Martin Peerson

| Martin Peerson (or Pearson, Pierson) | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Between 1571 and 1573 probably March, Cambridgeshire, England |

| Died |

1650 or 1651 (aged 77–80); buried 16 January 1651 London, England |

| Genres | Classical music |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, organist and virginalist |

| Years active | Beginning of the 17th century |

Martin Peerson (or Pearson, Pierson) (born between 1571 and 1573; died December 1650 or January 1651 and buried 16 January 1651) was an English composer, organist and virginalist. Despite Roman Catholic leanings at a time when it was illegal not to subscribe to Church of England beliefs and practices, he was highly esteemed for his musical abilities and held posts at St Paul's Cathedral and, it is believed, Westminster Abbey. His output included both sacred and secular music in forms such as consort music, keyboard pieces, madrigals and motets.

Life and career

From Peerson's will and the March marriage registers, it appears that he was the son of Thomas and Margaret Peerson of March, Cambridgeshire, in England. It is believed that Martin Peerson was born in the town of March between 1571 and 1573, as records show that his parents married in 1570, but a "Margaret Peersonn" was married in 1573.[1] It therefore seems that Thomas Peerson died a few years after 1570 and that Martin's mother remarried.

In the 1580s, Peerson was a choirboy of St. Paul's Cathedral in London under organist Thomas Mulliner.[2] Subsequently, he came under the patronage of the poet Fulke Greville. On May Day in 1604 Peerson's setting of the madrigal See, O See, Who is Heere Come a Maying was performed as part of Ben Jonson's Private Entertainment of the King and Queene at the house of Sir William Cornwallis at Highgate (now in London). A letter dated 7 December 1609 states that at the time Peerson was living at Newington (now Stoke Newington, London) and had composed several lessons for the virginals, which was his principal instrument. It appears that he had Roman Catholic sympathies, for that year, on the same occasion as Jonson, he was convicted of recusancy – the statutory offence of not complying with the established Church of England.[1]

Peerson then took up musical studies at the University of Oxford. In order to do so, he would have had to subscribe to Protestantism. In 1613, he was conferred a Bachelor of Music (B.Mus.) and was appointed Master of the Boys of Canterbury Cathedral.[2] It is possible that he was the "Martin Pearson" who was sacrist at Westminster Abbey from 1623 to 1630. Between June 1624 and June 1625 he returned to St. Paul's Cathedral as almoner and Master of the Choristers; there is also some evidence suggesting he was later made a petty canon. Although all cathedral services ceased at the end of 1642 following the outbreak of the English Civil War, he retained the title of almoner and, along with the other petty canons and the vicars choral, had special financial provision made for him. Peerson is known to have been buried on 16 January 1651 in St. Faith's Chapel under St. Paul's.[1][3] He therefore died in either December 1650 or, more likely, January 1651.

In spite of his Roman Catholic leanings, evidenced by the use of pre-Reformation Latin texts for his motets and his 1606 conviction for recusancy, Peerson's position at the heart of the Anglican establishment confirms the overall esteem in which he was held.[4]

Music

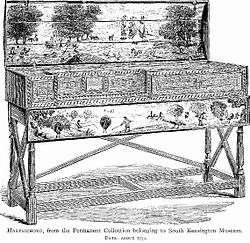

Peerson's powerful patrons enabled him to print and publish a considerable quantity of his music, although little remains today.[5] The only four extant keyboard pieces – "Alman", "The Fall of the Leafe", "Piper's Paven" and "The Primerose" – appear in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (c. 1609 – c. 1619), one of the most important sources of early keyboard music containing more than 300 pieces from the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods. He also set to music some of William Leighton's verses, written by the latter while in prison for debt. Together with works by other composers, these were published as The Teares and Lamentatacions of a Sorrowfull Soule in 1614. This was followed two years later by Tristiae Remedium, with texts assembled by the Reverend Thomas Myriell mainly using psalm texts in the English language.[6]

In 1620 Peerson's collection Private Musicke was published.[7] It contained secular music, including madrigals and consort songs, for one or two voices accompanied by viols or virginals. He published some metrical psalter tunes in Thomas Ravenscroft's 1621 work The Whole Booke of Psalmes with the Hymnes Evangelicall and Songs Spirituall, and then a group of Motets or Grave Chamber Musique in 1630 with English texts and the then-fashionable keyboard continuo;[8] the latter work contains two very fine songs of mourning.[2][6]

Thereafter, despite changing musical trends, Peerson's music showed significant roots in Renaissance polyphony. However, he was adept in the use of then-modern compositional procedures; this is evident in his often daring use of chromaticism, especially seen in word painting.[6] Some of his finest music is contained in his set of 15 Latin motets, which was probably composed around the turn of the century.[1] Existing only in a single copy, it originally consisted of five part-books but the Cantus book is lost. Richard Rastall, professor of historical musicology at the University of Leeds, spent 12 years reconstructing the missing part. The complete Latin motets have been published by Antico Edition, and a recording of their performance by Ex Cathedra entitled Peerson: Latin Motets was produced by Hyperion Records in 2005.[4][9]

Selected works

- Private Musicke. Or the First Booke of Ayres and Dialogues: Contayning Songs of 4. 5. and 6. Parts, of Seuerall Sorts, and being Verse and Chorus, is Fit for Voyces and Viols. And for Want of Viols, they may be Performed to either the Virginall or Lute, where the Proficient can Play vpon the Ground, or for a Shift to the Base Viol alone. All Made and Composed According to the Rules of Art. By M. P. Batchelar of Musicke, London: Printed by Thomas Snodham, 1620, OCLC 606486968.

- Mottects or Grave Chamber Mvsiqve: Containing Songs of Fiue Parts of Seuerall Sorts, some ful, and some Verse and Chorus. But all Fit for Voyces and Vials, with an Organ Part; which for want of Organs, may be Performed on Virginals, Base-Lute, Bandora, or Irish Harpe. Also, A Mourning Song of Sixe Parts for the Death of the late Right Honorable Sir Fvlke Grevil ... Composed According to the Rules of Art by M.P., London: Printed by William Stansby, 1630, OCLC 496804311.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Audrey Jones; Richard Rastall, "Peerson [Pearson], Martin", in L. Macy, ed., Grove Music Online, retrieved 8 April 2007, (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 Martin Peerson (1572–1650) (fl. end 15th Century), Here of a Sunday Morning, archived from the original on 7 May 2013, retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ↑ There is no extant memorial to Peerson in St. Paul's Cathedral. The Cathedral was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666 and subsequent demolition effaced most evidence on the ground of pre-Fire burials; Peerson's is not among the few remaining fragments of monuments: personal e-mail communication on 11 May 2007 with Joseph Wisdom, Librarian of St. Paul's Cathedral Library.

- 1 2 Recordings: Peerson: Latin Motets, Ex Cathedra, 2005, archived from the original on 7 October 2007.

- ↑ MARTIN PEERSON (c. 1572–1651): Latin Motets, Hyperion Records, 2005, archived from the original on 2 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 Gary Higginson (March 2005), Review of Ex Cathedra's recording Peerson: Latin Motets (2005), Musicweb International, archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- ↑ M[artin] P[eerson] (1620), Private Musicke. Or the First Booke of Ayres and Dialogues: Contayning Songs of 4. 5. and 6. Parts, of Seuerall Sorts, and being Verse and Chorus, is Fit for Voyces and Viols. And for Want of Viols, they may be Performed to either the Virginall or Lute, where the Proficient can Play vpon the Ground, or for a Shift to the Base Viol alone. All Made and Composed According to the Rules of Art. By M. P. Batchelar of Musicke, London: Printed by Thomas Snodham, OCLC 606486968.

- ↑ M[artin] P[eerson] (1630), Mottects or Grave Chamber Mvsiqve: Containing Songs of Fiue Parts of Seuerall Sorts, some ful, and some Verse and Chorus. But all Fit for Voyces and Vials, with an Organ Part; which for want of Organs, may be Performed on Virginals, Base-Lute, Bandora, or Irish Harpe. Also, A Mourning Song of Sixe Parts for the Death of the late Right Honorable Sir Fvlke Grevil ... Composed According to the Rules of Art by M.P., London: Printed by William Stansby, OCLC 496804311.

- ↑ "Settling an Old Score", The Reporter: The University of Leeds Newsletter (509), 4 July 2005, archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

References

- Higginson, Gary (March 2005), Review of Ex Cathedra's recording Peerson: Latin Motets (2005), Musicweb International, archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- "Settling an Old Score", The Reporter: The University of Leeds Newsletter (509), 4 July 2005, archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

Further reading

- Husk, William H. (1900), "PEERSON, PEARSON, or PIERSON, MARTIN", in Grove, George, A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1889) by Eminent Writers, English and Foreign. With Illustrations and Woodcuts., 2, London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., p. 683, OCLC 861060.

- Heydon, Julia Jeanne (1990), Martin Peerson's Private Musicke: A Transcription, Edition, and Study of an Early 17th-century Collection of English Consort Songs [unpublished D.M.A. thesis], Eugene, Or.: University of Oregon, OCLC 24253447.

- Jones, Audrey (1957), The Life and Works of Martin Peerson [unpublished M.Litt. thesis], Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge, OCLC 21422375.

- Middleton, Louisa M. (1895), "PEERSON, PIERSON, or PEARSON, MARTIN (1590?–1651?)", in Lee, Sidney, The Dictionary of National Biography: From the Earliest Times to 1900, 44, London: Elder Smith & Co., pp. 232–233, OCLC 163196182.

- Peerson, Martin ([2001?]–), Rastall, Richard, ed., Complete Works, Newton Abbot, Devon, England: Antico Edition, OCLC 55506888. 2 vols.

External links

- Free scores by Martin Peerson in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Martin Peerson at the International Music Score Library Project

- The Peerson Project by the University of Leeds