Lynne Stewart

| Lynne Stewart | |

|---|---|

|

Lynne Stewart | |

| Born |

Lynne Irene Feltham October 8, 1939 Brooklyn, New York, United States |

| Education | Rutgers School of Law–Newark |

| Occupation | Defense attorney |

| Spouse(s) | Ralph Poynter |

| Children | 1 |

Lynne Irene Stewart (born October 8, 1939) is an American former attorney who was known for representing controversial, poor, and often unpopular defendants. She was convicted on charges of conspiracy and providing material support to terrorists in 2005,[1] and sentenced to 28 months in prison. Her felony conviction led to her being automatically disbarred. She was convicted of helping pass messages from her client, Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, an Egyptian cleric convicted of planning terror attacks, to his followers in al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, an organization designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization by the United States Secretary of State.

She was re-sentenced on July 15, 2010, to 10 years in prison in light of her perjury at trial.[2] She served her sentence at the Federal Medical Center, Carswell, a federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas.[3]

Stewart was released from prison on December 31, 2013 on a compassionate release order because of her terminal breast cancer diagnosis.[4][5][6]

Early life and education

Stewart was born in Brooklyn, New York, the daughter of Irene and John Feltham. Her mother was of German and Swedish descent, while her father had English and Irish ancestry. She grew up in Bellerose, Queens and graduated from Martin Van Buren High School in 1957.[7][8] She attended Hope College in Holland, Michigan but left without a degree. Stewart graduated from Wagner College on Staten Island with a B.A. in political science in 1961.[7][9][10] She earned a Juris Doctor from Rutgers School of Law–Newark in Newark, New Jersey in 1975. She was admitted to practice law in New York in 1977.[11]

Stewart believes that violence is at times needed to correct the injustices of capitalism. She states that she doesn't "believe in anarchistic violence but in directed violence," with directed violence being that which is "directed at the institutions which perpetuate capitalism, racism and sexism, and at the people who are the appointed guardians of those institutions, and accompanied by popular support."[12]

Legal career

Stewart was admitted to the New York State Bar on January 31, 1977[13] and for much of her career as a lawyer, Stewart represented a number of economically disadvantaged clients as well as more high-profile cases. Stewart is a self-described "movement lawyer"[14] who took a wider interest in promoting the general political interests of those she represented, rather than only dealing with the specific charges against them.[15] Stewart defended Weather Underground member David Gilbert, who was found guilty for his role in the 1981 Brinks armored car robbery in which two police officers and a security guard were murdered.[16]

In 1991, Stewart was subpoenaed to explain alternative fee arrangements with a gang member whom she had been defending on a drug trafficking charge. Stewart refused the subpoena and eventually pleaded guilty to second degree criminal contempt, a misdemeanor charge that would not result in her disbarment.[7][17]

Another high-profile client was former Black Panther member Willie Holder who hijacked Western Airlines Flight 701 on June 2, 1972, he claimed to have a bomb and demanded the release of murderer Angela Davis and $500,000.[18]

Along with William Kunstler, Stewart represented Larry Davis, who had been charged with the attempted murder of nine NYPD officers during a shootout, as well as the murder of four Bronx drug dealers. Stewart and Kunstler secured Davis an acquittal on the more serious murder and attempted murder charges, but Davis was found guilty on a lesser felony weapon possession charge.[19] After the trial, Stewart ended her relationship with Kunstler, feeling marginalized by Kunstler hogging the publicity of the case and not giving her due credit. Even Davis believed that Stewart was more instrumental in his acquittal, stating that "everyone thinks Kunstler beat the case. Lynne Stewart beat the case."[20]

Another high-profile client of Stewart's was Sammy "the Bull" Gravano whom she unsuccessfully defended on ecstasy trafficking charges.[21]

Stewart says that all her high-profile clients share the distinction of being revolutionaries against unjust systems or people whose cases expose those injustices.[16] However, unlike most movement lawyers who found communications with prosecuting attorneys to be repugnant, former assistant US Attorney Andrew C. McCarthy, found Stewart to be "eminently reasonable and practical" and commented that "when she gave her word on something, she honored it — she never acted as if she thought one was at liberty to be false when dealing with the enemy."[22]

Abdel-Rahman case

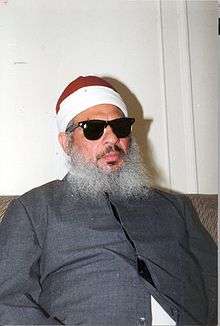

After the first World Trade Center bombing, the FBI began to investigate Omar Abdel-Rahman. The FBI recorded Rahman issuing a fatwa that encouraged acts of violence against US civilian targets, particularly in the New York and New Jersey metropolitan area. Rahman was arrested on 24 June 1993.[23] The targets were the United Nations Headquarters, the Lincoln Tunnel, the Holland Tunnel, the George Washington Bridge, and the FBI's main New York office at the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building.[24] There were also plans to bomb Jewish targets in the city as well as assassinating U.S. Senator Al D'Amato and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak.[25]

In November 1994, former Johnson administration attorney general Ramsey Clark met with Stewart and asked her to take Rahman on as a client after Rahman dismissed his court-appointed lawyer and his other lawyers, William Kunstler and Ron Kuby, were taken off the case for conflict of interest. Stewart was reluctant at first, but Clark convinced her to take the case, arguing that otherwise "the Arab world would feel betrayed by their friends on the American left."[15] Interviewed by the Washington Post about her embrace of Rahman's case, she said, "my own political sense tells me that the only hope for change in Egypt is the fundamentalist movement."[26] Kuby, who had represented Rahman earlier, disagreed with Stewart's characterization, stating, "I love Lynne, but no one in the world could fairly posit the sheikh as a progressive or liberal on any issue." Stewart contended that she understood fundamentalists because attorney general "John Ashcroft is one."[26]

During Rahman's trial, she argued to the jury that Rahman had been framed for his political and religious teachings and not, as the prosecution alleged, for conspiring in any violent acts against the United States.[27] Rahman was convicted of seditious conspiracy on October 1, 1995, and in 1996 he was sentenced to life in prison.[28] Stewart reportedly wept when the jury announced its decision.[15]

Violation of "Special Administrative Measures"

As part of Stewart’s defense of Rahman, and her serving for several years on post-conviction issues, she was subject to modified "special administrative measures" which govern communications between suspects and their legal counsel. Stewart had accepted the condition that, in order to be allowed to meet with Abdel Rahman in prison, she would not "use [their] meetings, correspondence, or phone calls with Abdel Rahman to pass messages between third parties (including, but not limited to, the media) and Abdel Rahman".[29] The special administrative measures, or SAMs, were modified in the wake of the September 11th attacks and were designed to prevent communications that could endanger US national security or lead to acts of violence and terrorism.[30]

According to a federal grand jury indictment, Stewart along with interpreter Mohamed Yousry, an adjunct professor in Middle East studies at York College CUNY, and postal clerk Ahmed Sattar passed messages between Rahman and his supporters in violation of the SAM,[31] thereby conspiring to defraud the United States in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 371. The indictment also charged Stewart with violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2339A and 18 U.S.C. § 2, and making false statements (18 U.S.C. § 1001), and Ahmed Sattar with being an active Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya leader who served as a vital link between Rahman and the group’s members. Stewart was accused in the indictment of passing Rahman's blessing for a resumption of terrorist operations to al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya members in Egypt after they inquired whether they should continue to honor a ceasefire agreement with the Egyptian government.[31] According to video surveillance of Rahman’s cell Stewart, Yousry and Rahman had been tricking the correctional officers into believing that Stewart and Rahman were having a routine conversation relating to his case, when Rahman was dictating statements to Yousry with Stewart joking that she should get an award for acting.[15][32]

Stewart said that the dispute was over one communication on behalf of her client to his supporters via a Reuters article, followed by a clarification after it appeared to have been misinterpreted. The clarification said: "I [Omar Abdel-Rahman] am not withdrawing my support of the cease-fire, I am merely questioning it and I am urging you, who are on the ground there to discuss it and to include everyone in your discussions as we always have done."[33][34]

The material-support charges were dismissed in the summer of 2003, but in November 2003, Stewart was re-indicted[35] on charges of obstruction of justice and conspiracy to provide material support to terrorism. She was convicted on these charges.

According to Judge John G. Koeltl, in denying Stewart's motion to reject the verdict as unfounded,

A rational jury could have inferred that, by relaying a statement withdrawing support for a cessation of violence by an influential, pro-violence leader of a terrorist group, Stewart knew that she was providing support to those within the IG (Islamic Group) who sought to return to violence—who the jury could have found were participants in the Count Two conspiracy, particularly Taha.[34]

Michael Tigar, her attorney, stated that "this case really is a threat to all the lawyers who are out there attempting to represent people that face these terrible consequences."[33] Supporters of Stewart alleged that the government charged her for her speech in defending the rights of her client. They believed that Stewart's efforts to release communications from her client were part of an appropriate defense method to gain public awareness and support. They also expressed alarm that wiretaps and hidden cameras authorized by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act were used by the government to gather evidence against her, which they called a violation of attorney–client privilege. George Soros' Open Society Institute also donated $20,000 to Stewart's legal defense fund in 2002.[36] Commenting on her case, human rights organization Front Line states that it "has had a chilling effect on human rights defenders who stand between government agencies and potential victims of abuses."[37]

Conviction

On February 10, 2005, following a nine-month trial and 13 days of jury deliberations, Stewart was found guilty of conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government (18 U.S.C. § 371), providing material support to terrorists (18 U.S.C. § 2339A and 18 U.S.C. § 2) and conspiring to conceal it (18 U.S.C. § 371), and making false statements (18 U.S.C. § 1001). Co-defendants Mohamed Yousry and Ahmed Sattar were found guilty as charged.[38][39] Her conviction meant automatic disbarment.

Stewart remained free on bail pending the results of her appeal.[40]

Sentencing submissions

The original sentencing was to be in July 2005, but Stewart's defense team had repeatedly asked for and received numerous adjournments because she was receiving treatment for breast cancer. The defense team also argued that Stewart's age, problematic general health and cancer history could well mean that she would be in prison for the rest of her life if she were sentenced to serve several years.

In a letter to the court dated September 26, 2006, Stewart stated that her actions were consistent with how she had always represented her clients but that she had failed to recognize the difference in a post-2001 United States and that, in hindsight, should have been more careful to avoid misinterpretation. Claiming that persons with 'other agendas' had misinterpreted her actions, she said: "I inadvertently allowed those with other agendas to corrupt the most precious and inviolate basis of our profession – the attorney-client relationship.".[41]

According to The New York Times, Stewart "acknowledged ... that she knowingly violated prison rules".[42] She requested that the Court exercise the sentencing discretion given judges by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in U.S. v. Booker, and impose a non-custodial sentence. The prosecution requested that the Court impose the maximum statutory penalty, saying, "We hope that this sentence of 30 years will not only punish Stewart for her actions, but serve as a deterrent for other lawyers who believe that they are above the rules and regulations of penal institutions or otherwise try to skirt the laws of this country."[43]

Judge Koeltl refused both to impose the 30-year sentence proposed by the prosecution or to waive jail time entirely as Stewart had requested. He stated that while over her long career of representing unpopular clients, Stewart had "performed a public service, not only to her clients, but to the nation", her conduct was "criminal" in this case.[44]

On October 16, 2006, Judge Koeltl sentenced Stewart to 28 months in prison. Yousry and Sattar were sentenced to 20 months and 28 years, respectively. Yousry was released in 2011. Sattar is serving his sentence at the Federal Supermax prison near Florence, Colorado.[45]

Re-sentencing; 10 years

In response to Stewart's appeal, a Second Circuit Court of Appeals panel affirmed the convictions on November 17, 2009 and ordered the district court to revoke Stewart's bail immediately and take her into custody.

The appeals court went even further: it remanded the case for re-sentencing in light of her possible perjury at her trial, and other factors the court considered had not been properly weighed against her by the sentencing judge.[46]

On November 19, 2009, Stewart surrendered to U.S. Marshals in New York City to begin serving the original 28-month sentence as prisoner #53504-054. Two months later, in January 2010, the full Second Circuit bench, in a split decision, declined to reconsider its panel's affirmance and re-sentencing directive. On July 15, 2010, Stewart was re-sentenced by Judge Koeltl to 10 years in prison, taking into consideration what he concluded were false statements she made under oath at her trial and other factors as directed by the appellate court.[47]

Lawyer Herald Price Fahringer contested the new sentence, bringing the case back to the Court of Appeals. On February 29, 2012, Fahringer presented oral argument based on freedom of speech, arguing that out-of-court comments on a public issue cannot be punished with enhanced imprisonment, suggesting that otherwise "no one will be able to comment after a sentence for fear that the same thing could happen to them."[48] This appeal later failed before a panel of judges, after finding no violations of free speech.[49] Stewart filed a certiorari petition to the United States Supreme Court in February 2013.[50]

Health condition in prison

Stewart's breast cancer returned after she was imprisoned. Scheduled for surgery for other problems the week she was sentenced, Stewart instead had to wait eighteen months for that surgery. In the meantime the cancer metastasized to the point that her attending physician called it the worst case he had ever seen.[51] She received chemotherapy in custody.[50]

On June 25, 2013, Stewart announced that she had received a letter stating that Federal Bureau of Prisons Director Charles Samuels had denied her request for compassionate release.[52]

In December 2013, prosecutors wrote a letter to the judge stating that Stewart had 18 months to live. They said she had been diagnosed with anemia, high blood pressure, asthma and Type 2 diabetes.[53]

On December 31, 2013, the denial of Stewart's request for compassionate release was reversed after Stewart's doctor said she had only 18 months to live. The Federal Bureau of Prisons and the office of U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York filed a motion asking the judge in Stewart's case for a compassionate release.[54] Judge Koeltl granted the motion, and on December 31, 2013, Stewart was released from prison.

Post Release

In September, 2016, Stewart was quoted on the assassinations of police in Dallas and Baton Rouge. “They are not brazen, crazed, you know, insane killers,” . . .“They are avenging deaths that are never and have never been avenged since the ’60s and ’70s.” [55]

Personal life

Stewart has a son, Geoffrey S. Stewart, also a lawyer, who lives in Brooklyn, New York.[54][56][57]

Stewart is married to Ralph Poynter.[53][58]

References

- ↑ "Lynne Stewart still combative after terror verdict". Thevillager.com. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Staff, Post (2010-07-15). "Attorney who helped terrorist gets 10 years in prison | New York Post". Nypost.com. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Inmate 53504-054

- ↑ "NY judge orders 'compassionate release' of terror lawyer Lynne Stewart". Fox News. December 31, 2013.

- ↑ "BREAKING: Lynne Stewart Freed From Prison, Granted "Compassionate Release"". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Ferrigno, Lorenzo (2014-01-01). "Dying defense lawyer Lynne Stewart released from jail". CNN.com. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 3 Goldman, John J. (April 10, 2002). "Accused Lawyer Has a Warm, Tough Side". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Lynne's Bio". Justice for Lynne Stewart. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Court weighs term, meted out in terror case, to disbarred lawyer with Staten Island ties". SILive.com. 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "INDICTED AND DEFIANT / Radical attorney Lynne Stewart stand accused of abetting terrorists. Her response: 'Emphatically not guilty.'". Newsday. 2002-06-02. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "Lawyer Lynne Stewart - New York, NY Attorney". Avvo.com. 2009-03-22. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Joseph Fried. In Muslim Cleric's Trial, a Radical Defender; Left-Leaning Lawyer and Revolutionary Sympathizer Comes Back in the Limelight. NY Times. June 28, 1995

- ↑ "IN RE: Lynne F. STEWART (admitted as Lynne Feltham Stewart) | FindLaw". Caselaw.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "Lynne Stewart's message to Jan. 25 protests | Fight Back!". Fightbacknews.org. 2011-01-25. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Packer, George (2002-09-22). "Left Behind". NYTimes.com. EGYPT. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 Feuer, Alan (2002-04-10). "A NATION CHALLENGED - THE LAWYER - A Persistent Defender, Even in a Mets Cap". NYTimes.com. New York City. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Lawyer And Aides For Cleric Are Charged Radical Attorney's Biggest Fight Yet. NY Daily News. April 10, 2002

- ↑ "The Nation - latimes". Articles.latimes.com. 1986-07-27. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Tomasson, Robert E (1991-03-15). "Larry Davis Convicted in Killing of a Drug Dealer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

Larry Davis, who gained near folk-hero status in some quarters after a shootout with police officers and then beat back three attempts by prosecutors to convict him of murder and attempted murder, was convicted last night of killing a drug dealer in a Bronx robbery.

- ↑ David J. Langum. William M. Kunstler: the most hated lawyer in America. NYU Press. Pg 307

- ↑ Geoff Mulvihill. Mafia Boss Gets 13 Years Behind Bars. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 23, 2005.

- ↑ Archived January 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Sedition – Further Readings". Law.jrank.org. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- ↑ Phil Hirschkorn. "CNN.com - Jury gets embassy bombings case and goes home - May 10, 2001". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Lee, Steven (1993-07-18). "Man In New Jersey Is Charged In Plot To Kill Mubarak - Nytimes.Com". The New York Times. Egypt; New York City. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 "Accused of Aiding Terror Plot, Lawyer Braces for Fight of Her Life". Washingtonpost.com. 2004-06-22. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Joseph Fried. In Muslim Cleric's Trial, a Radical Defender; Left-Leaning Lawyer and Revolutionary Sympathizer Comes Back in the Limelight, NY Times. June 28, 1995

- ↑ "Terrorism in the United States". Fas.org. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- ↑ "Lawyer in Terrorism Trial Is Confronted With Promise". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "Monitoring Attorney-Client Communications of Designated Federal Prisoners : Publications : The Federalist Society". Fed-soc.org. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 "''Department of Justice''". Usdoj.gov. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Patricia Hurtado. ATTORNEY ON TRIAL, 'A secret ... channel', Prosecutors say lawyer for sheik imprisoned in '93 WTC bombing enabled client to communicate with followers who then carried out terrorist acts. Newsday. October 18, 2004

- 1 2 "Convicted Attorney Lynne Stewart: "You Can't Lock Up the Lawyers"". Democracy Now. February 11, 2005. Retrieved October 16, 2006.

- 1 2 UNITED STATES of America v. Ahmed Abdel SATTAR, a/k/a “Abu Omar,” a/k/a “Dr. Ahmed,” Lynne Stewart, and Mohammed Yousry, Defendants. No. S1 02 CR. 395(JGK). October 24, 2005.

- ↑ "''findlaw.com''". News.findlaw.com. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Byron York Soros Funded Stewart Defense; National Review

- ↑ "Human Rights Defender Lynne Stewart". Front Line. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Superseding Indictment: U.S. v. Ahmed Abdel Sattar, Lynne Stewart, and Mohammed Yousry". News.findlaw.com. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Civil rights attorney convicted in terror trial – February 10, 2005". CNN.com. February 14, 2005. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Paul Vitello. Hofstra Polite as Lawyer Guilty in Terror Case Talks on Ethics. New York Times. October 17, 2007

- ↑ "Letter from Stewart to Judge Koeltl" (PDF). Lynnestewart.org. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Preston, Julia (September 29, 2006). "Lawyer in Terror Case Apologizes for Violating Special Prison Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ Larry Neumeister. Lynne Stewart seeks non-prison sentence. Associated Press. July 8, 2006.

- ↑ "US lawyer jailed on terror charge". BBC News. October 16, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Federal Bureau of Prisons". Bop.gov. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Gendar, Alison; Goldsmith, Samuel (November 17, 2009). "Conviction of disbarred lawyer Lynne Stewart upheld for smuggling messages to jailed terrorist". New York: Nydailynews.com. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ↑ Shifrel, Scott; Fanelli, James (July 15, 2010). "Lynn Stewart, 70-year-old radical lawyer, sentenced to 10 years in prison for aiding bomb plotter". Daily News. New York.

- ↑ Hamblett, Mark (March 1, 2012). "Stewart Challenges Resentence, Claims Penalty for Speech". New York Law Journal.

- ↑ Weiser, Benjamin (June 28, 2012). "Lynne Stewart's 10-Year Prison Sentence Is Upheld". New York Times.

- 1 2 Charlotte Silver. "Shocked conscience: the case of Lynne Stewart". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Poynter, Ralph (2013-04-23). "Lynne Stewart cancer metastasis". Letters and Politics (Interview). Interview with Mitch Jeserich. KPFA. Retrieved 2013-05-11.

- ↑ "Ex-Lawyer Convicted In Terror Case Denied Release From Prison". Huffington Post. June 29, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- 1 2 Archived January 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Dying defense lawyer Lynne Stewart released from jail". CNN. January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ http://nypost.com/2016/09/05/disgraced-civil-rights-lawyer-calls-cop-killers-avengers/

- ↑ Preston, Julia (February 12, 2005). "Regretting the Bravado, a Convicted Lawyer Examines Her Options". The New York Times.

- ↑ Weiser, Benjamin (May 20, 2013). "Bin Laden's Son-in-Law Asks to Change Lawyers". The New York Times.

- ↑ Moynihan, Colin (November 20, 2009). "Radical Lawyer Convicted of Aiding Terrorist Is Jailed". The New York Times.

External links

- Justice for Lynne Stewart site

- U.S. v. Sattar (Stewart; Yousry), no. 06-5015-cr (L), (2d Cir. November 17, 2009)

- The conviction of Lynne Stewart and the uncertain future of the right to defend. American Criminal Law Review

- Cheerleaders for Terrorism - a critical view of Lynn Stewart Front Page Magazine

- The Persecution of Lynne Stewart. Chris Hedges, Truthdig. April 21, 2013