western Argentina and northern Chile).

Mapudungun

Mapudungun was for a long time used as lingua franca in large portions of Chile and Argentine Patagonia. Adoption of Spanish was in Chile a slow process and by the 19th century the unconquered Indians of Araucanía had spread their language across the Andes during a process called Araucanization. Pehuenches were among the first non-Mapuche tribes to adopt the language. The increasing commerce over the Andes and the migration of Mapuches into the Patagonian plains contributed to the adoption of Mapudungun by other tribes of a more simple material culture. Even in Chiloé Archipelago Spaniards and mestizos adopted a dialect of Mapudungun as their main language.

Tupi

The Old Tupi language served as the lingua franca of Brazil among speakers of the various indigenous languages, mainly in the coastal regions. Tupi as a lingua franca, and as recorded in colonial books, was in fact a creation of the Portuguese, who assembled it from the similarities between the coastal indigenous Tupi–Guarani languages. The language served the Jesuit priests as a way to teach natives, and it was widely spoken by Europeans. It was the predominant language spoken in Brazil until 1758, when the Jesuits were expelled from Brazil by the Portuguese government and the use and teaching of Tupi was banned.[33] Since then, Tupi as Lingua Franca was quickly replaced by Portuguese, although various Tupi–Guarani languages are still spoken by small native groups in Brazil.

Pidgins and creoles

Various pidgin languages have been used in many locations and times as a common trade speech. They can be based on English, French, Chinese, or indeed any other language. A pidgin is defined by its use as a lingua franca, between populations speaking other mother tongues. When a pidgin becomes a population's first language, then it is called a creole language.

Guinea-Bissau Creole

Guinea-Bissau Creole is a Portuguese Creole used as a lingua franca of Guinea-Bissau and Casamance, Senegal among people of different ethnic groups. It is also the mother tongue of many people in Guinea-Bissau.

Tok Pisin

Tok Pisin is widely spoken in Papua New Guinea as a lingua franca. It developed as an Australian English-based creole with influences from local languages and to a smaller extent German or Unserdeutsch and Portuguese. Tok Pisin originated as a pidgin in the 19th century, hence the name 'Tok Pisin' from 'Talk Pidgin', but has now evolved into a modern language.

Also called Pidgin English, this Lingua Franca is also spoken in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. The versions of Pidgin vary between PNG, the Solomons and Vanuatu, but all Pidgin speakers from these countries are able to communicate and often understand each other's language variations.

See also

References

- ↑ "World Factbook - Ethiopia". CIA. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ FANAGALO – © J. Olivier (2009) – SA Languages.

- ↑ Bokamba, Eyamba G. (2009). "The spread of Lingala as a lingua franca in the Congo Basin". In McLaughlin, Fiona. The Languages of Urban Africa. London, New York: Continuum. pp. 50–70. ISBN 978-1-84706-116-4. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ↑ "Arabic Alphabet". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- 1 2 "United Nations Arabic Language Programme". United Nations. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ↑ "Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People". Microsoft Encarta 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- 1 2 "Department for General Assembly and Conference Management – What are the official languages of the United Nations?". United Nations. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ↑ Pieter Muysken, "Introduction: Conceptual and methodological issues in areal linguistics", in Pieter Muysken, From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics, 2008 ISBN 90-272-3100-1, p. 30–31

- ↑ Viacheslav A. Chirikba, "The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund" in Muysken, p. 74

- ↑ Nasledie Chingiskhana by Nikolai Trubetzkoy. Agraf, 1999; p. 478

- ↑ J. N. Postgate. Languages of Iraq. British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2007; ISBN 0-903472-21-X; p. 164

- ↑ (Malay) Wawasan: Bahasa Melayu Salah Satu Bahasa Utama Dunia, Buku Pelan Tindakan Strategik DBP 2011–2015 (Memartabatkan Bahasa dan Persuratan Melayu). page 10. Terbitan Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP).

- ↑ Dr Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization, HarperCollins,Published 2003

- ↑ Robert Famighetti, The World Almanac and Book of Facts, World Almanac Books, 1998, p. 582

- ↑ John Andrew Boyle, SOME THOUGHTS ON THE SOURCES FOR THE IL-KHANID PERIOD OF PERSIAN HISTORY, in Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies, British Institute of Persian Studies, vol. 12 (1974), p. 175

- ↑ Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History,V, pp. 514–15

- ↑ Reuel R. Hanks (2010). Global Security Watch--Central Asia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-313-35422-9.

- ↑ 1897 Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Article VIII, Filipiniana.net, retrieved 2008-01-16

- ↑ http://www.alsintl.com/resources/languages/Tagalog/

- 1 2 Otte, T.G. (1 September 2010). "H-Diplo Review of Sir Ivor Roberts, ed. Satow's Guide to Diplomatic Practice, 6th edition" (PDF). H-Diplo: 5.

One of the striking external changes in diplomatic practice over the past three decades is the extent to which English has now become indisputably the lingua franca of international diplomacy. A comparison of Satow V and VI quickly establishes the fact. It is remarkable how many passages in the Gore-Booth edition of 1979 are still in French. This has been swept away by the tides of recent history ...

- ↑ "Lecture 7: World-Wide English". EHistLing. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ↑ Reinhold Wagnleitner, "Coca-colonization and the Cold War: the cultural mission of the United States in Austria after the Second World War", p. 162

- ↑ "The UPU: Languages". Universal Postal Union. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ↑ "Europeans and their languages – European commission special barometer FEB2006" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ Henry Romanos Kahane. The Lingua Franca in the Levant (Turkish Nautical Terms of Italian and Greek Origin)

- ↑ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=15040264

- ↑ Lingua Franca (in Italian)

- ↑ Barbour, Stephen; Cathie Carmichael (2000). Language and Nationalism in Europe. Oxford UP. p. 194. ISBN 0-19-925085-5.

- ↑ "¿Por qué los brasileños deben aprender español?" – Copyright 2003 Quaderns Digitals Todos los derechos reservados ISSN 1575-9393.

- ↑ http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/beverley/beverley.html

- ↑ http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2005/06/08/tutelo-language-revitalized-96387

- ↑ "Abá nhe'enga oîebyr – Tradução: a língua dos índios está de volta", by Suzel Tunes essay in Portuguese.