Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

| Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Margaret Macdonald 5 November 1864 Tipton, England, United Kingdom |

| Died |

7 January 1933 (aged 67) Chelsea, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Education | Glasgow School of Art |

| Known for | Decorative Arts, Design, Art |

| Movement | Art Nouveau, Glasgow Style, Symbolism |

| Spouse(s) | Charles Rennie Mackintosh |

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (5 November 1864 – 7 January 1933) was a Scottish artist whose design work became one of the defining features of the "Glasgow Style" during the 1890s.

Biography

Born Margaret Macdonald, at Tipton, near Wolverhampton, her father was a colliery manager and engineer. Margaret and her younger sister Frances both attended the Orme Girls' School, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire; their names are recorded in the school register.[1] In the 1881 census Margaret, aged 16, was a visitor at someone else's house on census night and was listed as a scholar.[2] By 1890 the family had settled in Glasgow and Margaret and her sister, Frances Macdonald, enrolled as day students at the Glasgow School of Art studying courses in design.[3] There she worked in a variety of media, including metalwork, embroidery, and textiles.

She began collaborating with her sister Frances, and in the 1890s the pair opened the Macdonald Sisters Studio at 128 Hope Street, Glasgow. Their innovative work was inspired by Celtic imagery, literature, symbolism, and folklore.[4] She later collaborated with her husband, the architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, whom she married on 22 August 1900.[5] Her most well-known works are the gesso panels made for interiors designed with Mackintosh, such as tearooms and private residences.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh is commonly recognized as Scotland's most famous architect, while Macdonald has been marginalised in comparison.[4] Yet Macdonald was celebrated in her time by many of her peers, including her husband who once wrote in a letter to Margaret "Remember, you are half if not three-quarters in all my architectural work ...";[6] and reportedly "Margaret has genius, I have only talent."[7]

Active and recognized during her career, between 1895 and 1924 she contributed to more than 40 European and American exhibitions.[4] Poor health cut short Margaret's career and, as far as is known, she produced no work after 1921.[8] She died in 1933, five years after her husband.

"The Glasgow Four" and Collaborative Work

It is unclear exactly when the Macdonald sisters met Mackintosh and his friend/colleague Herbert MacNair, but they probably met around 1892 at the Glasgow School of Art (Mackintosh and MacNair were studying as night students), introduced by the Headmaster Francis Newbery because he recognised that they were working in similar styles.[9] By 1894 they were showing their work together in student exhibitions, some of which was made collaboratively. Reception of the work was mixed, and it was commented that the gaunt, linear forms of the Macdonald sisters' artwork - clearly showing the influence of Aubrey Beardsley - were 'ghoulish' and earned them the moniker 'The Spook School'.[10] They became known locally as "The Four".[9]

Most collaborative work in the 1890s was with her sister, particularly following the opening of their studio in 1896. Some works were made by both together, while others were series of works, such as a set of four paintings with repoussé frames on the seasons where each two works on the theme. They also created a set of illustrations for William Morris' The Defense of Guinevere that was recently re-discovered in the special collections of the University at Buffalo.

She created several important interior schemes with Mackintosh. Many of these were executed at the early part of the twentieth century; and include the Rose Boudoir at the International Exhibition at Turin in 1903, the designs for House for an Art Lover in 1900, and the Willow Tea Rooms in 1902. She exhibited with Mackintosh at the 1900 Vienna Secession, where she was arguably an influence on the Secessionists Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann.

She and her husband also created botanical illustrations together.

Inspiration and style

Macdonald did not keep sketchbooks, which reflects her reliance on imagination rather than on nature.[11] A few sources provided significant inspiration for her works, including the Bible, the Odyssey, poems by Morris and Rossetti, and the works of Maurice Maeterlinck.[11] Her works, along with those works of her often collaborating sister, defied her contemporaries' conceptions of art. Gleeson White wrote, "With a delightfully innocent air these two sisters disclaim any attempt to acknowledge that Egyptian decoration has interested them specially. 'We have no basis.' Nor do they advance any theory."[11]

The beginning of Macdonald's artistic career reflects broad strokes of experimentation. Largely drawing from her imagination, she reinterpreted traditional themes, allegories, and symbols in inventive ways.[12] For instance, immediately following the 1896 opening of her Glasgow studio with her sister, she transformed broad ideas such as "Time" and "Summer" into highly stylized human forms.[13] Many of her works incorporate muted natural tones, elongated nude human forms, and a subtle interplay between geometric and natural motifs. Above all, her designs demonstrated a type of originality that distinguishes her from other artists of her time.[14]

Popular work

Her best-known works include the gesso panel The May Queen, which was made to partner Mackintosh's panel The Wassail for Miss Cranston's Ingram Street Tearooms, and Oh ye, all ye that walk in Willowood, which formed part of the decorative scheme for the Room de Luxe in the Willow Tearooms. All three of these are now on display in the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow. In 2008 her 1902 work The Red Rose and the White Rose was auctioned for 1.7 million UK pounds or $3.3 million.[15]

Gallery

Winter, 1898.

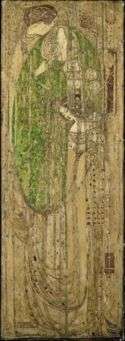

Winter, 1898. The May Queen, 1900.[16]

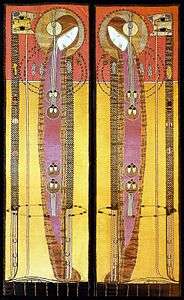

The May Queen, 1900.[16] Embroidered panels, 1902.

Embroidered panels, 1902. White Rose And Red Rose, 1902.

White Rose And Red Rose, 1902. Oh ye, all ye that walk in Willowood, 1903.

Oh ye, all ye that walk in Willowood, 1903. Opera Of The Winds, 1903.

Opera Of The Winds, 1903. Ophelia, 1908.

Ophelia, 1908._by_Margaret_Macdonald_Mackintosh.jpg) The Mysterious Garden, 1911.

The Mysterious Garden, 1911. The Opera of the Seas, 1915.

The Opera of the Seas, 1915. La mort parfumée, 1921.

La mort parfumée, 1921. Menu card design, 1911.

Menu card design, 1911. The Room de Luxe at the Willow Tea Rooms.

The Room de Luxe at the Willow Tea Rooms.

References

- ↑ Orme Girls' School, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Registers

- ↑ 1881 Census

- ↑ "The Mysterious Garden – Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh". National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Panther, Patricia. "Margaret MacDonald: the talented other half of Charles Rennie Mackintosh". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "MX.04 Interiors for 120 Mains Street" (PDF). Mackintosh Architecture : Context, Making and Meaning. University of Glasgos. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ The Chronicle: the letters of Charles Rennie Mackintosh to Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Pamela Robertson, ed.

- ↑ Kirkham, Pat (2001). Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century (Fourth ed.). United States of America: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 81.

- ↑ "Margaret Macdonald (1864–1933)". Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- 1 2 Howarth, Thomas (1990). "Introduction". In Burkhauser, Jude. 'Glasgow Girls': Women in Art and Design 1880–1920. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-84195-151-5.

- ↑ Burkhauser, Jude (1990). "The Glasgow Style". 'Glasgow Girls': Women in Art and Design 1880–1920. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84195-151-5.

- 1 2 3 Robertson, Pamela (1990). "Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1864–1933)". In Burkhauser, Jude. 'Glasgow Girls': Women in Art and Design 1880–1920. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-84195-151-5.

- ↑ Neat, Timothy (1990). "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor: Margaret Macdonald and the Principle of Choice". In Burkhauser, Jude. 'Glasgow Girls': Women in Art and Design 1880–1920. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-84195-151-5.

- ↑ Robertson, Pamela (1990). "Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1864–1933)". In Burkhauser, Jude. 'Glasgow Girls': Women in Art and Design 1880–1920. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-84195-151-5.

- ↑ Robertson, Pamela (1990). "Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1864–1933)". In Burkhauser, Jude. 'Glasgow Girls': Women in Art and Design 1880–1920. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-84195-151-5.

- ↑ "MARGARET MACDONALD MACKINTOSH THE WHITE ROSE AND THE RED ROSE, 1902". Christie's. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ Wikigallery - The May Queen 1900, by Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Margaret MacDonald. |

- Biography at the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society

- works by Margaret Macdonald in the Hunterian Art Gallery Collections

- Information on The Group of Four from the Hunterian Art Gallery